After an (unfortunately still) underappreciated run in Batman and Detective Comics in the mid-1980s, Doug Moench took a break for about five years before returning to Gotham City with a new attitude. If his earlier work had an emphasis on grounded action and characterization, filtered through a literary sensibility, Moench now chose to forgo most attempts at realism, instead engaging with the Dark Knight’s world as if it was an outlandish caricature.

His eccentric approach was all the more remarkable because Doug Moench ended up playing a central role in defining the feel of modern Batman comics. Besides a lengthy run on Batman (1992-1998), he went on to write several neat story-arcs for Legends of the Dark Knight as well as a pretty awful Catwoman run, not to mention a bunch of specials and short stories in anthologies like Showcase, Batman Chronicles, and Batman 80-Page Giant.

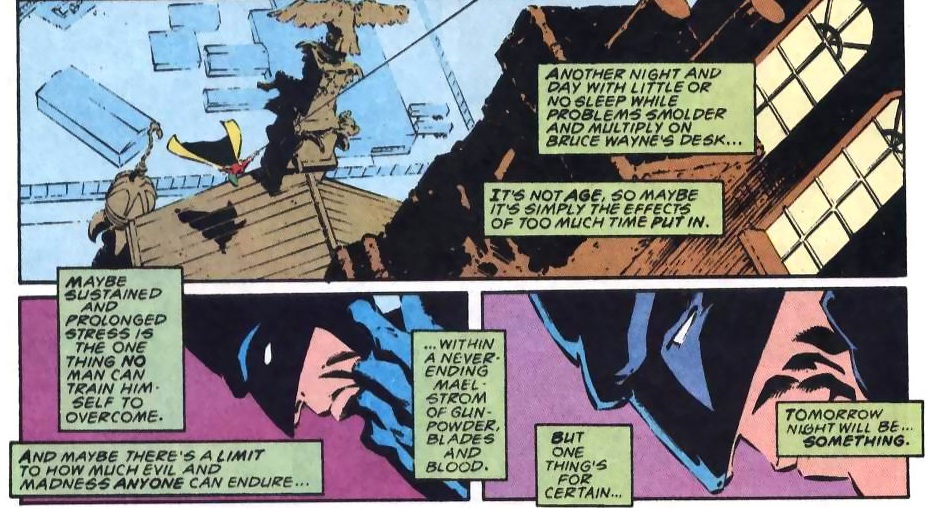

When people associate the 1990s with a brooding, über-grim Batman, this is largely a result of Moench’s purple prose…

Batman #485

Batman #485

Such a way of writing Batman is often seen as an editorially-mandated, post-Dark Knight Returns trend (and surely there is some truth to that), but it should also be seen in the context of Doug Moench’s evolution into full-on operatic mode.

Seriously, it’s like Moench read Rorschach’s diaries and felt like they were not gritty enough…

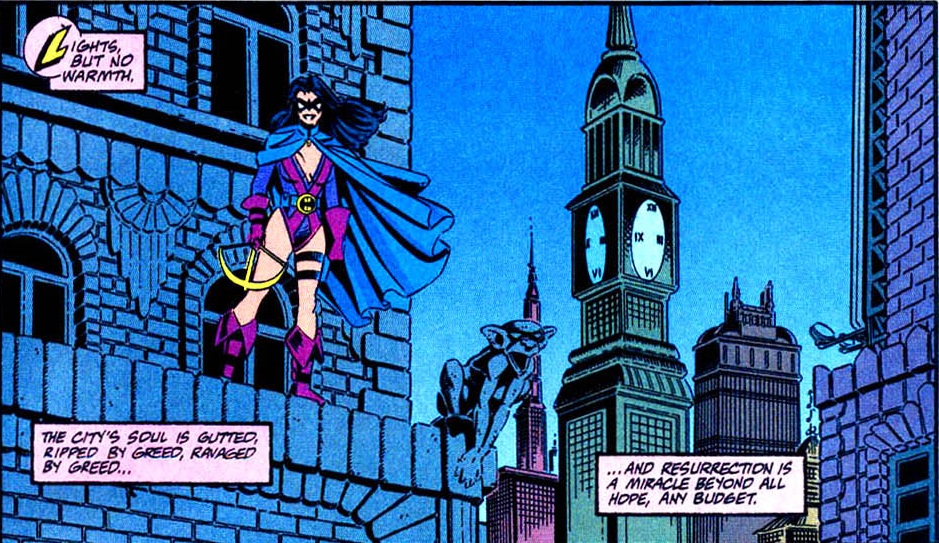

Showcase ’93 #9

Showcase ’93 #9

At first, when Moench returned to the Gotham corner of the DCU as a regular writer, his take on it didn’t come across as strikingly different from what he had done before… He seemed to be picking up where he left off, bringing back characters created during his former run – such as Circe and Harvey Bullock – and doing callbacks to his tales about Black Mask (in Batman #484) and the Dark Rider (in Batman #515), as well as to Gerry Conway’s original Killer Croc storyline (in Batman #489), thus establishing them as part of post-Crisis continuity.

It didn’t take long before we got some glimpses of the high-octane madness to come, though. You could see Doug Moench absorbing the genre’s turn towards darkness, especially as he became one of the main writers of 1992’s ‘Knightfall’ story-arc, in which he explored Bruce Wayne’s psychological and physical breakdown. Moench also helped shape Bruce’s temporary successor, the demented Jean-Paul Valley (aka AzBats), who looked and acted quite differently from the regular Batman yet drew from the same dark well:

Batman #500

Batman #500

That said, it was after the ‘Knightfall’ and ‘Prodigal’ crossovers that Doug Moench’s characterization became really over-the-top. Most of the cast began to talk and act in preposterously exaggerated ways, striking shameless dramatic poses and uttering ill-disguised exposition, as if consciously owning up to the fact that they were comic book heroes and villains.

Not by accident, this shift coincided with the time when Kelley Jones became the regular artist on Batman, in late 1994. Jones’ pencils – savagely inked by John Beatty – are themselves as outrageously over-the-top as you can get, adorning the Dark Knight with some of the most bewildering, goddamned gothic capes and shadows ever to grace mainstream comics:

Batman #516

Batman #516

Batman #530

Batman #530

Doug Moench clearly decided to write for Kelley Jones’ strengths and he just swung for the fences. Moench’s scripts filled the series with freakish monsters and big, bodacious violence while giving Jones the chance to draw, in his own inimitable style, classic horror-inspired characters like the demon Etrigan, the Spectre, Man-Bat, Deadman, and Swamp Thing:

Batman #522

Batman #522

(Yes, that’s Killer Croc making a killer pun.)

Outright embracing Kelley Jones’ cartoony neo-gothic vibe, Doug Moench soaked Batman’s stories in squirm-inducing ghoulish murders and dismembered body parts. On top of confrontations with most of the typical rogues gallery, the Dynamic Duo chased sick new villains who desecrated corpses and ripped people’s faces off, right there on the page!

In Moench’s defense, that kind of thing was not too unusual in the bat-books of the time… On an average month, you could easily find yourself starring at graphic depictions of a guy getting drilled alive, or being burned to a crisp, or getting his hands sawed off (or all of the above, in the case of Catwoman/Wildcat #4).

Likewise, in terms of overarching narrative, the Moench/Jones/Beatty run was immersed in its larger family of titles. Although most stories were self-contained, there was tight continuity between the bat-books in the form of background subplots that carried over from book to book and then paid off in occasional crossovers which wrapped the various series into the same meta-narrative – like in the cool ‘Contagion’ arc, where a dangerous virus outbreak in Gotham City brought together the casts of Batman, Detective Comics, Robin, Shadow of the Bat, Catwoman, and Azrael (there was also a Batman Chronicles tie-in, which launched Hitman).

None of this changes the fact that Doug Moench’s issues had quite a distinct voice. And while the tales illustrated by Kelley Jones were the ones where Moench went further over the edge, there were other fascinating collaborations. In particular, he did a number of comics with J.H. Williams III who, already at the time, enjoyed weaving intricate conceptual patterns into the layouts:

Batman Annual #21

Batman Annual #21

Kelley Jones’ and J.H. Williams III’s flair for decorating the borders of pages with thematic details was an obvious fit for Doug Moench who – as I’ve mentioned time and time again in this blog – has a thing for bountiful symbolism, a trait that definitely did not go away in the nineties… See, for example, how when Moench updated the origin of Jonathan Crane, the Scarecrow (in Batman Annual #19), he appeared to have squeezed in every single symbol, play on words, and intertextual reference to fear and scarecrows (and to Jonathan Crane’s name) he could find!

Even better: check out ‘Heat’ (Legends of the Dark Knight #46-49), in which there is a heat wave, a serial killer going after hot women, and racial tension heating up (due to the suspicion that the killer may be African-American, leading the authorities and white supremacist skinheads to persecute the black community, almost ushering in a riot). Plus, Catwoman is basically in heat, heavily hitting on Batman. And Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot is totally playing on television. And – I kid you not – the comic is drawn by Russ Heath! Seriously, given the racial theme, all that’s missing is a reference to the (awesome) film In the Heat of the Night…

Sure, these may not be the most interesting genre comics to deal with racism, but I just love Moench’s commitment. To cap things off, the threat of a violent clash is resolved literally and symbolically with a break in the heat (introduced through another irresistible pun):

Legends of the Dark Knight #49

Legends of the Dark Knight #49

Doug Moench also touched on the issue of race in ‘Suit of Evil Souls/The Greatest Evil’ (Batman #551-552), where the Caped Crusader teamed up with Ragman to fight the antisemitic gang Aryan Reich. What’s more, in ‘Ballistic’ (Batman Annual #17) – part of the lame ‘Bloodlines’ crossover (the one about alien vampires) – Moench tried to establish an enduring Asian-American hero through Kelvin Mao, a cop-turned-gun-toting-mutant-mercenary with the most ‘90s look and attitude you can imagine… Moench brought Ballistic back a couple of times, but it didn’t help that the stories were as uninspired as the character himself (even though, at one point, he did fight a post-punk version of the Three Stooges).

Speaking of politics, it was not uncommon for Moench’s characters to launch into political discussions, whether about Gotham’s fictional mayoral race (Batman #523) or about the actual post-Soviet world order (Batman #515). Above all, Moench kept returning to the topic of shadowy government operations and conspiracies.

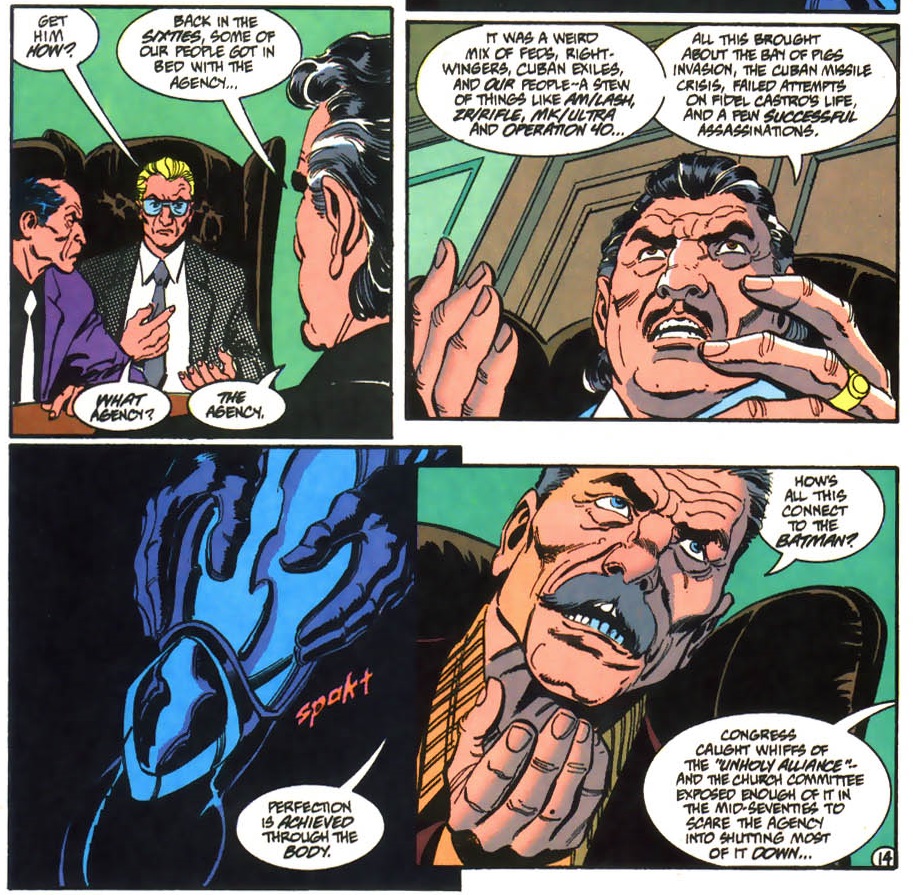

Batman #501

Batman #501

(The above excerpt is from a story in which mobsters hire Mekros – a mercenary who uses CIA techniques to brainwash himself – in order to get Batman. The CIA then sends its own corrupt assassin after Mekros, creating a free-for-all of action and double-crosses.)

More than a go-to narrative trick – like Grant Morrison’s nanotech or Denny O’Neil’s animal cruelty – this topic seemed to truly fascinate Doug Moench, who never missed a chance to feed our sense of paranoia, more often than not by reminding readers that the government can’t be trusted. (He also wrote, for Paradox Press, the anthologies The Big Book of Conspiracies and The Big Book of the Unexplained.)

I suppose this tendency reached its apogee in ‘Conspiracy’ (Legends of the Dark Knight #86-88), where Moench knit a kaleidoscopic tale of satanic rituals, political assassinations, bikers, serial killers, the Mob, the LAPD, Hollywood, the CIA, new agers, secret societies, and whatever else is missing from your conspiracy theory scorecard. By the end, the story implied that even Batman’s existence could be part of the cabal… (It’s a nifty arc, later collected in a DC Comics Presents one-shot. The art by J.H. Williams III, Mick Gray, and Dan Brown nails the eerie mood one associates with the sinister cults of Los Angeles, later mined by the comic series Fatale and the film Starry Eyes.)

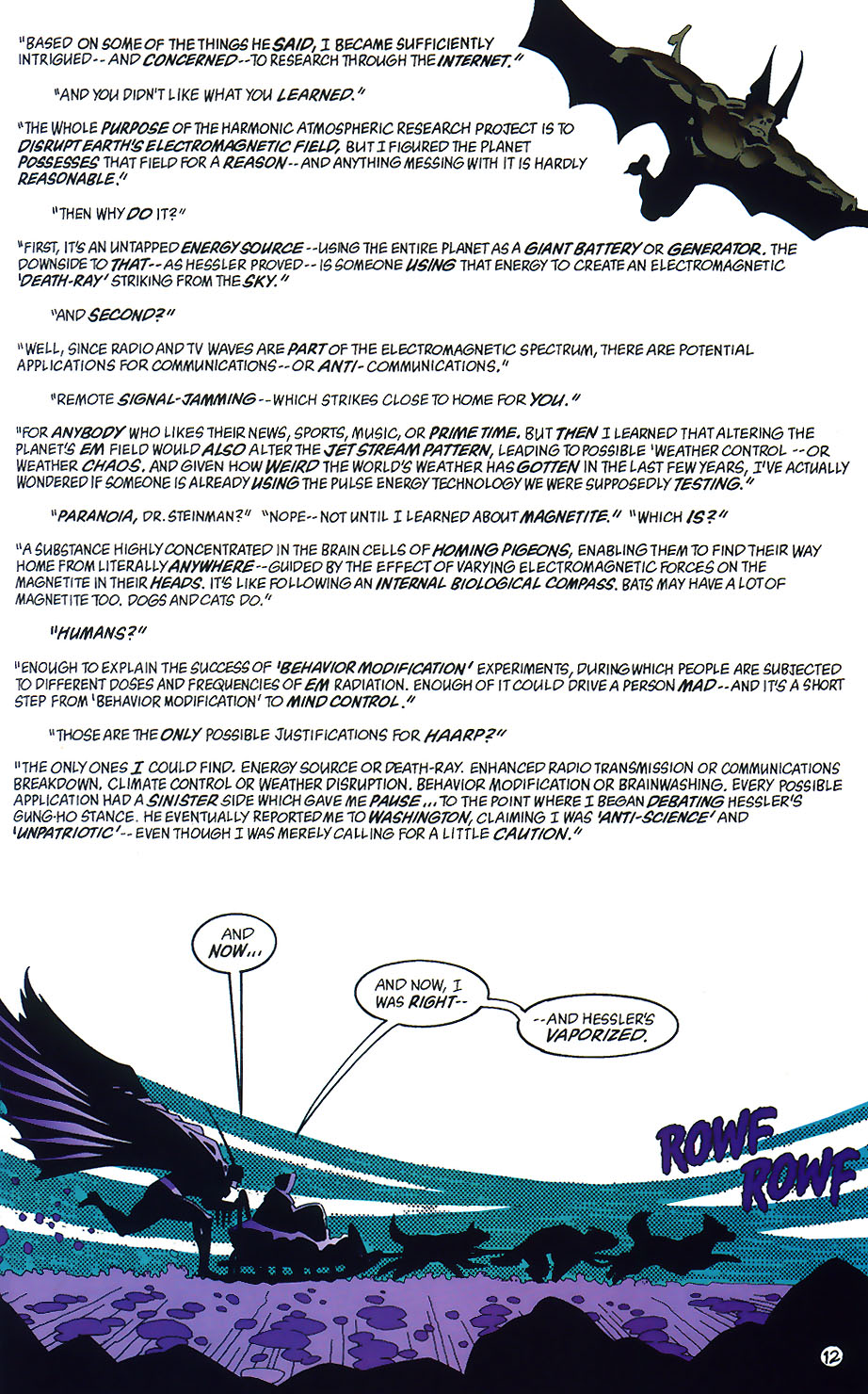

Another memorable instance of a plot revolving around covert operations took place in Batman 536-538. Man-Bat crashes into a secret program run by the US government in the Arctic, where scientists are bouncing harmonics off the upper atmosphere in order to weaponize ‘pulse energy.’ Washington sends in a team of shady troubleshooters to kill Man-Bat and it’s up to the Caped Crusader to both save the monster’s life and put an end to the dealings of the real monsters, i.e. the unethical HAARP (Harmonic Atmospheric Research Project). Moench gets so worked up with conspiracy theories that at one point he even forgets this is supposed to be a comic book:

Batman #538

Batman #538

Interestingly, after having pushed the Dark Knight to an almost abstract extreme, in the second half of this run Moench tried to humanize him once again by devoting more attention to Bruce Wayne. We see Bruce trying to get more involved in the Wayne Foundation, which leads to a hilarious scene in Batman #541 in which he shows up in the building unannounced and causes a panic because everyone assumes there is about to be a hostile takeover.

Moreover, Doug Moench gave Bruce Wayne a love interest in the form of radio host Vesper Fairchild:

Batman #540

Batman #540

The later issues do a fine job of turning Vesper Fairchild into a likable addition to the cast and giving some weight to her romance with Bruce Wayne (although, as usual, the writers who came afterwards had her brutally murdered).

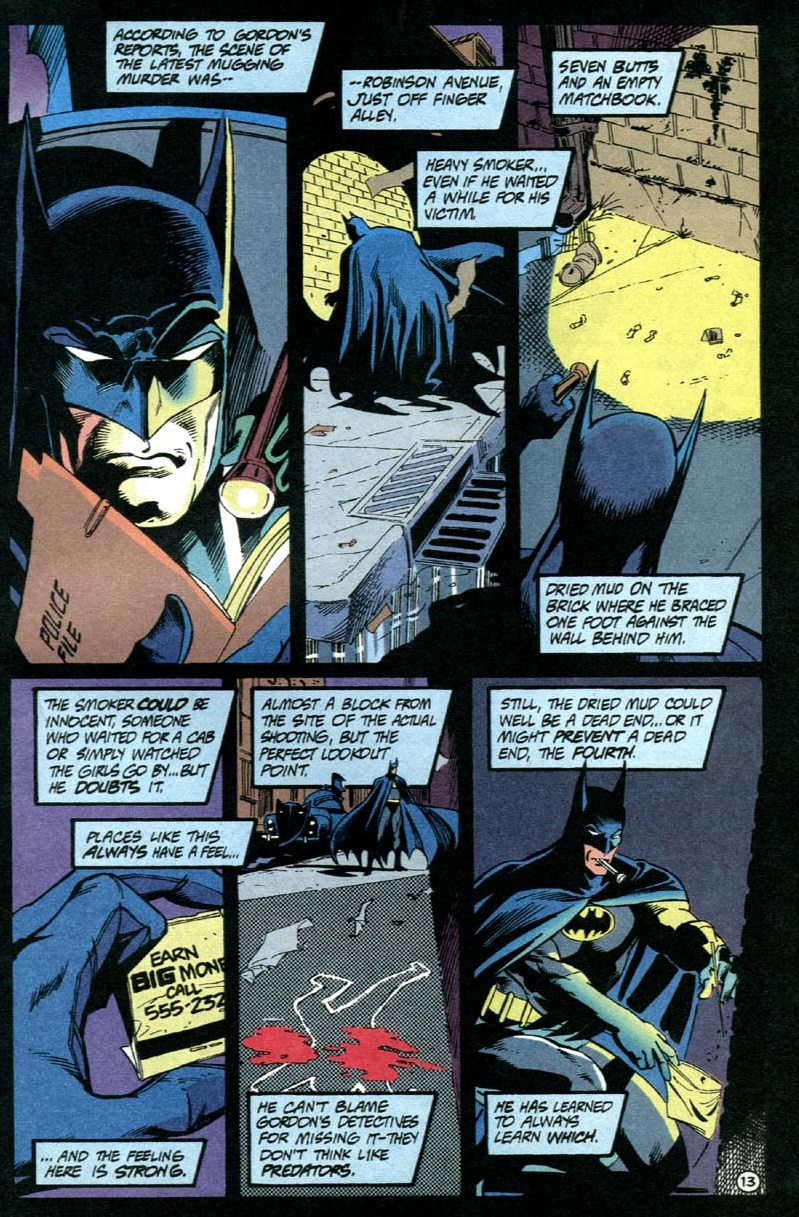

In fact, in case it is not clear already, perhaps I should stress that, despite all the baroque trappings, Doug Moench’s ‘90s output is not exactly shallow. It still includes quite a few relatively grounded stories and character moments (particularly among the contributions to Legends of the Dark Knight). And although gleefully geared towards throat-grabbing horror and superhero adventure, the main Batman title did not ignore the detective side of the Caped Crusader…

Batman #00

Batman #00

At the end of the day, the truth is that the division between Doug Moench’s ‘80s and post-‘80s phases is not entirely linear. For one thing, Moench was certainly no stranger to wild spectacle in the eighties, having also indulged in the era’s brand of delirious macho excess later spoofed by the likes of Sexcastle and Kung Fury. (Most notably, he wrote the sci-fi mini-series Slash Maraud, which features futuristic dinosaurs, alien despots, biker amazons, a cult devoted to classic horror movies, and a humanoid bear who at one point fights a gang of Nazis.)

Yet Moench’s post-eighties evolution is hard to deny, as he has taken Batman comics into darker and darker places over the years. The ultimate example of this is probably the handful of one-shots and mini-series he has produced with Kelley Jones, putting Burtonian spins on the Gotham cast (including, famously, one in which Batman battles Dracula).

I gotta admit, most of Moench’s ’90s run struck me as a poor man’s Vertigo (and to this day I chiefly associate Kelley Jones with Season of Mists). It felt rather obvious he’d used up most of his good ideas in the ’80s, and what was left was more often than not an embarrassing concoction of hidebound plotting, tin-eared dialogue, and left-wing anviliciousness.

That said, there were more than a few diamonds in the rough (Batman #520 remains a favorite of mine, and perhaps the apex of Moench’s Bullock), and I’ve long had a soft spot for Moench’s Penugin, particularly because the good Mr. Cobblepot plays *precisely* to his strengths as well as flaws…