When I’m not compulsively watching spy shows on TV, spy fiction tends to occupy a sizeable portion of my reading time, so I thought I’d share a few impressions on a couple of novels that approach the genre in very different ways:

54

(Wu Ming, 2002)

“ITALIAN SOLDIERS!

The Slovenian people have launched an inexorable struggle against the occupying forces. Many of your comrades have already fallen in that struggle. And you will go on falling day after day, night after night, for as long as you remain tools in the hands of our oppressors, and until Slovenia is liberated!”

54 aims straight at so many of my pleasure centers: it’s a kaleidoscopic Cold War epic, largely set in the 1950s (in the titular year) and starring, among others, Hollywood actor Cary Grant, who gets assigned by MI6 with a mission to woo Marshall Tito, pulling communist Yugoslavia further to the West.

The book zooms in on a variety of perspectives and voices, from Grant’s Palm Beach mansion to a working-class bar in Bologna, linking up the stories of very different people in very different places (there are even a few chapters written from the point of view of a television set, in what is probably my favorite subplot). If at one point you’re following revolutionaries in divided Trieste, the next pages may be set in Bristol, or Moscow, or perhaps focus on the underworld of organized crime emerging in Naples under the command of Lucky Luciano (the real-life gangster whose fascinating saga was chronicled in Francesco Rossi’s impressive 1973 film named after him, which is basically Italy’s answer to The Godfather), yet it all gradually comes together.

Despite the many detours and occasional esoteric debates about postwar Italian and Balkan leftist politics (which I actually can’t get enough of!), there is plenty of overlap with the sort of material that usually pops up in Gotham Calling. After all, much of 54 tells the type of middlebrow international intrigue thriller that Cary Grant could’ve played in, halfway between Notorious and North by Northwest (of course, it helps that I can perfectly hear his specific tone and accent in every line of dialogue). The second half of the book does meander a bit, but it ultimately culminates in one hell of an action scene.

Moreover, Wu Ming – a collective of Italian writers – wonderfully capture Grant’s larger-than-life charisma and the idiosyncratic ego that must’ve come with it:

“How astonished he had been, in the late thirties, the man of the new century. Astonishment went hand in hand with awareness: who had never yearned for such perfection, to draw down from Plato’s Hyperuranium the Idea of ‘Cary Grant’, to donate it to the world so that the world might change, and finally to lose himself in the transformed world, to lose himself never to re-emerge? The discovery of a style and the utopia of a world in which to cultivate it.

Meanwhile, there was an Austrian dauber out there winning a career and followers, whose speeches hit the hearts of the Volk ‘like hammer-blows’, and a distant clang of weapons heralded the worst: the clash of two worlds.

Against the world of Cary Grant, the dauber had finally lost with dishonour, in a puddle of blood and shit.

Without a doubt, the Russian winter was partly responsible, but one thing was certain: the New Man, at least for the time being, wouldn’t be having to tuck his trousers into two-foot-high leather boots to march the goose-step.

The New Man, if there was such a thing, would be reflected in Cary Grant, the perfect prototype of Homo atlanticus: civil without being boring; moderate, but progressive; rich, certainly, even extremely rich, but not dry, and not flabby either.

Even some of the most vehement enemies of capitalism, of America, of Hollywood, were willing to concede that the baby was one thing, the bathwater quite another.

Cary Grant, born a proletarian and with a ludicrous name to boot, had defied fate with the ardour of the best exemplars of his class. He had denied himself as a proletarian, and now he was bringing dreams to millions. If one individual could achieve it, there was no reason why the rest of the working class shouldn’t have it as well.”

Although I quite like the passage above, and some of the others, on the whole I can’t say I’m entirely in love with Wu Ming’s writing. The prose tends to feel too didactic for my taste and the dialogue is full of heavy-handed (and sometimes repetitive) infodumps, with characters saying stuff like ‘as you well know’ and ‘as you have mentioned,’ or awkwardly name-dropping famous people and situations just for our benefit.

I realize not every reader will be as familiar as I am with the era’s geopolitics and regional culture, but there are many ways of conveying information… John le Carré, for instance, often had lengthy, talky briefing scenes with characters carefully explaining this sort of stuff to each other, but he always figured out witty ways of presenting things. Rather than a chore in the name of a necessary set-up, those moments of exposition were absorbing and entertaining by themselves.

And le Carré isn’t the only alternative. At one point, in a bit of tongue-in-cheek intertextuality, Cary Grant starts reading Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale and, although his view is pretty dismissive of that novel, the contrast with the quoted excerpts does not really help. I’m not the biggest Fleming fan but, in just a few sentences, his style comes across as much tighter and incredibly gripping compared to most of 54.

I’m also a geeky, pedantic nitpicker, so I’m not fully convinced about some of Grant’s reactions. After WWII’s propaganda effort, I don’t think he’d need to be persuaded of cinema’s ability to shape people’s dreams and political ideas. And while I think the inclusion of Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief in the narrative is a happy choice (not least because that caper is also about what happened to the former antifascist resistance), I have to wonder how Grant could consider that script an unpromising vehicle for his return to the screen after a hiatus (?), given that this piece of fluff seems perfectly suited to his suave image (especially in contrast to Howard Hawk’s Monkey Business, the very silly comedy he had just starred in). Plus, there is that bit where a Soviet official complains about Hollywood’s ‘dreary war films in which the Russians never even made an appearance,’ showing an ignorance of wartime movies that I suspect the character may share with the authors.

That said, of course the most gratifying way of reading the book is to just accept that it ultimately takes place in an alternate reality, starring a parallel version of Cary Grant, so not every single detail has to match our ‘real’ world. Once I embraced this attitude, I had a lot of fun. Wu Ming’s take on Grant has a particularly amusing payoff in the coda, where a psychiatrist desperately tries to make sense of what the hell is going on in his head!

As the plot tapestry unfolds, 54 becomes an exciting read – and even a thought-provoking one, especially when you consider that it was written against the backdrop of the Kosovo War, 9/11, and Berlusconi’s first return to power, all of which linger in the subtext.

In any case, it’s hard to resist a book that features such a spirited monologue from Tito:

“It happened five years ago. Kardelj, who had had dinner with me that evening, was clarifying the issue of Leninist theory in Yugoslavia, and rejecting the accusations of ‘Trotskyism’ issuing from Moscow. The mirror spied on us from the end of the corridor, our lookalikes copying our every move, perhaps preparing to reproach us. Here we were, well fed and clothed, so unlike the days of the konspiracija. Was it just vanity that dictated the stance that would consign us to history? We discovered (at dead of night it’s inevitable) that there was something monstrous about the mirrors. Kardelj said the mirror is an infernal machine, because it separates the individual from the community, stimulating his petty-bourgeois narcissism. I replied, ‘So how do you trim your moustache, by leaning over puddles?’ adding that, on the contrary, the mirror unites the individual with the community, and its admission into proletarian houses has cemented class pride, that sense of decorum thrown back in the bosses’ faces, ‘We have been naught, we shall be all! We can be, and we are, more stylish than you are!’ It was thanks to that decorum, to that pride, that the war was won.”

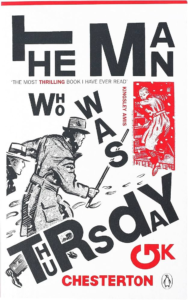

THE MAN WHO WAS THURSDAY

(G. K. Chesterton, 1908)

“The suburbs of Saffron Park lay on the sunset side of London, as red and ragged as a cloud of sunset. It was built of a bright brick throughout; its skyline was fantastic, and even its ground plan was wild. It had been the outburst of a speculative builder, faintly tinged with art, who called its architecture sometimes Elizabethan and sometimes Queen Anne, apparently under the impression that the two sovereigns were identical. It was described with some justice as an artistic colony, though it never in any definable way produced any art. But although its pretentions to be an intellectual centre were a little vague, its pretentions to be a pleasant place were quite indisputable.”

If 54 was chockfull of characters and events unfolding at a breakneck pace, grabbing me with the elaborate plot despite the pedestrian prose, The Man Who Was Thursday managed to pull off an even faster rhythm while consistently spitting out the wittiest turns of phrase. The narrator’s voice was sharp and piercing, like a killer’s knife, and genuinely funny, often making me laugh out loud while frantically turning the pages between cliffhangers.

So much of the joy stems from the dramatic surprises that pop up in every single chapter – hell, in every few pages – so I don’t dare reveal too much about the story, except to say that, like the novels of Joseph Conrad written at the time, at the dawn of the 20th century, it is set in the milieu of terrorists whose radicalism has at least as much do with philosophical fervor as with directly responding to working class living conditions.

For the most part, the book pits secret police agents against the Central Anarchist Council in a narrative that ticks – and even anticipates – many of the beats associated with the James Bond yarns quite a few decades later: the archvillain is a larger-than-life genius running a transnational organization whose facilities are reached through a beer bar table that shoots through the floor into a subterranean vaulted passage lined with guns.. and there are vicious fights as well as plenty of chases involving horses, cars, a balloon, and even an elephant!

That said, G.K. Chesterton ramps up the surrealism, as if already parodying the formula. His intellectual absurdist humor feels like a bridge between Voltaire’s Candide and the writings of Woody Allen, Douglas Adams, or Terry Pratchett (not to mention Stanislaw Lem’s Memoirs Found in a Bathtub), whom he no doubt influenced. The result is simultaneously a rollicking thriller, a slapstick comedy, and a political satire, especially when characters enthusiastically debate their ideas, like in this dialogue with a forerunner of punk nihilism:

“ ‘What is it you object to? You want to abolish Government?’

‘To abolish God!’ said Gregory, opening the eyes of a fanatic. ‘We do not only want to upset a few despotisms and police regulations; that sort of anarchism does exist, but it is a mere branch of the Nonconformists. We dig deeper and we blow you higher. We wish to deny all those arbitrary distinctions of vice and virtue, honour and treachery, upon which mere rebels base themselves. The silly sentimentalists of the French Revolution talked of the Rights of Man! We hate Rights as we hate Wrongs. We have abolished Right and Wrong.’

‘And Right and Left,’ said Syme with a simple eagerness, ‘I hope you will abolish them too. They are much more troublesome to me.’ ”

There may be a twist too many. Near the end, The Man Who Was Thursday, true to the promise of the subtitle (A Nightmare), veers into stranger and stranger territory, jumping from wild farce into outright metaphysical allegory. As much as he reveled in the sense of fantastic chaos that drives much of the book, and although not unsympathetic to the plight of the masses, G.K. Chesterton was still a conservative Christian suspicious of modernity, subjectivism, and anarchy, which increasingly shines through (or, rather, it’s there from the start, but it doesn’t prevent his initial descriptions of revolutionary intellectuals, poets, and zealots from being hilarious… and oddly relatable, still today).

Honestly, I share much less with Chesterton’s worldview than I do with Wu Ming’s political leanings. And yet, at the end of the day, I had way more of a blast with this literary classic, not least because of the sheer pleasure provided by the paradoxes that fill its prose. I can’t resist adding a further quote from the opening paragraph, about the incredible Saffron Park:

“Even if the people were not “artists,” the whole was nevertheless artistic. That young man with the long, auburn hair and the impudent face—that young man was not really a poet; but surely he was a poem. That old gentleman with the wild, white beard and the wild, white hat—that venerable humbug was not really a philosopher; but at least he was the cause of philosophy in others. That scientific gentleman with the bald, egg-like head and the bare, bird-like neck had no real right to the airs of science that he assumed. He had not discovered anything new in biology; but what biological creature could he have discovered more singular than himself? Thus, and thus only, the whole place had properly to be regarded; it had to be considered not so much as a workshop for artists, but as a frail but finished work of art.”