This is the time of the year when bloggers share their best-of-the-year lists. I don’t usually play along because I mostly read old stuff and don’t have enough of a grip on current publications to make any authoritative claim about the state of the field. Still, this time around I thought I’d jump into the conversation.

In the world of comic books, I guess Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina is this year’s critical darling – i.e. the middlebrow, non-superhero graphic novel I offer to people who don’t typically read comics in order to justify my love for this kind of stuff (even if the kind of stuff I read isn’t always like this). Don’t get me wrong: it’s not just the fact that Sabrina made it to the Booker Prize’s longlist… This is a damn fine comic, one that exploits the medium’s language and ability to slow down the pace, capturing the melancholia of everyday gestures. While Sabrina isn’t exactly groundbreaking, Drnaso manages to mobilize his artistic and tonal influences (Chris Ware, Rutu Modan) in order to tell a story that cleverly (and touchingly) taps into the zeitgeist through its empathy with characters stuck between depressingly familiar violence and the underworld of conspiracy theories. I particularly like the fact that we are never shown the inciting incident, so it’s up to us to decide who deserves our trust and compassion, making it less a tale of ‘reality vs fake news’ and more a work about what each of us chooses to believe in.

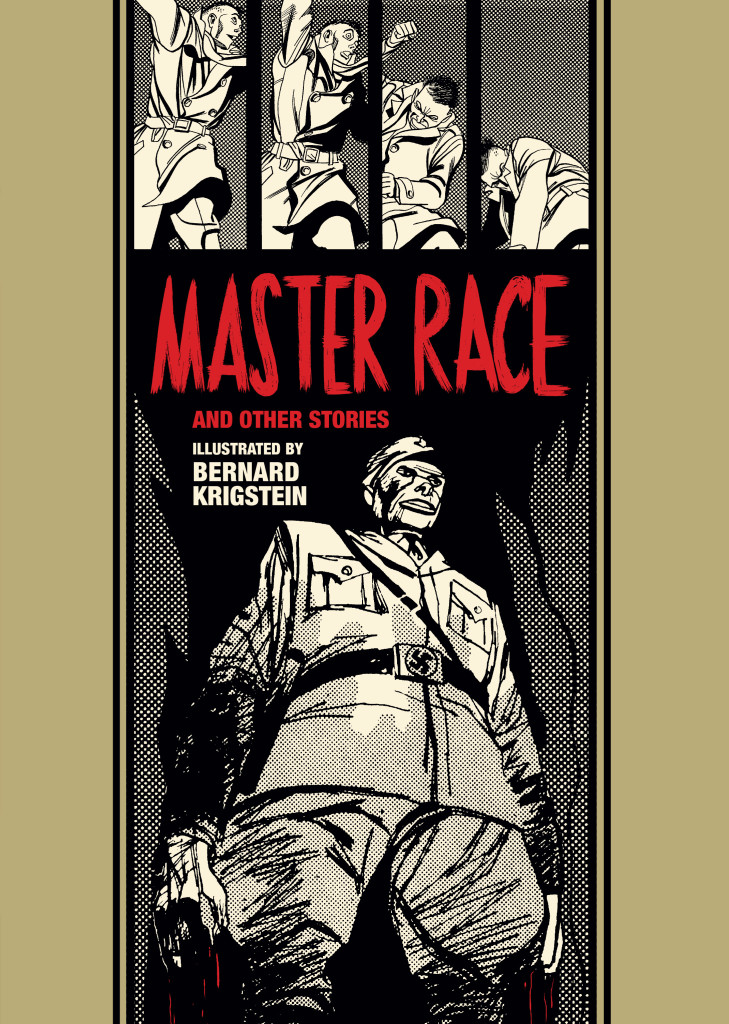

That said, if I was to pick one book that came out this year and that exemplifies the potential of comics, I wouldn’t go with Sabrina. I would go with Master Race and other stories.

(That’s right, I chose a reprint collection and, shockingly, it’s not Batman: The Brave and the Bold – The Bronze Age Omnibus, volume 2!)

Master Race is one of the latest instalments in Fantagraphics’ set of luscious volumes collecting short stories from 1950s’ EC Comics. Each volume is organized around a specific artist, featuring all (or a large chunk) of his contributions to series like Weird Science-Fantasy and Tales from the Crypt. The comics are reprinted in glorious black & white, thus highlighting the draftsmanship, and they’re accompanied by essays on the artists and their work. The vast majority of stories were plotted by Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein (and scripted by Feldstein), but EC had such a notable assortment of eccentric artists that each book has quite a distinct feel.

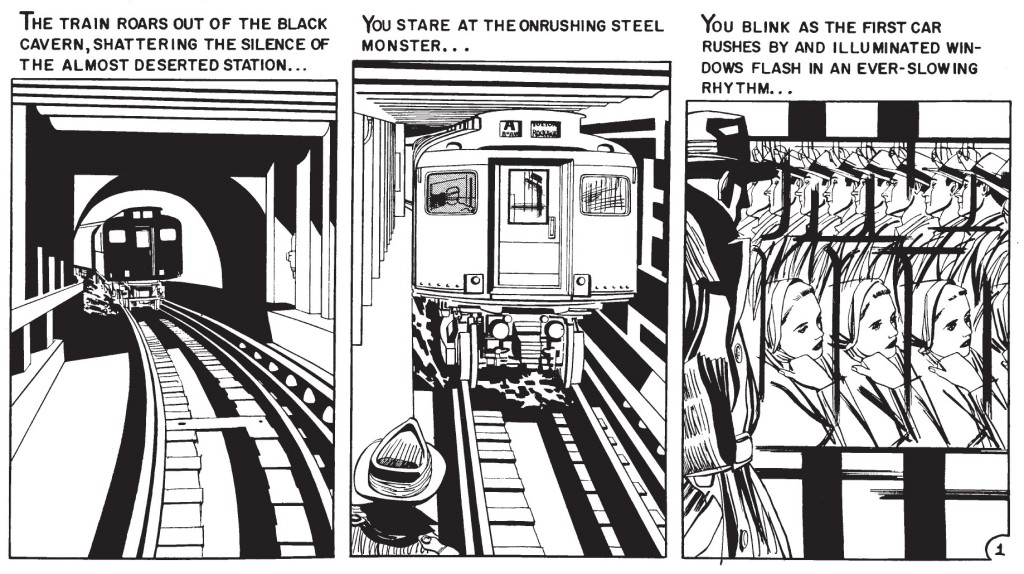

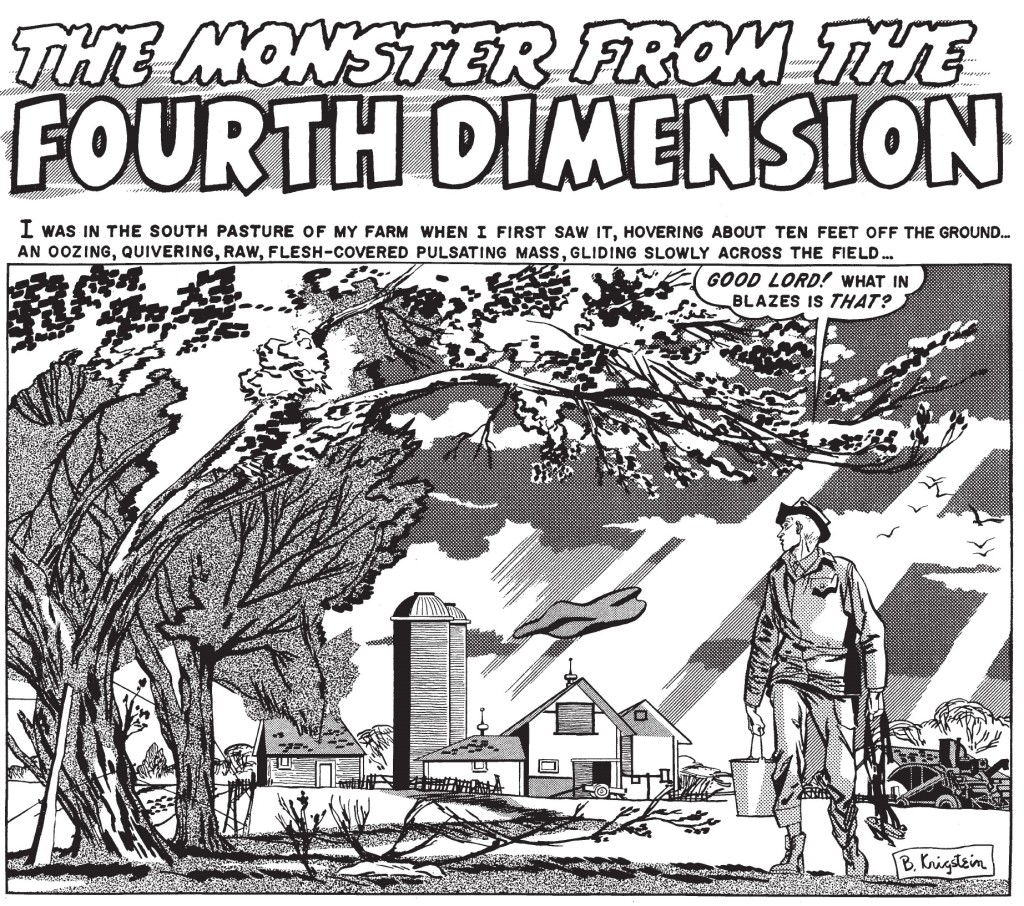

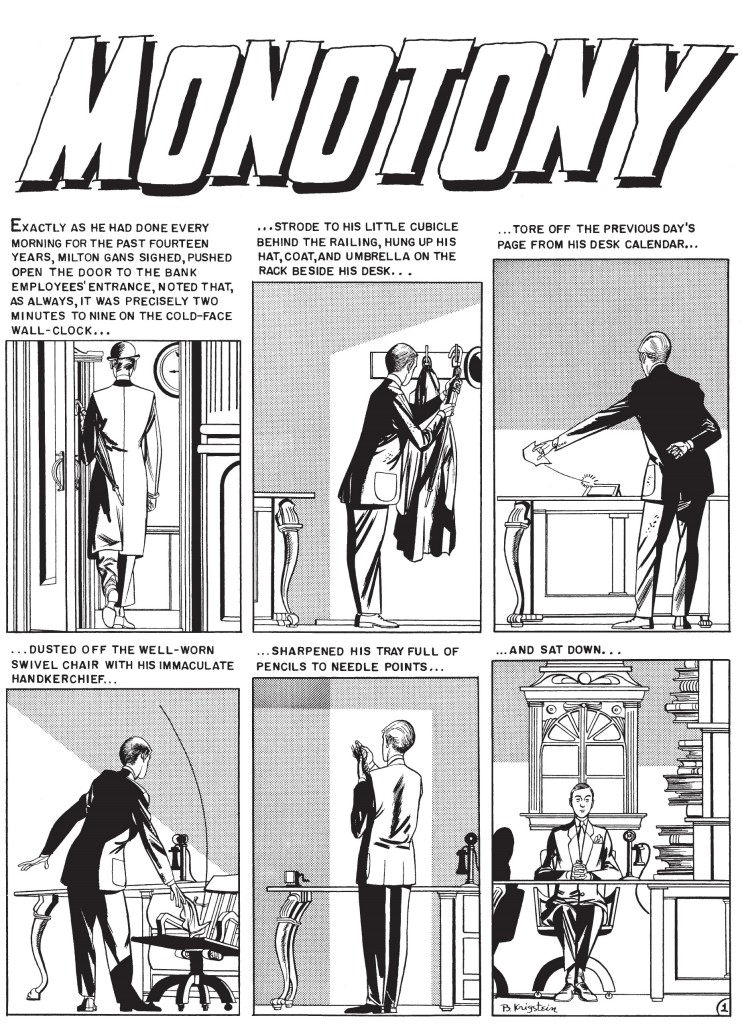

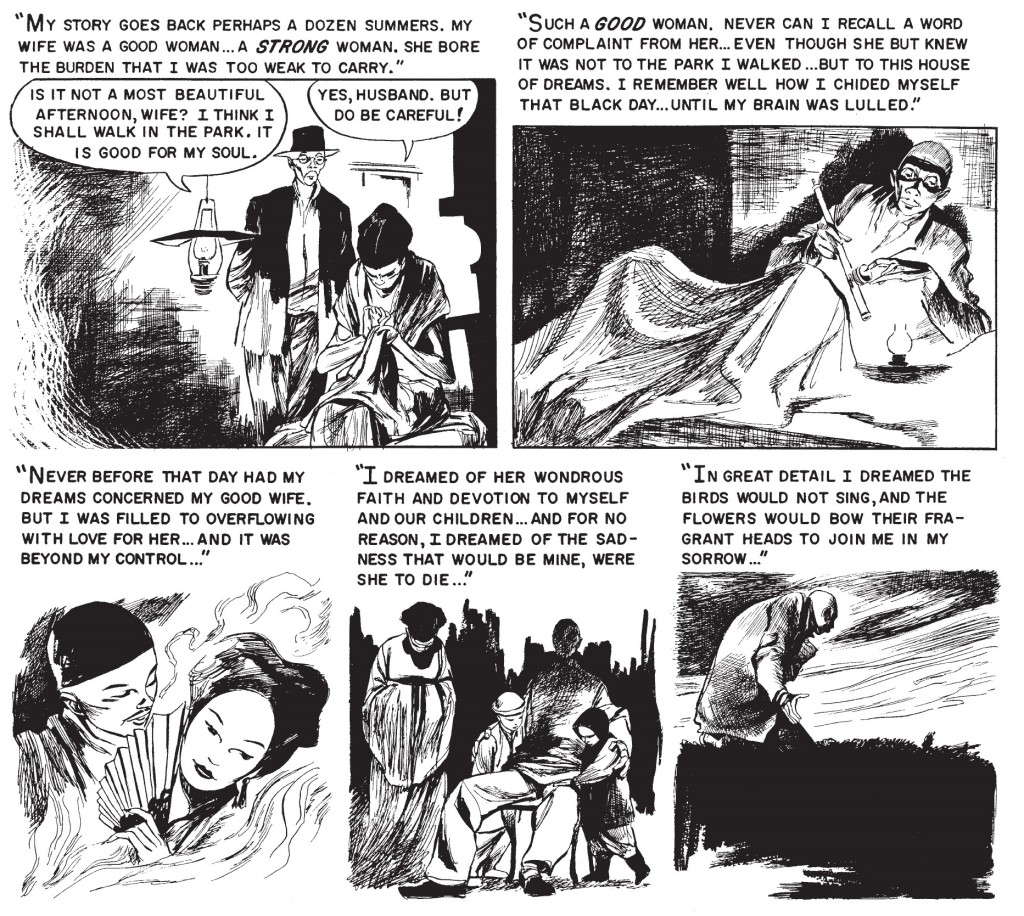

This volume collects 32 stories drawn by Bernie Krigstein between 1953 and 1956. Krigstein was a classically trained artist who treated comics as part of a tradition stretching back to the earliest cave drawings and ancient Chinese scrolls, creating monthly masterpieces within the confines of six-page long stories in ten-cent comic books. Sixty years later, his experimentations with the breakdown of time and visualization of movement remain a sight to behold:

It’s such an excellent and varied anthology. While many Fantagraphics collections revolve around a specific genre (The High Cost of Dying is mostly horror, 50 Girls 50 is mostly sci-fi, etc), Master Race isn’t confined to one type of narrative. Instead, it engages with the possibilities of different traditions of storytelling: we get some mind-bending science fiction, genuinely macabre horror, hard-hitting crime yarns, twisted comedy, magical realism, political parables, and riveting aerial combat, not to mention old-school human drama.

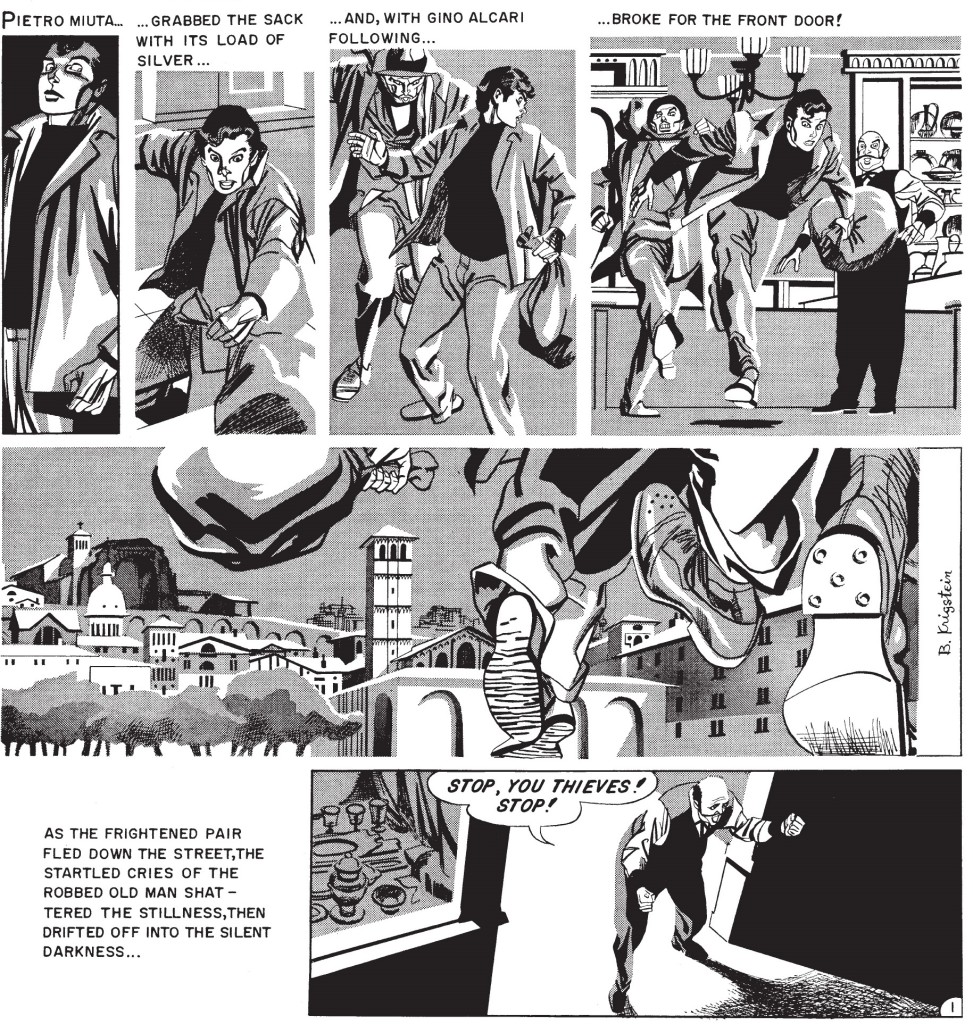

The cast ranges from daring astronauts to bored bank clerks, our focus shifting from a deluded scientist to a frustrated housewife, from a superstitious WWI pilot to an embittered boxing champ, from a despotic plantation owner in the Mato Grosso jungle to a couple of thieves in Italy…

Al Feldstein’s purple prose may be too much for some readers, but I just eat it up with a spoon. This is how he describes a space ship landing: ‘The ship plunged, tail first, toward the surface of the alien sphere… Then, like an angry monster, the ship spit flame and sparks and blue smoke at the planet rushing up toward it… The spitting roaring metal dragon slowed in its downward tail-first fall, as if the planet were suddenly afraid and had hesitated in its eager advance upward… The ship was down, bumping gently to rest amid clouds of rocket exhaust, standing proudly like a warrior stands over his vanquished foe…’ These captions may not tell us anything Krigstein’s art couldn’t convey by itself, but they help create one hell of a mood!

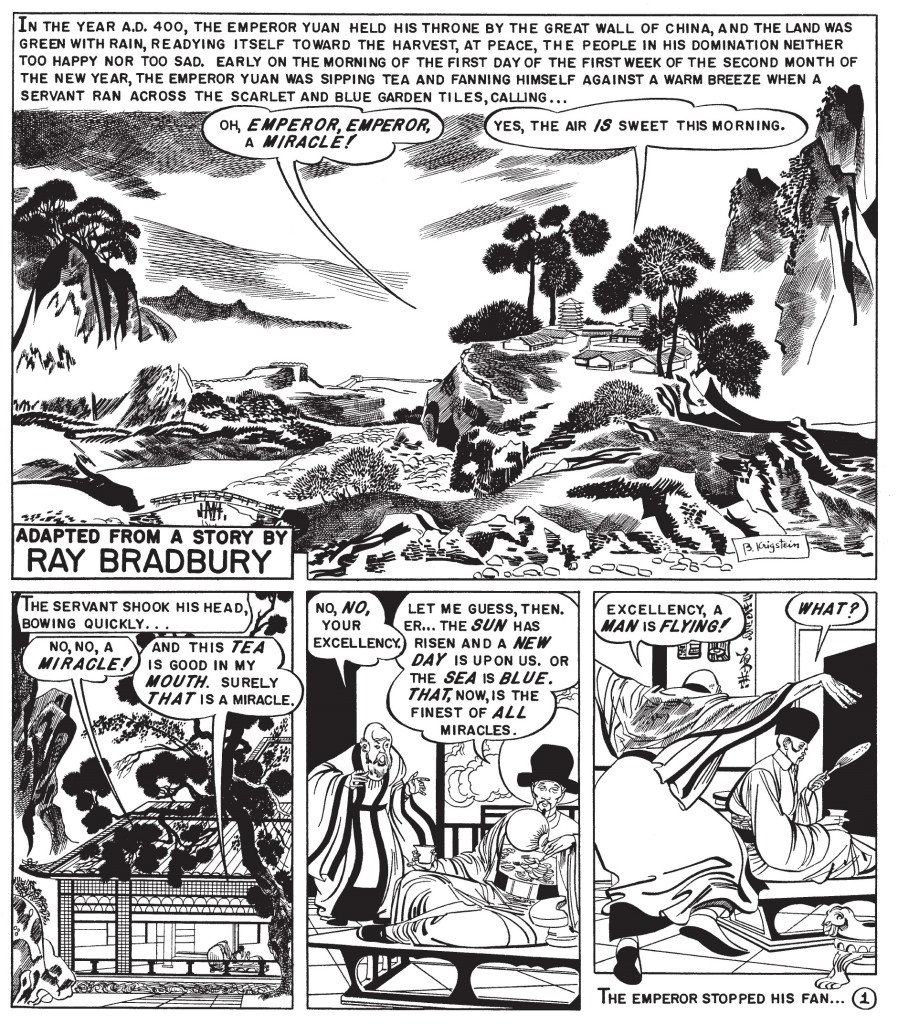

Feldstein isn’t the only talented writer around. Notably, the collection includes an adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s beautiful story ‘The Flying Machine,’ which means we get a handful of neat Bradbury-esque dialogue exchanges:

Sure, there are missteps, but not that many… Even ‘Fulfillment,’ one of a couple of stories to use the cringeworthy misogynist stereotype of the nagging wife, slightly redeems itself with an amusing punchline (which, at least from today’s vantage point, feels like a parody of the transcendent importance of tourism for postcolonial countries).

At the core of Master Race, though, is Bernie Krigstein’s art. The book contains a long introduction, titled ‘Master of Design,’ in which Greg Sadowski analyses each of the tales collected in this volume, and it finishes with three essays about Krigstein (by S.C. Ringgenberg), the restauration process of the story ‘Slave Ship’ (by J. Michael Catron), and the rise and fall of EC Comics (by Ted White).

Sadowski’s piece is particularly informative, pointing out stylistic choices and motifs (like how Krigstein tended to use drawings of hands in effective ways), providing behind-the-scenes context, and explaining technical aspects, for example regarding Krigstein’s approach to the 3-D story ‘The Monster from the Fourth Dimension.’

There is a kind of arc in the book. According to Sadowski, Bernie Krigstein went from an artist who sought to push the medium’s boundaries to one who realized the existing conventions of cartooning were already worthy of respect (even if he ended up moving on and, after 1957, concentrated mostly on fine art and cover illustrations).

Along the way, we get to see Krigstein elegantly play with a range of different styles and techniques to suit each particular assignment. His pencils can be soft, light, and romantic and then, a few pages later, they suddenly deliver gut-wrenching levels of violence (especially in the cruel ‘The Pit!’). I love how the opening of ‘Monotony’ smoothly sets the titular tone:

There are so many gems like this one… ‘More Blessed to Give’ is built like a series of symmetrical, film noir-like panels that tell the parallel stories of two spouses plotting to kill each other (a Cold War metaphor?). ‘Pipe-Dream’ is suitably drawn as if, like its protagonist, we are seeing everything shrouded in an opium haze:

As a history geek, I’m also fascinated with the way these comics reflect and react to the times around them. For example, besides telling a gorgeous space adventure, the opener, ‘Derelict Ship,’ is a story about explaining to the next generation the sacrifices made in the recent fight against fascism. The shadow of World War II also looms large over the brilliant tale that gives the collection its name – living up to its reputation as a hallmark of the medium, ‘Master Race’ shows us the unforgettable encounter between two men haunted by memories of Nazi Germany. Everything is designed to punch you in the gut, from Krigstein’s noirish cinematic angles to the accelerating rhythm of the train (a classic symbol of the Holocaust), with Feldstein’s second-person narration and the eerie closing line suggesting the impossibility of fully understanding what took place and how people were able to do what they did.

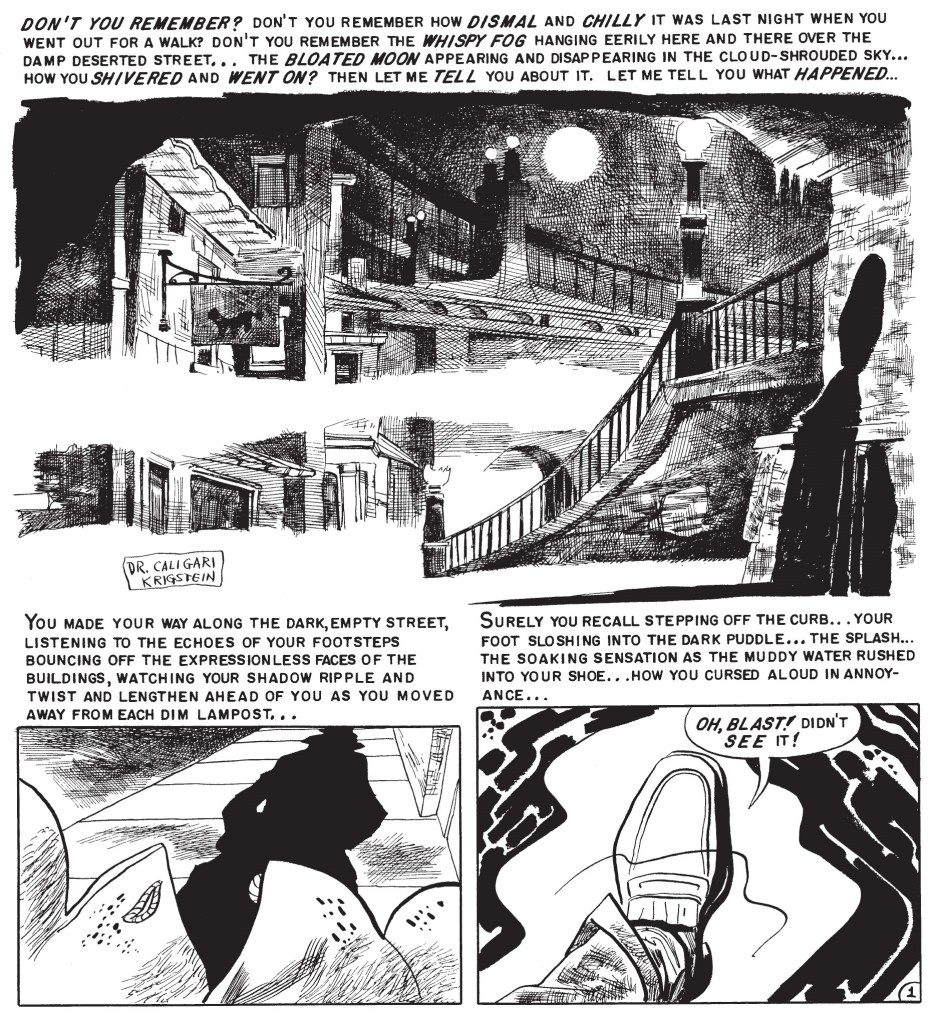

There are other political entries, from the slavery-themed ‘Slave Ship’ (which came out at a time when segregation was still law and civil rights up for debate) to the ambiguous colonial tale ‘Mau Mau’ (about the uprising against British rule in Kenia). It’s also hard not to discern Cold War anxieties hidden under fantasy trappings… ‘The Flying Machine’ is all about how science can be seen both as exciting progress and as an existential threat (a theme revisited in the pitch-black comedy ‘The Pioneer’), thus channeling key debates of the Atomic Age. The Otto Binder-written ‘You, Murderer’ feels like a jab at McCarthyism, since it features a grotesque hypnotist who makes someone kill an innocent man by convincing the protagonist that the victim is a communist spy – a device that’s made all the more powerful because the story is framed from the reader’s point of view, as if reminding the people holding the comic that they too were being subjected to a comparable type of manipulation.

(And if you have any doubts that Bernie Krigstein drew inspiration for ‘You, Murderer’ from the classic 1920 expressionist movie The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which also features an evil hypnotist, then look no further than the way he signed the story…)

Do yourself a favor and get your hands on Master Race. Just make sure you don’t pick up the wrong copy!