I read less comics than usual in 2022 – especially new stuff – so the pool for Gotham Calling’s book of the year was somewhat limited. Like last time, the one graphic novel that was bound to be the strongest contender proved trickier to get than I hoped… I’m referring to Emil Ferris’ much-awaited second volume of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, which I still haven’t been able to get but which will no doubt earn a write-up whenever I finally feast my eyes upon it (like it happened with the elusive Tunnels last year).

That said, it’s not as if there weren’t enough astonishing comics to choose from. The mind-bending series The Department of Truth ambitiously expanded its scope and experimentation in the latest volumes, so it once again proved to be an exceptionally stimulating read (between this and The Nice House on the Lake, James Tynion IV almost became the first writer to get the top spot on my list twice). And when I felt in the mood for more grounded storytelling, the ultra-atmospheric crime yarns of That Texas Blood grew into my most reliable monthly fix throughout 2022.

Meanwhile, a bunch of longtime creators returned to their deservedly acclaimed masterworks, from decades ago, and – for the most part – managed to provide worthy follow-ups. Most notably, Bryan Talbot’s The Legend of Luther Arkwright revisited the multiversal political intrigue of the titular telepath’s bizarre saga – and, while the tapestry of interconnected narratives feels messier this time around (one strand does little more than recount events from the previous books; another gets stuck in morally simplistic territory about good & bad people), these are minor side effects of how incredibly ambitious, personal, and maximalist the whole project turned out to be.

That said, my favorite book of 2022 – and the one that most vividly reignited the sheer joy I can get from genre comics – was Catwoman: Lonely City.

Written, drawn, colored, and lettered by Cliff Chiang – who also provided the sublime covers – Catwoman: Lonely City collects a clever, prestige-sized, stupendous-looking mini-series set in a near future where Batman has died and an ageing Selina ‘Catwoman’ Kyle has been in jail for a decade. Finally released, she encounters a gentrified Gotham – ‘cleaner, safer, and a lot less free’ – whose mayor, Harvey Dent (formerly Two-Face), has cracked down on caped vigilantes and outlawed all civilian masks (including Halloween costumes, which is oddly literal).

Following a classic formula, Selina then tries to put together a crew of misfits for one last score, albeit in a police state where armed ‘tactical officers’ patrol the streets wearing Batman uniforms and the Dark Knight’s technology has been put in the service of mass surveillance. (It gets weirder.)

Batman comics are usually not a good way to predict the future (even if in 2003’s Gotham Knights #42 a virus did mutate from bats to humans, almost killing Alfred as a result), but they tend to provide an entertainingly distorted image of the present. True to form, Lonely City doesn’t feel like it’s set in the day after tomorrow as much as in another version of today:

It’s hard not to see in this tale of an older (anti-)hero coming back from retirement, set in a somewhat satirical dystopia,a response to Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns. Other comics have followed Miller’s footsteps – most notably Old Man Logan – although Lonely City’s intertextuality stands out, not just because of the direct formal echoes (such as the exposition conveyed through rows of panels simulating TV screens), but also because of Catwoman’s own status… This is yet another alternative Gotham, but instead of DKR’s fantasies about macho vigilante justice against street criminals (which relegated Selina to a minor role as a beat-up sex worker), it’s framed from the perspective of an outlaw woman fighting against an oppressive system (with a mostly absent Batman).

They’re both libertarian fables, in a way, but while 1980s’ Miller caricatured social collapse and a foreign policy heading for nuclear war, 21st-century Chiang focuses on urban segregation and on authoritarian domestic control, from privacy intrusion to a militarized police force. The ironic twist is that, by having the cops employ the Dark Knight’s symbols and tech, this Gotham City comes off like an extrapolation of DKR’s own fascistic undertones…

And, to be sure, in the end it turns out the main thing Catwoman rebels against is the very desire to prolong Batman’s legacy in whatever twisted form. You can love something and move on. There are other stories to tell.

Without ever going fully meta, the result is nevertheless self-reflexive and, in places, arguably deconstructive. The blurb on the back cover claims that ‘Gotham has grown up – it’s put away costumed heroism and villainy as childish things.’ Yet Lonely City seems less interested in commenting about The Dark Knight Returns than in finding its own place in the house Frank Miller built.

Indeed, just as Miller played with readers’ awareness of the Adam West television show, so does Cliff Chiang play with awareness of Miller’s work. And not just DKR, either. Batman: Year One – which rebooted Catwoman as well – casts as much of a shadow, with plenty of riffs on that classic in both the visuals and the dialogue (as pointed out in this review), down to the final scene.

In fact, Lonely City is full of nods all around, with Chiang using not only the story (future Gotham is its own subgenre, including such gems as Batman: Year 100), but also the designs, the lettering, and the colors to evoke the franchise’s different eras, ranging from Richmond Lewis’ washed-out palette in Year One down to Wildstorm FX’s quasi-monochrome compositions around the turn of the millennium…

Detective Comics #743

It’s to the book’s credit that the whole thing feels quite coherent. All these references are filtered through Cliff Chiang’s own distinctive art style, avoiding full-of pastiches, and the homages generally don’t call too much attention to themselves, nor will they get in the way of those who don’t recognize every deep cut.

This negotiation between suggesting a larger history on one level while still communicating story and characterization in a more direct fashion is one of the series’ major strengths. In control over the various elements of the whole process (script, art, colors, letters), Chiang seems to always know which one is conveying the bulk of emotion and/or information, so he strategically ‘mutes’ the others so as not to unnecessarily overwhelm the reader, thus mining the medium’s potential for all its worth.

Although comic books share features of novels and films, they don’t fully mimic either of them, as they’re not as text-heavy as novels and they certainly don’t display as many images as a film. This is for the best: a medium’s boundaries and limitations can be stimulating in their own way, giving us more room for imagination (in the case of comics, this starts, of course, with our constant interpretation of what happened between each panel or how each character’s voice sounds like). It’s why I tend to prefer this type of artwork and colors, which do not look ‘realistic’ – the adjustment process in my brain is a source of pleasure, asking me to engage more actively with the book and ultimately be more of a participant (even a co-creator) in the storytelling process. In reading and rereading Lonely City, I kept feeling Chiang engrossingly pulling me in, inviting me to give life to his stylized figures and to fill in the ellipses not just between the images, but in the cast’s insinuated backstories (by drawing on my own repository of memories of previous adventures, combined with a healthy dose of speculation).

I suppose Lonely City operates in something like Grant Morrison’s hyper-continuity, blending into the same unified past all the previous Batman comics, no matter how inconsistent in narrative and tone (especially if you go back to the earliest days…). This means that all the coolest tales did take place, somehow, including the many variations of the history of Selina Kyle, who over the years has been a burglar, a prostitute, and a crimefighter. Through backdrop props and flashbacks, Chiang thus gets to draw Catwoman’s various costumes, whether from the Golden Age or from Jim Balent’s and Darwyn Cooke’s iconic runs.

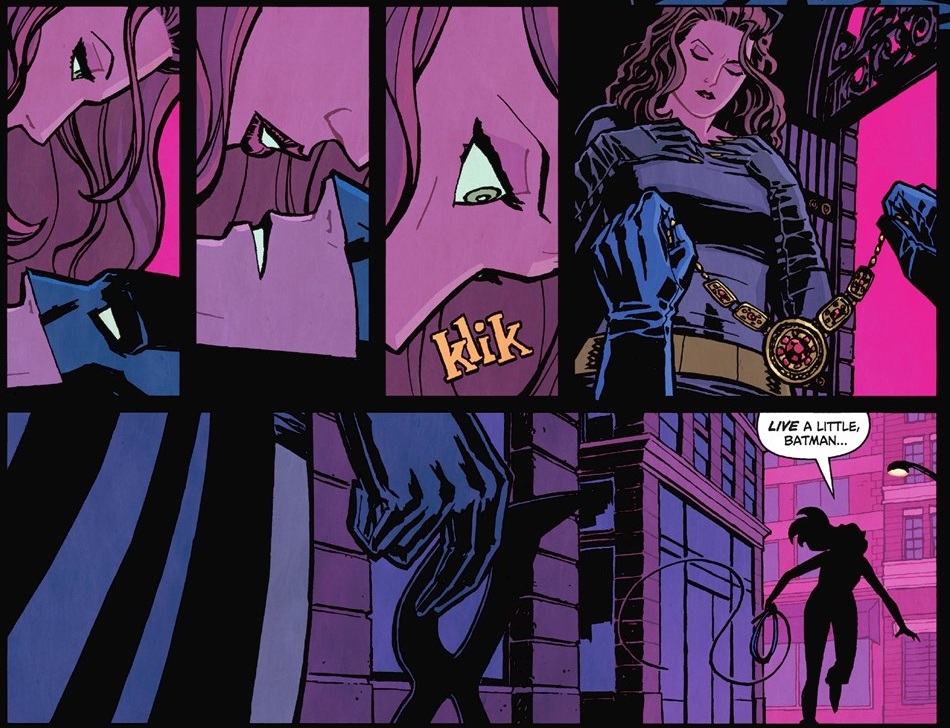

One of the most memorable sequences beautifully brings together the sexy aesthetics, playfulness, and elegance of the character’s most famous TV iterations, in the 1960s’ show and in the 1990s’ Batman: The Animated Series (and its many-spin-offs):

These winks, along with the countless Easter Eggs and more substantial appearances by familiar faces and places (I’m sure that, as I write this, someone is already working on an annotated guide!), could’ve devolved into facile fan-service or intricate metafiction, a la Donny Cates’ and Geoff Shaw’s Crossover. Beyond all the geekgasms, however, there is enough plot and action to hold one’s attention – like in many of the greatest Batman narratives, the intrigue concerns city politics, and like in many of the greatest Catwoman adventures, there is a string of neat capers, each one a dynamic set piece on its own. The smooth panel transitions and page layouts make this the most exciting heist book I’ve read since Stray Bullets: Sunshine & Roses.

Still, DC veterans are bound to get a special kick out of this one. After riffing on DKR, Lonely City moves into Dark Knight Strikes Again territory, digging up colorful characters and concepts from across the wider DC lore, way beyond the Gotham corner of this universe. At first, the inclusions tie into the general motif of rampant capitalism and commodification, whether it’s the spy agency Checkmate having been turned into a private security contractor or – as you can see from the Captain Cold Brew in the initial scan – the running gag about superhero/villain names being converted into brand logos (which implies that, within this reality, perhaps some of the old heroes and villains actually endorsed these products and are now living off the royalties).

By the time we get to the Zatanna cameo (not to mention the climactic demon swordfight), though, Lonely City – for all its revisionist touches – has become a pure superhero yarn… one where minor plot points don’t necessarily derive from elements that have been set up in this particular story, but from elements that old-school fans may know because they’ve encountered them before in other comics (or, at this stage, perhaps in a handful of movies and streaming shows). But what can I say: as one of those fans, I can’t deny the awesomeness of seeing Selina Kyle shoot a weaponized umbrella against a canister of Scarecrow gas.

That said, if part of the allure is to find out what happened to all those members of the Rogues’ Gallery, finally giving them closure in a post-Batman world, a lifetime of investment in this cast means the payoff can be particularly funny, interesting, and even emotional.

The sexual allusion above isn’t just Cliff Chiang making the most out of DC’s Black Label permissiveness. As a self-conscious comic about an older Catwoman (who, in the past, has exploited, indulged, and emancipated herself from bondage), Lonely City deals with sexism and agism and other forms of discrimination, even if it’s not ostentatious about it.

Chiang redesigns characters’ bodies to show how they’ve aged in a variety of ways, from getting wrinkles to putting on weight. He also expands the overall ethnic diversity, including through an Asian shopkeeper called OGBeast (an amusing spin on the KGBeast) that I’ve little doubt is here to stay.

As age becomes a core theme – along with grief and nostalgia – Lonely City pulls off an impressive multilayered balancing act. On the one hand, it uses the weight of the franchise’s accumulated history to conjure up deep resonance in older readers like me… After all, there is also a sentimental side to geekiness, informed as it is by an urge to maintain a personal, individualized relation to the mass culture we consume. On the other hand, a series of endearingly rendered character moments manage to bring these specific iterations to life with almost unprecedented clarity and melancholy, thanks to Chiang’s abovementioned command of the form and an especially insightful take on their possible psychologies.

After all these years of reading and blogging about them, watching Catwoman and the Riddler reminisce about their past, I felt as if, in a magical way, I was gazing into to their true selves, finding in these people (and in this comic) something both recognizable and surprising at the same time.