In the early 1970s, the Unknown Soldier feature of Star Spangled War Stories told exciting spy adventures set in World War II, starring a disfigured operative turned master-of-disguise who undertook secret missions under direct orders from Washington. As I explained last week, that series was not without a certain degree of grittiness. However, when the team of editor Joe Orlando, writer David Michelinie, and artist Gerry Talaoc took over, in issue #183 (cover-dated November-December 1974), they raised the bar to another level.

The new guys infused The Unknown Soldier with a no-holds-barred, take-no-hostages attitude. A more accurate way to put it is that they finally engaged with the increasing tension between the series’ premise and the current zeitgeist, embracing the skepticism of authority in general and militarism in particular ushered in by the Watergate scandal and the tail end of the Vietnam War.

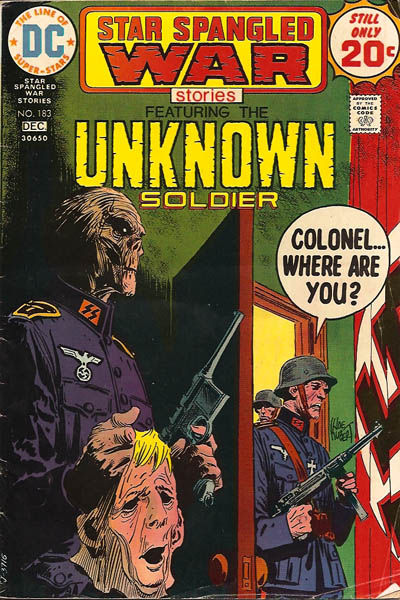

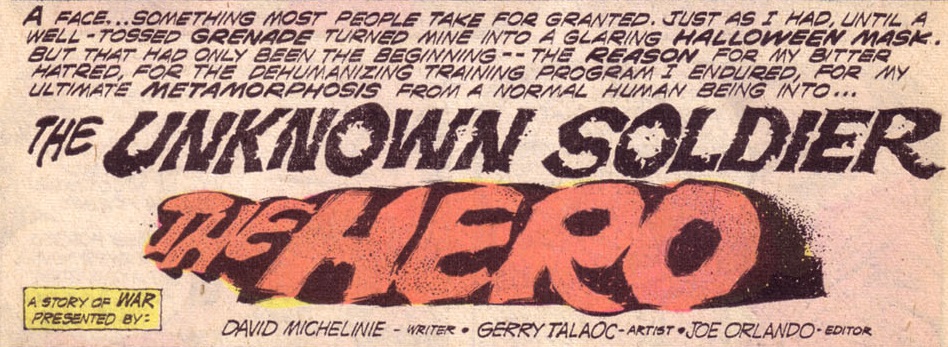

Let’s start with the most obvious changes. We now got a first-person narration, making us feel more complicit with the protagonist’s moral dilemmas. Plus, instead of keeping his facial features suggestively mysterious through shadows and mise-en-scène, the comic now regularly rubbed our eyes on his zombie-like visage – in fact, it was plastered all over the covers:

You’d think such a decision would reflect a shift in genre – after all, the visual of a grotesque man wrapped in bandages who can assume other people’s faces seems tailor-made for horror (it’s actually the premise of Sam Raimi’s Darkman). However, I’d argue the choice had more to do with politics than genre: by having this Red Skull-looking special agent fighting on the side of the United States of America, the new creative team seemed to be implying that the Unknown Soldier’s disfigurement didn’t just make him a symbol of the generic, anonymous fighter – it made him a walking metaphor for the fact that even the Allies could be unmasked as secretly ugly. His own internal narration suggested as much, telling us that ‘a special training program had wiped away my identity, channeled my bitterness into deadly strength, honed me into a soulless war machine.’

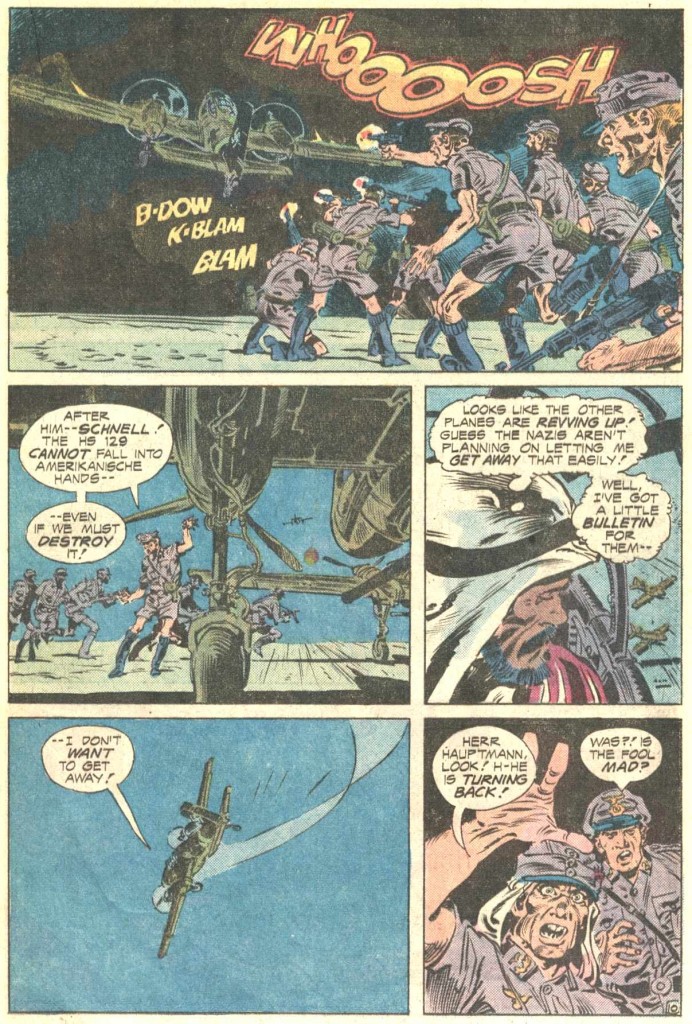

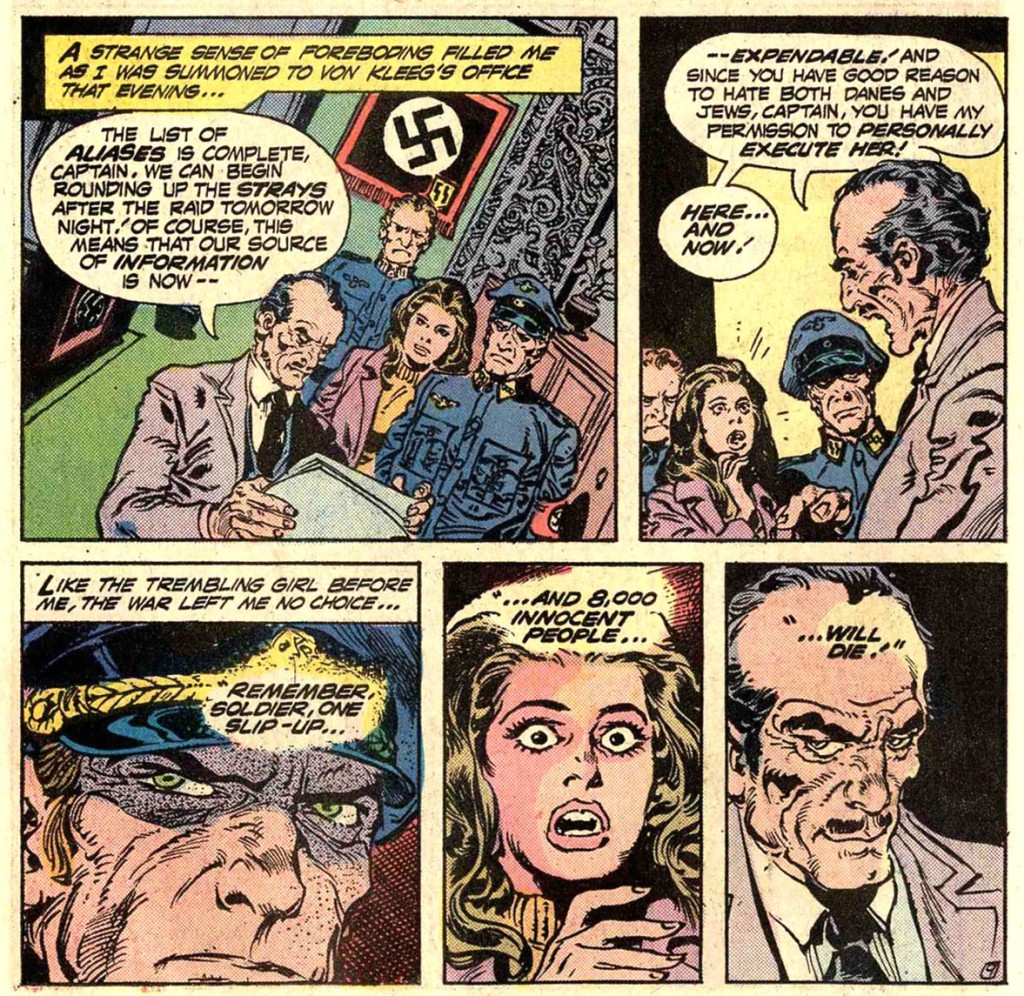

The point was that even a supposedly ‘just war’ like WWII was ultimately a horrible hell where everybody looked bad, to some degree. The notion that warfare left nobody untainted was driven home in their very first story, ‘8,000 to One,’ where the Unknown Soldier – while passing off as an SS Kommando officer in order to secure the escape of eight thousand Jews to safety – was asked to prove his loyalty by shooting a Jewish woman in cold blood:

Star Spangled War Stories #183

Star Spangled War Stories #183

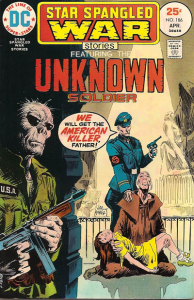

The next story was just as brutal: in ‘A Sense of Obligation,’ the Unknown Soldier is forced to shoot a man who has just saved his life, with both of them tragically aware that each is enacting a similar kind of patriotic duty. In fact, practically every story in this run involves characters having to make the difficult choice of killing someone they don’t want to kill (this includes a vicious fill-in written by Gerry Conway, titled ‘Save the Children!’).

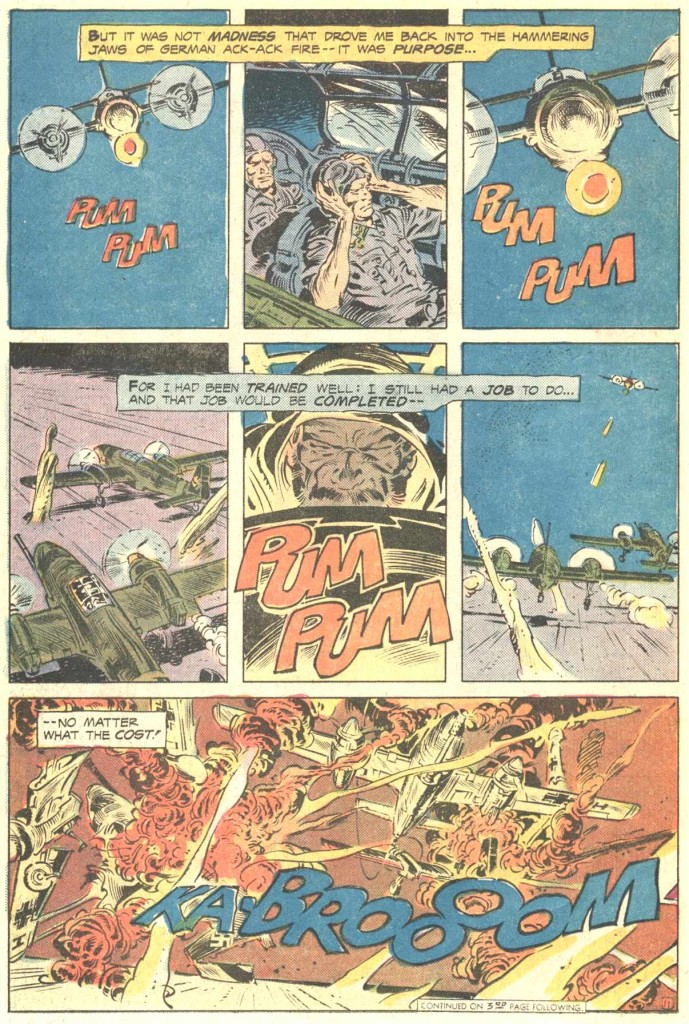

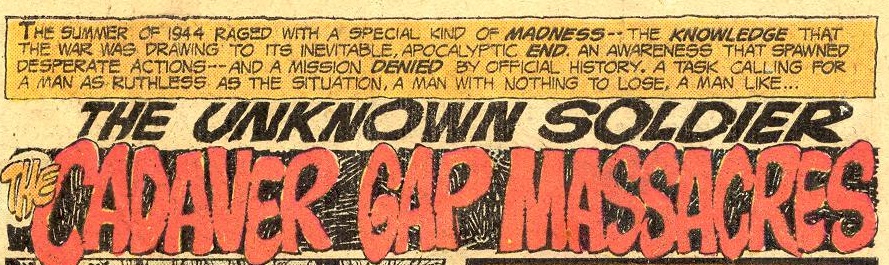

It’s not too much of a stretch to assume the creators were trying to say something about the inherently perverse nature of war. Hell, as if the book’s name wasn’t explicit enough, most tales opened with a tagline describing what was to come as ‘a story of war,’ usually together with a portentous narration and an impressively designed title…

Star Spangled War Stories #185

Star Spangled War Stories #185

As you can see, the comic was more passionate than subtle. In ‘Project: Omega’ (which possibly inspired last year’s Overlord), a German scientist creates an army of animalistic beasts. He explains that ‘I only wanted to save lives, not turn men into mindless zombies!’ – and a Nazi officer replies: ‘But, my dear doctor – what do you think good soldiers are?’ (Later in that story, you can bet there is a close-up of the doctor as he regrets ‘putting one’s patriotism… above his humanity…’)

In a way, the series became a succession of morbid morality plays…

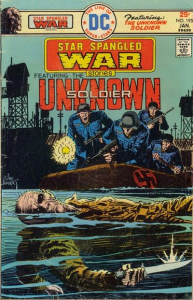

Star Spangled War Stories #202

Star Spangled War Stories #202

Since war itself (and not just the enemy) was cast as such a malignant force, the series’ hero became more of an anti-hero, as he embodied armed conflict at its most impersonal, sacrificing whomever got in the way of his missions. In this regard, the series’ tone grew closer to films like Phil Karlson’s Hornets’ Nest, which conveyed a much nastier vision of the Allies’ role in WWII.

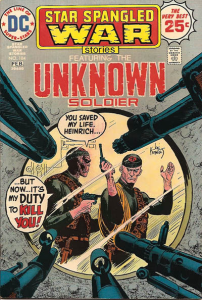

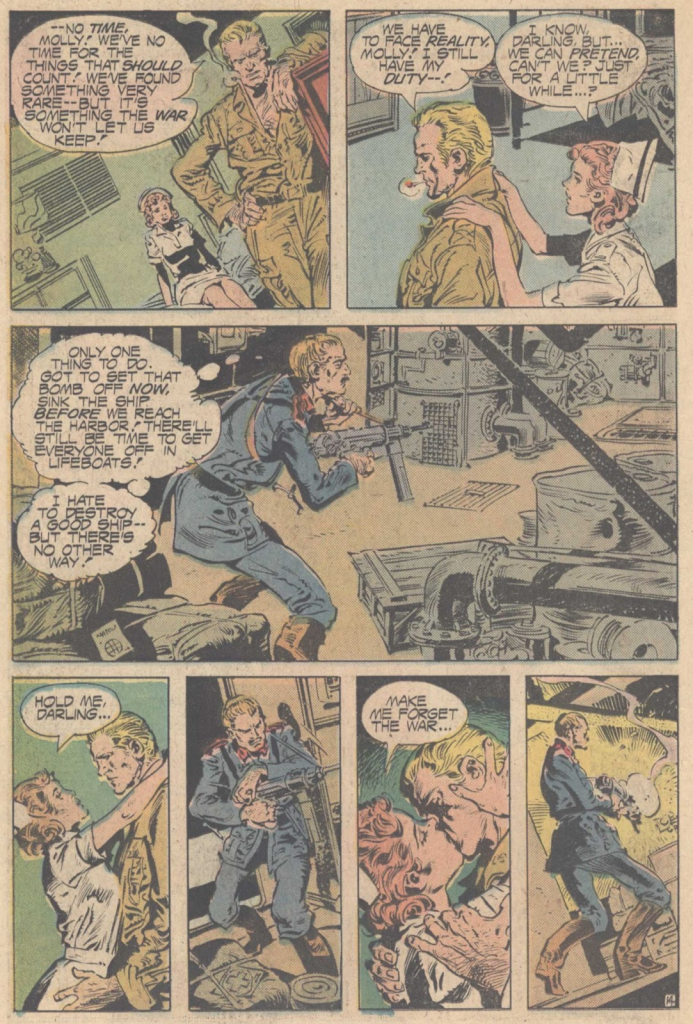

For instance, ‘Encounter’ clearly frames the Unknown Soldier as an abominable force of destruction by intercutting his actions (sabotaging a ship) with a couple of lovers (from different sides of the conflict) trying to see beyond the reality of war:

Star Spangled War Stories #184

Star Spangled War Stories #184

The amazing thing about this shift his how coherent it was with what had come before. The Unknown Soldier had always been presented as an obedient combatant and an expert in espionage – David Michelinie’s scripts didn’t contradict that, they merely reframed these elements in a dirtier light. After all, it’s not just that the Unknown Soldier represented war at a time when Vietnam had demystified the concept; he also represented covert operations, a practice that had become increasingly disreputable the more people found out about the CIA’s history of staged coups and other foreign interventions.

Thus, somehow, this WWII series became eerily timely. The 1944/1945 stories seemed to draw on the spirit of 1974/1975, with a boom of rampant, desperate ruthlessness as each war reached a climax. The text itself hinted at this parallel:

Star Spangled War Stories #189

Star Spangled War Stories #189

All this may make The Unknown Soldier sound preachy and downbeat but, like I said, the new team never fully departed from the series’ origins as a showcase for hell-for-leather adventure (it’s a classic case of having your cake and eating it too). I guess you can argue they merely rearranged the emphasis: instead of being a thrilling entertainment that occasionally acknowledged the most unappealing elements of war, the comic became an indictment of war that couldn’t help but depict it in a thrilling way (if nothing else because Gerry Talaoc’s art was so damn lively):