The conversation in the comments section of The Tempest’s post back in January got me thinking about how much of Alan Moore’s career was spent playing with other creators’ toys, providing some of the greatest gun-for-hire work in the medium… This involved relatively lengthy runs that comprehensively expanded a pre-existing mythos (Captain Britain, Marvelman, Swamp Thing, Supreme, WildC.A.T.S.), but he also wrote several hit-and-run shorts that succinctly developed small corners of large universes or even lastingly retconned bits of a series’ continuity. These are often neat comics, working as punchy short stories (Moore is a master of the format) while also drawing on our knowledge of the wider narratives in which they fit.

A few years ago, I praised Moore’s story ‘Last Night I Dreamed of Dr. Cobra,’ which brilliantly imagined a future for Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Here are another ten gems:

‘Rust Never Sleeps’ (originally published in The Empire Strikes Back Monthly #156, cover-dated May 1982), with Alan Davis (art) and Jenny O’Connor (letters)

One of Alan Moore’s earliest gigs involved writing shorts for Marvel UK’s Star Wars comics, of all places. While they’re generally readable-yet-forgettable, what makes these comics interesting is that they explore a side of the franchise that is not the one George Lucas (and his successors) ended up developing. Instead of dynastic soap opera and galactic politics, most stories revolve around different forms of fantasy beyond the Jedi mythology, positing a universe with a wider array of godlike entities and physics-defying phenomena than what we’ve seen in the Skywalker saga, which makes them pretty off-kilter from today’s vantage point. I have a fondness for ‘Rust Never Sleeps,’ in which C-3P0 and R2-D2 come across a kind of droid religion at a planet-sized junkyard. It’s an amusing tale that not only fleshes out Star Wars’ world a bit more, but which works precisely because we know about the larger conflict out there, so we realize what’s at stake better than some of the characters involved.

(The notion of exploring the outer corners of this galaxy far, far away appeals much more to me than endless retreads of world-shattering confrontations between chosen Jedis and Sith emperors, which is why I found greater satisfaction in Jon Favreau’s scaled-backed space western The Mandalorian than in the bloated, unimaginative Rise of Skywalker.)

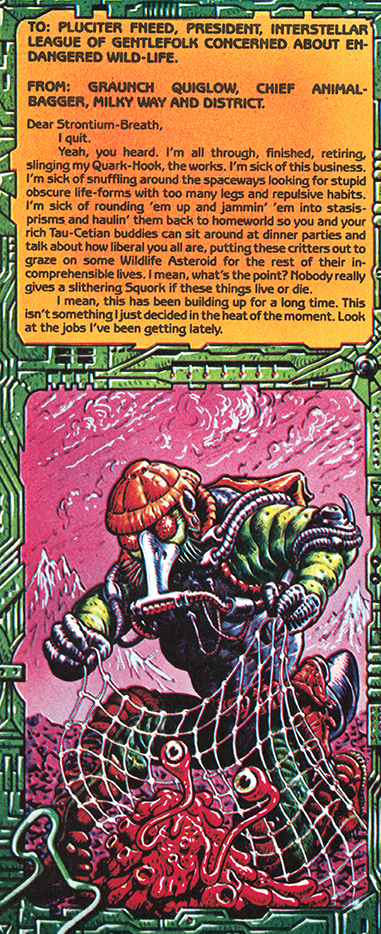

‘Protected Species’ (originally published in The Super Heroes Annual 1984, cover-dated 1984), with Bryan Talbot (art)

Besides Marvel UK, Alan Moore also did some early work for DC UK, a British publisher that mostly put out reprints of DC’s American material, plus the occasional original story. One of those originals was Moore’s Batman tale ‘The Gun,’ which I’ve discussed before. Another one was the illustrated text piece ‘Protected Species,’ written as a resignation letter from an alien hunter assigned with capturing one of the last Kryptonians alive.

It’s a pretty funny story and well worth tracking down, as Moore indulges in his underrated flair for whimsical comedy (coupled with a surprising amount of world-building): ‘Last season you sent me after those Lesser Iridescent Snicker-Fish that live out on the frozen Methane-Flats of Snorky’s Planet. Yeah, I know there’s only five of the things left in the whole Universe, but that’s not the point. The point is that I had to spend three weeks wading thorax-deep in frozen, stinking methane, looking for some ugly, radioactive-looking little squirm-ball that just giggled at me when I finally found it.’

Needless to say, the main joke is that, unlike the narrator, DC fans know exactly what he’s up against. It’s a simple two-page story, but the shift in perspective is enough to earn some solid chuckles.

‘Red Planet Blues’ (originally published in 2000 AD Annual 1985, cover-dated 1985), with Steve Dillon (pencils), John Higgins (inks), and Steve Potter (letters)

The British cyberpunk magazine 2000 AD made a name for itself with a distinctly grungy sci-fi/horror vibe, geared towards teenage boys through a misanthropic, working class attitude (you can see how the comic went on to inspire stuff like Attack the Block and Love, Death & Robots). Alan Moore fit right in, honing his craft by penning several short stories – mostly standalone ‘Future Shocks’ – as well as a few multi-part sagas. He also contributed with quick instalments for the strips Rogue Warrior, Ro-Busters, and The A.B.C. Warriors.

One of the latter, ‘Red Planet Blues,’ is a concise yet poignant tale about the human colonization of Mars. Neither the use of space as a parable about colonialism nor the move of gradually looking at the monsters as victims are exactly groundbreaking approaches (surely not on the pages of 2000 AD). However, the whole thing works because it’s told through Hammerstein’s supposedly dispassionate point of view, which ironically captures the very injustice he claims not to feel. It also helps that Steve Dillon draws him as one of the saddest-looking robots to ever grace a comic.

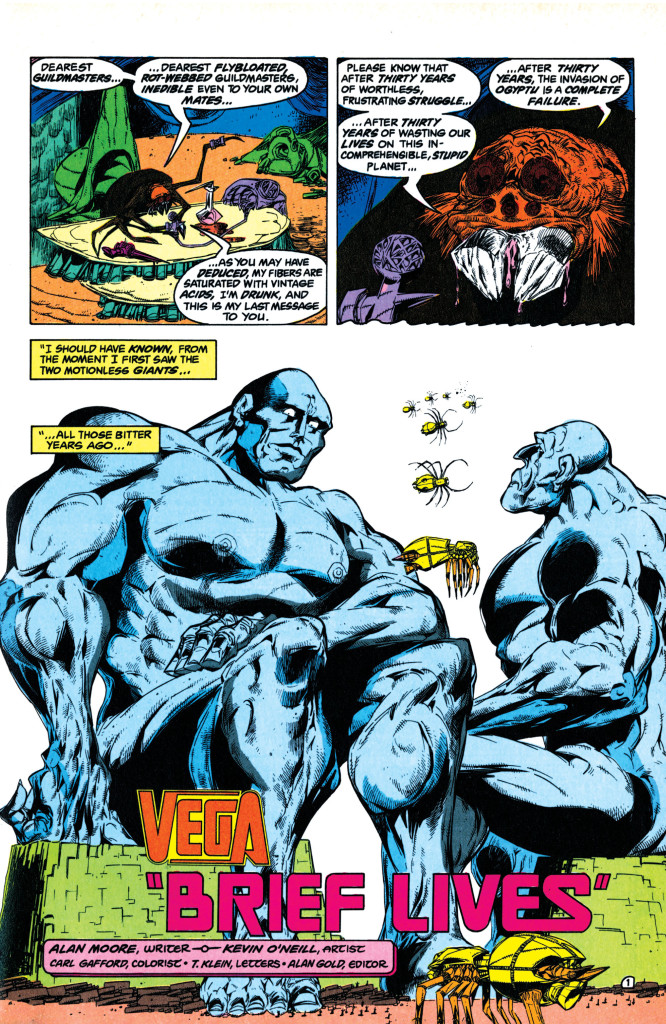

‘Brief Lives’ (originally published in The Omega Men #26, cover-dated May 1985), with Kevin O’Neill (art), Carl Gafford (colors), and Todd Klein (letters)

This one was made for DC’s The Omega Men (a series that unfortunately had no relation to the psychedelic futuristic thriller starring Charlton Heston), more specifically for the ‘Vega’ backups set around the titular planetary system. Although it features the Spider Guild (a coalition of imperialist alien arachnoids created in Green Lantern), ‘Brief Lives’ could’ve been a 2000 AD ‘Future Shock’ or ‘Time Twister’ quickie – a genuinely great one, by the way. It even includes artwork by 2000 AD alumnus Kevin O’Neill!

The premise is that this tiny spider-like species is trying to take over a planet inhabited by giants who operate in a whole different time frame, where the mere blinking of an eye lasts for ten of the invaders’ years. Their vantage point is so far apart that the Spider Guild’s challenge becomes to make the giants actually aware that they have been conquered. The result is a fun little sci-fi mind-bender that – in just four pages – amusingly tackles the relativity of time and perception (and the futility of war, from a long-term perspective). I keep waiting for people to bring it up in discussions of the Anthropocene.

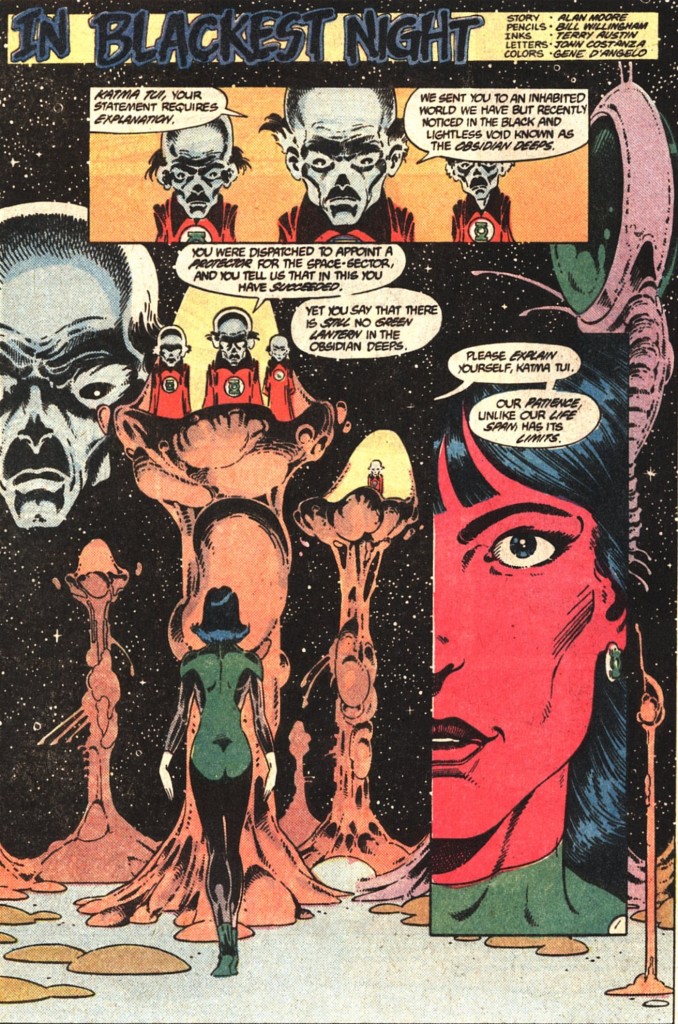

‘In Blackest Night’ (originally published in Tales of the Green Lantern Corps Annual #3, cover-dated 1987), with Bill Willingham (pencils), Terry Austin (inks), Gene D’Angelo (colors), and John Costanza (letters)

A beautiful example of Alan Moore’s knack for taking an existing concept and considering its implications in novel and clever ways. In this case, he wonders how the intergalactic space force Green Lantern Corps could possibly go about it if they wanted to recruit a member from an area of the lightless, starless cosmos, where there would be no concept of color or light – and so, by definition, where even the Green Lanterns’ name (not to mention their oath) would be untranslatable. The result is both playful (especially the final punchline) and possibly allegorical in its respectful treatment of cultural barriers.

Yes, it’s another tale about subjectivity – a recurring motif that matches Moore’s continued efforts to push readers’ perceptions (of comics, genre, and the world beyond them) in new directions.

‘Footsteps’ (originally published in Secret Origins (v2) #10, cover-dated January 1987), with Joe Orlando (art), Carl Gafford (colors), and Bob Lappan (letters)

The Phantom Stranger is one of DC’s most mysterious characters and that mystery is part of his appeal, so when editor Bob Greenberger decided to devote an issue of Secret Origins to the Phantom Stranger he wisely chose to retain some of the ambiguity by providing, not one, but four possible origin stories (by four different creative teams). Alan Moore wrote ‘Footsteps,’ which presents the Stranger – as well the demon Etrigan – as an angel caught in the War in Heaven.

There isn’t much meat on the bone, but once again it’s all in the execution. ‘Footsteps’ keeps shifting from the Phantom Stranger’s recollections of the time of Satan’s fall to a current day story about a guy torn between the NYC subway Guardian Angels and a gang of sewer survivalists. The parallels between the two tales – highlighted by Joe Orlando’s symmetrical layouts – follow the kind of symbol-laden formal exercises characteristic of Moore’s style at the time (most notably in Watchmen, The Killing Joke, and Superman’s ‘For the Man Who Has Everything’), as do the poetic narration, the tight scene transitions, and the multilayered dialogue.

(The other writers went with biblical origins as well, except for Dan Mishkin, who counterbalanced this theological slant by linking the Phantom Stranger to the Big Bang!)

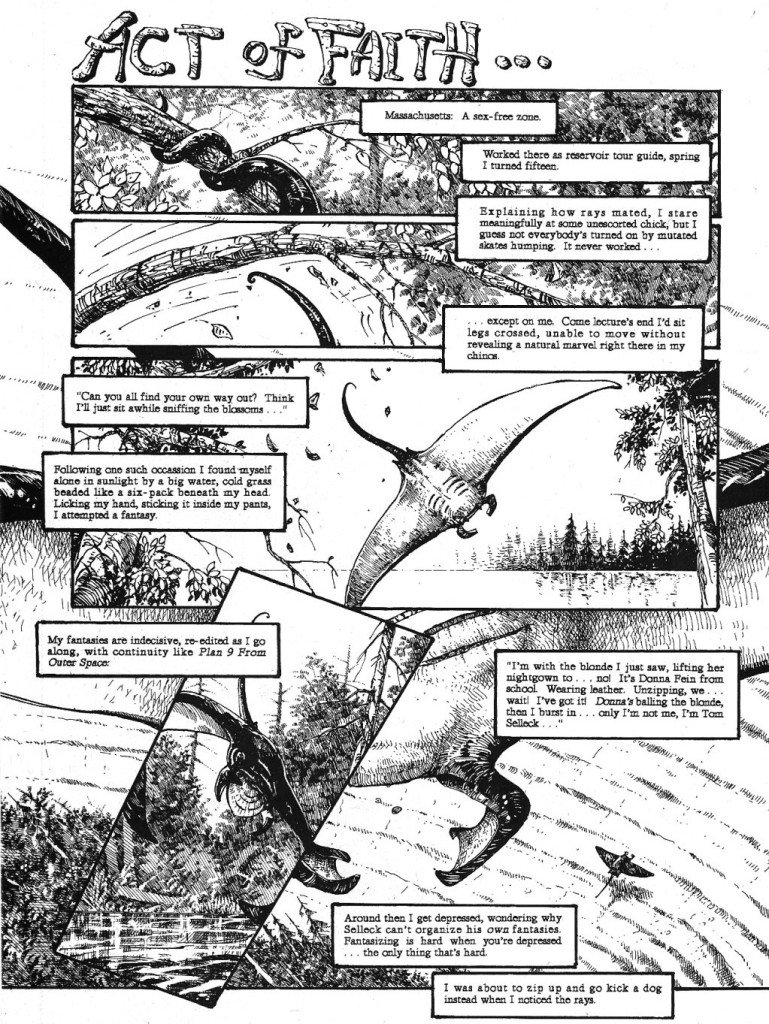

‘Act of Faith…’ (originally published in The Puma Blues #20, cover-dated 1988), with Stephen Bissette (pencils) and Michael Zulli (inks)

Given Alan Moore’s reputation, some of you may be surprised that we’ve made it so far with practically no sexual content. That’s about to change!

Through the eyes of a masturbating narrator, ‘Act of Faith…’ imagines, in rich detail, the mating habits of flying manta rays in a post-nuclear-incident year 2000. Somehow, though, this comes across as profoundly melancholic (aided by the gorgeous art!), culminating in a lovely meditation about the sense of risk and hope inherent to human reproduction at a time of deadly STDs and climate change.

I don’t know if Moore ended up writing this 4-page story because he was an avowed fan of Stephen Murphy’s and Michael Zulli’s ambitious, experimental indie comic The Puma Blues or just because he wanted to make a statement in his crusade for creators’ rights by giving the series a commercial push after Diamond Comics Distributors had refused to distribute it. In any case, the result feels deeply personal and nothing short of wonderful, creating a powerful reading experience that lines up perfectly with the humanist and environmentalist themes of this cult comic.

‘The Mirror’ (originally published in Taboo #5, cover-dated 1991), with Melinda Gebbie (art, colors) and C.D. Alexandar (letters)

Lost Girls was also a case of Alan Moore playing with other people’s toys, albeit this time around without any official authorization and not as part of anyone else’s ongoing franchise. Still, the comic does star (public domain) characters that he did not create, taken from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up. In fact, Lost Girls can even be read as a proper sequel to those works, set in their future 1914 (even if it retcons bits of their continuity). That said, while those are classics of children literature, Moore’s comic is, in turn, a very adult-oriented piece of hardcore pornography.

Lost Girls started out in the indie anthology Taboo back in the early ‘90s and, after a long hiatus, was finally completed and published as a massive graphic novel in 2006. It tells a full, cohesive story, but some of its sub-chapters are so neatly self-contained that they do work as autonomous tales as well. For instance, the very first one, the 8-page ‘The Mirror,’ can be read by itself as a bittersweet (if naughty) take on an older Alice, with an ambiguous magical twist at the end.

Moreover, unlike the rest of the book, this section is still a relatively restrained slice of erotica rather than a full-blown display of depraved sex and filth, so it may even appeal to people who aren’t that keen on reading the rest. As you can see above, it’s all framed by Alice’s mirror (a nod to Through the Looking-Glass) and tastefully illustrated by Melinda Gebbie, who elegantly sets up the comic’s precise mise en scène and fauvist tones.

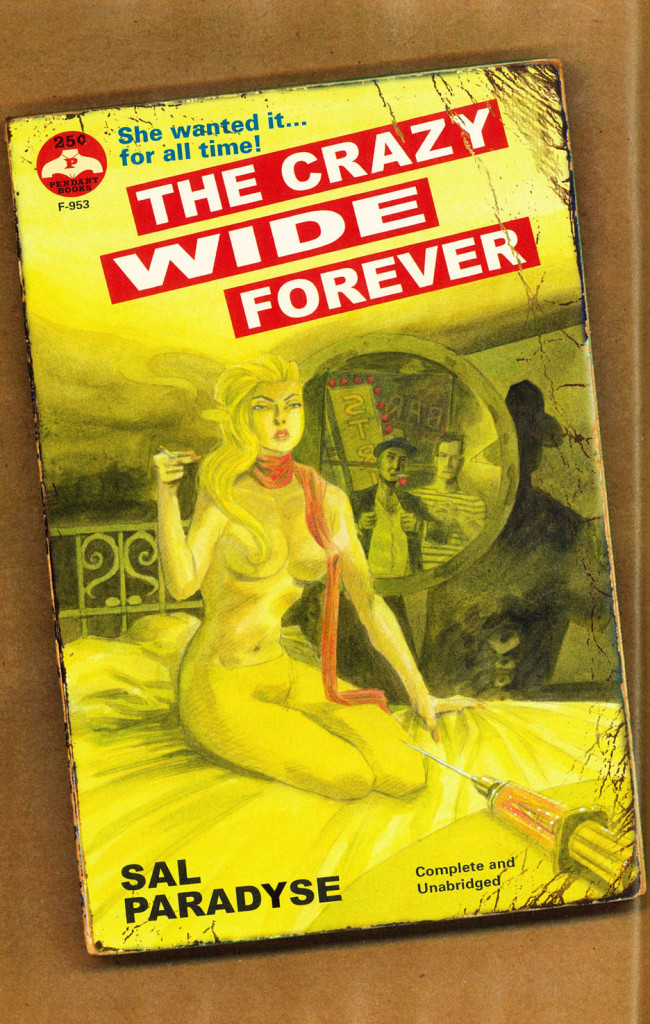

‘The Crazy Wide Forever’ (originally published in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier, cover-dated 2008), with Kevin O’Neill (art), Ben Dimagmaliw (colors), and Todd Klein (letters)

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen took the idea behind Lost Girls all the way by stealing hundreds of characters from all sorts of creators and building on their established history, making it the ultimate example of Moore playing in other people’s sandboxes (or, if you prefer, ransacking those sandboxes and then bringing other people’s toys into his own sandbox). Notably, he didn’t just use pre-existing concepts and characters, but also mimicked formal styles, especially in Black Dossier, which was essentially a loosely connected anthology of pastiches merging different intellectual properties. This included an excerpt of ‘The Crazy Wide Forever,’ a book-within-a-book written by Sal Paradyse (Jack Kerouac’s fictional stand-in from On the Road) in a beatnik style reminiscent of Kerouac’s and William S. Burroughs’ prose (Burroughs, in particular, being a major influence on Moore).

This 5-page short story (plus the mock cover you see above, by Moore’s regular partner in crime, Kevin O’Neill) is kind of an epilogue to LOEG’s first volume, in which Professor Moriarty tried to blow up Fu Manchu, but was prevented by Dracula’s Mina Murray and King Solomon’s Mines’ Allan Quatermain. In ‘The Crazy Wide Forever,’ the titular lead of Kerouac’s Doctor Sax (here called Dr. Sachs), who turns out to be Fu Manchu’s grandson, goes after Moriarty and ends up almost unleashing H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu.

If you think this already sounds delirious, wait until you get a load of Moore’s version of beatnik spontaneous prose: ‘…Dr. Sachs flaps back above the chimney stacks and sacks the railroad tracks what run like suicide into the weeds he feeds on needs an greeds bleeds into telegraph transmissions scrambles messages to random voodoo poetry he is the scrawled phone number what makes lovers fight and I will tell you this of infamy he is Mahatma in the Mission district’s tinders he makes winos dream that there’s no cigarette alight between their fingers uz they slobber down to sleep…’

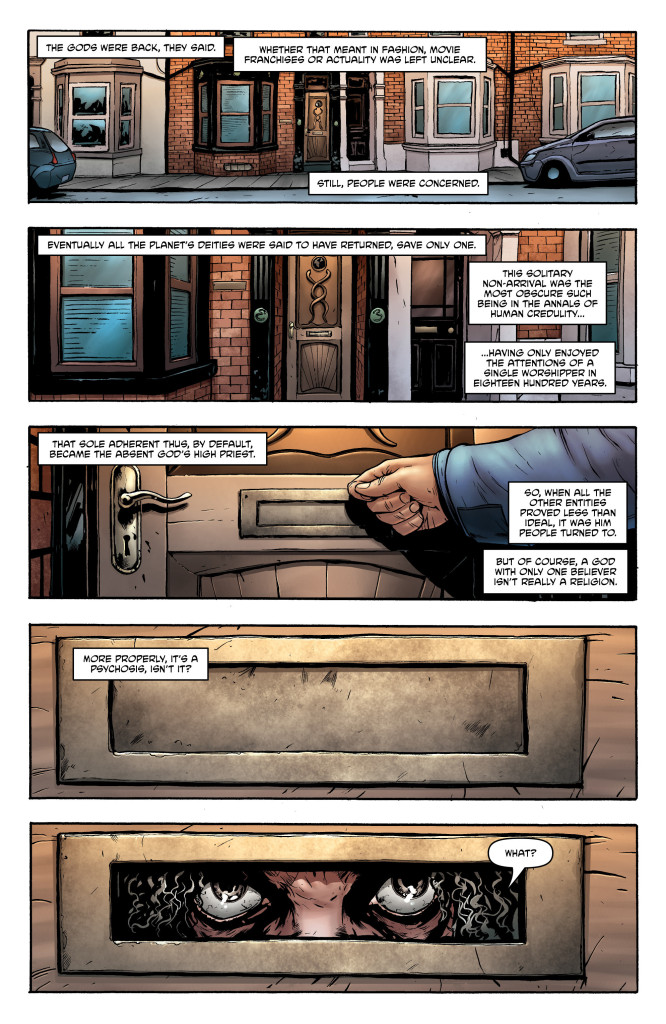

‘Grandeur and Monstrosity’ (originally published in God Is Dead: The Book of Acts #Alpha, cover-dated July 2014), with Facundo Percio (art), Hernan Cabrera (colors), and Kurt Hathaway (letters)

One of Moore’s last safe havens of indie publishing was Avatar Press, which specializes in a particularly extreme brand of taboo-breaking horror, packed with no-holds-barred nudity, swearing, graphic violence, and gleeful blasphemy (notably, the publisher’s catalogue includes Über, Crossed, Strange Kiss, and Chronicles of Wormwood). A few years ago, one of my guilty pleasures from Avatar was God Is Dead, in which all sorts of gods came to life. Created by Jonathan Hickman and Mike Costa, the series was basically a religious crossover pitting the pantheons of various mythologies against each other… Like in your average large-scale multi-company event, most characters weren’t particularly well-developed, so your enjoyment relied on the geeky pleasure of recognition and the shock value of seeing familiar figures mercilessly slaughter each other (look, the Valkyries are slaying Atlas!). I appreciated God Is Dead’s iconoclastic exuberance for a while, but eventually dropped out because it amounted to so very little more than the occasional puerile thrill.

Along with the regular series, though, Avatar published a couple of specials in which guest creators contributed with side stories. Alan Moore, who has famously proclaimed himself the High Priest of a one-person cult to the Roman snake god Glycon, went with a surprisingly personal, metafictional approach: in the story, Moore’s fans, still confused about how literally to take his odd religion, ask him whether his god, too, has come to life. In response, Moore gives a performance at the O2 Arena which consists of him holding a puppet of Glycon that lectures the crowd about Neo-Platonism (which saw gods as conceptual essences without material form). The whole thing is crammed with inside jokes and absurdist wit, like when the narration tells us that ‘the show started slightly later than advertised. Long enough, in fact, for some audience members to write lengthy dissertations on the empty stage as a conceptual art statement.’

Of course, if gods are ultimately ideas expressed through representation, then the fact that Glycon is admittedly a puppet doesn’t make it less of a god (only a more honest, revealing one). Yet that also means that the notion of gods coming to life in the flesh makes little sense, since, according to this interpretation, their godliness is defined precisely by the fact that they can only manifest themselves through the works they inspire. In other words, ‘Grandeur and Monstrosity’ both mocks God Is Dead and nicely delves into the series’ themes. Thus, in a pleasing balancing act, Moore manages to do a humorous short story set (and published) in the periphery of a trashy comic that also cogently conveys one of his oeuvre’s major running philosophical motifs: ‘Are gods unreal, then? Not at all. As ideas, we have changed your world beyond all recognition. We have brought enlightenment and slaughter. Do not doubt our power. Just try not to be so literal.’

I’ll also always have a soft spot for the little meta story ‘In Pictopia’ from Anything Goes, and for that kooky Kool-Aid Man short gag story Moore did with Peter Bagge.