The fact that the second volume of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters finally came out should’ve made the pick for Gotham Calling’s 2024 Book of the Year a clincher. Emil Ferris’ long-and-eagerly-awaited continuation of her dense, brilliant debut opus keeps up the impressive standard of dazzling visuals, sprawling narrative, and thematic breadth set by the first installment.

Once again, Emil Ferris resorts to the device of stream-of-consciousness ballpen drawings on a notebook paper of a grade-school fan of old horror movies and comics to compellingly engage – in quirky, brutal, and haunting ways – with topics ranging from classic art to gender norms, from the Nazi Holocaust to life among the underclasses of 1968 Chicago. There is an oddly timeless feel to the book, although I suppose it also taps into the current cultural moment, as some the most enthralling works of last year likewise used nostalgia-tinted horror imagery to translate existential anxieties with touching creativity (from David Small’s Eisneresque anthology The Werewolf at Dusk and other stories to Jane Schoenbrun’s beautifully eerie film I Saw the TV Glow). And while the shock of the previous volume’s inventiveness and originality isn’t there anymore, Ferris’ assured experimental storytelling and commitment to turn *every* *single* *page* into a mini-masterpiece make this a highly rewarding and affective read, as we get to delve deeper into the protagonist’s fucked up family life and into the investigation of her neighbor’s mysterious death. The two books of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters are instantly recognizable as fundamental contributions to the medium that I will no doubt revisit over time.

Still, if I’m to be honest, the most fascinating read of 2024 was actually a reprint…

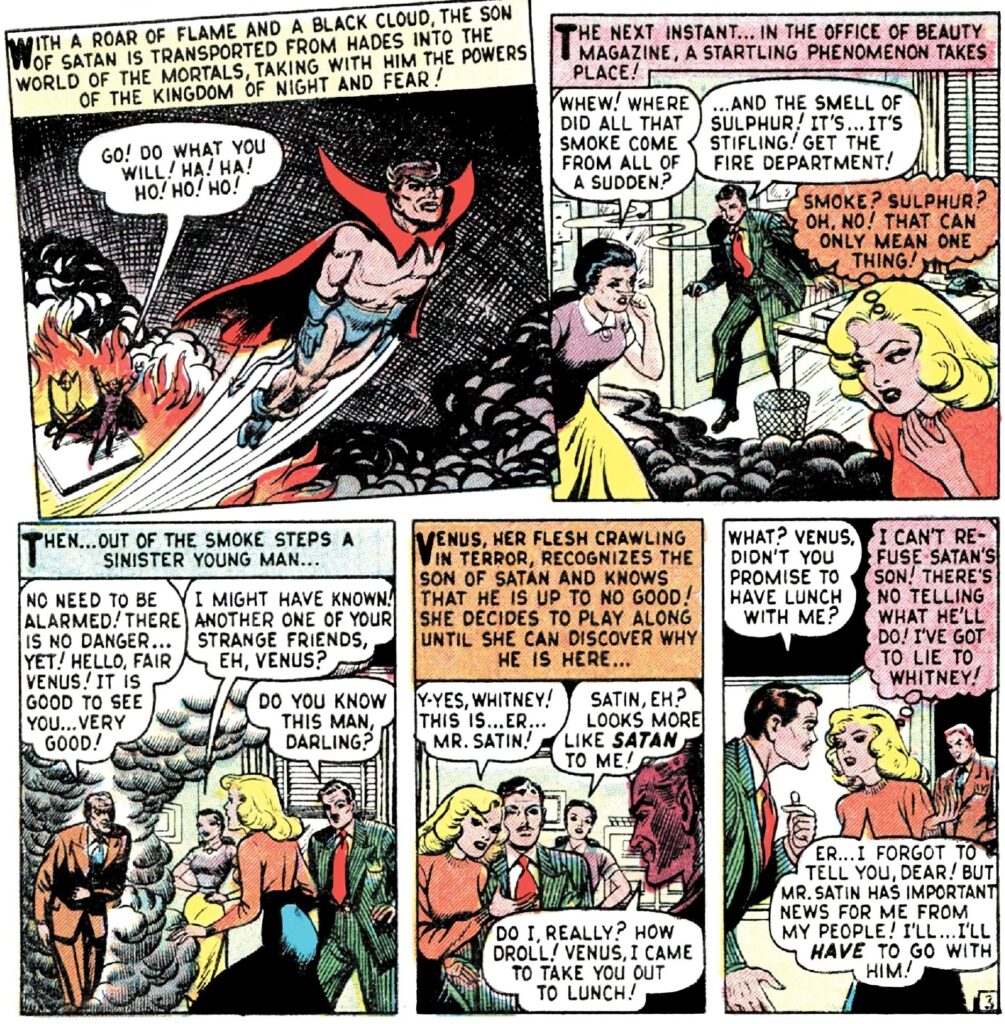

Back in 1948, (pre-Marvel) Timely Comics were throwing all kinds of shit at the wall to see what stuck, so somebody came up with the idea of doing a romcom series about Venus, the Goddess of Love, coming to Earth (initially from the planet Venus?!) and working for a beauty magazine, where she fell in love with her boss, Whitney Hammond. Things only got more bonkers from there, as, for the next few years, a host of writers and artists shifted the comic from genre to genre, turning it into an incredible time capsule of evolving trends during that wild postwar interlude when superheroes’ popularity had lost the initial momentum and publishers were eagerly searching for the medium’s next big thing.

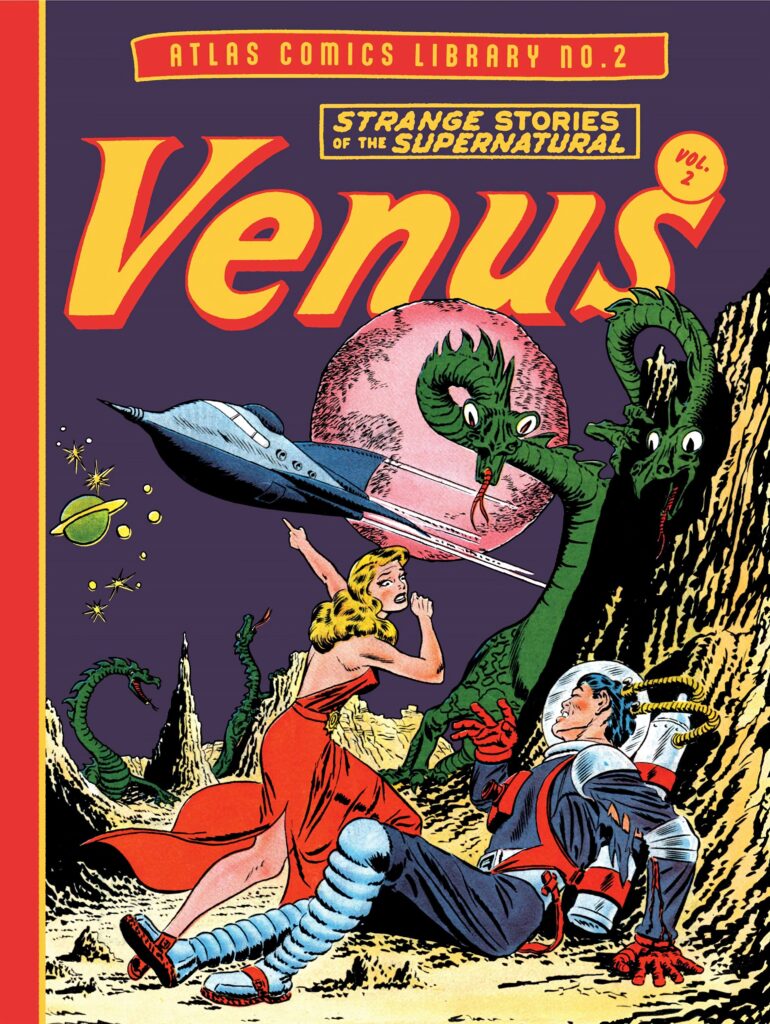

The series’ first nine issues had been collected in a volume over a decade ago, as part of Marvel’s Timely and Atlas Masterworks line, but for some reason those folks never got around to republishing the rest of the run, which was a shame because that’s where things got really strange and experimental. Fortunately, in the meantime, Fantagraphics has struck some kind of deal with Marvel, so I finally got to feast my eyes on this Golden Age gem in the form of a stunning-looking hardcover, edited by Michael J. Vassallo.

I never knew quite what to expect next while going through this book. Every time I thought I got it pegged, to some degree, it threw me off with an oddball story decision or a shockingly vicious line… If one tale is about a jealous secretary trying to trick Venus in order to try to get her job and marry Hammond, in the next one Venus is interviewing a scientist and so she gets on a rocket and flies to the moon (in 1950), where there is a volcano eruption and she has to bargain with Jupiter for help.

The stakes keep varying wildly, occasionally reaching the levels of a Superman comic, even if Venus’ solutions don’t usually rely on superhuman strength, but rather on her ability to manipulate people into falling in love. There isn’t exactly a formula, although the early stories do feature recurrent elements: Della the secretary scheming to discredit Venus in Hammond’s eyes, men doing stupid things (including destroying the world) because they get horny for our drop-dead gorgeous heroine, and Venus using her connections to the Roman pantheon (and sometimes the Norse pantheon, because why not) to get out of trouble.

And as if this wasn’t enough to make for a fun reading experience, the volume features lovely art by Werner Roth and, among others, a young Gene Colan. In fact, there’s an amazing roster of talented artists whose craft and professionalism elevate the material above mere campy shenanigans and into something that feels like an engagingly unique combination of enmeshed creative and commercial forces.

(Sounds like a kooky sitcom, right? Well, there’s mass murder in the next few pages…)

Atlas Comics Library no.2: Strange Stories of the Supernatural – Venus, vol.2 is clearly a labor of love and a treat for comic book fans, with thick paper, carefully restored colors, and wide enough margins for each page to be easily and fully visible in all its glory (as opposed to the annoying tendency in comics collections to fill the whole surface, thus obscuring some of the art or dialogue near the binding, where pages converge). If you’re reading this blog, you probably know I love old-timey covers, so it will come as no surprise how much of a kick I got from staring at these massive pages, with their neat mise-en-scène and taglines like ‘There was only one way to learn the horrible secret of the TOWER OF DEATH! You had to die, first!’

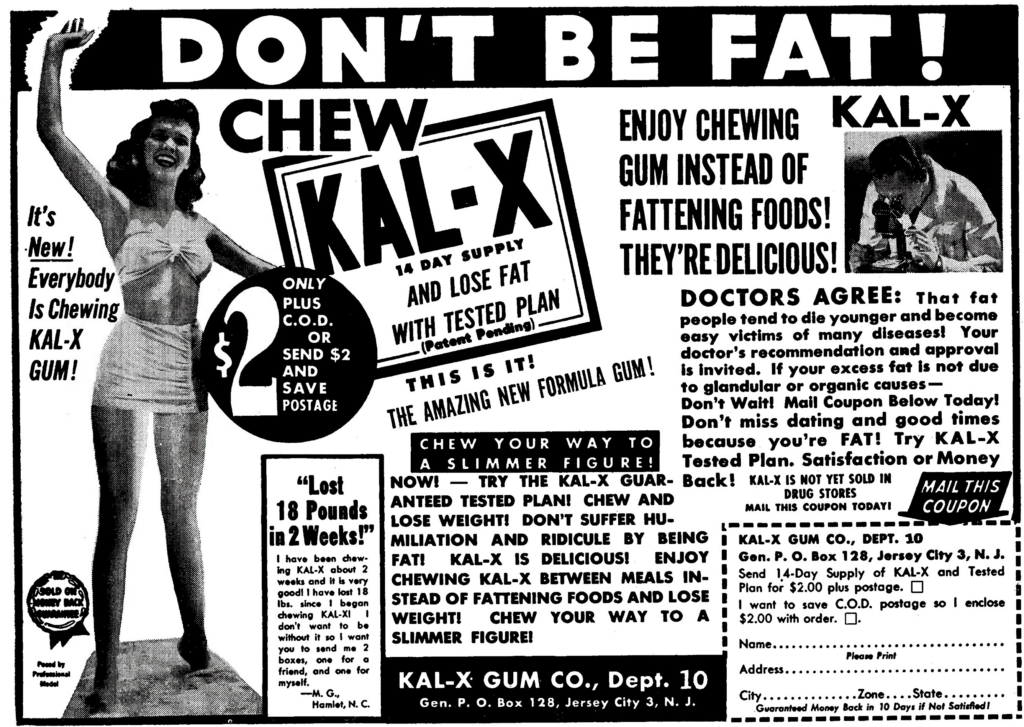

Plus, not only do we get a typically informative introduction by Vassallo, but also a reproduction of the original issues in their entirety, complete with the adverts. I’m sucker for this sort of stuff – the ads seem even more time-bound, telegraphing the era’s understanding of what was considered appealing for teenage girls, although not always in a linear way… Some of their values and assumptions aren’t so different from the ones in today’s publicity, but the thing is that they’re way more shameless and irony-free.

(And just wait until you see the ad for bras, a few issues later…)

Venus also contained unrelated filler material in the middle of each issue. Some of this were prose pieces of various genres, ranging from down-to-earth love stories (in ‘A Chance For Happiness,’ what I assume is a male writer has written a tale from the perspective of a woman in love with a male writer) all the way to supernatural thrillers (‘The Isle of No Return’ has got to be a Lovecraftian tribute/pastiche, hence its closing line), including a couple of paranoid tales typical of the zeitgeist (‘The Madmen of Mogan’ and the H.G. Wells’ rip-off ‘Death to the Hairy Monsters!’).

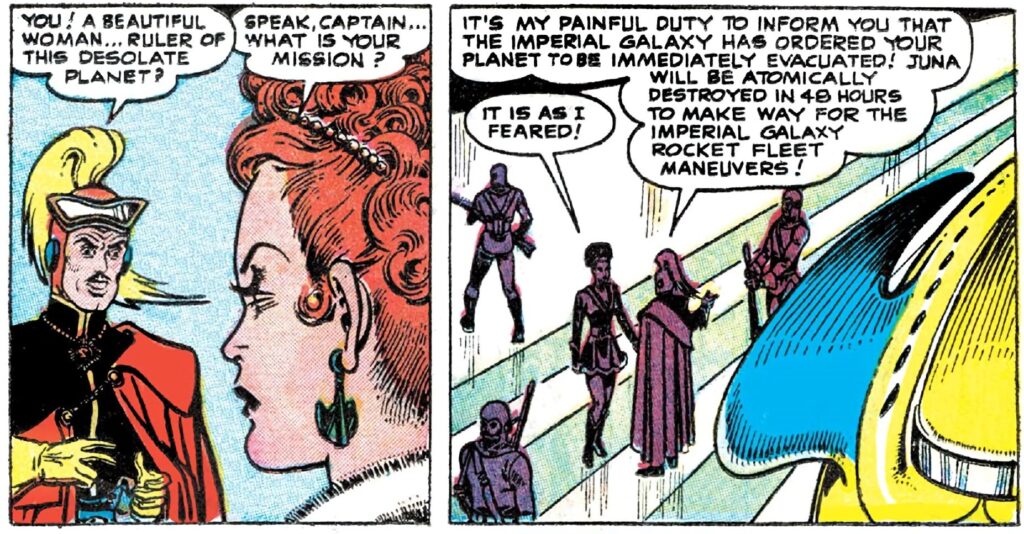

Other short stories are comics that share nothing with the Venus strip other than some superficial aesthetics, contributing to the general sense that editors were willing to keep trying out different stuff all the time. For instance, ‘The Madman’s Music’ is a chilling, quasi-poetic gothic yarn by Pete Morisi and ‘The Last Rocket!’ is a space opera that crams a mix of Star Wars and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy into just three pages… The latter is as frantic as it sounds, although Joe Maneely hilariously draws it in the most deadpan style:

To be fair, at least ‘The Last Rocket!’ has a weirdness-meets-romance-with-a-straight-face vibe that doesn’t feel entirely out of place. In fact, the series did take a hard turn to science fiction in the next issue. Tapping right into my passion for 1950s’ sci-fi, we get a tight little spy yarn within a robot rebellion, followed by a trippy adventure in which Venus is reduced to the size of an atom and becomes a prisoner in a scientist’ brain.

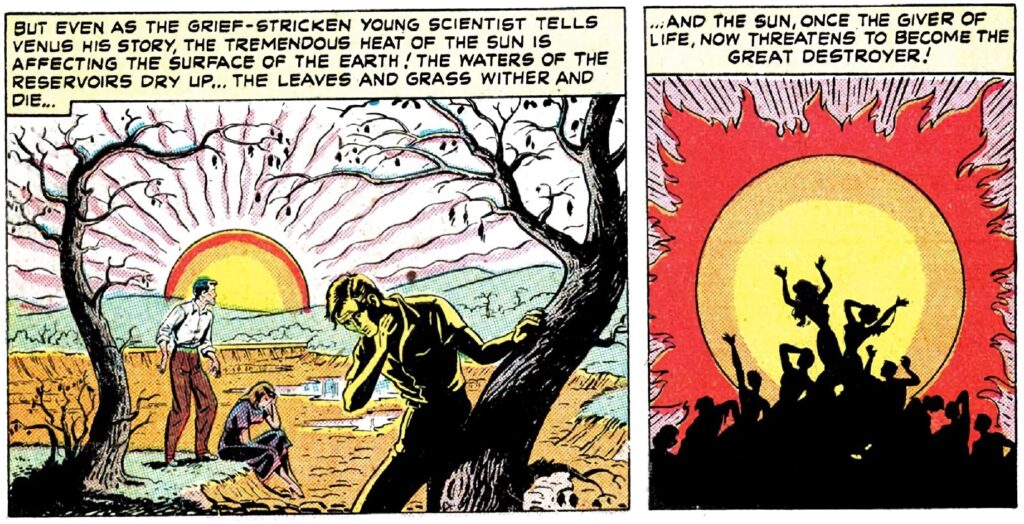

Hell, even before that, the issue opens with the end of the freaking world, showing us that the Earth has veered off its axis and is heading towards the sun, thus anticipating both The Twilight Zone’s ‘The Midnight Sun’ and The Day the Earth Caught Fire, including this terrifying atomic echo:

Now, the artwork notwithstanding, I’m not saying these comics hold up to being judged by conventional standards. Their plots are nonsensical (with incoherent behaviors, unclear motivations, baffling developments, loose ends) and, obviously, there is often an undercurrent of sexism at play in the way women are treated and depicted (as well as occasional racism, like in the ecumenical orientalist fantasy ‘Trapped in the Land of Terror’). However, if you’re willing to appreciate the comics as pop art surrealism, with a freewheeling, dreamlike flow of wacky ideas and memorable imagery, then Venus is an absolute hoot.

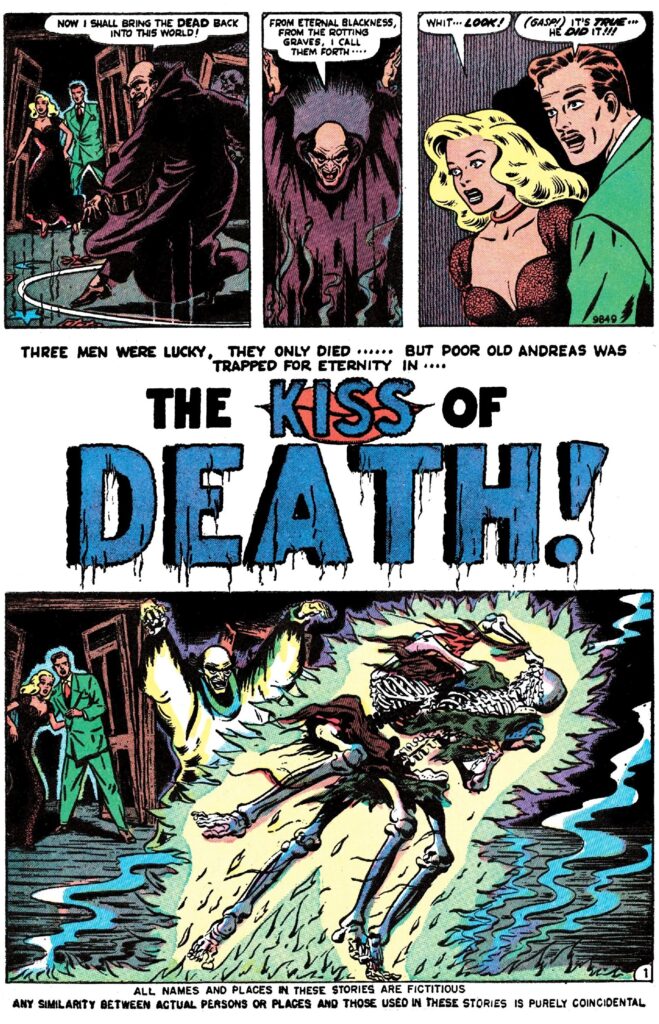

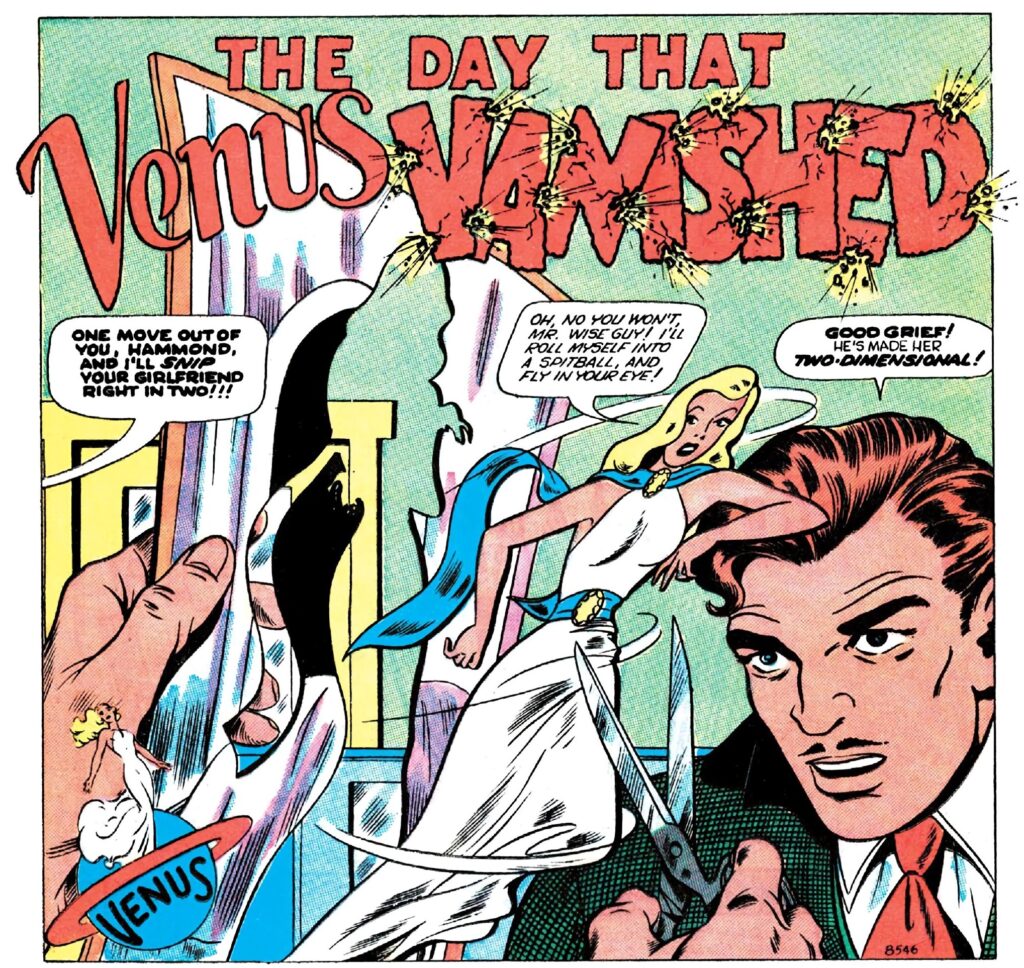

That said, it’s with issue #15 that the book takes a leap from cool to awesome. Bill Everett, who by then had assumed the writing, drawing, and lettering of all the Venus main features, turned the series into a pre-Lynchian horror book. If, at the time, EC was putting out tautly constructed short horror stories (which Fantagraphics has also been collecting in great books like Fall Guy for Murder and The High Cost of Dying), Everett delved into the sheer disturbing eeriness of unexplained setups, uncertain payoffs, and open-ended mysteries… The average tale would finish with Venus as befuddled and as creeped out as the readers, still unsure why dolls were bleeding in the previous panel and honestly concluding that ‘we’ll never know.’

Also, the lettering was much more creative:

Marvel fans will probably know Bill Everett as the creator of Namor the Sub-Mariner (to which he returned decades later, even penning a crossover that brought back Venus from obscurity, in 1973) or, more likely, as the co-creator of Daredevil. His stint on Venus, though, is the kind of run you get in comics every so often when someone comes along and memorably redefines a property through their bold personal vision.

Everett was not afraid to mess with whatever loose formula had been in place. In fact, through his inconsistent characterization, I’d argue he made the series much more progressive in terms of gender politics. Della stopped being defined as a jealous secretary and Venus herself, instead of asking gods for help all the time, became more active and even got some zingers (‘Death is cold, sir… but I assure you I’m very warm now!’).

Rather than fawning over Whitney Hammond, Venus assumed the primary role of paranormal investigator, halfway between John Constantine and Hildy Johnson, from His Girl Friday. She was now a committed reporter who defiantly chased after each hard-hitting story (for a beauty magazine) and no longer took shit from the condescending men around her.

Horror and romance can actually work quite well together. In comics alone, there are plenty of magnificent examples, whether it’s obscure short stories like The Vault of Horror’s ‘Reunion’ or avowed classics like Swamp Thing’s ‘Rite of Spring.’

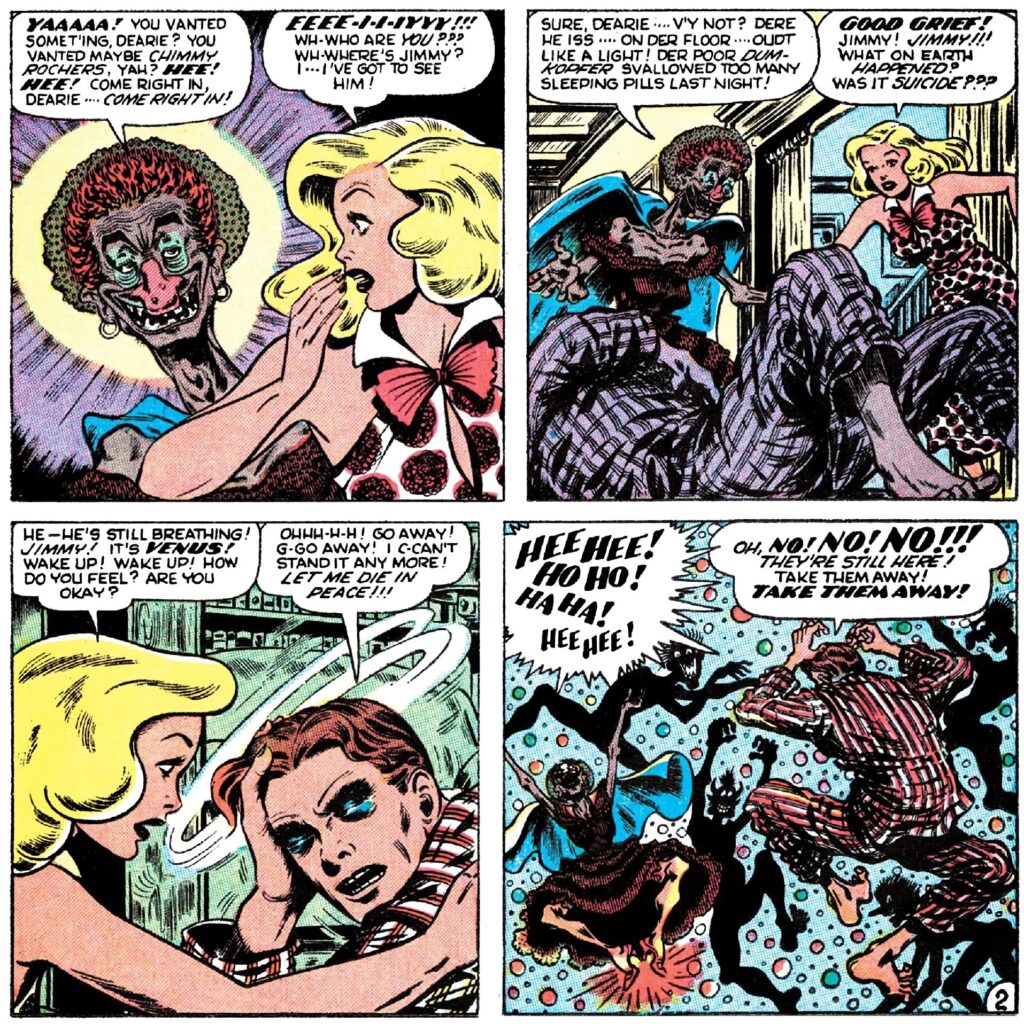

However, Bill Everett soon straight-up dropped Venus’ romance angle, except for a jarring bit in the Cold War monster epic ‘The Stone Man!’ (and, I suppose, the unforgettable final panels of the mind-boggling ‘The Kiss of Death!’). For the most part, Everett just dived into full-fledged horror, filling the issues with atmospheric artwork, macabre grotesqueries, and an increasingly dark tone. Perhaps he needed to get it out of his system, as expressed in the metafictional – and possibly autobiographical – tale ‘Cartoonist’s Calamity!,’ about a comic book author who is literally haunted by the freaky creatures he draws:

(I would be amiss if I didn’t point out Venus is wearing a pretty sweet outfit.)

Venus would go on to be retconned into the main Marvel Universe, most notably through Jeff Parker’s and Leonard Kirk’s enjoyable Agents of Atlas, in 2006, but these pages suggest a whole different type of alternate history. If pre-Code Hollywood was batshit insane, the same can be said for many of the books made right before the comics industry accepted the CCA’s censorship, in 1954. For a few years, publishers were no longer targeting just kids, yet they weren’t sure what exactly they were doing instead, so they let creators experiment with all kinds of crazy shit. And this volume is a wonderfully entertaining reminder of how comics could’ve soon evolved in offbeat and much more imaginative ways if only they had been let loose for longer…

Hell, these read like just the sort of comics that would appeal to Karen Reyes, the protagonist of My Favorite Thing is Monsters!