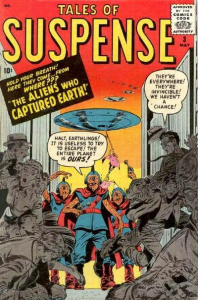

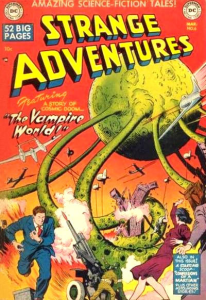

A couple of months ago, I recommended (re)visiting H.G. Well’s The War of the Worlds. This classic sci-fi horror novel became a massive influence on pop culture as the urtext for books, films, television shows, theatre plays, and video games about alien invasions, Martian and otherwise – whether it was William Cameron Menzies’ campy Invaders from Mars or Tim Burton’s nihilistic Mars Attacks! (although not Harry Horner’s hysterically propagandistic Red Planet Mars, which took the idea of alien contact into a whole other direction…). Naturally, the story had quite an impact on comics as well, where this subgenre found a fertile breeding ground, especially during the paranoid 1950s (presumably because it channeled Cold War anxieties):

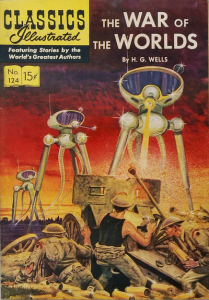

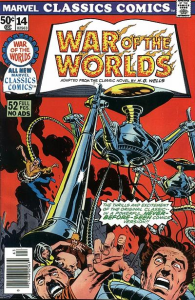

Besides spawning countless imitations and variations, The War of the Wolds has been the object of explicit – if more or less loose – adaptations as well, from Orson Welles’ notorious 1938 radio play to last year’s Fox TV series (which I haven’t seen). On the big screen, there was the cornball 1953 version produced by George Pal (set in California, with an unmistakable Red Scare subtext and a religious slant to the final twist) and Steven Spielberg’s War on Terror-era disaster movie (which moved the action to New York and, in the process, shifted the parable’s target from British to American hubris).

As for comic books, besides having a field day playing with the fiction-taken-for-reality panic surrounding Welles’ radio broadcast (which inspired Weird Science’s ‘Panic,’ Secret Origins’ ‘The Crimson Avenger,’ and The Spirit’s ‘U.F.O.’), the medium has also delivered its fair share of takes on H.G. Wells’ work…

With this in mind, I want to discuss a bunch of cool comic book projects that took things one step further by actually building expansive universes on The War of the Worlds’ scaffolds.

Let’s start with the saga that ran in Amazing Adventures #18-39 (1973-1976), set in a dystopic 2018 and following the exploits of the Spartacus-like Killraven, who leads a resistance movement in the aftermath of a second, more successful Martian invasion… Created by Roy Thomas and Neal Adams – and initially scripted by Gerry Conway – the series was a full-on action-packed Marvel adventure comic, one that often felt like some sort of LSD trip (like much of the company’s output at the time) yet it was also an explicit sequel to an 1898 novel.

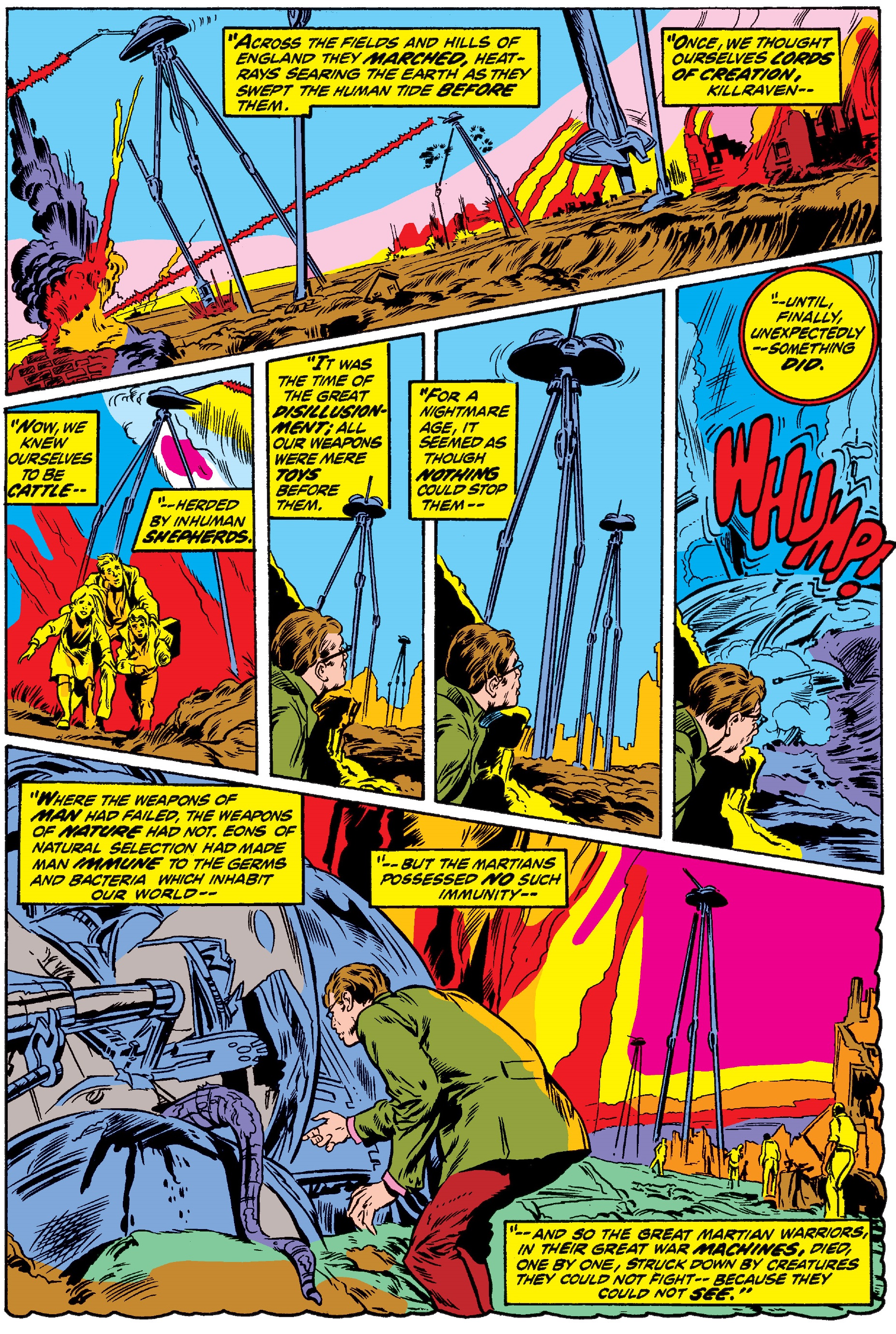

This counter-intuitive hybrid took no prisoners: the first issue, illustrated by Adams and Howard Chaykin (two artists with a quasi-naturalistic style reminiscent of old pulps), opened in media res with Killraven mercilessly slaughtering hordes of henchmen and mutants before the comic eventually took a break to sum up H.G. Wells’ book in an effective two-page flashback…

Amazing Adventures (v2) #18

Amazing Adventures (v2) #18

We soon learned that, one hundred years after the failed invasion of 1901 (unlike the comics discussed next week, which place the invasion in the year of the novel’s publication, this one respects the fact that Wells’ narrative was set ‘early in the twentieth century’), the Martians, now prepared with bacteriological immunity, finally managed to conquer Earth and subjugate the human race. Raised to be a gladiator by human collaborationists – the so-called ‘keepers’ – working for the Martian overlords, the brash, revenge-thirsty Killraven then rebelled and went on a revolutionary quest throughout occupied America that mostly took the form of psychotronic science fiction worthy of the proud tradition of imaginative futuristic war comics.

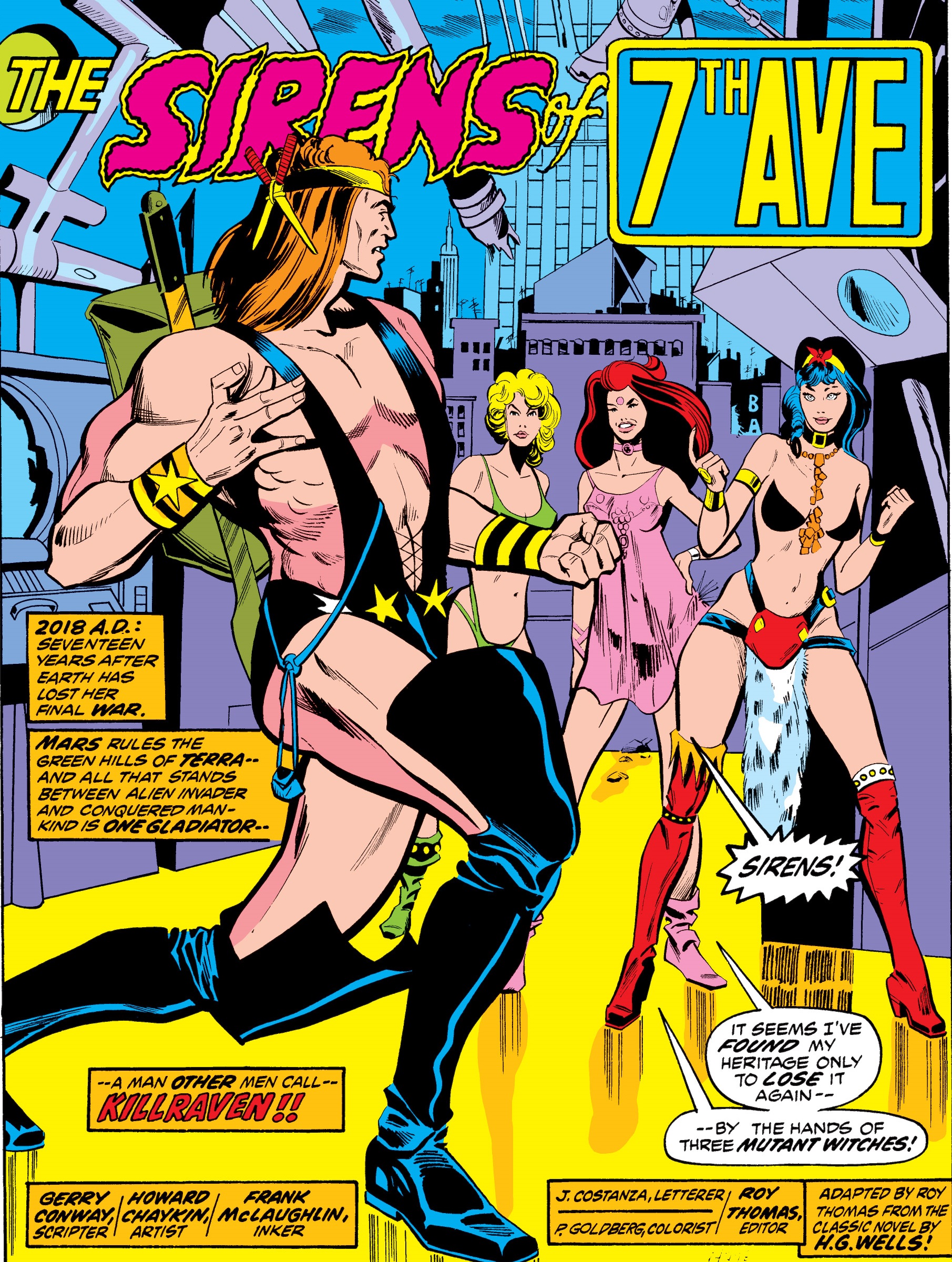

With its blatant counterculture influence and wild horror/fantasy imagery, this strange series is like a spiritual relative of Steve Gerber’s run on The Man-Thing at the time, as Killraven – who is plagued by telepathic daydreams – finds himself riding a purple serpent-horse and battling giant, disgusting monsters, cartoonish tyrants, and a trio of semi-naked women designed to attract men to their doom:

Amazing Adventures (v2) #19

Amazing Adventures (v2) #19

(Not to deny the obvious sexism behind this trope, but, to be fair, the sirens’ looks are no more preposterous than Killraven’s own attire… In fact, the overall kinky fashion sense seems to anticipate George Miller’s own post-apocalyptic vision in the Mad Max movies, years later.)

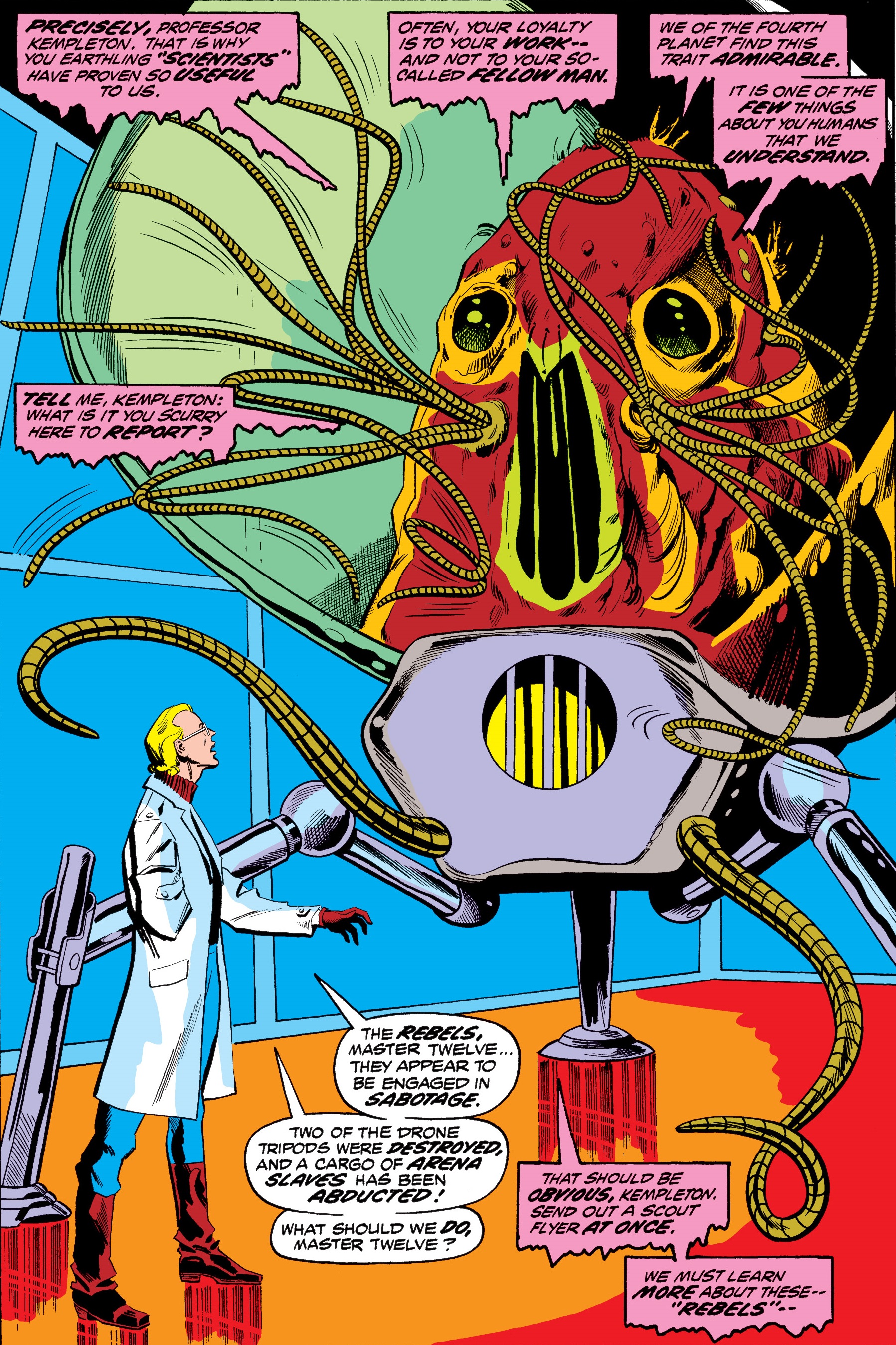

And in case you’re wondering if Howard Chaykin’s design of the Martians lives up to H.G. Wells’ description, I’ll let you to compare the two:

“They were, I now saw, the most unearthly creatures it is possible to conceive. They were huge round bodies—or, rather, heads—about four feet in diameter, each body having in front of it a face. This face had no nostrils—indeed, the Martians do not seem to have had any sense of smell, but it had a pair of very large dark-coloured eyes, and just beneath this a kind of fleshy beak. In the back of this head or body—I scarcely know how to speak of it—was the single tight tympanic surface, since known to be anatomically an ear, though it must have been almost useless in our dense air. In a group round the mouth were sixteen slender, almost whiplike tentacles, arranged in two bunches of eight each.”

Amazing Adventures (v2) #19

Amazing Adventures (v2) #19

Outside of the initial premise and the occasional sighting of Tripods, this comic may appear to have little to do with H.G. Wells’ book (starting with the fact that we are expected to root for humanity’s violent triumph over the aliens, as if having learned nothing from Wells’ deconstruction of anthropocentrism). Yet, like the original, this too is an allegorical and critical take on the values of its time. Between the Cold War, Civil Rights struggles, and rising environmentalist concerns, the early 1970s led to some of the weirdest visions of the future… In film, we got A Clockwork Orange, Soylent Green, Westworld, The Omega Man, Silent Running, and Sleeper. In comics, we got DC’s Kamandi, The Last Boy on Earth and, yes, Marvel’s War of the Worlds, which channeled the era’s misanthropy by viciously denouncing humans’ callous willingness to turn on each other in the name of selfish interests (as you can see in the dialogue above).

Between the campy visuals and the clunky writing, I admit the series did start off as pretty much an awful mess, even if I retain a soft spot for its devil-may-care energy. Things became gradually more interesting once Don McGregor became the main writer (with #21), not least because of his flair for political irony. In the issue ‘Washington Nightmare’ (which opens with this cheeky description of Killraven: ‘…a man who has sworn to win back humanity’s right… to destroy itself!’), a band of futuristic pirates host a slave auction at the Lincoln Memorial. In the next issue, Killraven’s torture in the White House has echoes of George Orwell’s 1984. And in the *next one* the rebels come across the Watergate tapes while putting together a New Year’s Eve party:

Amazing Adventures (v2) #24

Amazing Adventures (v2) #24

Moments like this one, in addition to the narration’s tendency to comment on the action by directly referencing contrasts with the present (of the ‘70s), meant that the comic often relativized our worldview, framing readers’ consumerist urges and current concerns as ultimately transient and petty from an outsider’s vantage point – an act of estrangement comparable to H.G. Wells’ own gesture of defiance against humanity’s self-importance in The War of the Worlds. Other slices of satire took place in ‘Something Worth Dying For!,’ where a proto-knight protected his ancestor’s legacy (which turned out to be a set of cereal boxes), and ‘Only the Computer Shows Me Any Respect!,’ where a computerized simulation of The Hound of the Baskersvilles became simultaneously an indictment of alienation and a metaphor for the plight of Native Americans. (A fill-in issue by Bill Mantlo then tackled the Black Power movement.) More generally, the psychedelic aesthetics (including experimental layouts and lettering) combined with the fact that the series revolved around a gang of rebellious misfits – the self-labeled Freemen – with different genders, colors, and (dis)abilities fighting against tyranny in an American wasteland lent the comic a markedly iconoclastic vibe.

Indeed, besides keeping – and sometimes amping up – the offbeat humor, the sexual tension, and the surreal tone, Don McGregor also introduced remarkable supporting players, including Carmilla Frost (a molecular biologist who gave mainstream comics’ first interracial kiss), Sabre (a disgruntled African-American slaver), and Volcana Ash (a flirty bombshell with pyrokinetic powers). Meanwhile, his Killraven was a cross between an idealist hero and the kind of cunning barbarian that could’ve starred in Savage Tales.

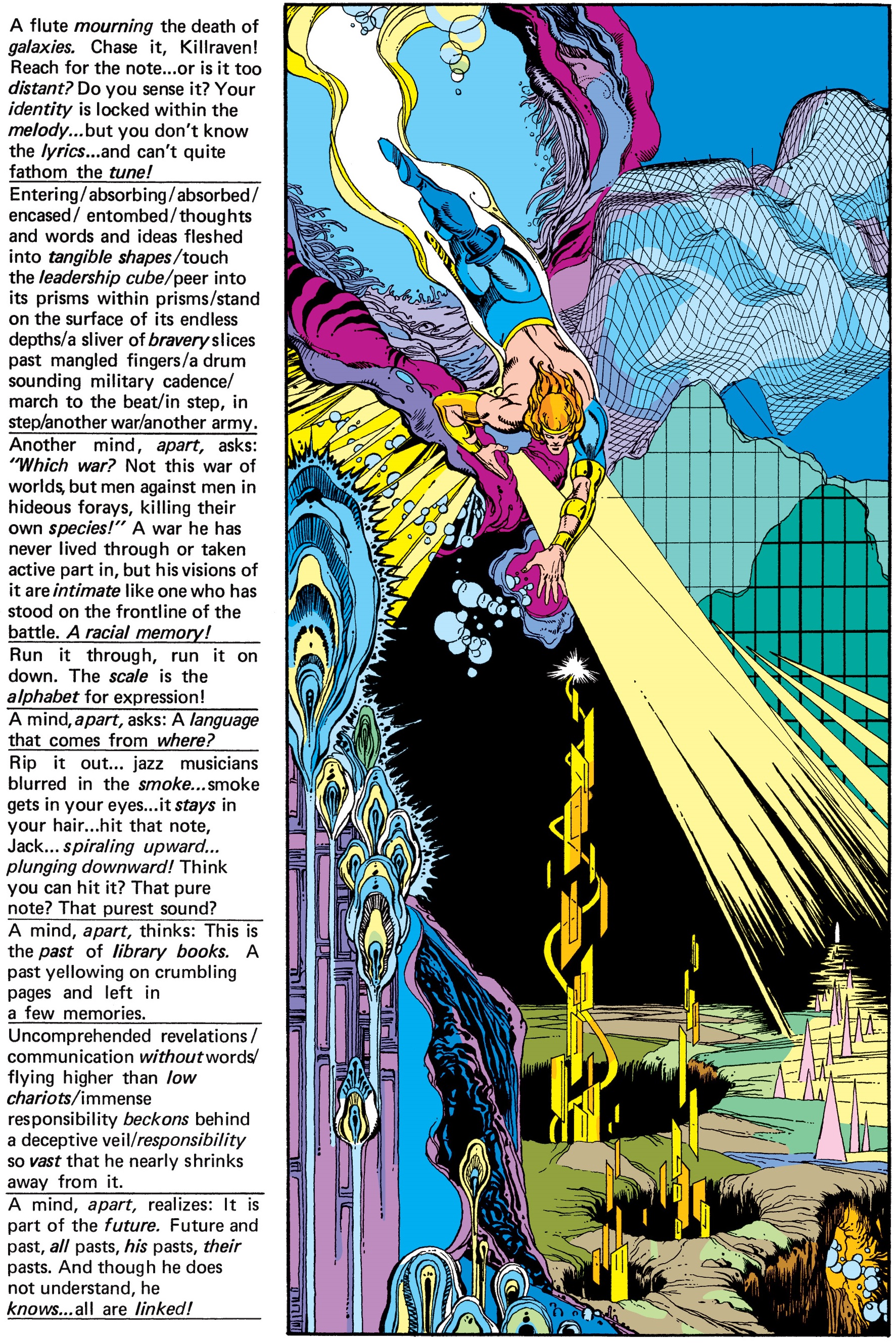

McGregor’s run was further elevated when P. Craig Russell came aboard as regular artist, starting with #27. Russell’s more lyrical style merged particularly well with McGregor’s portentous – if verbose – voice… Firing on all cylinders, not only did they have the characters encounter misunderstood remnants of the 1970s (perhaps never more impressively than in ‘The Day the Monuments Shattered,’ a high point of the series), but they also had them come across technology supposedly developed in the 1990s (i.e. in the diegetic past, yet in the creators’ imaginary future). For instance, in what is arguably the series’ most bizarre tale (with the possible exception of the baffling ‘The 24-Hour Man’), Killraven and the Freemen visit a futuristic Nashville musical arena:

Amazing Adventures (v2) #32

Amazing Adventures (v2) #32

(Curiously, although the comic has fun speculating about the intervening decades between its period and the 2001 invasion, the various creators seem comfortable with the implication that everything until the ‘70s was pretty much familiar, as if the first Martian attack had had little historical impact…)

I’m also a fan of ‘Red Dust Legacy,’ in which we learn about Martian reproduction. Basically, Martians are genderless and not only do they reproduce asexually (‘…they always did strike me as being kinda dull!’), but they do so without great emotion – their infants grow like fruits on a branch and the severing of parent and child is nothing more than that to them (‘The tree does not celebrate! The tree does not mourn!’). What I like about this issue is that, after treating the aliens as feared others and inscrutable outsiders for so long, we finally get a closer perspective on their mindset and even a degree of empathy, especially as we learn that the younger, Earth-born generations may be less willing to annihilate humans (a nod to the Vietnam-era generation gap?). In turn, Killraven, with his determination to massacre a bunch of younglings, comes across as particularly vicious. The ending then piles up one ironic twist on top of another. (Between this story and ‘Mourning Prey,’ you could really see the series evolving into more ethically ambitious territory in the final issues before its cancellation…)

It’s a cult-worthy run. By issue #29, the comic had come such a long way and gained such a distinct identity that the covers of Amazing Adventures even dropped the ‘War of the Worlds’ logo, temporarily rebranding the main feature as ‘Killraven, Warrior of the Worlds’ (even though the series had actually become more of an ensemble piece, with numerous subplots and an increasingly diverse cast). Seven years after Amazing Adventures’ cancellation, Don McGregor and P. Craig Russell tied up some loose ends in the 1983 graphic novel Killraven: Warrior of the Worlds, although the actual war would only wrap up in 2010’s Marvel Zombies 5 – of all places! – where Killraven teamed up with Machine Man and Howard the Duck. (Like most Fred Van Lente comics, Marvel Zombies 5 is both hilarious and quite clever at reworking disparate cultural references, paying tribute to the original novel as well as to the pulpy 1970s’ saga while having a blast with the notion that Killraven is a violent fanatic…)

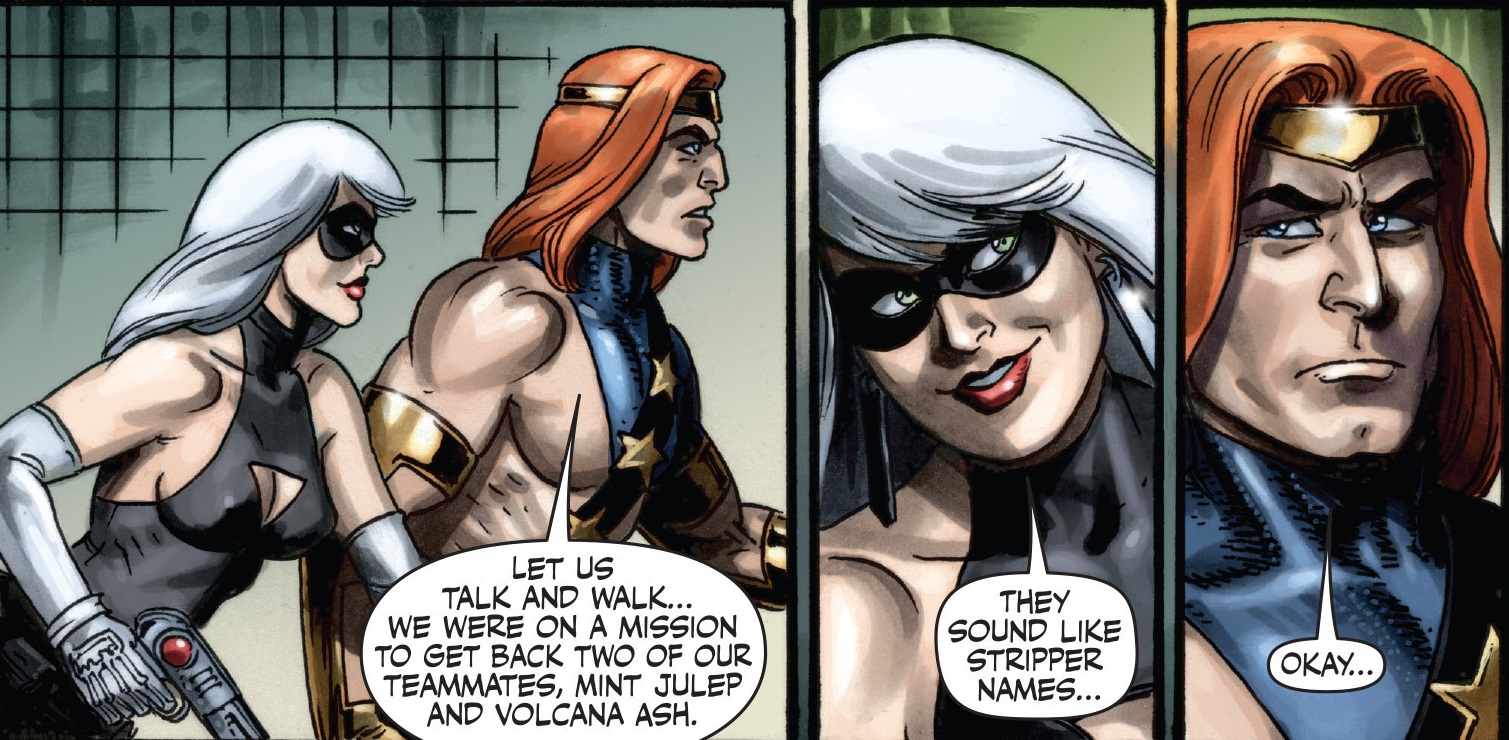

In the meantime, we also got a reboot in the form of a 2003 Killraven mini-series by Alan Davis – a streamlined retelling of the Freemen’s early adventures, with plenty of tweaks. More reader-friendly yet less fascinatingly idiosyncratic, this lively, two-fisted yarn is not only miles apart from the novel (even if it recovers Wells’ red weed and poisonous smoke), but it also loses some of the earlier comic’s most interesting choices, especially when it comes to the female characters (for instance, the green-skinned Mint Julep used to be much more unabashedly feminist). The main attraction here is the art, with Alan Davis once again proving he can turn the most outrageous designs into stylish eye candy. Indeed, the whole thing feels like a vehicle for Davis – with smooth inks and colors by Mark Farmer and Greg Wright – to pit gorgeous, athletic bodies against elaborate mutations:

Killraven #3

Killraven #3

These various odd takes on The War of the Worlds came to occupy a recognizable place in Marvel lore. Notably, Bill Mantlo strengthened the connection to the Marvel Universe already back in 1976, having written Marvel Team-Up #45 (set before Amazing Adventures #37), in which Spider-Man met the Freemen after time-travelling to their 2019, and Amazing Adventures #38, in which Killraven visited the remnants of the Miami Museum of Cultural Development, coming across holographic projections of Iron Man and Doctor Strange, among others.

More recently, Wolverine and Black Cat visited a version of this future in 2011’s raunchy screwball mini-series Claws II, written by Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray, who managed to push the material’s sexual undertones even further…

Wolverine & The Black Cat: Claws II #2

Wolverine & The Black Cat: Claws II #2

The Marvel franchise – a major vortex of today’s pop culture – is thus tied to a work of Victorian literature! I get quite a kick out of this sort of mix of high and lowbrow (like when Young Indiana Jones Chronicles had an episode built around both Franz Kafka’s writings and the Pink Panther movies).

Sure, purists will point out that Killraven’s saga isn’t set in the core continuity of Earth-616, but rather on Earth-691 (the same from the Guardians of the Galaxy comics). Still, H.G. Wells’ Martians have also occasionally appeared in Marvel’s main universe. For instance, Paul Cornell wrote them into his awesome 2007 mini-series Wisdom, where these aliens (gloriously redesigned by Manuel Garcia) attempted an interdimensional invasion of the United Kingdom. The Martians’ appearance fit particularly well into that comic’s exploration of British mythology, a point driven home by Pete Wisdom’s internal monologue: ‘They’re the British past. Here to do to us what we did to the world.’ (James Robinson later followed this up with the amusing All-New Invaders #12.)

And just to stress the return of Wells’ concepts to British soil, I’ll wrap things up for today with this Monty Python reference: