If you read the last post, you know I’ve been looking at Batman comics about drugs. Today I want to briefly discuss two stories from the early 1990s that approached this topic in extreme ways.

In his many adventures, the Dark Knight has taken quite a few drug-induced trips…

Batman #516

Batman #516

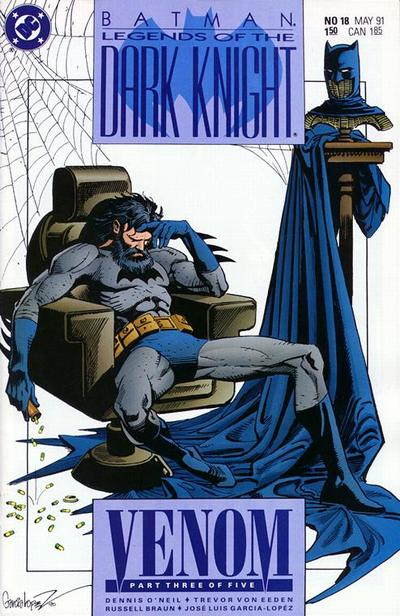

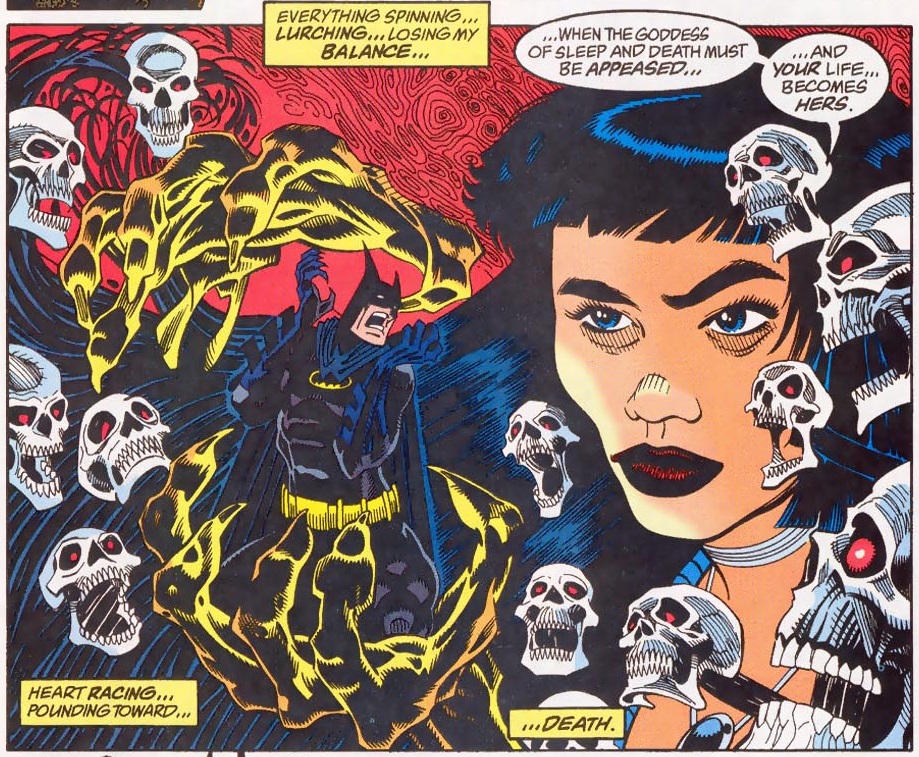

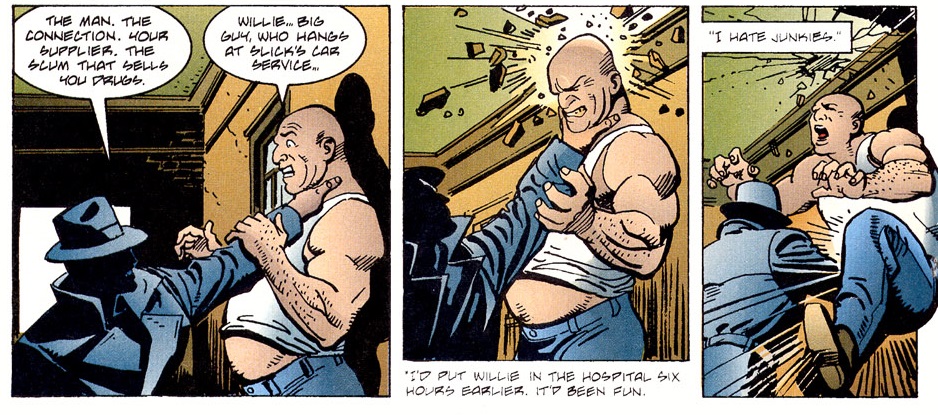

In 1991, however, Denny O’Neil took the extra step of writing a five-part story devoted to Batman’s consumption of – and subsequent addiction to – a designer drug. In ‘Venom’ (Legends of the Dark Knight #16-20), set in the early stages of Batman’s crime-fighting career, the Caped Crusader has a crisis of confidence after failing to rescue a little girl because he wasn’t strong enough to move some rocks. He therefore starts taking special steroids that not only make him stronger, but also turn him into a jerk who sadistically bullies those he thinks are weaker than him while laughing hysterically.

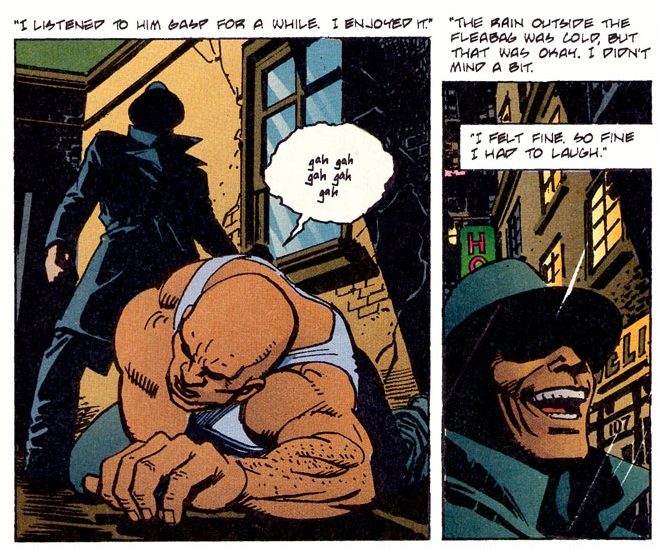

Notably, he starts wearing a blue fedora and punching junkies in the balls:

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

The reason for the new outfit, I can only assume, is a meta-commentary (the kind O’Neil is so fond of) about the essential difference between Batman – at his purest – and Ditko-esque vigilantes like Mr. A, the original Question, and Watchmen’s Rorschach. This also helps explain the faux-hardboiled first-person captions that go with this sequence:

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

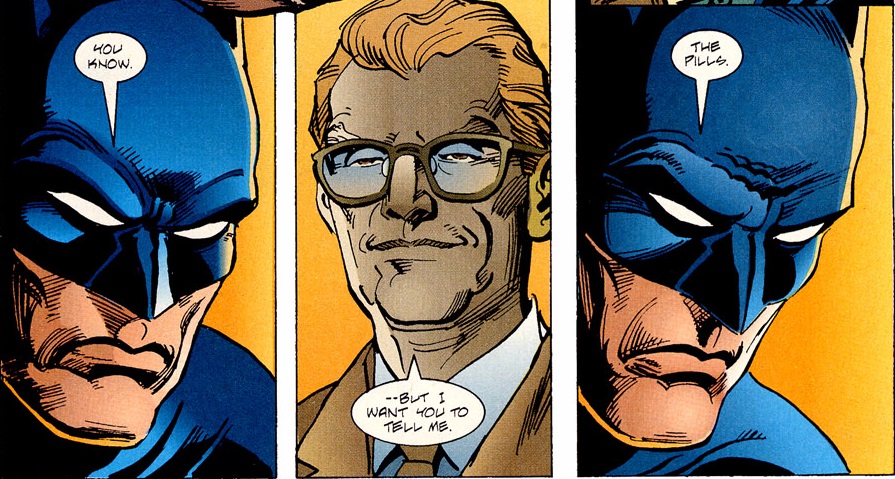

Batman gets seriously addicted to the stuff, so it’s a matter of time before his dealer, Randolph Porter, starts taking advantage of him – basically using the Dark Knight as a compliant thug in exchange for more pills.

It’s not a bad premise. After so many years of watching Batman mistreat dealers and addicts, ‘Venom’ puts a new spin on the series’ anti-drug message by showing the Caped Crusader going through the motions himself. There is something striking about seeing the usually confident, in-control Batman in such a submissive position…

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

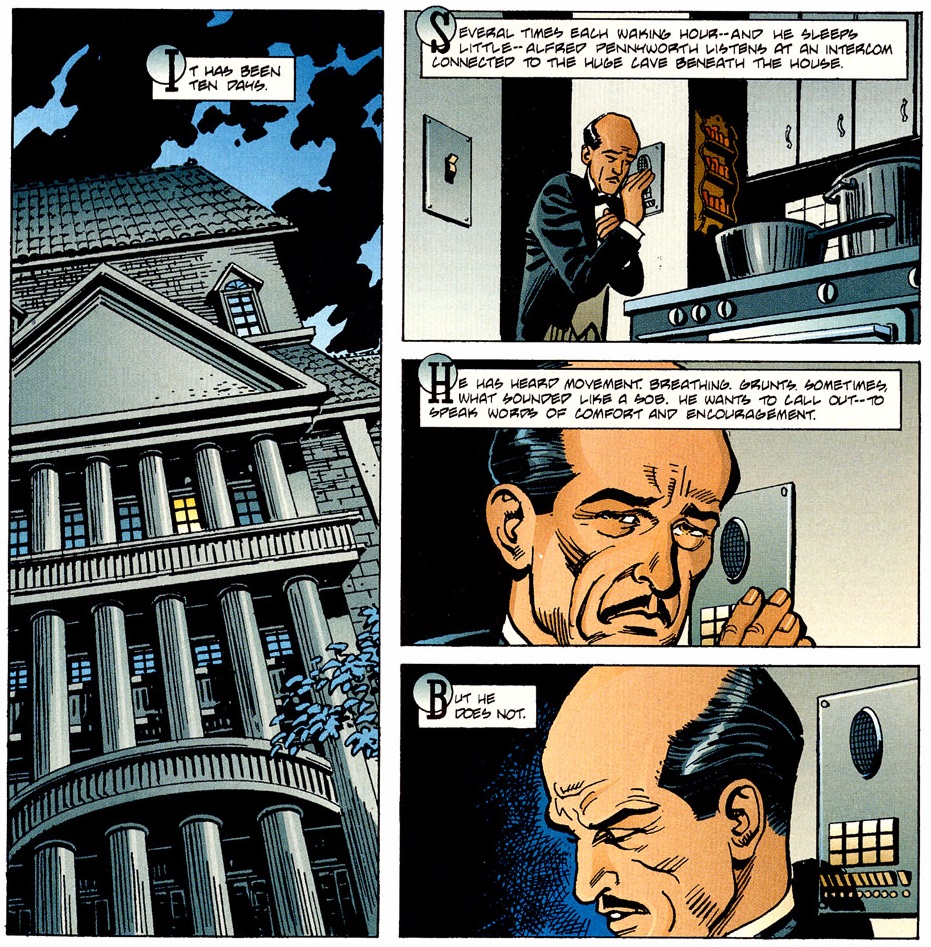

The core sequence in the book takes place when Batman finally realizes he has to break out of his condition and decides to go cold turkey, like Gene Hackman in The French Connection II. He locks himself in the Batcave for a month and tells Alfred Pennyworth not to let him out no matter what.

While Bruce’s whole ordeal feels utterly unrealistic, we are treated to a few touching scenes from Alfred’s point of view that capture what it’s like to have somebody close to you going through such a process…

Legends of the Dark Knight #18

Legends of the Dark Knight #18

Because we don’t see what goes on in the Batcave during that month (except for a couple of animalistic flashback images, later on), ‘Venom’ lets our imagination fill in that terrible gap. All we really know is that during this period Bruce grew a mean, Alan Moorish beard…

Having regained his sobriety, in the final issues Batman travels to Latin America to kick the ass of his former dealer and of General Slaycroft, who has been working with Randolph Porter (in a clear allusion to the armed forces’ involvement in drug smuggling in Vietnam and Nicaragua).

‘Venom’ has a good reputation among many Batman fans, perhaps because it occupies an interesting place in continuity, as a precursor to Knightfall (moreover, years later O’Neil did a spiritual sequel to this arc in Azrael #36-39), or perhaps because it features a number of memorable pulp adventure set pieces, like when the Caped Crusader throws a fridge out of a window to stop a car, when he parachutes into the island of Santa Prisca from an exploding plane, when he fights for his life against sharks, or when he has to come up with a clever escape from a particularly contrived deathtrap.

Unfortunately, though, most of the comic is clumsily executed. Denny O’Neil is not a subtle writer and the art team of Trevor Von Eeden (layouts), Russel Braun (pencils), José Luis Garcia-López (inks), and Steve Oliff (colors) somehow never give the material enough style to compensate for the script’s bluntness. The sight of Batman crying or punching through a phone booth’s glass after talking to Alfred should’ve been powerful moments, but instead they come across as kind of awkward.

Take the ‘terribly acted’ scene, early on, when the Dark Knight tells Randolph Porter about his daughter’s death. I get it that Porter is supposed to be callous and self-centered, but his nonchalant depiction feels completely off – at the very least, Batman should react to such an odd, caricatural behavior… Or take the subplot about General Slaycroft and his abusive relationship with his son, which feels like a lame remake of the Musto father-son dynamic in O’Neil’s The Question… And don’t even get me started on all the lazy clichés, from the openly racist, homophobic, misogynistic right-wing villains to the underwritten female characters who are just there to be the object of exploitative violence.

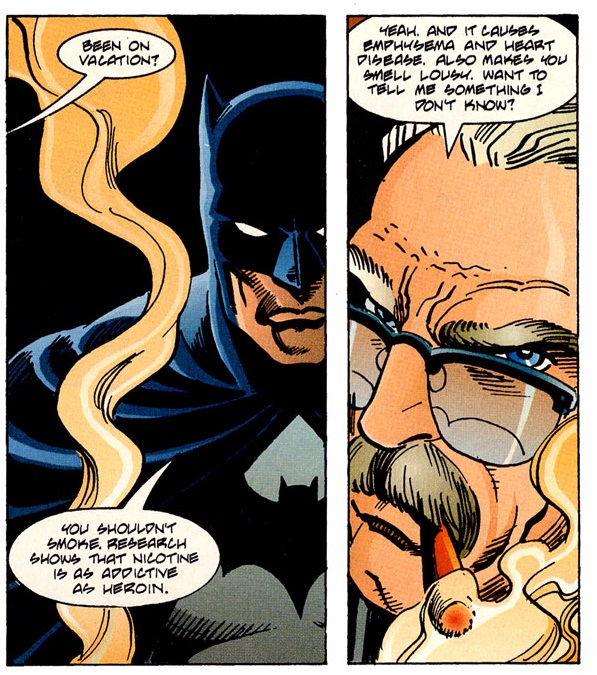

The discourse on drugs isn’t O’Neil at its best either, even if he tries to bring in some complexity by branching out and commenting on other addictive substances:

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

Legends of the Dark Knight #17

The whole thing about Batman becoming a bulky jock who no longer likes to read feels especially forced… It could be explained as Bruce feeling too restless and unable to concentrate, but ‘Venom’ shows it as a radical shift in personality, with him explaining to Alfred that he is ‘passed the need to read’ before going on a rant against the ‘weaklings.’ I get it that his drug is eventually revealed to have been designed with the purpose of creating obedient soldiers, but there are less goofy ways to convey this without going the ‘dumb bully’ route (fortunately, this side effect had been removed by the time Bane became addicted to venom in Knightfall).

If you want a truly nasty Batman story about drug abuse – one that goes for gritty realism without skimming on the action – I would instead suggest a comic that came out the following year: ‘The Black Spider’ (Shadow of the Bat #5, cover-dated October 1992), written by my favorite Batman writer, Alan Grant.

Shadow of the Bat #5

Shadow of the Bat #5

I guess it was a matter of time until the drug-obsessed Grant had a go at the Black Spider. Created by Gerry Conway and Ernie Chua way back in 1976 (Detective Comics #463-464), the Black Spider was a character built around drugs from scratch… An ex-junkie-turned-vigilante on a deadly crusade against the heroin trade, Eric Needham had adopted the Black Spider persona in order to go after superflies (because in Gotham everybody loves masks and animal puns). Also, as was typical of costumed characters with the word ‘black’ in their name, he was dark-skinned:

Detective Comics #464

Detective Comics #464

The original two-parter tale was pretty by-the-numbers. Ernie Chua’s art tends to be slightly more than serviceable and Gerry Conway basically wrote a (more focused) variation on the Punisher, putting Batman in the same position he had previously put Spider-Man (i.e. that of having to defend the criminals he despised against someone who was doing an extreme version of his vigilante crime-fighter act). The sequel, ‘Night of Siege’ (Batman #306), was equally forgettable.

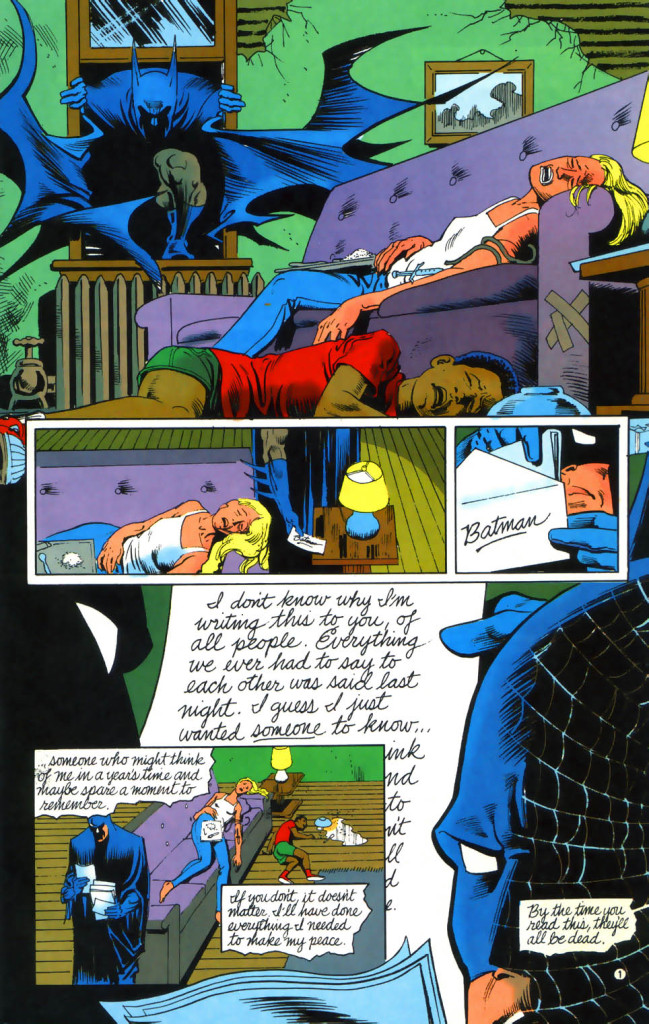

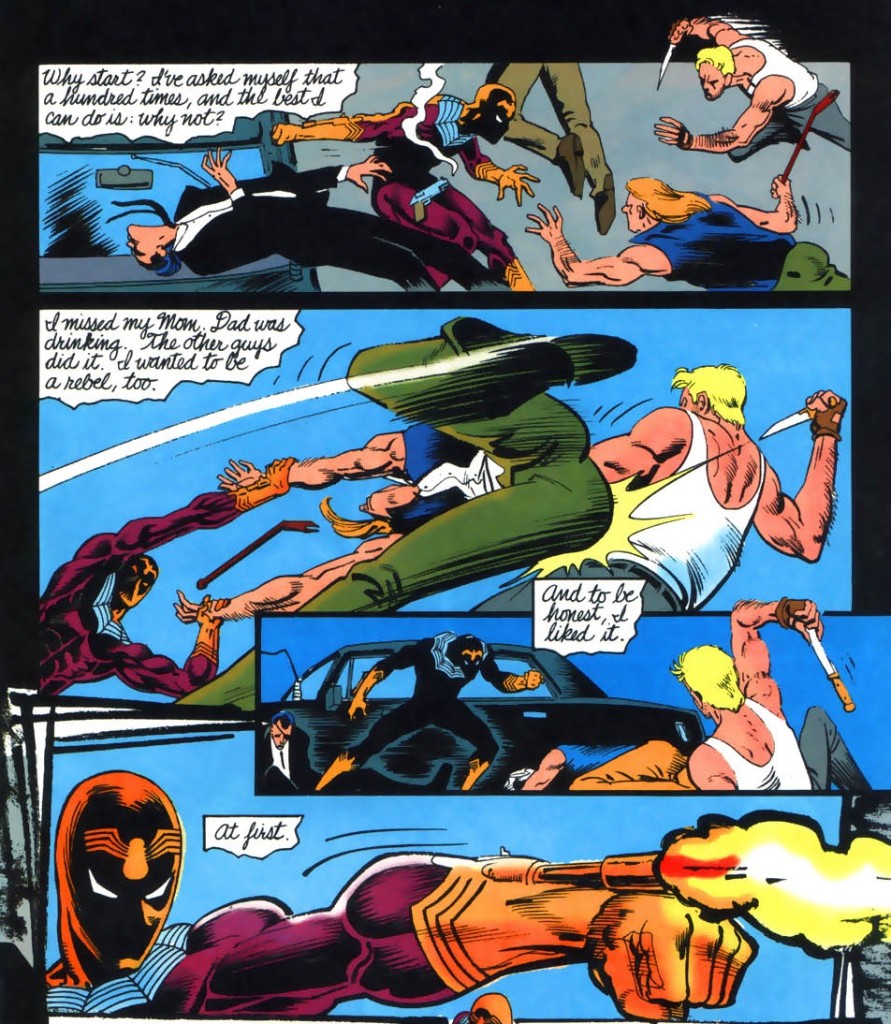

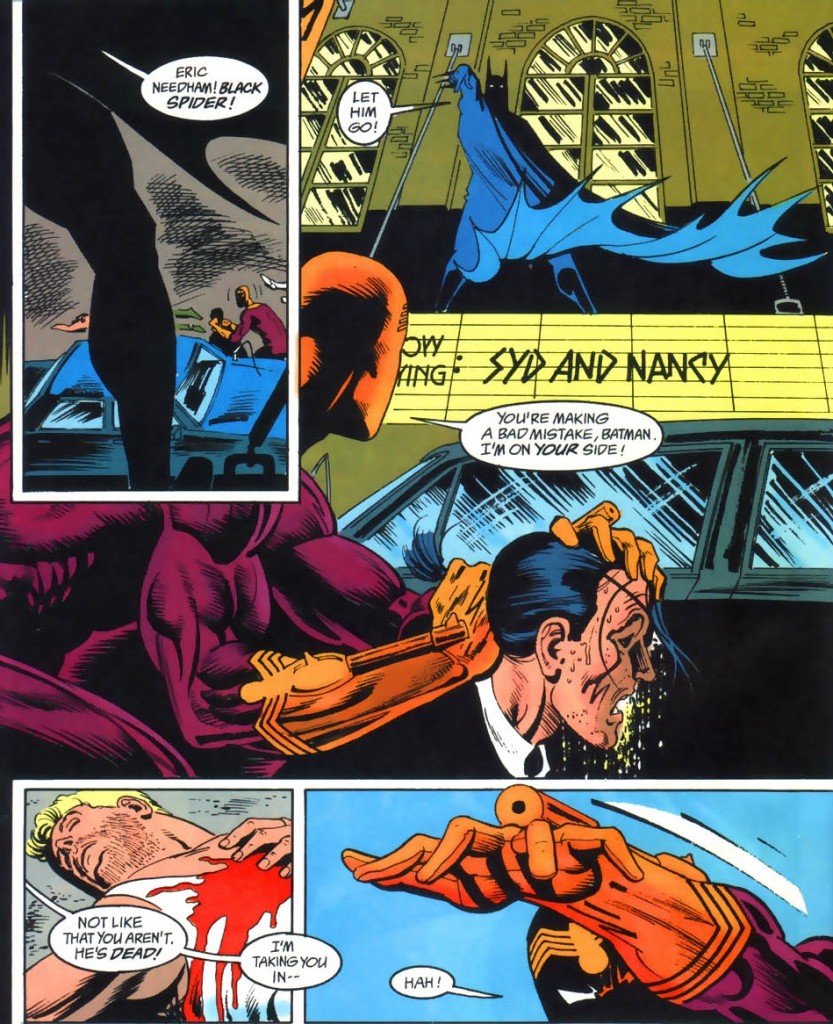

By contrast, Shadow of the Bat #5 is damn hard to forget. The issue pulls no punches: when Eric Needham realizes his former girlfriend is back to shooting smack while raising their kid, he goes on an even more brutal murder spree… Although the Black Spider wears a typically absurd costume, this time there is no effort to disguise the story under a superhero tale. It’s just a bleak affair, full of personal tragedy and self-destruction. And along the way we get Needham’s thoughts on drugs and addiction in the form of a letter addressed to the Dark Knight:

Shadow of the Bat #5

Shadow of the Bat #5

Batman doesn’t save the day in the end – it’s just that everyone dies horribly except him. Man, this has got to be one of the most depressing Batman comics of the 1990s… (It’s certainly up there with Alan Grant’s Detective Comics issue about trash!)

This doesn’t mean it’s not a thrilling read. After all, part of the general appeal of Grant’s comics is precisely the overblown pathos and hysteria. And like many of his best works, Shadow of the Bat #5 benefits from his three greatest collaborators: artist Norm Breyfogle, colorist Adrienne Roy, and letterer Todd Klein, who compellingly convey the characters’ agony and desperation while providing the dynamic pace that the story requires:

Shadow of the Bat #5

Shadow of the Bat #5

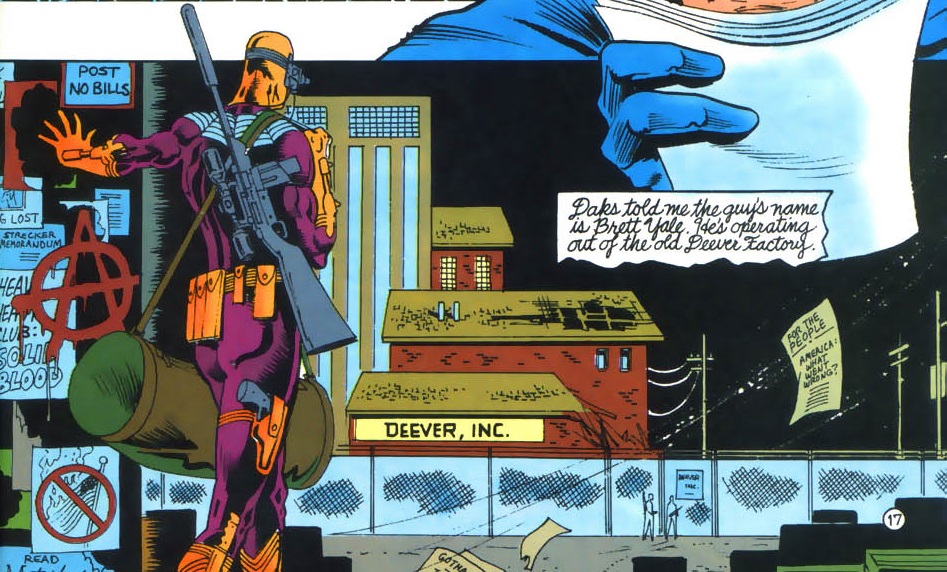

You caught the Syd and Nancy reference? That’s not the only background nod! The issue is packed with allusions to the social context that pushes people towards drug consumption, from economic hardship to anxiety-inducing news stories and conspiracy theories (like the Strecker Memorandum)…

Shadow of the Bat #5

Shadow of the Bat #5

The point of the comic is that addicts are victims who should be helped rather than punished. Instead of judging them, everyone should take into account how easy it is to cave in to all sorts of impulses we need to keep in check, since temptation and addiction are all around us. As the Black Spider puts it, ultimately we’re all addicts, as each of us clings to whatever can relieve life’s pains (‘If it’s not drugs, it’s power, or money, or love… or hate.’). Our outrage should therefore be reserved for pushers who exploit those urges.

I think this results in a more powerful statement than the one in ‘Venom.’ Rather than showing us that Batman can potentially become an addict, Shadow of the Bat #5 argues that perhaps he is already an addict (if nothing else, he is addicted to the rush of being Batman) just like everyone who is trying to ‘fill that gaping hole in the center of ourselves.’