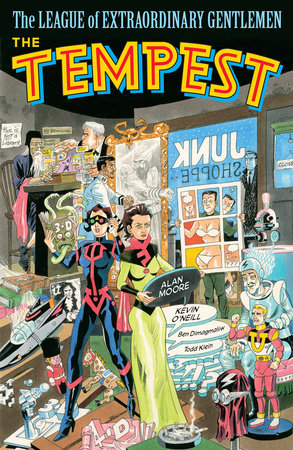

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, Gotham Calling’s 2019 book of the year is The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Tempest. There were other strong contenders, most notably the first volume of Chris Ware’s Rusty Brown, with its geometric meta-narratives that continuously rework the medium’s grammar, borrowing techniques from infographics, reductive art, and modernist literature in the service of devastating tales about ageing, alienation, and skeevy voyeurism. Yet I ended up going with this collection of the mini-series (plus a droll 4-page epilogue) that served as the apocalyptic culmination of Alan Moore’s and Kevin O’Neill’s esoteric tour-de-force linking all sorts of stories and characters from various media and genres across the ages. In part, I did it because Moore has announced his retirement from the medium he has so profoundly changed, so the book feels like a final conflicted love/hate letter to his origins.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is not an easy series to plough through, so those who’ve made it this far probably know what they’re getting into. Whatever you love or hate about LOEG’s previous volumes, you’re likely to find it in The Tempest, only even more so. Picking up where Century: 2009 left off, this final volume kicks off with the series’ peculiar versions of Dracula’s Wilhelmina Murray, the protagonist of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and Emma Peel from The Avengers (the 1960s’ spy show, not Marvel’s super-team) being hunted by a rebooted James Bond, which eventually leads to an all-out war between fantasy and humanity (which may or may not be a metaphor for the ‘fake news’ era). As usual, there is plenty of mean comedy and such an omnivorous, insurmountable barrage of references that the best format for The Tempest would ideally be a web comic with hyperlinks to Jesse Nevins’ annotations.

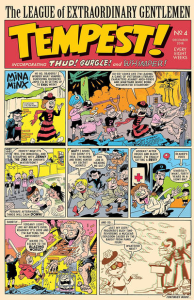

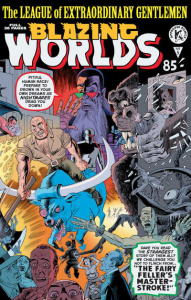

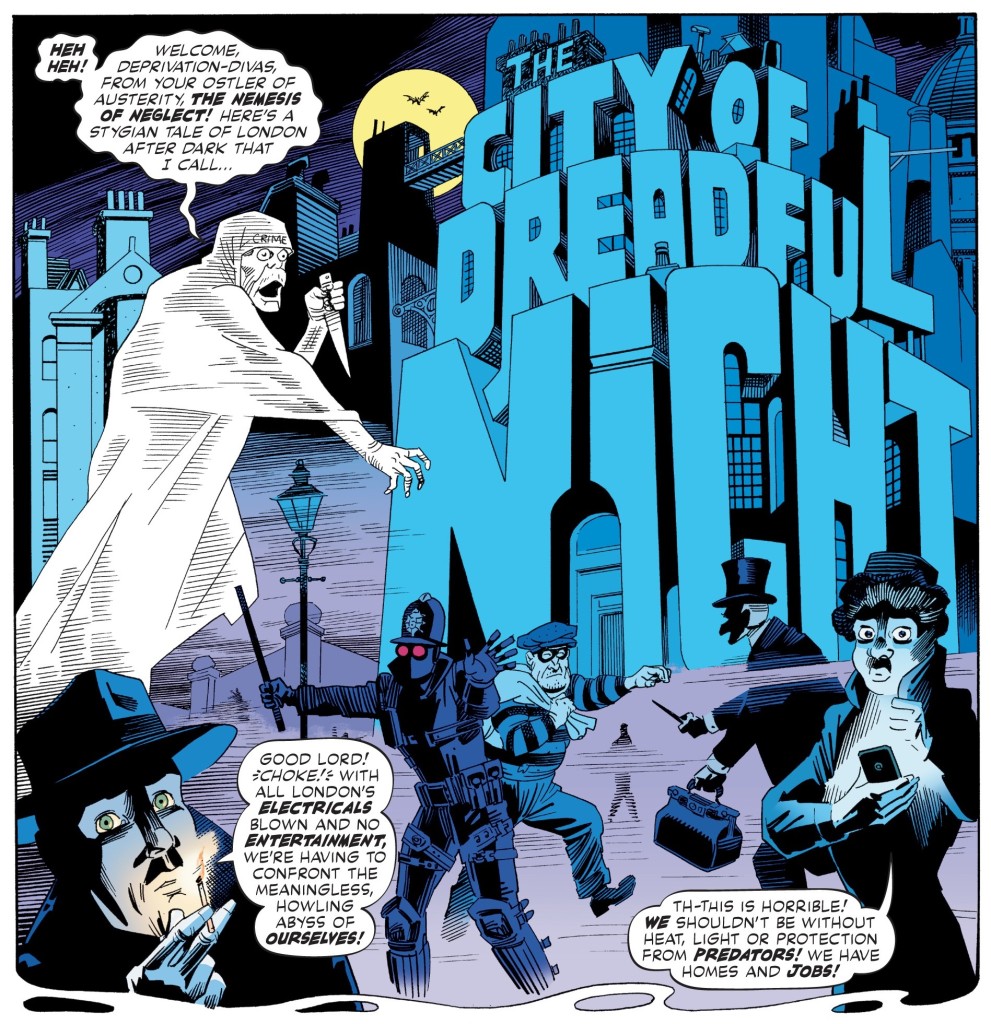

Even the covers are chockful of in-jokes and allusions:

I actually agree with some of the criticism that has been levelled at the series (like how LOEG mocks patriarchal Western imperialism while indulging in many of the attitudes and stereotypes that inform this ideology), which doesn’t mean I don’t get a kick out of it. I especially love the very eccentricity of the whole thing: LOEG is a messy postmodern satirical alternate history / mega-crossover comic book series aimed at extremely well-read adults that, like Alan Moore, share a passion for – and an encyclopedic knowledge of – both high culture and bawdy pulp fiction. You can add to this Kevin O’Neill’s and Ben Dimagmaliw’s lavish, unnaturalistic artwork and colors. And the fact that the series contains so much graphic and explicit sex – and not just for the standards of a comic initially distributed by a major mainstream publisher – that some of its entries (Black Dossier and Century, in particular) are essentially literate sex comics.

The result is a dense text, piling layers upon layers of fiction while telling a massively sprawling saga (in cast, geography, and chronology) through multiple formats: not just your average comic book storytelling, but also intricate prose (including the largely descriptive ‘New Traveller’s Almanac’ in volume II), 3-D sequences, poetry, cartoons, games, and advertisements. It’s also packed with surreal humor, like The Tempest’s hilarious flashback sequence in which Captain Universe fights an incarnation of the abstract concept of infinity (‘Merely to contemplate me has driven men mad!’).

The agenda of blurring the lines between high, middle, and lowbrow is close to my heart (as you can probably tell by some of the posts in this blog). Besides, at its best, all this takes the form of a fun and thrilling affair. And while some may complain that the fun and thrills rely on extensive previous knowledge, that’s missing the point: by this stage, LOEG has long left any pretentions it might have had (and which it probably never did have) of working as a more-or-less standalone adventure saga. Rather, it’s a comic *precisely* about the fun and thrills of intertextuality!

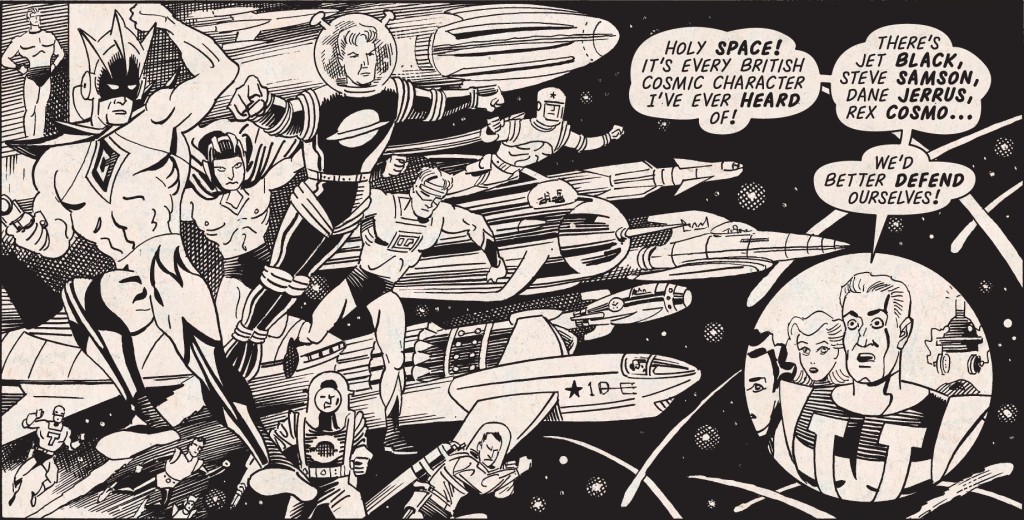

Although I didn’t know many of the secondary characters, I had a blast finding out more about them online and tracking down some of their original appearances (for all its backwards-looking attitude, LOEG is quite a twenty-first century reading experience, taking full advantage of the modern information age). It also made it even more gratifying every time the book did engage with works I was familiar with (ah, so that’s how Yevgwny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We fits into this world… and even though they can’t say his actual name for copyright reasons, that’s definitely an older Brain Boy working with Captain Universe!).

It’s not just that the cast and concepts are borrowed from other works. Like they did in Black Dossier, Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill fill The Tempest with formal pastiches. Once again, while ultra-versatile letterer Todd Klein perfectly mimics the fonts from different periods, O’Neill isn’t as chameleonic – his talent consists of evoking the various publishing traditions while fusing them with LOEG’s own distinctive style. The twist is that in The Tempest the primary dialogue is no longer just with literature and audiovisual fiction, but specifically with British comic books. Some of the subplots are told in the format of daily newspaper serials, literary adaptations from Classics Illustrated, photonovels, soccer comics, and 2000 AD strips, among many other riffs. There is even a tribute to reprints of Will Eisner’s The Spirit and EC Comics’ horror short stories:

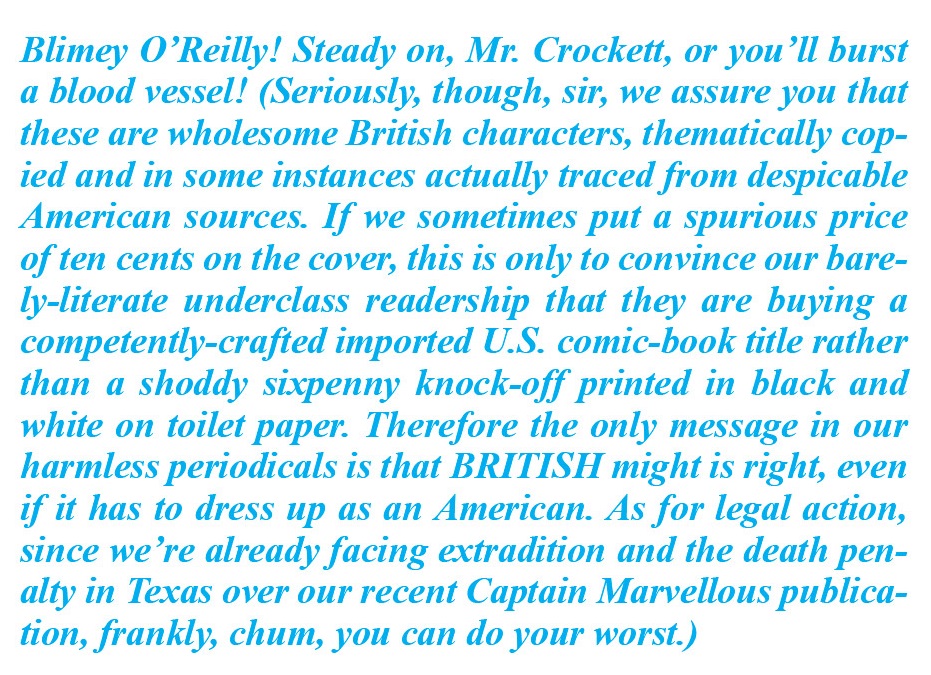

Moreover, each issue is framed like one those 1960s’ magazines ripping off US superhero comics in black and white – or, as the fake letter column aptly puts it:

Besides being a pretext for Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill to spoof the kind of material they read as kids (and which directly led to Moore’s first masterpiece, Marvelman), this framing device ties in neatly with The Tempest’s themes, both because some of the action involves a British group that’s a thinly-veiled knock-off of American super-teams and because the whole book’s leitmotif is a comment on the comic industry’s long history of exploitation and appropriation. From the onset, much of LOEG has been about exposing what classic fictional characters represented (colonialist ideals, repressed sexuality, etc), just like in Moore’s other intertextual opuses: the proudly pornographic Lost Girls and the Lovecraftian horror saga Providence. Here, though, his main target appears to be the very industry – its practices and underlying philosophy – behind the production of the original works. There is even a recurring opening feature called ‘Cheated Champions of Your Childhood’ denouncing the treatment of different creators in a parodic-yet-heartfelt tone.

As a result, we get not only a fitting end to the series, but a fitting end to the comic-writing journey of the mad genius from Northampton. Like Shakeaspere, Alan Moore closes his career with The Tempest (that play’s association with finality was also tapped by Neil Gaiman, who visited it in the final issue of his own metafictional fantasy epic The Sandman). Moore goes out trashing the archetypes that dominated twentieth-century comics (and today’s screens), cheekily responding to some of the criticism of his later work (especially in the final letter column), and settling countless old scores, like Marvelman’s forced change to Miraclemen (alluded to in the column above), DC’s refusal to include a recording of ‘Immortal Love‘ in Black Dossier, or his longstanding accusation that he was cheated out of the rights to Watchmen.

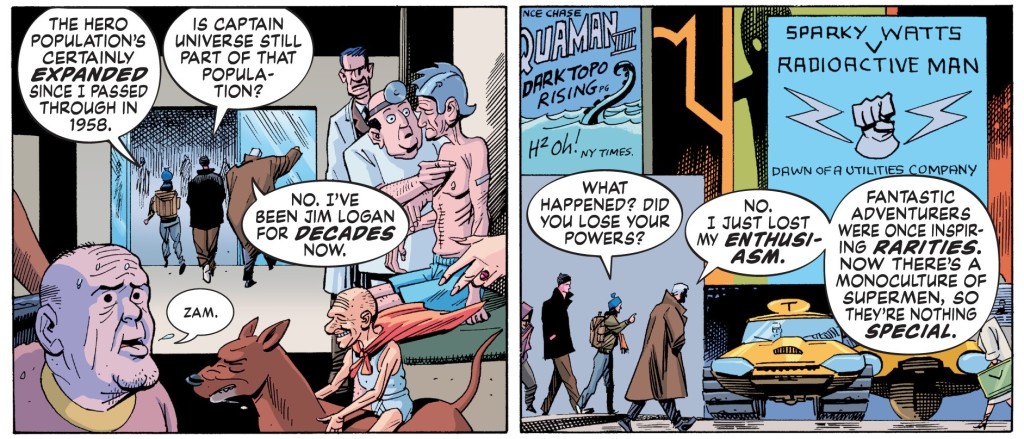

In a not-exactly-subtle jab at the biggest publishers in the field, he even presents us with a superhero retirement home full of moribund old characters/intellectual properties:

Now, for the elephant in the room: some people see a contradiction in the fact that Moore has been so outspoken against what others have done with his creations while gleefully pillaging other creators’ babies in LOEG and treating them quite disrespectfully himself. I don’t think it’s quite comparable, though… From what I’ve seen online – which is not much, admittedly – his rants have more to do with the lack of imagination of writers who seem stuck on his old stories and the misinterpretation of his comics’ politico-literary agendas by movies like From Hell and V for Vendetta. There is a case to be made that a writer engaging with other people’s books in thoughtful and original ways isn’t the same as having a mega-corporation take rights away from creators and subsequently exploit their initial work through ill-conceived products that thrive on brand recognition.

From a consumer perspective, my main issue has always been that an abundance of uninspired ancillary products tends to taint the source material – both in my mind (all the extra baggage undermines the original’s purity in my memory) and in my favorite hobby, which is to recommend books to other people (even when having seen a lame adaptation doesn’t put people off from checking the original, knowing the story certainly lessens the impact of the subsequent reading experience). Sure, some texts are more sacred than others. I feel more protective of the perfectly self-contained Watchmen – with its stark authorial vision – than of serials that have been around in multiple interpretations since decades before I was born and whose original iteration isn’t all that brilliant (for all their klutzy charm, the most appealing thing about many early Superman comics is their function as urtext for later tales). The thing with Watchmen is that so much of what makes that book so special has to do with its formal experimentation, its radical departure from what came before, and its sophisticated political subtext, so attempts to mimic it without a comparable scope of ambition, innovation, or depth seem particularly pointless.

(Having finally caved in and watched Damon Lindelof’s bizarre Watchmen sequel TV show, though, I will give it kudos for at least taking the material in a truly unexpected direction, most notably with the focus on race and the Moore-ish twist on Hooded Justice. I liked some of the world-building around Redford’s liberal utopia, incorporating tensions rather than going for a simplistic anti-PC caricature (a la Black Science #41). The meta-parodies of Zack Snyder and Chris Nolan were not only cute, but pertinent – after all, if you’re reimagining audiovisual superheroes today, you have to engage with the genre’s evolution. That said, the abundant callbacks to the comic became more distracting than rewarding – and the safe, righteous ending was especially disappointing when compared to the original’s morally discomforting fantastic-solution-to-realistic-problem payoff.)

The truth is that Alan Moore has always been a master of revisionism, having kicked off his career with mind-blowing retcons of existing properties like Captain Britain, Marvelman, and Swamp Thing. Yet his revisions always added more than they took away: they expanded the characters’ potential and explored the underlying existentialist issues at their core, telling stories that felt poignant and fresh. LOEG has somehow taken this even further, retconning much of the pop culture canon in one glorious sweeping motion.

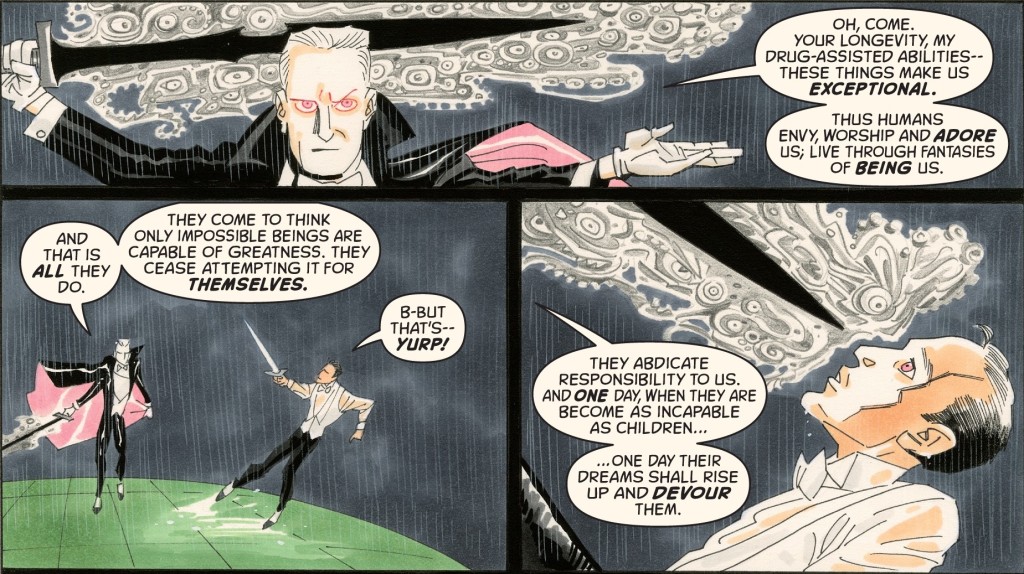

That said, The Tempest is unabashedly shaped by disenchantment. When a character explains that she came from the future, another one amusingly retorts: ‘There’s a future, other than just rebooting the 20th century forever? Wonders will never cease.’ Later on, you get statements like the one in the panels above (drawn in a style reminiscent of Eagle magazine), seemingly indicting Moore’s own fans, which reverses the spirit of Prospero’s closing monologue in Black Dossier – and, indeed, rather than a utopic celebration of fiction’s benign, aspirational role, Prospero’s Blazing World now comes across as utterly disturbing and threatening.

If Watchmen darkened superheroes by imbuing them with gritty, pretentious realism and if the America’s Best Comics line (where LOEG first got started) was at the forefront of a movement towards bringing lighthearted wonder back to comics, Alan Moore now seems to have come full circle, with a vociferous repudiation of escapist fantasy. It’s a curious balancing act, however, since The Tempest is built around winks to the inner circle, wallowing in nerdy arcana, playing with specific references (instead of generic tropes) and rewarding those who recognize most cameos (like in the splash with all the werewolves of London), implicitly challenging readers to look up other books.

This is what makes it such a fascinating object. Its bile is not the elitist contempt from smug outsiders, but the self-critical reappraisal of someone who has lived in this place (and, in fact, helped build large chunks of it) for decades and is trying to get everything out of his system before moving on. It brings to mind a passage from Jerusalem‘s chapter about Dave Daniels:

“At age thirteen, David’s idea of heaven was somewhere that comics were acclaimed and readily available, perhaps with dozens of big budget movies featuring his favourite obscure costumed characters. Now that he’s in his fifties and his paradise is all around him he finds it depressing. Concepts and ideas meant for the children of some forty years ago: is that the best that the twenty-first century has got to offer? When all this extraordinary stuff is happening everywhere, are Stan Lee’s post-war fantasies of white neurotic middle-class American empowerment really the most adequate response?”

The Tempest’s final issue drives the point home. A retired Sherlock Holmes posits his own criticism of the individualistic heroic ideal. When Captain Nemo’s great-grandson blows up his science-pirate island, he muses: ‘Put to the torch the soaring kingdom of my childhood, with all its marvels.’ Underneath all the gorgeous mayhem and gags, we are left with a provocative and very personal farewell by one of the greatest figures in the history of comics…

In the end it all just feels like a weary protestation from a burnt man left cynical on everything, and in turn that makes this reader, at least, just as weary and cynical of Moore himself.

Let’s face it, pretty much everything noteworthy the man has ever done (out of the rare exception to the rule like Big Numbers or A Small Killing) is a pastiche or parody of someone else’s ideas, even without going on the work he did on actual corporate intellectual properties (Batman, Superman, Star Wars, Spawn, Captain Britain).

1963, Miracleman, that Kool-Aid Man comic, his Pictopia story, Tom Strong, Lost Girls, Neonomicon, Supreme, Cinema Purgatorio, America’s Best Comics, Promethea, the Boejjfries Saga (which owes a fair lot to the Addams Family), the League itself. It’s all ruminating and developing or chewing on ideas others had, so when Moore in turn accuses others of lack of originality or just recycling stuff he feels hypocritical, hollow. He should look into a mirror, or perhaps he’s already had, and that’s why he retired from comics. He knows she can’t actually come with all new all original ideas while telling others they should, so he flees the field before we can see the Emperor has been naked the whole time.

The man’s always been talented. But for all the vision he’s had, it’s also often conveniently centered wherever it suits his argument. And ultimately, his bitterness and disenchantment at the content of the medium itself is mostly born from how the showrunners treated him, rather than an actual desire to branch out to all new untested fields. He had plenty of time to try that. He spent most of it on the pastiches and homages mentioned above instead.

Like so many others who fancy themselves revolutionary, Moore chastises us for not having reinvented the wheel when he hasn’t done it himself either. He’s made plenty of fanciful, functional, improved wheels, to be sure. But he’s not broken the paradigms he calls inferior and outdated, he’s just played with them and called it a day. He still fell short, in a way, and perhaps it’s an impossible task for anyone.

Perhaps he did as much as a talented person conceivably could, because the old storytelling motifs will always need to be recycled as generations themselves recycle themselves and each old fashioned comic will always be new and fresh to someone still just starting them. So these stories still have their place too and shouldn’t be overlooked just because they were produced by a system run by men who burned Alan Moore over.

That, I think, is the lesson Alan Moore himself should learn. I don’t think he truly has, from the way he phrases his ideas.

I see your point, but I wouldn’t go that far. Yes, with notable exceptions (I would add From Hell and Halo Jones to Big Numbers and A Small Killing), most Moore comics take as point of departure existing characters or concepts, but his contribution tends to go way beyond mere pastiche/parody or just updating/improving the formula (i.e. 1963 is the exception, not the rule). Although there is a lot of recycling going on, there has always been more than a fair share of originality as well: even when working within a set genre or a specific property, Moore often tries to break new ground, to engage with the material in a reflexive, illuminating way, and to provide multiple thought-provoking layers of meaning (not to mention all the formal experimentation he has brought to the medium).

And he has branched out into other fields, including music, performance, and at least a couple of breathtaking novels (granted, Jerusalem also includes a few pastiches – of Beckett and Joyce – but they make for a small section of a massive book).

That said, in the little I’ve seen from Alan Moore’s online interviews he does come across as a curmudgeon disingenuously ranting against demagogical strawmen. One of the reasons I usually avoid creators’ interviews is precisely that their public personas and unfiltered ideas often annoy me, which makes it harder for me to immerse myself in their works afterwards. Regardless, Moore has blown my mind so many times before that I trust he will do so again, in whatever medium he chooses to attack next!

“One of the reasons I usually avoid creators’ interviews is precisely that their public personas and unfiltered ideas often annoy me, which makes it harder for me to immerse myself in their works afterwards.”

The Dave Sim Syndrome, I call it. Most of Cerebus was a joy to read (by Glamourpuss even Sim’s actual comics ouput is all but unreadable. Cerebus in Hell is very dumb but harmless fun though), but dear Heavens, the man’s rants and points are despicable to read through, so he’s like the most extreme example of this phenomena of sorts that I can think of.

I agree Moore can put a lot of new and fascinating, thought provoking spins on old subjects, but at the end of the day I think they’re still the old subjects with a much needed added depth rather than all together new subjects, but then again, like I said, arguably everything has been said in one way or another through human history, and this may apply to far more than comics. We may be unable to find anything but new ways to express those things.

I don’t blame Moore for not doing more than he already has, but I don’t believe he should be so dismissive of the genres that inspired him, like the superhero one, just because they are more popular than the ones he favors now and because he had awful experiences with the men handling them. In the end the superhero ideal is as good an inspiring model to help our fellow man as any other, in a way.

I’d say it’s particularly true of genre fiction, where the most appealing aspects (reworking familiar tropes, building on preexisting expectations…) can also be quite limiting. I think you can do imaginative, surprising, and relevant things within genre and use superhero comics to express new and interesting ideas, even if I share Moore’s distrust of any hegemonic form of narrative (because there can never be one type of story that captures the rich and evolving variety of human experience).