If you read last weeks’ posts, you know what’s going on. Here are four 2020 books that reminded me of why I love comics:

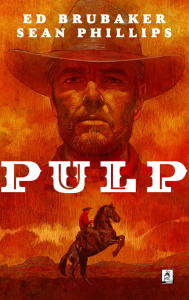

8. PULP

The creative duo of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips (known among some fans as Brubillips) have carved out a peculiar place in the field, regularly putting out critically acclaimed crime comics in the form of different projects, disconnected from larger franchises, which appeal both to nerdy aficionados and to a broader strain of readers who aren’t generally into comics at all. Their work can actually be described as having a mature, literary sensibility in the best sense of those terms: not ‘mature’ in the sense of featuring gratuitous R-rated content, but in the sense of developing a cast with realistic psychology; not ‘literary’ in the sense of sounding pompous or mannered, but in the sense of engaging with ambitious themes and emotional depth while avoiding sensationalism.

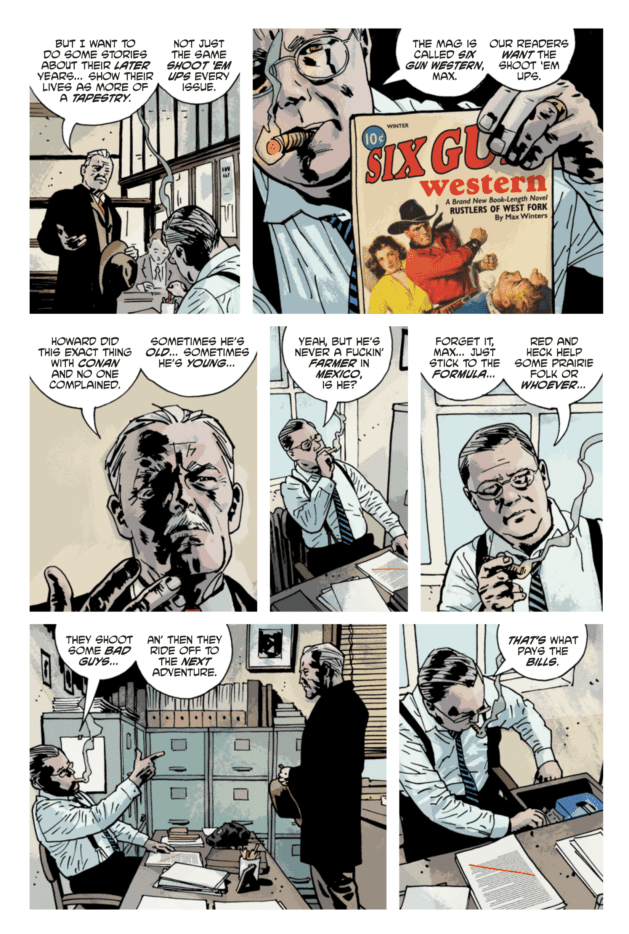

For all their ostensive realism, the focus is very often on fiction: Brubaker seems to be writing odes to – or, better yet, meditations on – the kind of noirish books and films that influenced him (and on the environment that produced those works, back in the day). His output rarely transcends those sources at their best, but it nevertheless adds up to rock-solid genre entries with compelling characterization and plotting. Phillips elevates the material: while the stories often riff on classic movies, his unfussy figure work doesn’t so much bring to mind the language of film as the aesthetics of film posters, not to mention paperback covers and the illustrations of pulp magazines. It’s the tension between that dream world and the overall grounded tone that gives these comics such a distinct personality.

Besides the latest installment of their ongoing crime saga Criminal (‘Cruel Summer’) and the first volume of their new series (Reckless), in 2020 Brubillips put out the original graphic novel Pulp, about Max Winters, an aging pulp writer of western yarns in the late 1930s whose life – past and present – turns out to be much closer to the breed of violent thrillers he typically describes in his stories. Again, there is a fascination with the history of cultural production (the scenes with Winters’ publisher are on point for the subject matter, but they also feel like Brubaker settling scores with the comic book industry) and a conscious, if subdued, remix of genre tropes: while this list’s other neo-western, Undone by Blood, was imbued with 1970s’ exploitation, Pulp taps into the subgenres of film noir, back-from-retirement-for-one-last-job heists, and vigilante justice.

The period setting allows for more than a genre exercise. The book also effectively uses this era, in which the German American Bund was advocating fascism in the US, to provide a displaced revenge fantasy against Trump supporters.

The period setting allows for more than a genre exercise. The book also effectively uses this era, in which the German American Bund was advocating fascism in the US, to provide a displaced revenge fantasy against Trump supporters.

The intertextuality and the political parallel, however, don’t get in the way of a fine read that works by itself, strong on atmosphere and with plenty of affecting passages (‘And this room is just another room where I don’t want to die.’). Pulp empathically captures the sense of weariness and malaise that comes with getting older, which gained additional resonance in a year marked by so much contempt for the lives of senior citizens… Indeed, it’s a melancholic affair, nailed by colorist Jacob Phillips’ tonal range (wintery in the present, autumnal in the past), which distinguishes the fiction-within-fiction portions through an inspired visual that comes across as a combination of watercolors and faded crayons. (Yes, Jason Wordie used a variation of this technique in the book-within-the-book portions of Undone by Blood, but the effect is even more pronounced here.)

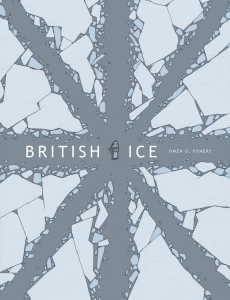

7. BRITISH ICE

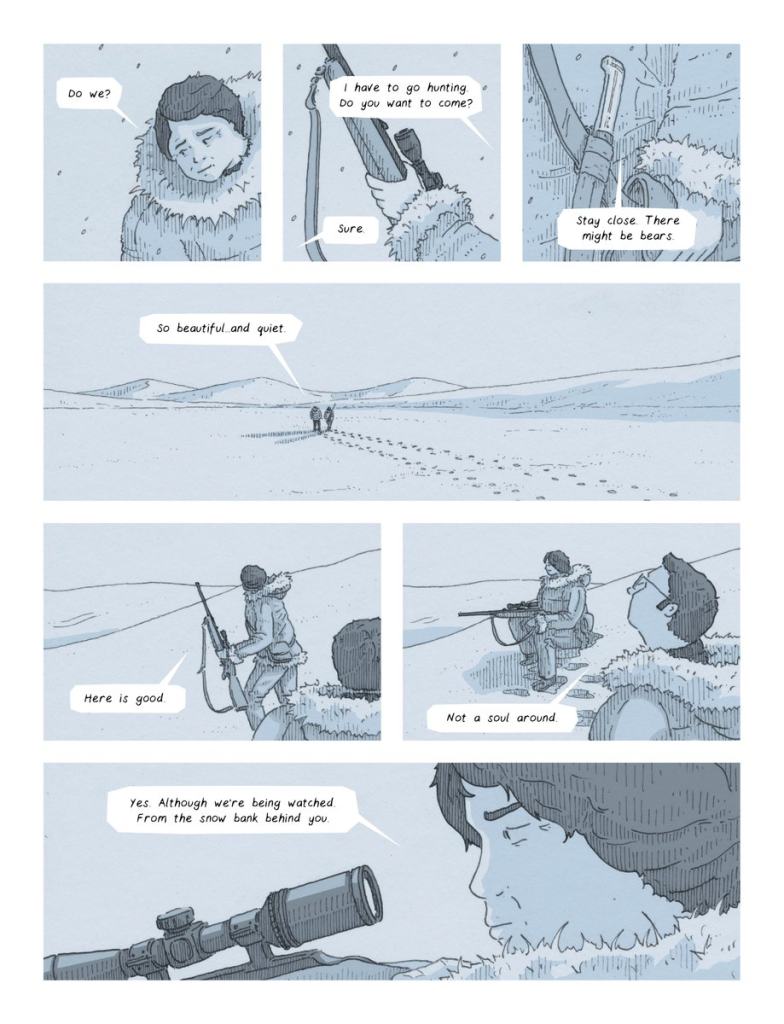

That cover tells you so much about the comic inside. The Union Jack pattern and the icebergs aren’t just a visual pun on the title, but also the first of many demonstrations of Owen D. Pomery’s beautiful sense of design and willingness to exploit the book’s engaging snowbound setting for all its metaphorical potential. Set in the 1980s, this psychological thriller follows Harrison Fleet, a British colonial officer sent to a remote outpost in the Arctic, where he feels increasingly threatened by the locals who still recall the atrocities committed in the early days of the settlement.

It’s colonialism as a vehicle for horror – although not so much the horror of the natives brutalized by the empire, but rather the horror of a man sent to the middle of nowhere, surrounded by hostile people and weather… and perhaps something more. You may not sympathize with Fleet’s mission and he’s certainly not the main victim here, but building the story around his estranged experience helps suggest some of the absurdity of colonialism, whereby a man without any connection to this community and territory wields a power granted to him by a faraway kingdom that has no consideration for anyone here.

A few flaws appear obvious. Most of the cast (especially the natives) are so underdeveloped that British Ice ends up reproducing a colonial outlook, as the locals remain a strange, scary Other and our sole source of identification is the western settler (for a more politically-conscious, less exploitative, and even more visually breathtaking take on this sort of subject, you can pick up Joe Sacco’s non-fiction graphic novel Paying the Land, which also came out last year). Genre-wise, though, the limited point of view and characterization convey Harrison Fleet’s sense of isolation and alienation, generating suspense along the way. In that sense, if anything the book should be blamed for not going deep enough into his psyche: there is some nice buildup early on, but on the whole the narrative feels too rushed to pack a proper wallop. I wanted more pages of Fleet struggling with the cold and the lack of resources. I wanted his creepy house to feel even creepier, like a haunted mansion. Hell, I wanted the whole island to feel like that!

A few flaws appear obvious. Most of the cast (especially the natives) are so underdeveloped that British Ice ends up reproducing a colonial outlook, as the locals remain a strange, scary Other and our sole source of identification is the western settler (for a more politically-conscious, less exploitative, and even more visually breathtaking take on this sort of subject, you can pick up Joe Sacco’s non-fiction graphic novel Paying the Land, which also came out last year). Genre-wise, though, the limited point of view and characterization convey Harrison Fleet’s sense of isolation and alienation, generating suspense along the way. In that sense, if anything the book should be blamed for not going deep enough into his psyche: there is some nice buildup early on, but on the whole the narrative feels too rushed to pack a proper wallop. I wanted more pages of Fleet struggling with the cold and the lack of resources. I wanted his creepy house to feel even creepier, like a haunted mansion. Hell, I wanted the whole island to feel like that!

To be fair, the tone Owen D. Pomery appears to be going for is cold and low-key all the way, from the cast’s understated background to the art’s sanitized minimalism, including a palette composed of different shades of grey. If you end up having to project a bit more than what the story gives you, I say it’s a low price to pay. An architectural illustrator, Pomery excels not only at the straight lines of man-made construction but also at the starkness of frozen nature, making the most out of negative space while creating expansive landscapes through the *absence* of drawing.

Plus, while the whole may not live up to the promise of the earlier pages, there are more than enough witty moments and details to make British Ice a worthy read. One of my favorites involves Fleet spotting a cross at the top of a mountain, only to be informed that it’s actually the tail of a crashed Russian aircraft (another character quips: ‘Certainly makes me keep the faith.’). Modernity and religion are thus reduced to a half-buried piece of scrap in what is just one of the many symbols, both subtle and flagrant, that populate the book, rewarding careful consideration of every exchange and visual choice.

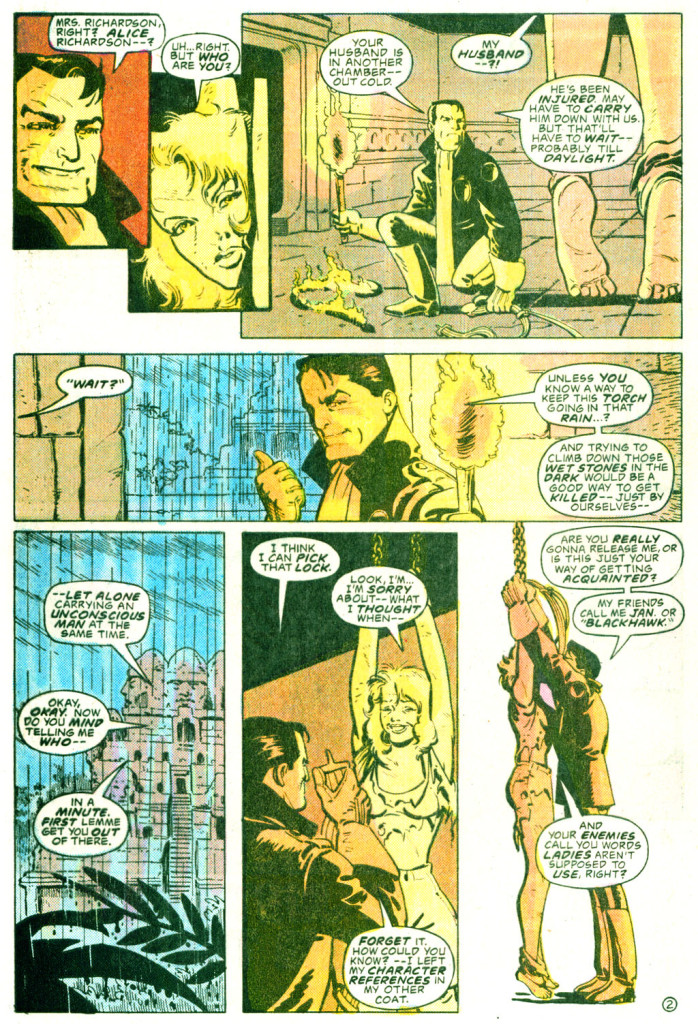

6. BLACKHAWK: BLOOD & IRON

This hardcover includes not only Howard Chaykin’s 1987 reboot of the classic war adventure series Blackhawk (which I believe may have been collected before), but also the (definitely previously uncollected) follow-up strip that came out in Action Comics Weekly in 1988 and a Secret Origins tale. If you don’t mind your anti-heroes smug and sometimes downright despicable, these are a bunch of fun two-fisted yarns packed with foreign intrigue and neat historical cameos.

This hardcover includes not only Howard Chaykin’s 1987 reboot of the classic war adventure series Blackhawk (which I believe may have been collected before), but also the (definitely previously uncollected) follow-up strip that came out in Action Comics Weekly in 1988 and a Secret Origins tale. If you don’t mind your anti-heroes smug and sometimes downright despicable, these are a bunch of fun two-fisted yarns packed with foreign intrigue and neat historical cameos.

I’m a huge fan of Chaykin’s mini-series, which throws pilot Janos Prohaska into an ultra-labyrinthine spy thriller in World War II, written and drawn in the kind of overwhelming maximalist style of Chaykin’s other masterpieces from this era (American Flagg! and The Shadow). Chaykin has a field day bringing in all sorts of groups that are often left out of the WWII public imaginary, from Jewish gangsters to American communists. He also interweaves layers upon layers of intertextual winks, playing with the franchise’s racist history (understandably, his Weng Chan doesn’t like being called ‘Chop Chop’) and modelling key players after actors Errol Flynn and Mary Astor (the later in the role of her character from 1941’s The Maltese Falcon… indeed, there are several references placing that film in the same continuity as this story!).

The plotting may be more confusing than your average comic, but I appreciate Chaykin’s willingness to take advantage of the medium’s potential – after all, although flipping through the book back and forth to pick up on certain threads makes for a less-than-fluid reading experience, the truth is that unpacking the various subplots provides its own type of entertainment. Plus, you can always just bask in the glorious visuals, especially as Steve Oliff does such a wonderful job with the colors… and, for the most part, so does Ken Bruzenak with the lettering, except for the terrible faux-Cyrillic font he uses for the Russians (which makes those sequences even more difficult to follow).

The big novelty for most people, I suspect, are the follow-up stories, written by Mike Grell and Martin Pasko, who embrace Chaykin’s caustic mix of sex and politics, even if Rick Burchett’s lovely artwork is more reminiscent of Milton Caniff (which doesn’t prevent Pablo Marcos, who inks some of the stories, from trying his best to ‘chaykinify’ Burchett’s pencils). Caniff is also a blatant influence on the scripts, which move the action to Southeast Asia, in 1947 (the year of Steve Canyon’s debut), where the Blackhawks, without a war, have fallen from grace and now spend their time gambling, drinking, brawling, and screwing prostitutes (there is great emphasis on the fact that they’re all horndogs, including the most tasteless cliffhanger I’ve ever seen, which misleadingly suggests the protagonist may be about to rape a tied-up woman).

These adventures, which take the Blackhawks from Burma to Indonesia and occupied Germany, all have an element of cloak & dagger, bringing to mind old Hollywood pictures like Robert Aldrich’s World for Ransom and Richard Thorpe’s Malaya. As for the Secret Origins tale (drawn by Grant Miehm and Terry Beatty in Burchett’s style), it wraps up loose ends from the Chaykin mini while elaborating on Prohaska’s communist background. Plus, it opens with a cute newsreel that does triple duty as a) exposition, b) Chaykin-esque pastiche of period propaganda, and c) a nod to Citizen Kane.

Finally, you also get a team-up set in 1988 between an older Weng Chan, Green Lantern, Black Canary, and Superman, but that comic (by Mark Verheiden and Eduardo Barreto) is by far the weakest of the bunch, serving more as a curiosity for aficionados than anything else.

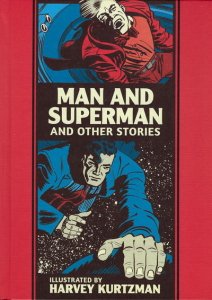

5. MAN AND SUPERMAN AND OTHER STORIES

No, despite the title, the misleading cover image, and the cheeky color choices, this is *not* a collection of Superman comics…

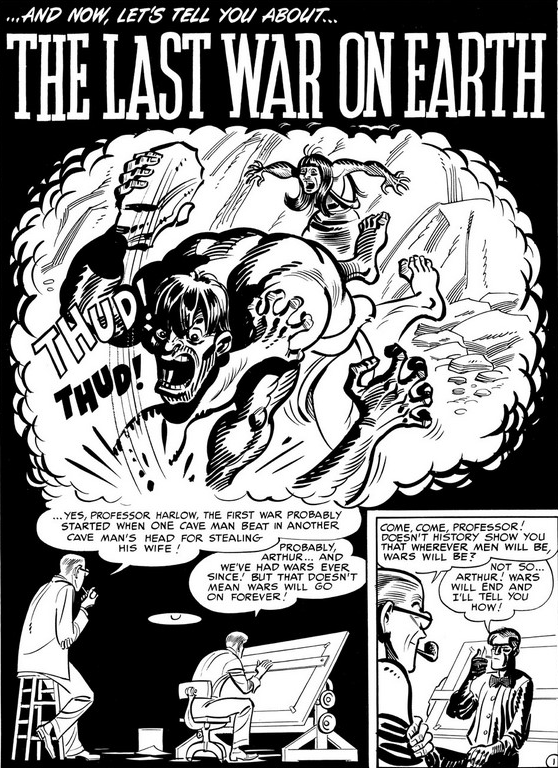

I’m a huge fan of Fantagraphics’ EC Artists Library series, which reprints classic EC comics in black & white and organized by artist, spotlighting their craft. The high point in the past year was this collection of Harvey Kurtzman’s work from 1950-1951. Before he went on to fully explore his comedic talent as writer, editor, and artist for Mad, Kurtzman bounced around other EC anthologies for a few years, lending his distinctively thick, cartoony style to short tales about bloody battles, ghostly hauntings, killers on the loose, or science run amok against the backdrop of the Cold War and of society’s growing mechanization… Having previously reprinted Kurtzman’s war stuff in Corpse on the Imjin! and Other Stories, Fantagraphics now gave us this collection of his horror, crime, and sci-fi tales. In other words, it gave us not only a bunch of darkly funny comics, but also the chance to learn about a lesser known phase in the career of one of pop culture’s most influential humorists.

Honestly, the only reason Man and Superman and Other Stories isn’t even closer to the top of this list is because the first handful of tales, scripted by other writers, suffer from rushed endings and underdeveloped plots (with the exception of ‘Lost in the Microcosm,’ penned by Al Feldstein, which is a gem). Once we get into the stories written and drawn by Kurtzman (which is most of the book), then things really start rolling, with practically one hit after another. His style is so lively and iconoclastic that the result almost feels like a parody of EC’s typical output. High points include ‘Atom Bomb Thief!’ (a knock-out spy adventure, complete with gunplay, a plane crash, and a shark attack), ‘The Mysterious Ray from Another Dimension!’ (a bonkers satire set in a future 1970 where ‘the skirts are now back to above the knee line’ and every person in the world watches television), and the titular ‘Man and Superman’ (a slapstick take on physical culture that doubles as a spoof of superhero bodies).

I’m not saying Harvey Kurtzman’s plots are highly original or outstanding just by themselves… What makes these comics so effective is that, more than an inspired writer, Kurtzman was a cartoonist genius, able to craft a zany, rhythmic interplay between art and words, grabbing your attention from the get-go before hitting you with a perfectly delivered punchline (usually a viciously ironic twist that mocked men’s self-importance and the futility of their plans). Unlike most EC stories, these ones actually feature silent panels and experimental layouts, as you can see Kurtzman playing around with the medium’s form (it also helps that many of the stories are hand-lettered, breaking away from EC’s standard mechanical lettering). ‘The Man Who Raced Time’ uses neat details to convey the impression of characters moving at very different speeds in the same panel. ‘Television Terror!’ is framed almost entirely by a TV screen, an especially innovative gesture considering that the story originally came out in 1950 (i.e., not only decades before The Dark Knight Returns popularized this technique, but years before television itself became a common household item). ‘Lucky Fights It Through’ (the oddest tale in the book, about a syphilitic cowboy) has as its centerspread a music sheet and lyrics for a Western Swing record.

As usual, the book comes with an informative introduction (by Thommy Burns) that provides background and/or analysis of the various stories and a final piece (by Steve Ringgenberg) about Harvey Kurtzman’s career. It also includes a curious two-fisted seafaring adventure tale that Kurtzman edited, written by his assistant Jerry DeFuccio and drawn by Joe Kubert.