Something I would like to do more this year is to write about Eurocomics – especially the old Franco-Belgian bande dessinée albums that were such a huge part of my childhood. Today, let’s have a closer look at just a few of the various layers we can find in Hergé’s seminal series The Adventures of Tintin, about the globetrotting escapades of the titular young reporter and his dog, Snowy (‘Milou’ in the original).

This series was originally published between 1929 and 1976, so naturally there is a striking evolution throughout. I cannot wholeheartedly recommend the first stories (the anti-communist Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the colonialist Tintin in the Congo, and the anti-American Tintin in America) except for completists – even setting aside the ultra-reactionary politics (which apparently matched the tone of the Belgian catholic newspaper that originally published the comic), the artwork and plotting are pretty crude. Hergé was still finding his feet through fairly simple gag-driven narratives. To be fair, though, each of these already feels like a giant leap in quality compared to its predecessor and you can certainly discern some inventive uses of the medium among the goofy comedy and cringeworthy stereotypes – especially in Tintin in America, which comes off like a madcap, surreal mash-up of caricatures about the United States taken from westerns and gangster pictures.

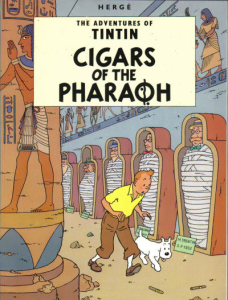

It was with the fourth installment, Cigars of the Pharaoh (initially published in 1932-1934), that Hergé first nailed the ‘rollicking mystery’ style that would become the series’ core identity. The art was sharper (although the collected versions I read were partially redrawn by Hergé later on, so it’s hard to measure how much sharper) and the plot more elaborate (if not without some contrived coincidences), but not at the expense of any entertainment value – if anything, Cigars feels even more like a thrilling serial, as Tintin starts out by exploring an Egyptian tomb and ends up in the throes of an international drug-smuggling ring that stretches all the way to India… Along the way, he finds himself lost at sea, alone in the desert, buried alive, attacked by a tiger, and hypnotized by an evil fakir (plus, he spends some time living in the jungle, where – in a delightfully bizarre sequence – he learns how to communicate with elephants).

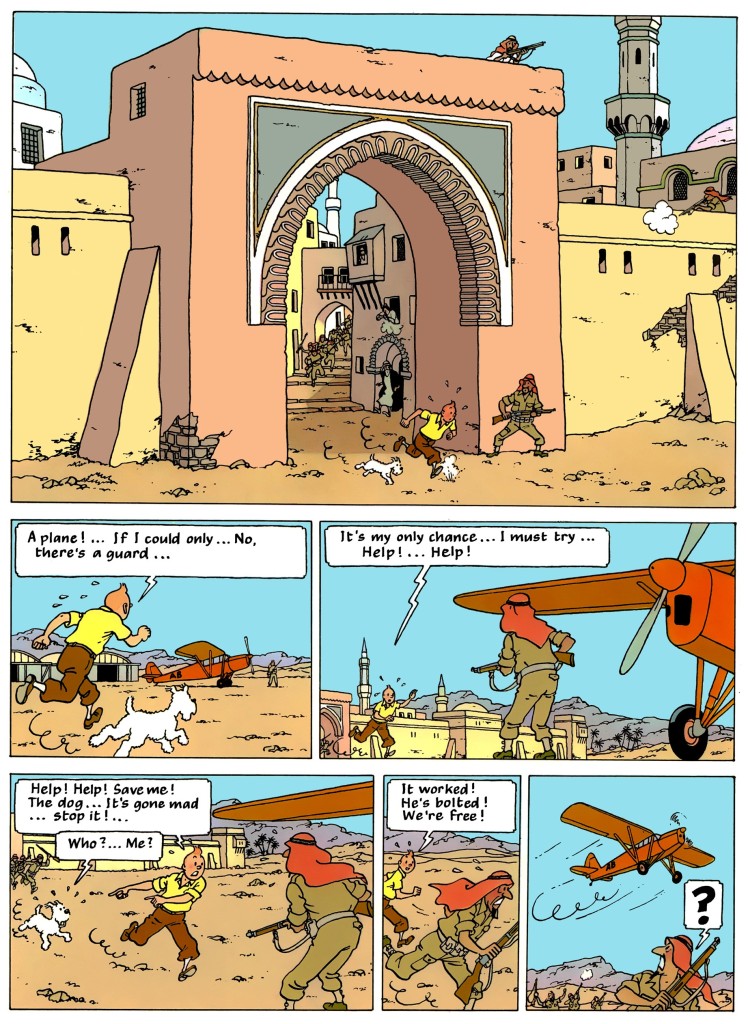

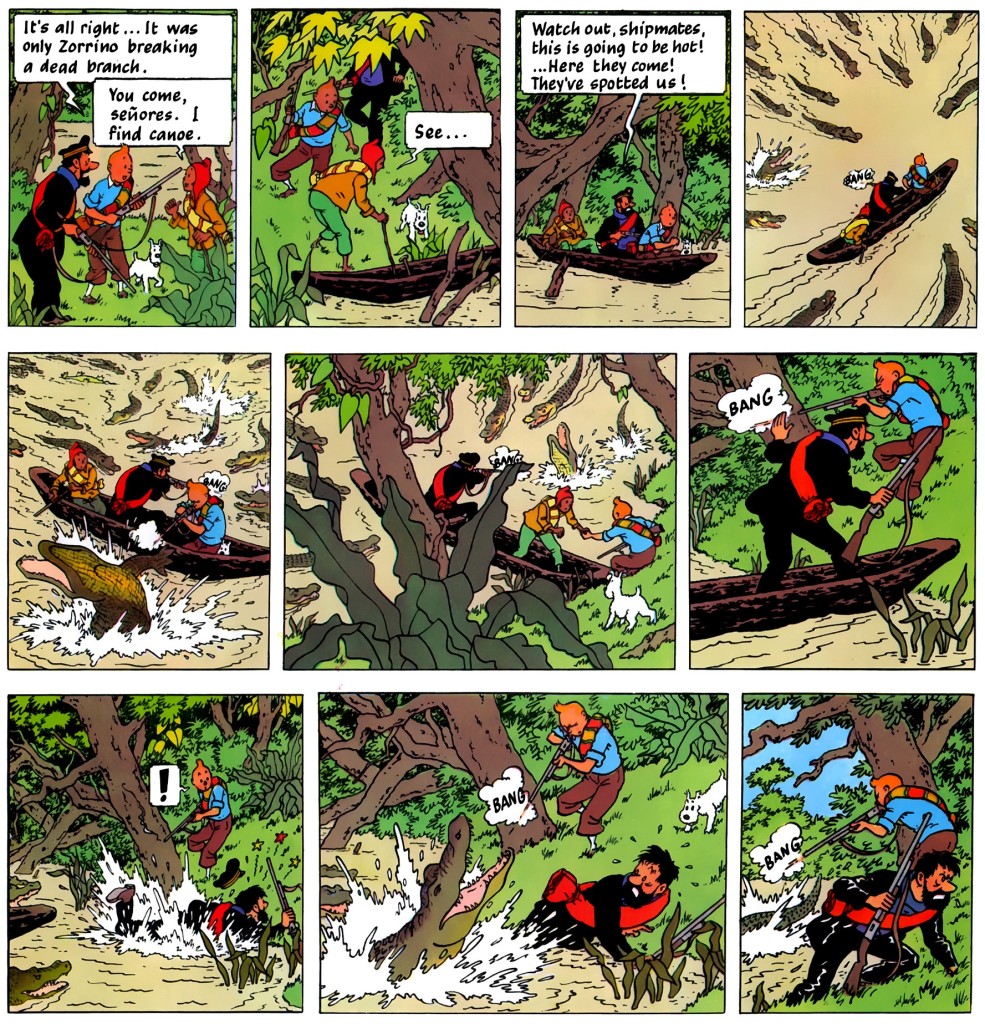

There are also chases and gunfights galore…

Cigars of the Pharaoh

Cigars of the Pharaoh

(Notice how the larger page size of European comics allows Hergé to get away with an impressive splash and still cram plenty of twists onto the bottom of the page…)

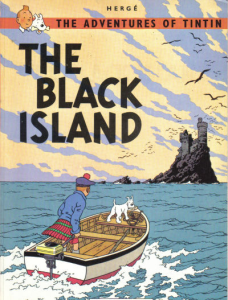

The sequel, The Blue Lotus, was an even more ambitious Boy’s Own adventure, as Tintin and Snowy faced the remainders of the last story’s drug-smuggling ring, only to find themselves caught in the middle of the Japanese occupation of China. The Broken Ear then took them to a Latin America embroiled in revolution. By the time we get to The Black Island (set in the UK) and King Ottokar’s Sceptre (set in a fictitious kingdom in the Balkans), we find Hergé in full command of the medium, having overcome an earlier tendency for wordy dialogue and now striking a reader-friendly balance between words and pictures. His style became so seamless as to appear misleadingly simple, to the point where it is easy to dismiss or underestimate all the craft in display, but you really shouldn’t do so.

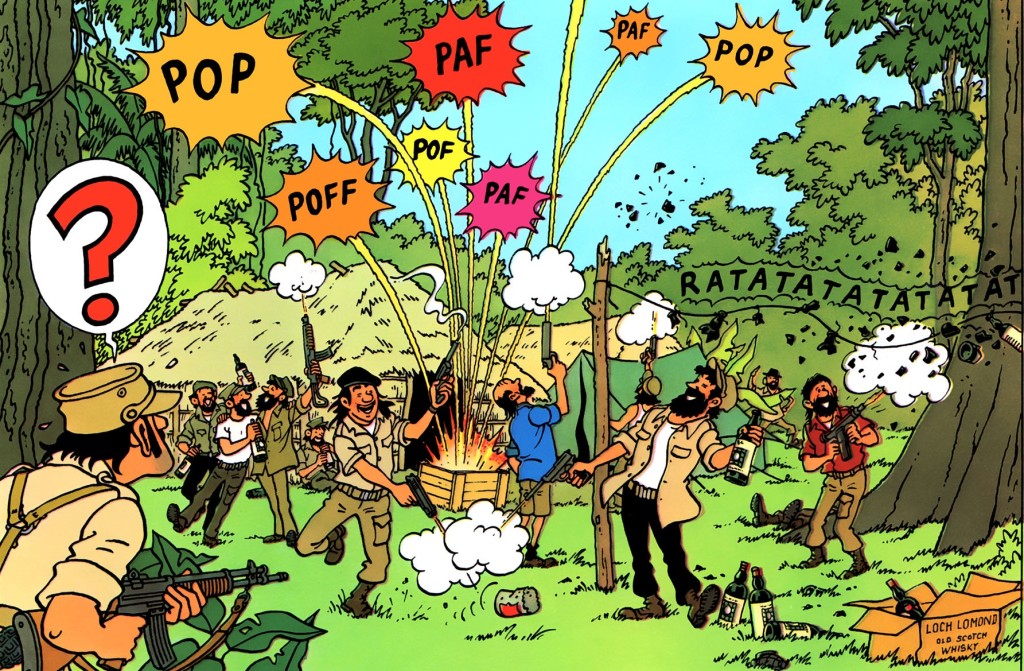

In 1938, when Action Comics #1 blew up the horizon of, well, action comics in the US, the European version seemed like it already was miles (or, rather, kilometers) further down the road in terms of narrative sophistication, not to mention pure kinetic power. By the time we get to The Crab with the Golden Claws, we find an Hergé successfully exploring the potential of splashes to elevate action beats, having already developed other formal techniques, including the ability to mine sudden ellipses for both pacing and humor…

The Crab with the Golden Claws

The Crab with the Golden Claws

(Tintin doesn’t look like an alpha male at all, but the series keeps suggesting that he is a badass brawler, as well as pretty comfortable handling a gun…)

Hergé’s incredible pace is arguably the main reason to read these books, as Tintin himself can be a relatively bland – if likable – hero most of the time. Without a trace of cynicism about the press, he’s a journalist who never seems all that keen to write or publish – his investigations are driven by curiosity and by a committed sense of justice, but he could just as easily have been a scholar or a detective instead. His strong determination and altruism reflect an age of ‘undeconstructed’ archetypes, especially when it comes to fiction aimed at younger audiences, which is bound to feel too naive for some modern readers (then again, they may find it refreshing). Tintin’s uncomplicated feelings are probably also a byproduct of the fact that the whole thing is plot-driven, with little patience for psychological drama.

Still, we do occasionally get some interesting characterization of other cast members, most notably of the flawed Captain Haddock – a bigoted, short-tempered alcoholic who becomes Tintin’s closest (human) friend. With his rough ways, Haddock can serve as equal parts sidekick, emotional id, and comic relief.

Prisoners of the Sun

Prisoners of the Sun

The continuity becomes more intricate starting with The Secret of the Unicorn, including a few two-parter albums and plenty of callbacks to earlier tales, weaving an expanding web of cameos and story connections. This is not to say that there is any lack of accessibility or instant gratification when you read each individual volume, especially as they dabble in different subgenres: The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun are my platonic ideal of an old-school explorer’s fantasy, Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon are hardcore sci-fi, The Calculus Affair is a Cold War spy yarn, The Castafiore Emerald is a screwball parody of Agatha Christie’s whodunnits, Tintin and the Picaros is a political thriller.

And yet, the series as a whole feels remarkably consistent. For one thing, this is one of those comics where, even though the world outside changes in real time, the characters’ ages seem perpetually frozen, so they sound comfortingly familiar throughout the decades. Moreover, there are a number of running themes linking even the most disparate tales, such as heroism, compassion, exploration, and geopolitical games (usually run by selfish individuals who don’t care about the masses).

And alcohol.

Tintin and the Picaros

Tintin and the Picaros

(Alcohol is a recurring source of humor, drama, and characterization, culminating in Tintin and the Picaros, where it plays a key role in the plot.)

The consistency is also secured by Hergé’s rock-solid visuals. The well-delineated drawing style he perfected, known as ‘clear line’ (ligne claire), has come to be associared with serious, contemplative comics like Jason Lutes’ Berlin, Rutu Modan’s The Property, or Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina. In Tintin, however, it was commitedly put in the service of full-on comedy and adventure.

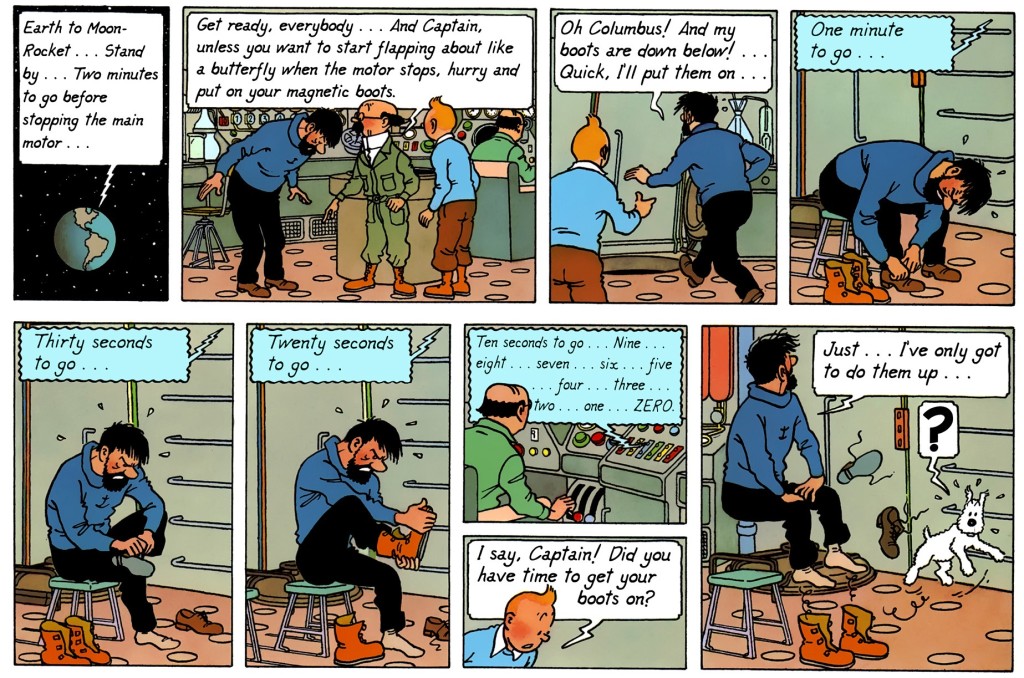

Explorers on the Moon

Explorers on the Moon

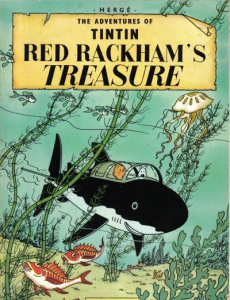

Almost every page finishes on a cliffhanger, pushing you into the next one, and there is zero padding along the way (unless you consider the comedic bits filler, which I don’t). Despite the average of four rows of panels per page, the stories hardly ever slow down, as exposition gets typically intermingled with either breathtaking action or slapstick gags. The Secret of the Unicorn, for instance, features a 13-page tour-de-force that consists of little more than Haddock telling a pirate tale yet nevertheless manages to be visually gripping (the sequel, Red Rackham’s Treasure, then gives us a properly extended seafaring yarn). The result is almost cinematic in the way it creates rhythm through parallel montage and constant movement.

Between this and the fact that the stories often playfully feature doubles, conspiracies, and a wrongfully accused protagonist on the run, the tone seems very close to the films of Alfred Hitchcock (whose career spans pretty much the same decades). Not that Hergé was necessarily following Hitchcock’s work or vice versa, but they probably drew inspiration from the same type of sources, which explains the profusion of similar set pieces in 1930s’ Tintin and in Hitch’s The 39 Steps, Sabotage, Young and Innocent, and, especially, The Lady Vanishes and Foreign Correspondent (except that Hergé was much less interested in romantic subplots… or in gutsy female characters, for that matter). Hell, it’s the same sort of material that would inform Hollywood’s World War II propaganda thrillers just a few years later, although Tintin’s relationship with WWII turned out to be quite different…

On top of the series’ conservative origins and ethnic stereotyping, some critics have charged Hergé with collaborationism due to the fact he continued to work for the establishment throughout the Nazi occupation of Belgium. It’s one of the things that makes Tintin’s 10th book – the apocalyptic The Shooting Star – so fascinating.

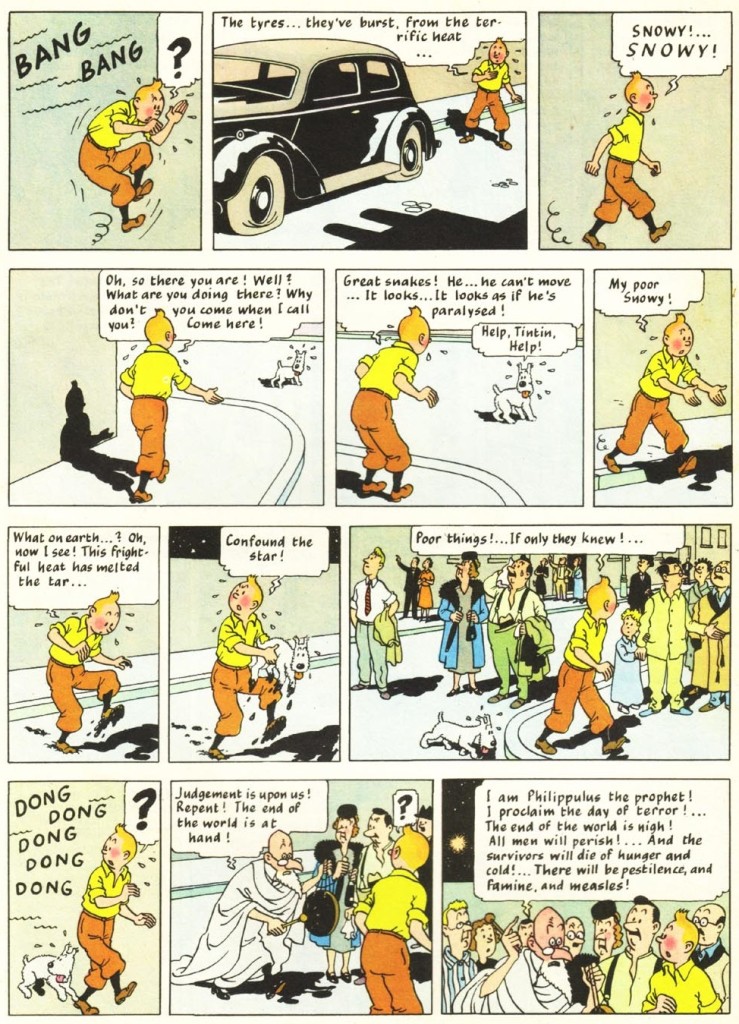

The Shooting Star

The Shooting Star

On the surface, The Shooting Star resembles escapist science fiction, as Tintin goes on a naval expedition to retrieve a fallen meteor (one of several stories that owe a clear debt – direct or indirect – to Jules Verne), culminating in a climax that anticipates the monster movies of the 1950s. However, once you take into account that the tale was first serialized in 1941-1942, you start spotting a more sinister subtext… It’s not just that Tintin’s expedition is made up of scientists from Axis, occupied, and neutral countries – it’s that their evil rivals sound Anglo-Saxon and are led by a large-nosed banker who conspires against them in the name of profit (and apparently there were other antisemitic caricatures in the original, which didn’t make it to the collected edition). Still, it’ s worth noting that if you set aside your outside knowledge about WWII and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (in other words, if you read the book like I first did, as a kid), it does work as a moral fable, one where the heroes are willing to forego victory in order to help a stranger in need and where the villains are the ones prone to cheating and endangering others to get what they want.

All this brings us to the unavoidable subject of Tintin’s racist undertones, which I’ll be discussing next week, when I’ll delve deeper into the series’ politics…