First, a disclaimer: Rutu Modan’s latest graphic novel, Tunnels, has been translated to English and published by Drawn & Quarterly last year… and whenever a new Modan book comes out, the chances of it being my favorite comic of that year are pretty high. Alas, I still haven’t managed to get my hands on it, so let’s talk about some of the awesome comics I did read!

As 2021 raced towards the finish line, my choice for Gotham Calling’s book of the year kept switching back and forth. Even though, when push comes to shove, I tend to privilege compelling writing over innovative aesthetics, I was sure the top place was bound to look amazing, since we’ve gotten so many impressive examples of visual prowess throughout the year, from the Hedra-ish science fiction of EPHK’s Mawrth Valliis to the Afrofuturism-by-way-of-Tartakovsky of Juni Ba’s Djeliya, not to mention the ultra-dense tapestry of Barry Windsor-Smith’s Monsters. For a while, the best candidate was James Harren’s Ultramega: Stand with Humanity, which managed to unironically inject the kaiju genre with renewed vitality through smart, gutsy storytelling whose blood-splattered images are the quintessence of a certain branch of wacko post-apocalyptic/cosmic fantasy comics that flows straight to my pleasure centers…

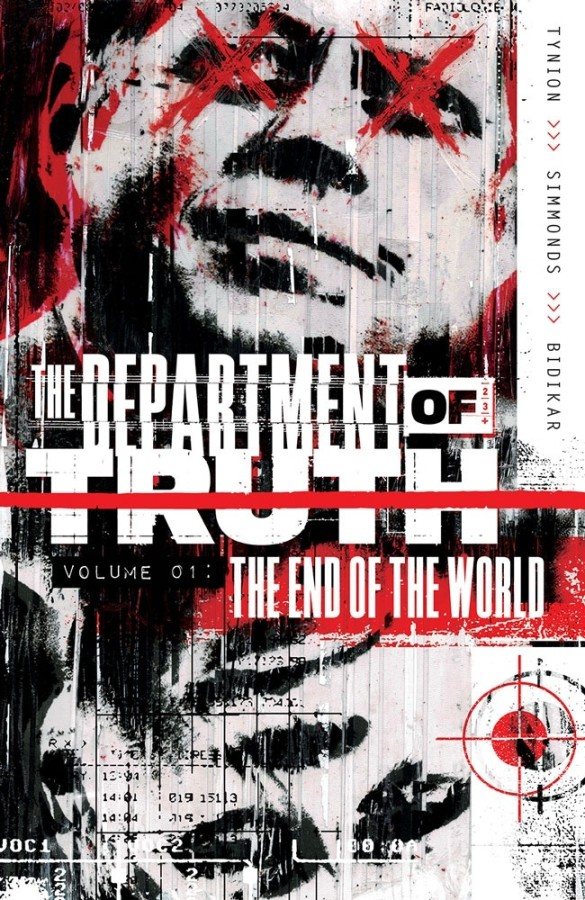

Looking back, though, despite the resonant subtext (about dealing with a deadly disease that can affect thousands of people around each infected person) and the jaw-dropping artwork (with jaw-dropping colors by Dave Stewart and jaw-dropping lettering by Rus Wooton), Ultramega’s epic romp couldn’t quite match The Department of Truth: The End of the World, which was the one book I ended up compulsively revisiting, recommending, discussing with friends, and mulling over more than any of my other reads.

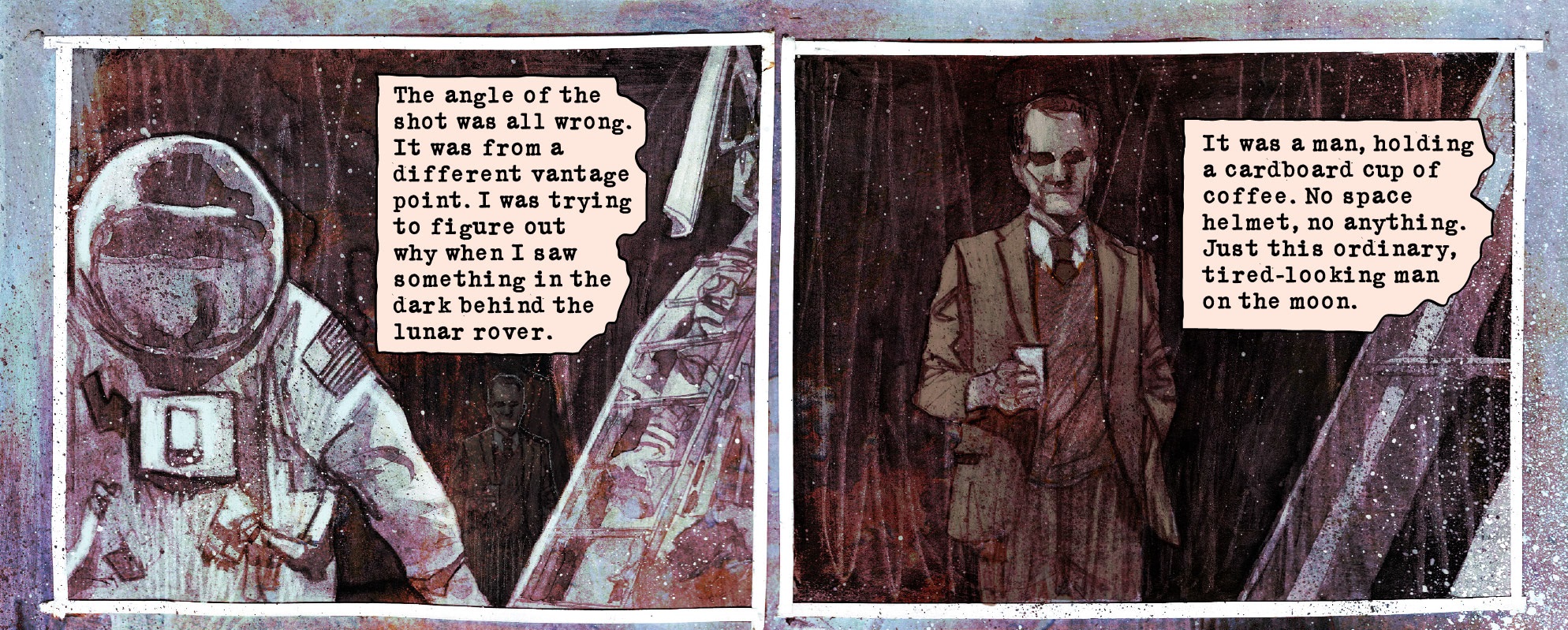

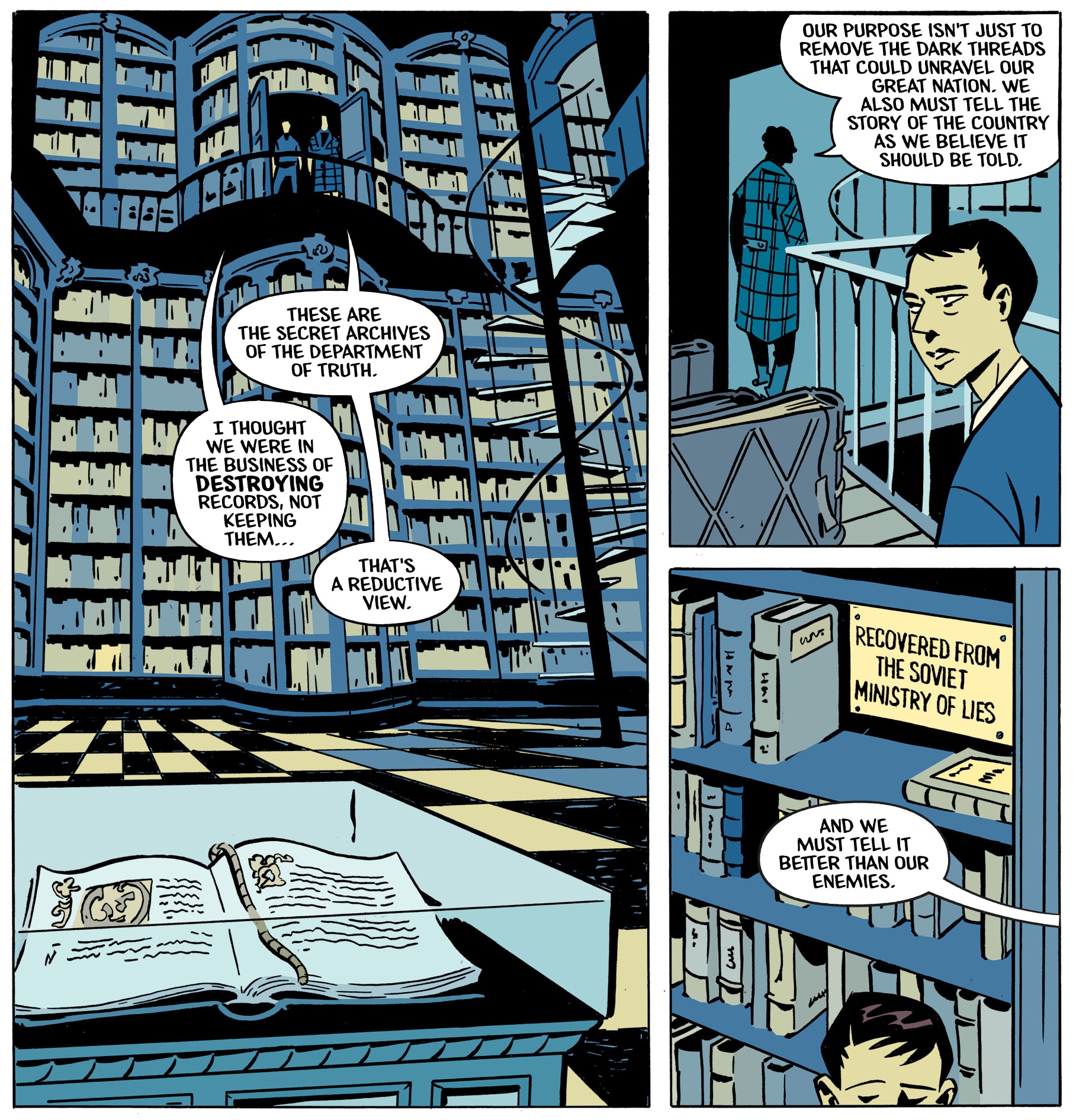

This paperback, published back in February, collects the first five issues of the ongoing series The Department of Truth, effectively establishing its captivating high concept: it turns out truth is literally a product of hegemonic consensus and it changes – on the material plane – according to what the majority of people believe, so the US government has set up the Department of Truth to prevent the spread of fake news from actually altering reality.

This notion raises so many intriguing questions that I can’t see the series running out of steam any time soon, as there is so much to explore… Before the scientific consensus over the earth’s shape or its position in the solar system, was the planet flat and static? If so, what was the basis to develop the current models of geography and astronomy? And does this mean that collectively denying climate change, rather than an irresponsible attitude with devastating consequences (because nature doesn’t care what you think), would turn out to be a solution to the problem, retroactively making it unreal?

On another level, should the materialization of mass delusions be considered the ultimate embodiment of democracy, a justification for faith-based wars, or an inspirational encouragement to will utopias into existence? And does this premise give the comic carte blanche to develop endless alternate timelines that have been wished out of existence, like a perpetual motion machine of speculative fiction (a subgenre I love so much that I had a blast watching For All Mankind, despite all the corniness)?

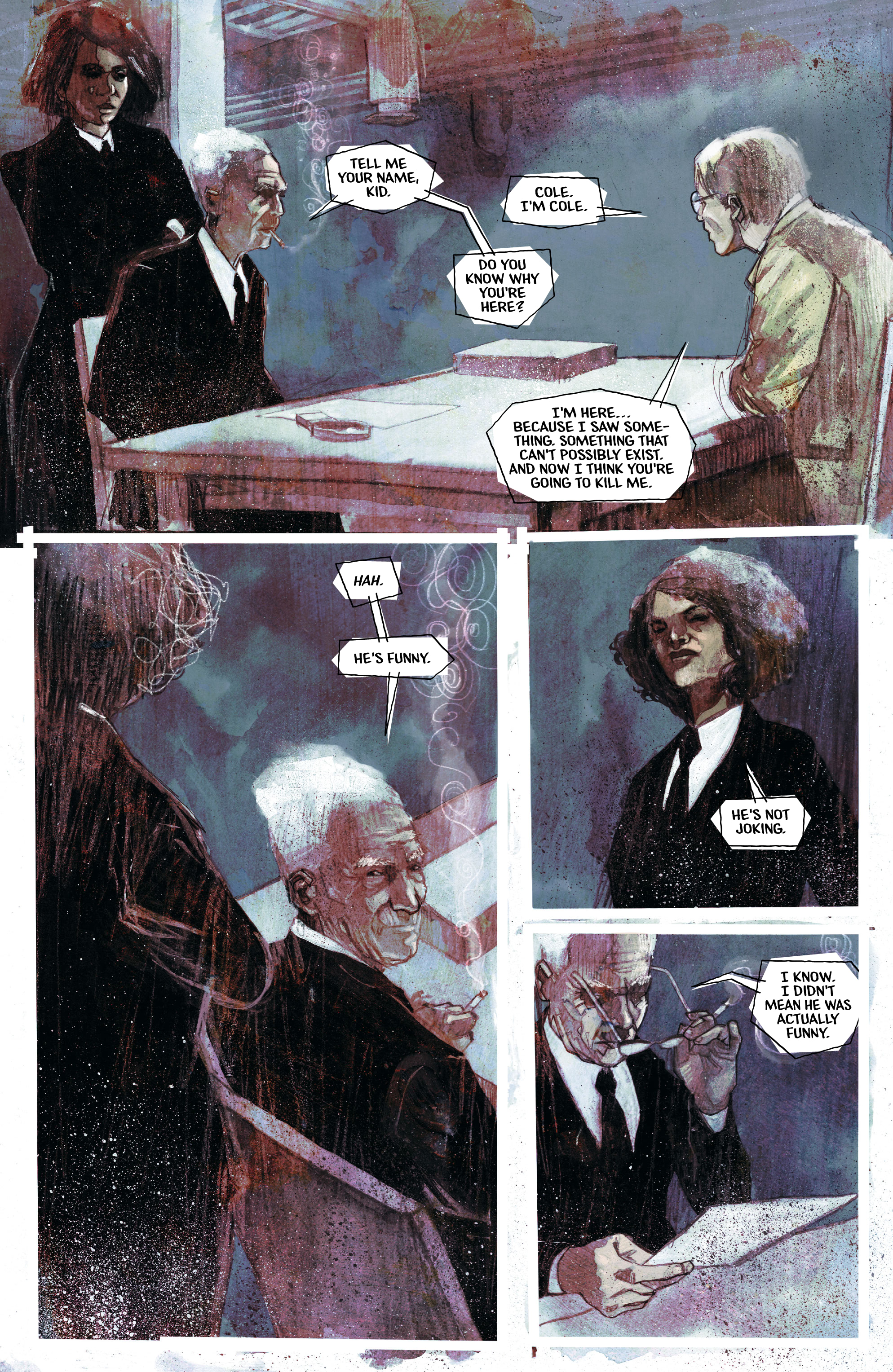

In a classic move, the series starts by following a newly recruited agent as he is introduced to this underworld, namely Cole Turner, a former FBI teacher specialized in online communities of right-wing white supremacists who now finds himself in an ironic position: he becomes part of what is essentially a deep state-ish organization secretly fighting a meta-conspiracy – going at least as far back as the Kennedy assassination – aimed at disseminating conspiracy theories. Predictably, it’s a matter of time before Turner starts wondering whether he is truly working for the forces of order and security or just for one of two sides locked in a lasting war for the determination of a dominant truth… After all, if facts are so subjective to the point that they can be radically overturned, that means he isn’t protecting reality itself, only a specific version of it. In other words, defending the established truth is inherently reactionary, since it reifies the status quo (including the existing power structure).

The same set-up could’ve led to something playfully surrealist or broadly satirical, but the approach is closer to Vertigo-style horror, which makes sense given where writer James Tynion IV comes from. The horror here is both of the supernatural kind and of a more psychological, paranoid strain, owing a clear debt to The X-Files yet pushing that show’s themes to the next level.

In fact, let’s get the references to other works out of the way. The result is more mind-bending than The Matrix, less absurdist than Men in Black, and more metafictional than JFK, albeit borrowing superficial elements from each of these. So far, it’s not as erudite as Umberto Eco’s dense novels about this sort of conspiratorial rabbit holes (most notably the phenomenal Foucault’s Pendulum, the horrifically gothic The Prague Cemetery, and the comparatively lighter Numero Zero), but its ambition keeps growing with every new issue.

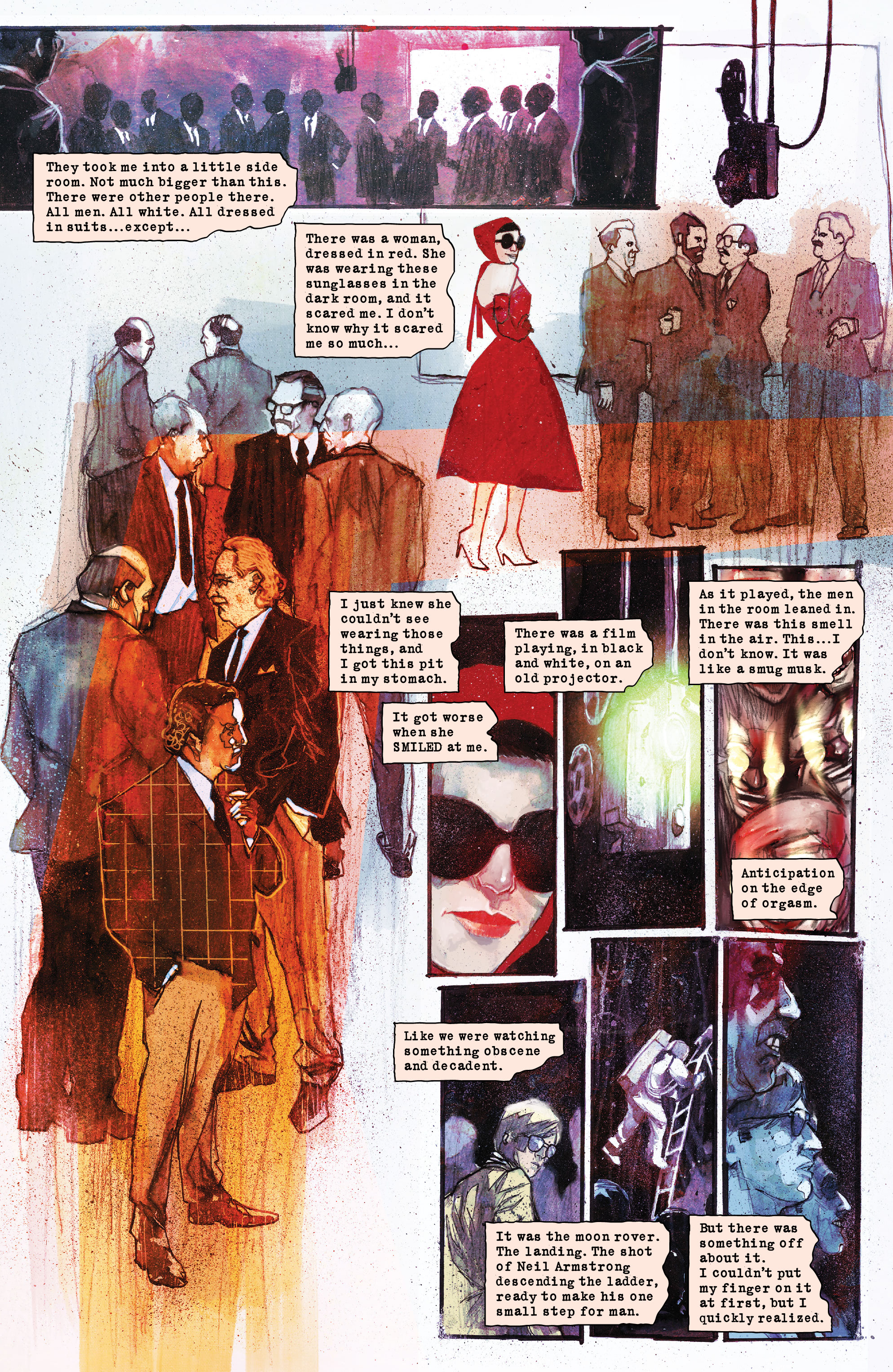

As far as comic books go, naturally I have to point out the Dark Knight’s neat contribution to this subgenre in the form of Conspiracy, written by Doug Moench (who is obsessed with this type of fringe theories and often wove them into his Batman comics). Provocative takes on the Kennedy shooting have quite a rich tradition, with memorable tales by Peter Milligan (in Shade, the Changing Man), Brian Azzarello (in 100 Bullets), Gerard Way (in The Umbrella Academy), John Ostrander (in Blackhawk), and Steven Grant (in Badlands). Although less creatively successful, 9/11 truther fiction has popped up in the medium as well, from Rick Veitch’s one-shot The Big Lie to the final volume of the Franco-Belgian black comedy/cop series Soda. Above all, though, I’d say The Department of Truth follows the path of Grant Morrison’s, Jonathan Hickman’s, and Warren Ellis’ many intricate spy-fi thrillers (picture a less unhinged update of The Filth or The Invisibles), with blatant visual echoes of Bill Sienkiewicz.

And yet, The Department of Truth: The End of the World manages to never feel like a mere recycling job, if nothing else because it’s so damn topical, tapping into the subjects of most of my conversations throughout 2021 while also feeding my interest in the complex workings of ideology and imagination. Not only does the book engage with post-truth populism, social media bubbles, coronavirus negationists, and QAnon’s collective text interpretation game, it links these ideas to older threads (like the 1980s’ satanic panic), historicizing them while dissecting their inner logics and perverse appeal. For instance, the third chapter is a twisted spin on Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina: it follows the harassed mother of the victim of a school shooting dealing with accusations that she’s a crisis actor participating in a false flag hoax… and the heartbreaking twist is that she gradually chooses to doubt her own memories because it’s more comforting to believe her son might be alive somehow.

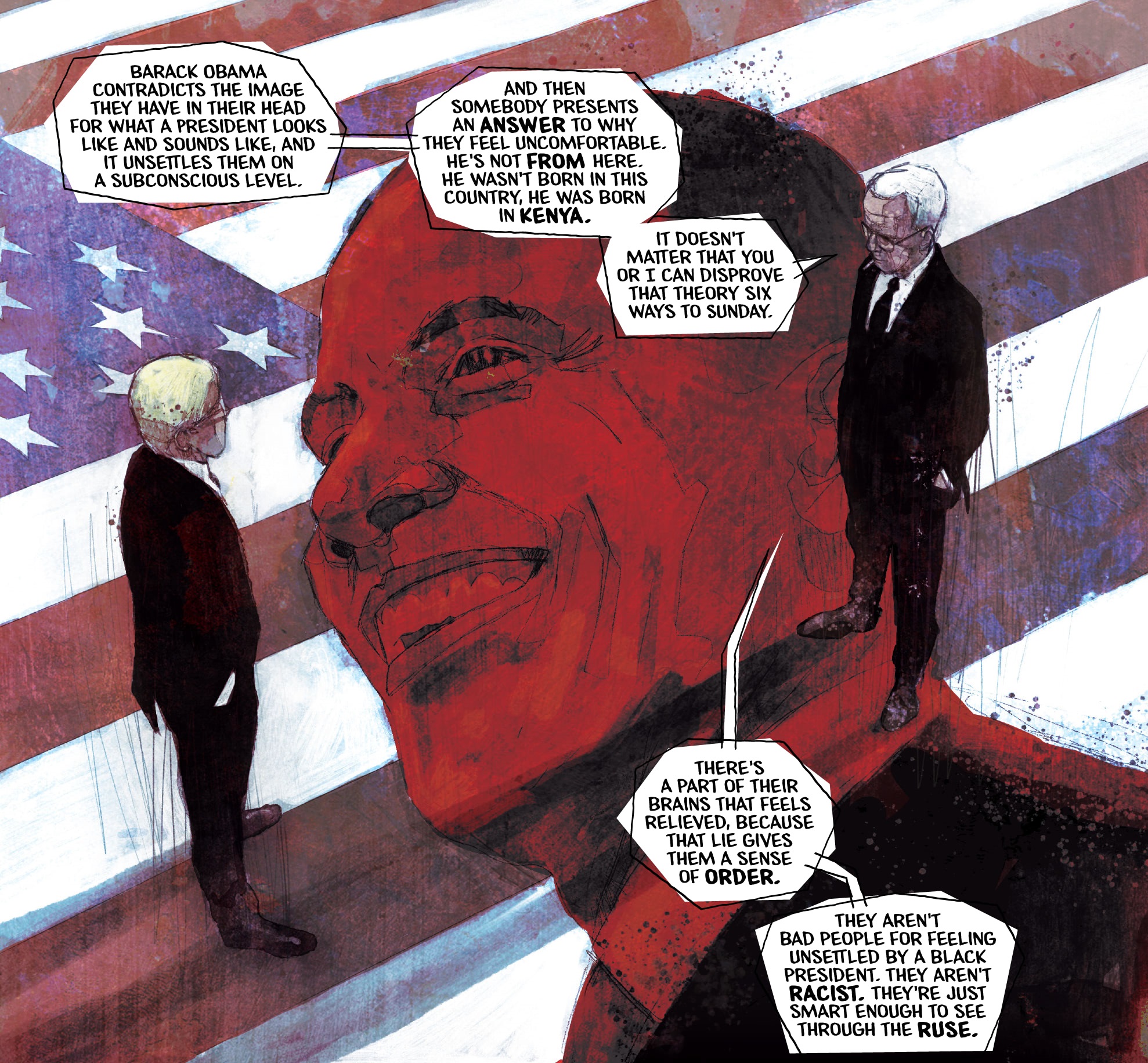

Indeed, more than dramatizing old debates about empiricist positivism versus postmodern relativism, The Department of Truth cleverly works thought-provoking readings of contemporary politics into its narrative. By treating belief as active rather than reactive (i.e. as creating rather than merely apprehending and reflecting an external world), the comic’s starting point appears to validate the crusaders against science (or, rather, against official science) while also presenting them as sinister, since their nightmarish fantasies stem for fear and prejudice. For example, at one point, the head of the Department of Truth insightfully argues that Pizzagate and Trumpism are logical extensions of the Birther Movement – if JFK’s assassination opened the door for skepticism about mainstream accounts of the truth, it was Obama’s election that pushed a vast section of the North-American population over the edge:

Between all these fascinating ideas and the sprawling scope of the story, Tynion’s scripts deserve praise for producing something that generally feels like more than an illustrated chain of exposition (although it does feel like that, at times). He keeps the cast’s dialogues and inner monologues snappy and cool, breaking them down into digestible chunks that generate a consistently gripping pace.

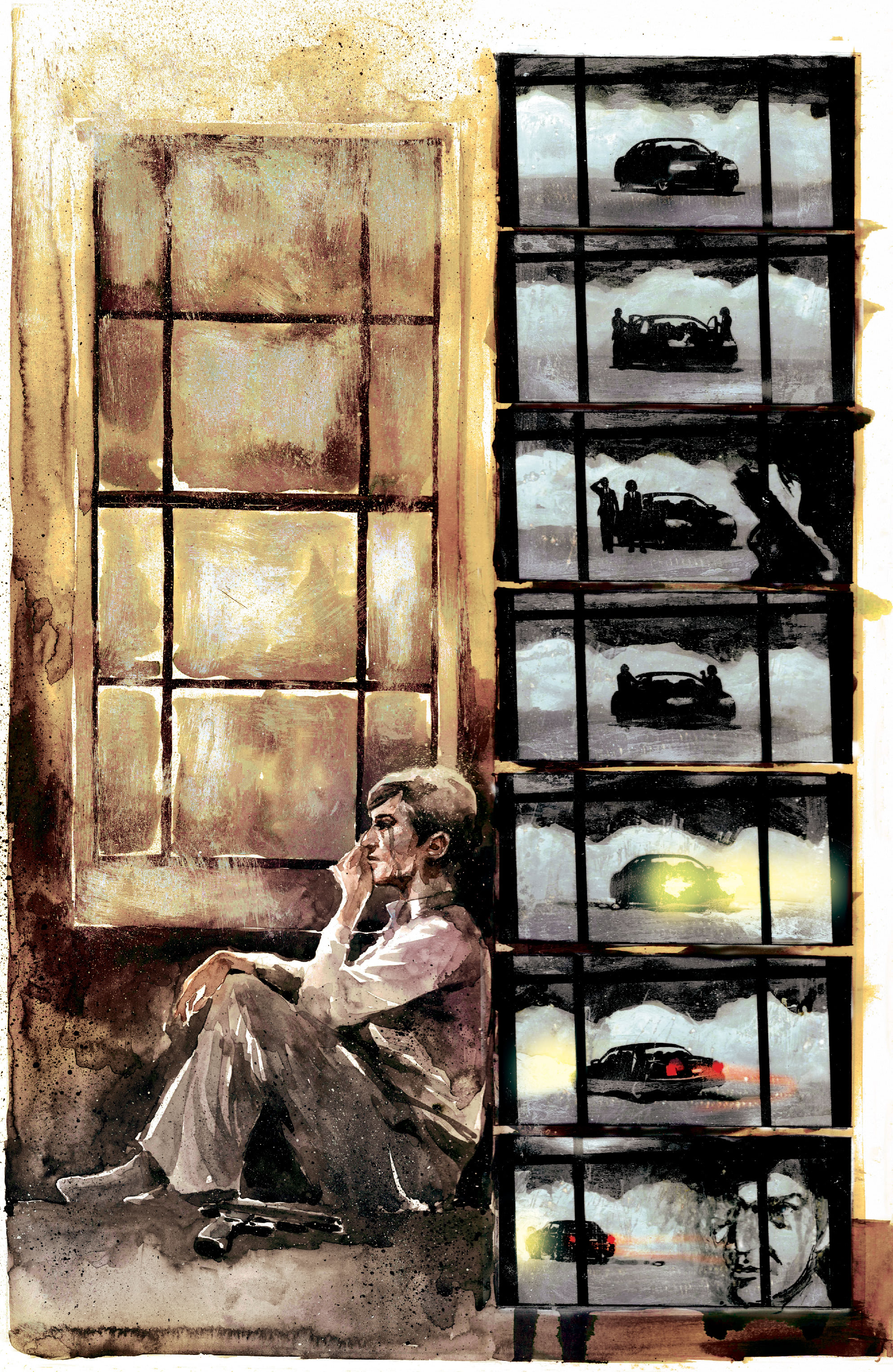

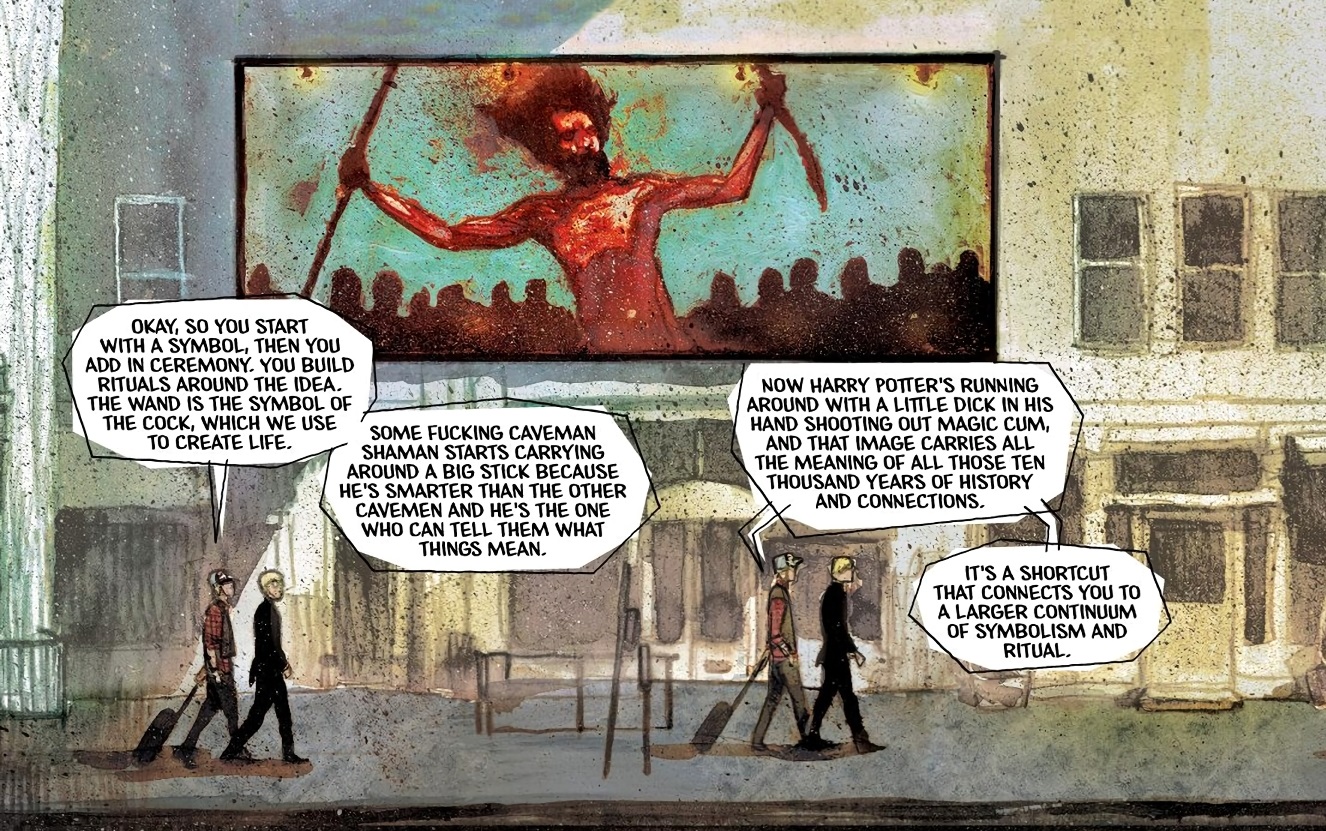

This task is crucially complemented by artist Martin Simmonds and designer Dylan Todd, who give each cover and page a strikingly original look, with collage-like visuals, loose watercolors, and constantly shifting layouts that invite you to get lost in (and later revisit) each scene. The backgrounds are just as likely to be abstract as to be figurative; they can be snapshots of what’s on people’s minds or even purely symbolic (in one of the less inspired choices, a double-spread juxtaposes the US flag with flying bullets and dollar bills, which isn’t exactly subtle!). Thematically, this lack of realism obviously suits the comic… The scratchy drawings and blurred figures literalize the notion of foggy, shadowy forces at play. The ink drips, the irregular coloring, and the imperfectly aligned shape of the word balloons around Aditya Bidikar’s letters all evoke the sense of a destabilized reality where everything is in flux and nothing fits naturally into its place.

I make it sound too conceptual and emotionally removed, but TDoT proves capable of delivering touching moments among all this chaos. Most notably, in the brilliant third issue there are several ‘silent’ passages depicting the loneliness and alienation of the grieving mother. One page just has her entering her home and switching on the light, somehow lending a powerful gravitas to this everyday gesture, as the gradually illuminated page channels the character’s own growing sense of safety from the dark world outside. A few pages later, the contrast between the light inside the house and the threatening silhouettes seen through the window is worked into this haunting sequence:

A second volume, titled The City Upon a Hill and collecting issues #8-13, came out in late October. It continued to explore the paradoxes that come from fighting lies through deception, using fiction to make people believe in reality, and protecting the truth by hiding truths. Along with the other independent series James Tynion IV has coming out at the moment (The Nice House on the Lake, Something is Killing the Children, and House of Slaughter), this book confirms he’s becoming one of the great masters of intelligent horror comics, simultaneously scaring readers and urging them to think about how their fears operate (this reflexive attitude towards the genre can also be seen in his Batman work, like the Clayface origin he did for Detective Comics Annual #1).

Indeed, besides giving more weight to cyberwarfare and twisty intrigue, The City Upon a Hill is quite focused on religion and magic (i.e., the art of manipulating ancient symbols) and a bit more prone to lengthy lectures, to the point that one of the chapters closely resembles the most esoteric issues of Promethea (I know I was supposedly done with the references to others works, but this one is pretty hard to dismiss).

What about issues #6-7? Those were a couple of flashbacks set in the Department’s archives, likewise written by Tynion but rendered in more conventional visual styles – despite some nifty pastiches – by the fill-in duos of, first, Elsa Charretier and Matt Hollingsworth (the artistic team behind the cool crime comic November) and, then, Tyler Boss and Roman Titov. These detours from the main narrative can be read out of sequence, so they’re bound to be collected later on.

Besides telling relatively standalone stories that are quite entertaining in their own right, such issues deepen the world-building, gradually filling us in about the weird history of TDoT’s universe. In doing so, they also assuage a complaint I had early on, which was that the series seemed too focused on the USA… After all, in this age of Russian bots and China viruses, I want to see The Department of Truth’s take on international cover-ups!

All in all, The Department of Truth is an imaginative distillation of all the reflections over the past years about how to make sense of the Trump administration’s embrace of alternative facts, the assault on the US Capitol, or the rise of an anti-vaccination movement in the middle of a pandemic. In fact, the series is so anchored in the current zeitgeist that I’m not sure how well it will age when looked at from the vantage point of the upcoming decade or so. Such timely resonance, however, is precisely what makes this Gotham Calling’s 2021 book of the year.