Before delving into Gotham Calling’s pick for book of the year, I tend to briefly highlight comics that didn’t earn such dubious title because, although awesome in their own way, they’re too distant from the kind of genre narratives this blog focuses on. In 2023, it’s the case of Sammy Harkham’s Blood of the Virgin, a moving, disenchanted look at the fringes of the film industry in early 1970s’ Los Angeles, mostly seen through the eyes of a B-movie editor-turned-writer-turned-director and his frustrated wife.

Sure, while not a genre book, this is to some degree a book about genre – not so much about the specific subgenre of gothic horror period pieces like the titular picture, but about something that’s arguably now seen as a genre in itself, namely the exploitation schlock churned out on a shoestring budget for the grindhouse theatres and drive-in circuit whose frantic production schedules and offbeat cost-saving solutions have become part of their recognizable charm (even if Blood of the Virgin makes Paul Maslansky’s Sugar Hill or Jack Hill’s The Big Bird Cage seem like big productions in comparison). That said, what makes this such a remarkable graphic novel is how far it expands beyond this milieu, lingering on the equally demanding toll of raising a baby, fleshing out flawed, multifaceted characters, capturing the outlook of a certain immigrant experience, and – in a particularly memorable chapter – somehow developing a smooth link that goes from the persecution of Jews in 1940s’ Hungary all the way to the heartbreak of a young biker thirty years later, in New Zealand.

And yet, even had I disregarded labels, my choice of favorite book this year would still end up where it did:

What if instead of one genie in one lamp granting Aladdin three wishes, there was a whole industry of licensed containers with magical wishes (technically spells) being sold and regulated? This was the quirky starting point for a brilliant trilogy of Egyptian comics that came out between 2015 and 2022, focusing on interconnected Cairo-based characters trying to purchase, formulate, or offer such wishes. This year, the comics were collected in a chunky omnibus translated into English by the author herself, Deena Mohamed, and published by Granta Books as Your Wish Is My Command (the edition I own) and by Penguin Random House under the original title, Shubeik Lubeik.

Mohamed gets a lot of mileage out of this modern fairytale premise, imagining how different types of people would use and engage with the wishes in different ways: hospitals develop magic-based medicine, universities offer Wish Studies degrees, the rich create invisible gated communities, the UN Security Council discusses peace-related wishes… There is plenty of dark humor along the way (the opening advert seems straight out of RoboCop), particularly around the notion that the wishes being traded range from powerful and reliable first-class wishes to cheap, crappy third-class wishes that often misinterpret what people actually want, Monkey Paw-style.

It’s a smart piece of speculative fiction, exploring the emotional, political, theological, and logistical implications of the commodification of supernatural wishes against the backdrop of industrial capitalism and imperialist extractivism, especially in the Middle East.

There is a blatant allegory about access to natural and economic resources in Shubeik Lubeik, but Deena Mohamed develops this alternate reality beyond narrow metaphors. For all the satirical jabs at Egypt’s class system, bureaucracy, and colonial legacy, Mohamed lets the themes emerge organically from logical deductions about how such a world would evolve. Of course there would be a whole field of philosophy theorizing about desire (hell, there already is one anyway, even without magic). And does anyone doubt there’d be abolitionists concerned with either the ethics of the users or the conditions of the djinns? It’s also not a big leap to assume governments and wealthy elites – and Global North countries – would end up monopolizing the best wishes.

A big part of the appeal is how the book grounds the fantasy into a recognizable portrait of our own world, in particular Mohamed’s authentic-looking depiction of Egyptian history and society.

Despite the high concept and elaborate world-building – expanded through amusing infographics in the interludes between chapters – what makes Shubeik Lubeik such an impactful read is how rich and diverse the core stories are, digging deep into the cast’s experiences and complex emotions while dramatizing larger themes. By zooming in on the specific challenges of fleshed out individuals dealing with this fantastical device, the book matches – and even surpasses – the humanist magic realism of other acclaimed comics, like Daytripper or The Many Deaths of Laila Starr.

Every chapter is rendered in high-contrast black & white, with a colorful framing sequence, but because Deena Mohamed is an ambitious artist as well as an accomplished fabulist, she draws each tale in a distinctive style, satisfyingly adjusting the rhythm, tone, and aesthetics to the subject matter.

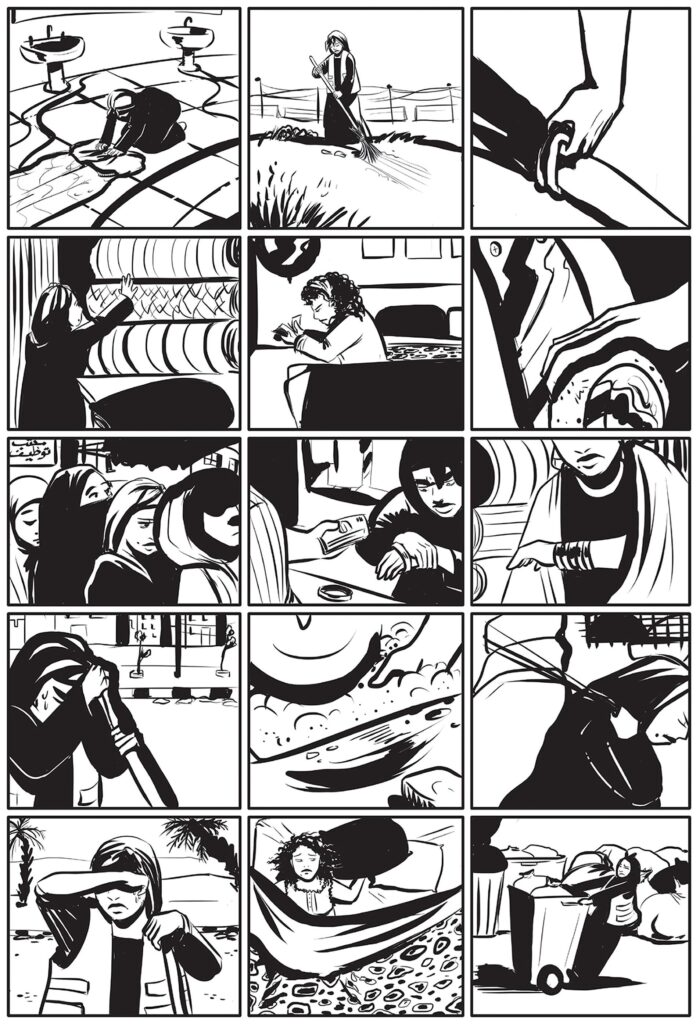

The first of the three stories, set in a working-class context, follows the long-suffering Aziza, whose husband – possibly inspired by Janis Joplin – keeps wishing for a Mercedes. It’s a touching look at couple dynamics, but it also morphs into a harrowing saga about how there is only so much magic can do against poverty, red tape, and police repression. Mohamed adopts an increasingly expressionist style, including a number of minimalistic compositions that take over the pages, making them feel viscerally oppressive and laden with poignant symbolism.

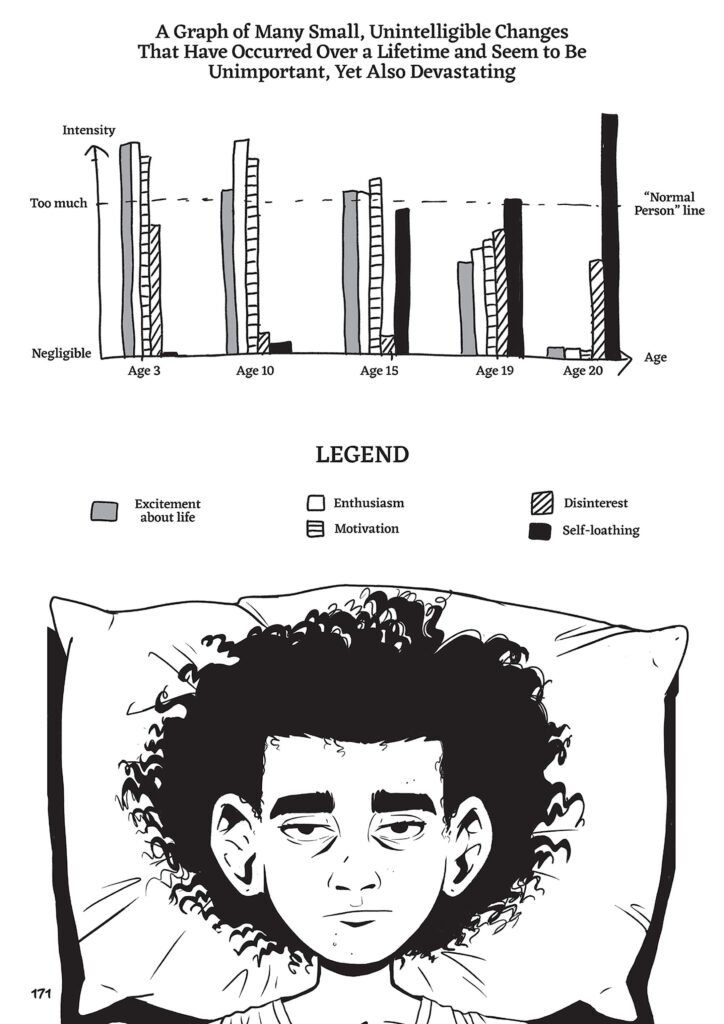

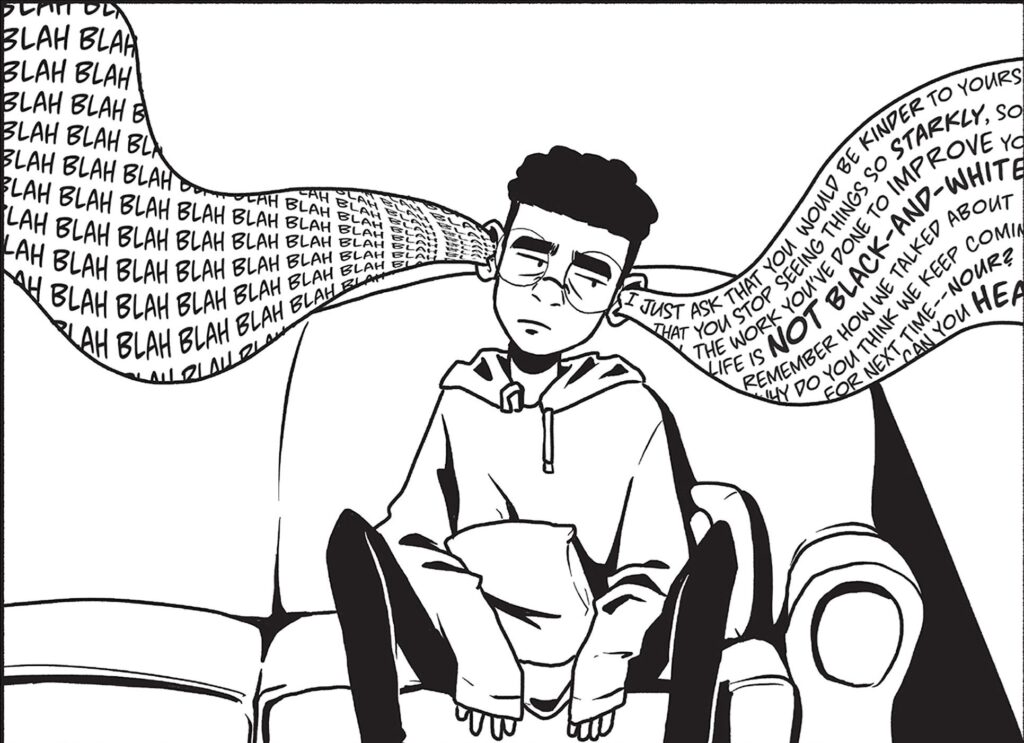

If the first chapter revolves around systemic social issues, the second one feels more inward-looking, shifting the setting to the upper class while going on a lengthy journey into a student’s mental health problems. Suitably, the artwork here is much more experimental, as instead of external actions the main focus is now on the inner workings of the mind:

This chapter’s protagonist, Nour, is a privileged kid of ambiguous gender (probably non-binary, I suppose) struggling with depression. Mohamed touches on the disease’s various dimensions and conflicting interpretations of how to tackle it, but she doesn’t let Shubeik Lubkeik become a mere awareness-raising text. Rather, those dimensions and interpretations consistently inform Nour’s sinuous process of figuring out what to wish for, how to word it, and whether they actually should/deserve to use a wish at all.

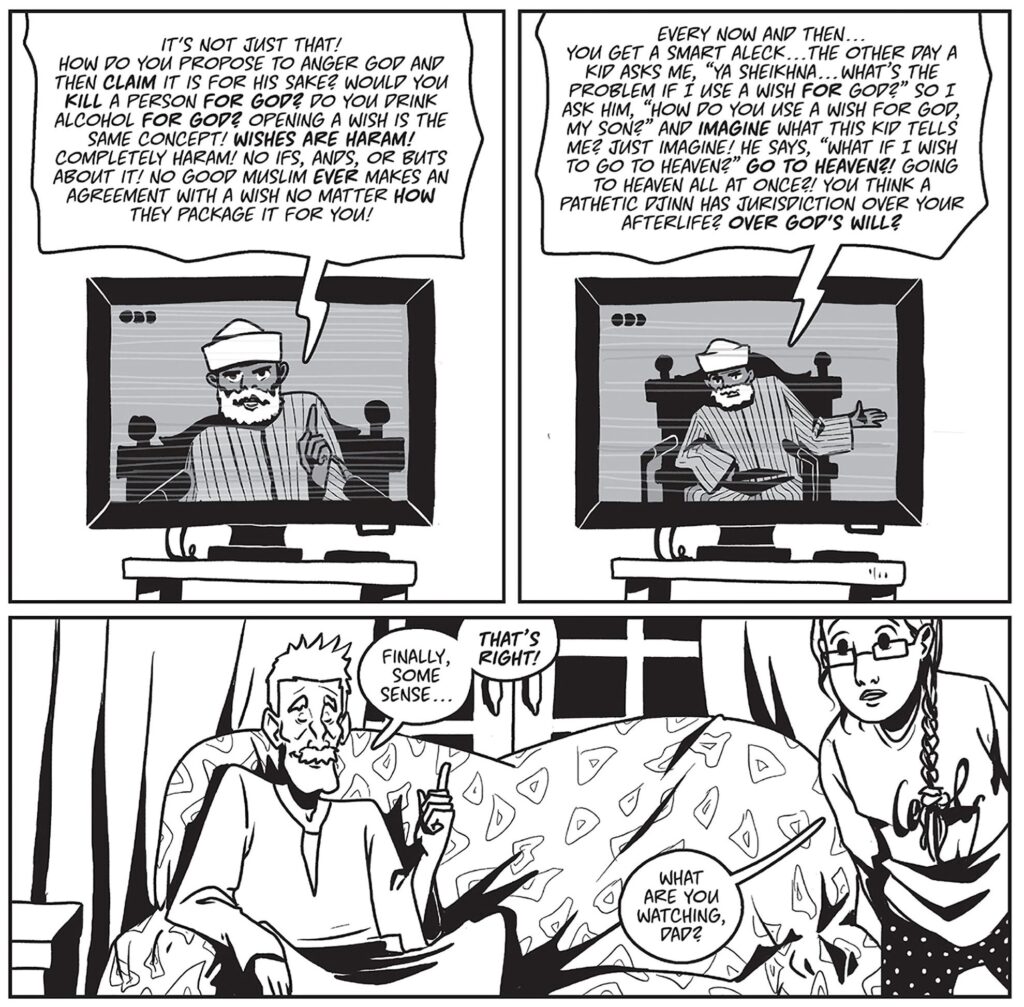

The third tale is the least linear of the lot (delightfully so). It mostly deals with religion, namely by following the soul-searching quest of Shokry, a wish-seller who also happens to be a devout Muslim… and who therefore has to reconcile his actions and intentions with the fact that traditional Islam is opposed to supernatural wishes. His guilt and doubts grow particularly unbearable when a person he cares for becomes terminally ill, making him question his convictions and belief system. The narrative eventually drifts into some pretty unexpected places (there is an awesome story within the story, drawn in yet another style), although not before we get a closer look at the cultural diversity that can be found across Egypt…

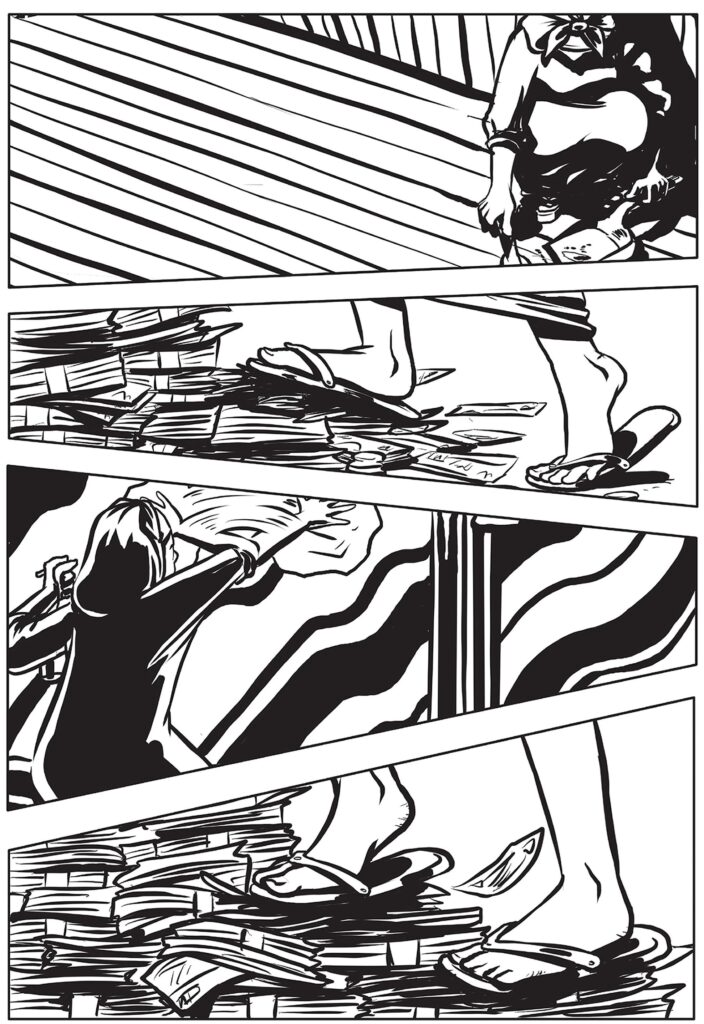

If you found the panels above a bit confusing, it may be because you read them in the wrong order. Shubeik Lubeik was originally conceived and published in Arabic, which is read from right to left, and the foreign editions stick to this sequence. It’s interesting because Deena Mohamed noticeably put a lot of care into the translation, making the book as accessible as possible to an English-reading western audience, including idiomatic expressions (sometimes jarringly so, as it can occasionally ring awkward to see these characters saying they’re ‘fit as a fiddle’) and even sporadic footnotes contextualizing culturally specific phrases and customs. Nevertheless, she decided to preserve the drawings’ fluidity and thoughtfully constructed layouts by keeping the pages’ overall organization.

This won’t be a big deal for those used to manga books published in the same format, but I’m not one of those, so at first I felt a bit disoriented (even when turning a page the other way around, my eye instinctively traveled to the upper-left corners). Yet, not only did I get used to it after a bit, but it somehow made the reading experience even more special and original. Sure, I realize Mohamed was just drawing the way all other artists draw in her part of the world (and in other regions, like Japan), but the choice not to flip the pages for the western editions is formally daring, making Shubeik Lubeik stand out in this publishing context… Of course, it helps that Mohamed’s storytelling is generally pretty tight and clear:

(Did you notice the kid with the three eyes? He’s clearly the result of a third-rate wish gone wrong, but he remains an extra who only shows up in these two panels, so whatever happened to him remains up to our imagination… The book is full of such intriguing details.)

Shubeik Lubeik may be Deena Mohamed’s debut graphic novel (on the heels of doing a popular webcomic about an Egyptian superhero), but she proves herself as a force to be reckoned with. In addition to a stark command of pacing, a knack for expressive cartooning, and the enviable precision of her thick lines and dark inks – especially in the monochrome chapters – Mohamed has a way of making the most out of negative space, resulting in some unforgettable splashes.

I can’t claim to spot all of Deena Mohamed’s influences, but manga and US comics are surely among them – the former most prominently in the hair-raising action scenes; the latter, for example, in the strategic use of insets and close-ups.

While borrowing ingredients from different traditions, however, Shubeik Lubeik never looks like a mere pastiche, not least because Mohamed keeps switching things around. It’s rare for more than three or four consecutive pages to share an overall design. If one page has a European-style 9-panel grid, then the next one may have a bunch of horizontal strips, or perhaps vertical panels, or offer a large spread… For instance, check out how this montage about Aziza working her ass off to earn a mountain of money gains momentum by moving from one type of layout to another:

Between such constantly evolving artwork, the plot curveballs, and the tonal shifts, I never knew what to expect when I turned a page. Hyper-dramatic pathos could be interrupted by a talking donkey, a sensitive portrayal of mundane squabbles could suddenly give way to a shocking outburst of violence… Bong Joon-ho would be proud!

That said, as long as I’m drawing comparisons to other works, there are two creators that come to mind. One of them is Craig Thompson, whose sumptuously detailed compositions and eye-popping surrealist imagery wouldn’t look out of place in Shubeik Lubeik – and not just because he also had a stab at this sort of Eastern fantasy in 2011’s Habibi (a much more uneven comic, but by all measures an astounding-looking one).

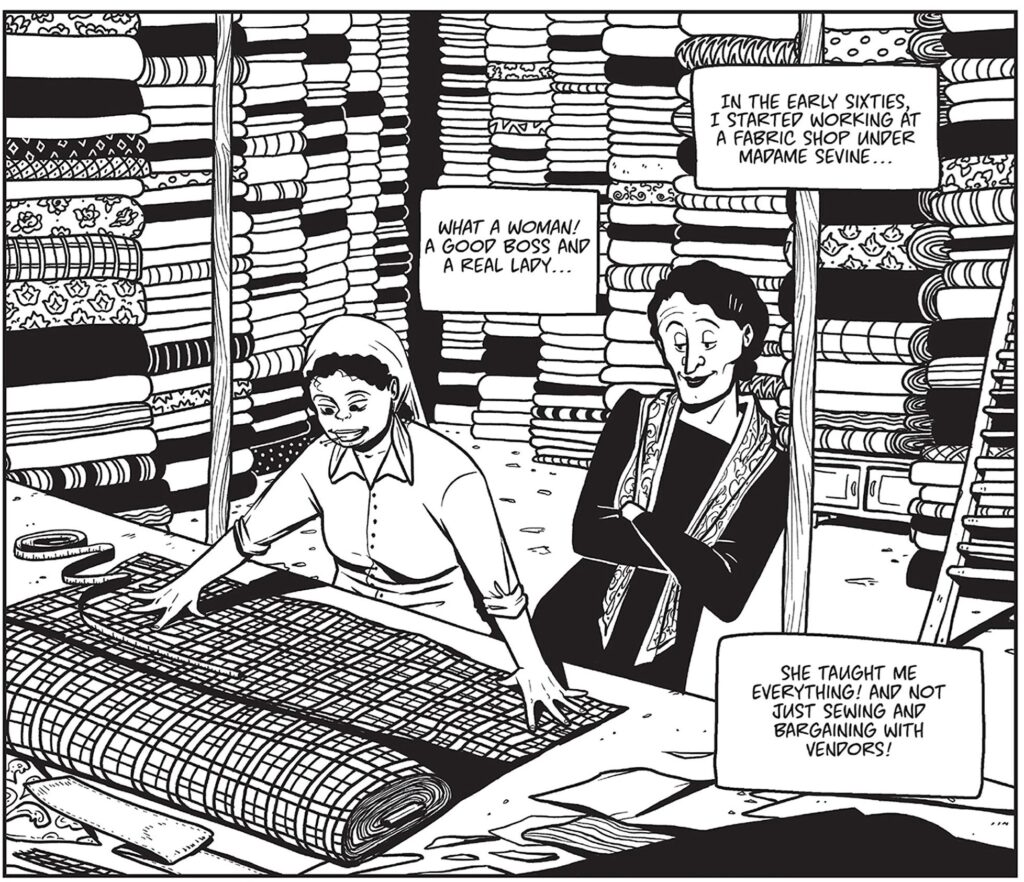

The other creator I kept thinking of was Will Eisner. Not necessarily The Spirit, but his later graphic novels, set in Dropsie Avenue, like A Life Force or A Contract with God and other tenement stories… Besides the – sometimes humorous, sometimes melodramatic – cruelty, there is the sheer, off-the-charts expressiveness of the artwork. In the image above, have a look not only at the detailed rendition of the fabrics, but also at how much of the two women’s personality is succinctly conveyed by their faces, posture, and clothing.

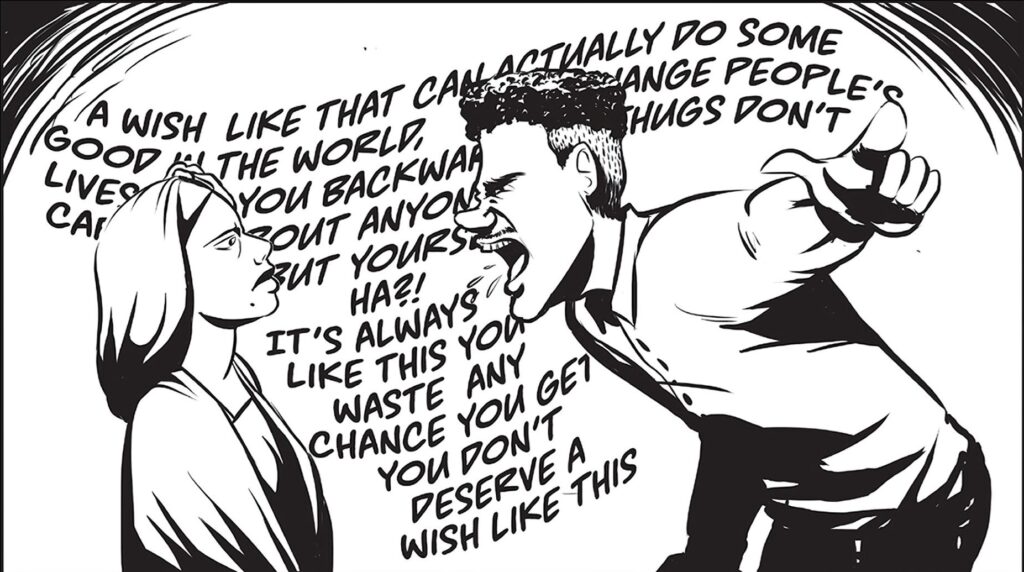

Similarly, in the in page below, you can find a very Eisneresque combination of squiggly panel borders and an extreme close-up to communicate a pungent state of mind:

As you can see, the effect is seriously enhanced by the placement, size, and shape of the lettering (again, much like Eisner used to do). Deena Mohamed’s translation pays close attention to this component of the comic, often drawing words in ways that, more than telling you what the characters are saying/hearing, compellingly contribute to the images’ mood and fluidity…

Moreover, like Habibi, Shubeik Lubeik borrows much of its sense of design from Arabic calligraphy. That alphabet appears to inform the curves of certain drawings and even the layout of several pacy, zig-zaggy pages.

Most notably, Deena Mohamed merges different types of scripts to illustrate the wishes (or, better yet, the djinns) themselves:

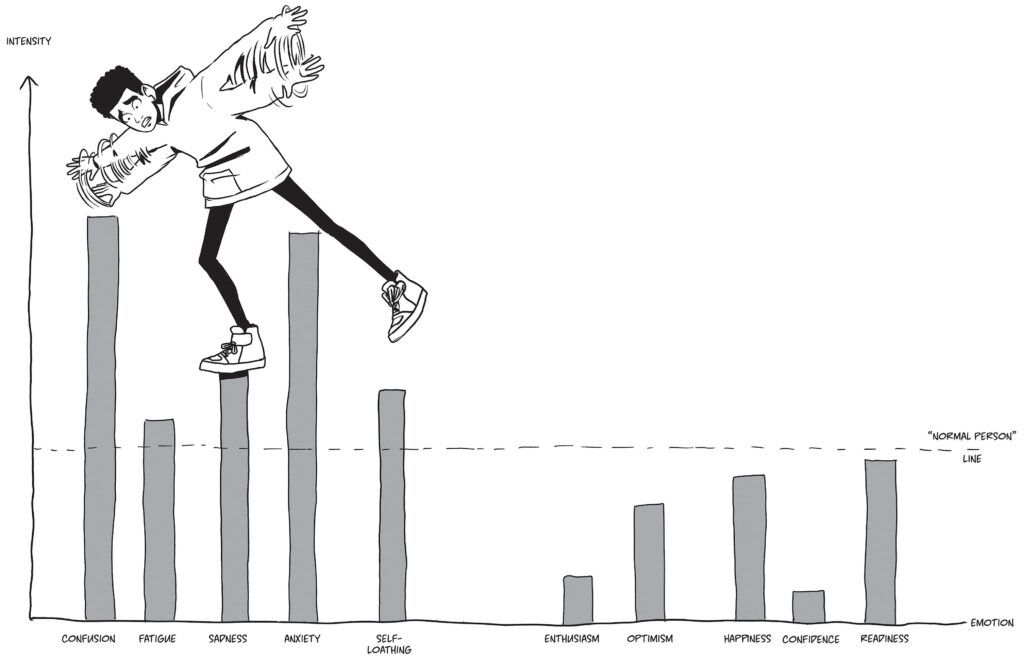

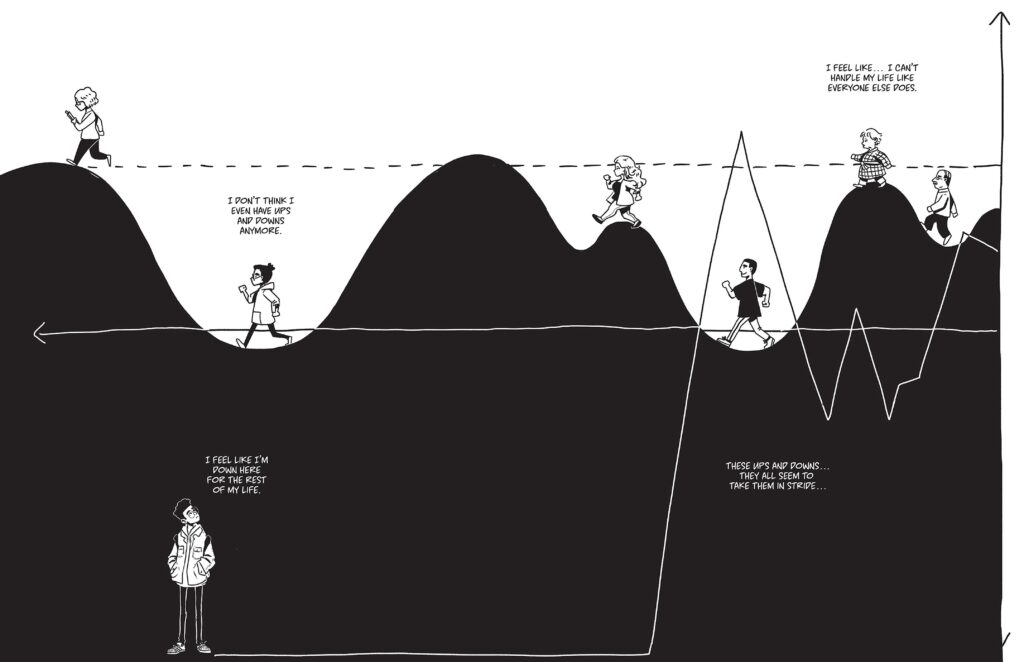

As I pointed out before, the second chapter is the most inventive in terms of comics language. If the first and third tales feature their share of big, bodacious sequences bursting with manic pencils, this section is tasked with capturing Nour’s low energy and all-consuming self-doubt, along with occasional peaks of anxiety. Mohamed does this by extensively showing us what goes on inside the protagonist’s head as well as the outside world, giving readers privileged access to Nour’s alienated perspective, the sense of isolation, and the feelings that no one else can grasp.

The challenge is to immerse us in a person’s depression in a way that still contains action and is not excessively dependent on words (after all, as much I praised the lettering, extensive blocks of text don’t always play to the medium’s strengths). Shubeik Lubeik pulls this off masterfully by acknowledging that, despite the lethargic body, Nour’s mind is actually quite restless, even if stuck in an insidious spiral. In an inspired decision, Mohamed uses a series of charts to both describe Nour’s psychological state and demonstrate the character’s self-reflexivity:

There is something in the air. Perhaps reflecting an ever-growing fixation on the price of unbridled power, consumption, and self-fulfillment, the last couple of years saw the publications of two other comics with a relatively similar premise. Paul Cornell’s and Steve Yeowell’s whimsical graphic novel Three Little Wishes is about a control-freak lawyer who gets three wishes from a fairy and obsesses about how best to use them. In turn, in Charles Soule’s and Ryan Browne’s nutty mini-series Eight Billion Genies, every person in the world suddenly gets a genie that grants them one wish each. In both cases, the result is pretty funny and more than a bit weird… and just as concerned with the ensuing practicalities and moral quandaries that could come from the massification of miracles, distinguishing between selfish and altruistic – as well as between impulsive and strategic – wishers. And while the former eventually ventures into rom-com territory and slight political satire, the latter’s scope – and artwork – becomes substantially more chaotic and large-scale (and way more informed by western pop culture than Shubeik Lubeik).

Although I’ve no qualms about recommending Three Little Wishes and Eight Billion Genies as highly enjoyable in their own right, at the end of the day I still have to go with Shubeik Lubeik for Gotham Calling’s book of the year. It’s a comic that I found constantly surprising and engaging – both visually and in terms of storytelling – and reading it made me go through a range of disparate emotions unparalleled in 2023.

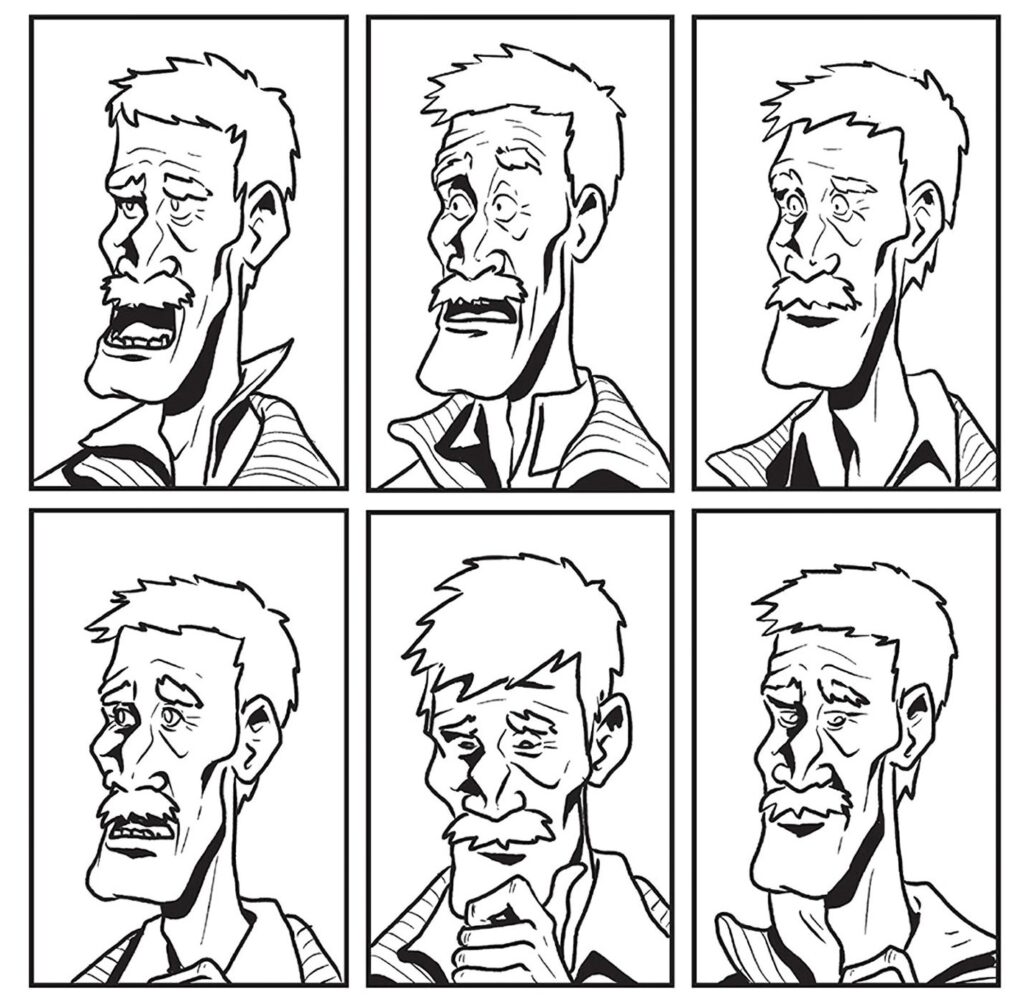

Here is a glimpse into what my face probably looked like as I moved from page to page: