As much as the Gotham TV show pretends that it isn’t the case, if you’re into Batman, you’re likely to enjoy superheroics. Although one can argue that Batman is not an actual superhero because he doesn’t have super-powers (I disagree), his comics are definitely superhero comics. Greg Hatcher really nailed it when he stressed that, no matter how much you disguise their fantastical elements, the core appeal of Batman stories is not their realism, but precisely their potential for escapism. Of course, part of what makes them so cool is the way in which they combine different genres, such as horror and detective fiction, but at the end of the day, what defines Batman comics more than anything else is the science ninja billionaire wearing a cape & cowl to protect his secret identity while punching thematic villains. Also, he sometimes hangs out with Superman.

Regardless of historical and cultural justifications, that stories about crimefighters with silly codenames, outrageous costumes, and supernatural powers became an actual genre is peculiar enough, but the fact that this grew into the most mainstream genre in American comics is insane – especially given the tendency for convoluted, interconnected narratives that span several decades and involve thousands of disparate threads. But this is not to say that they cannot be phenomenal pieces of fiction. Watchmen is a widely known example of a sophisticated superhero comic that is also friendly to readers unwilling to do background research, and there are plenty of others…

Astro City

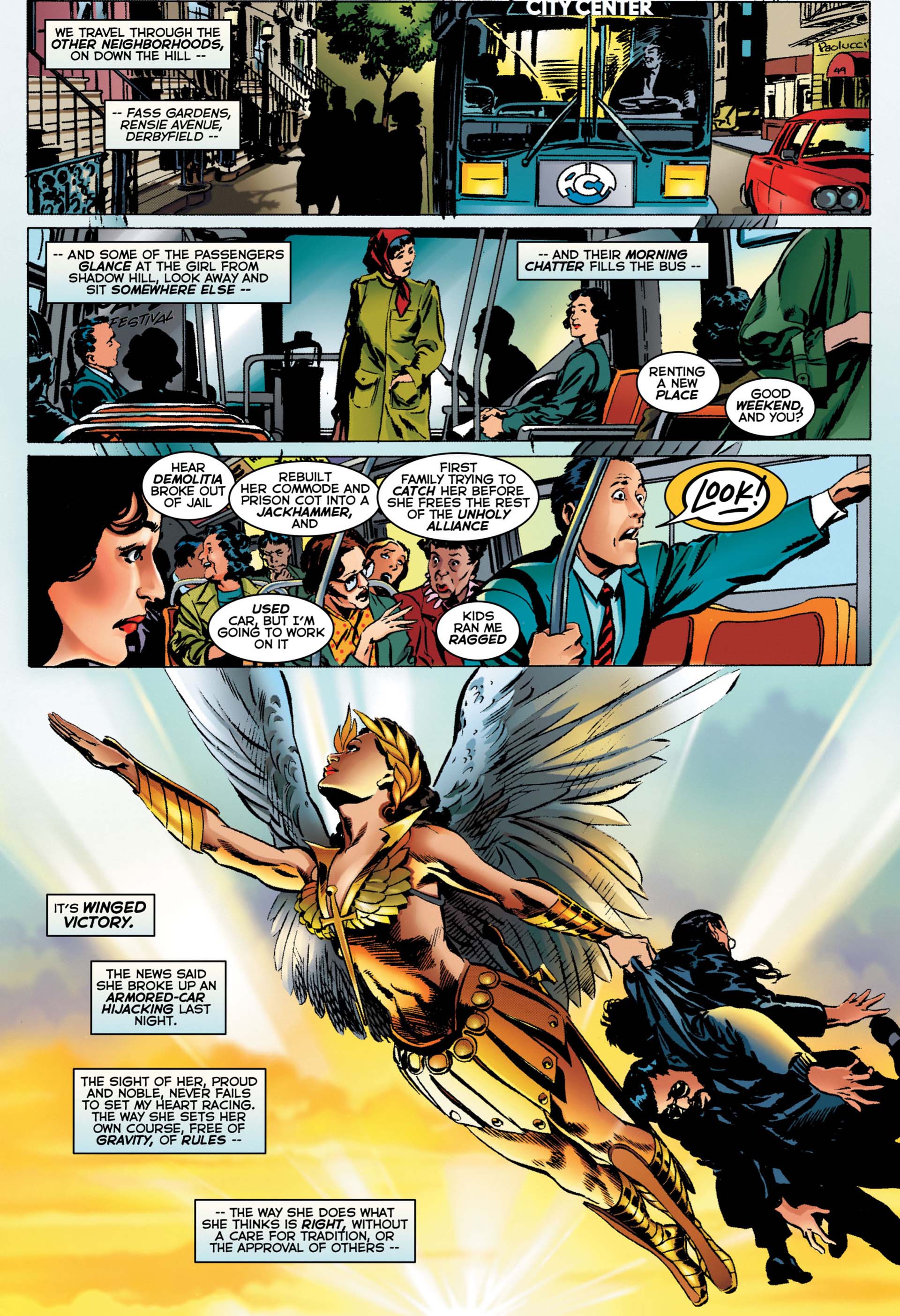

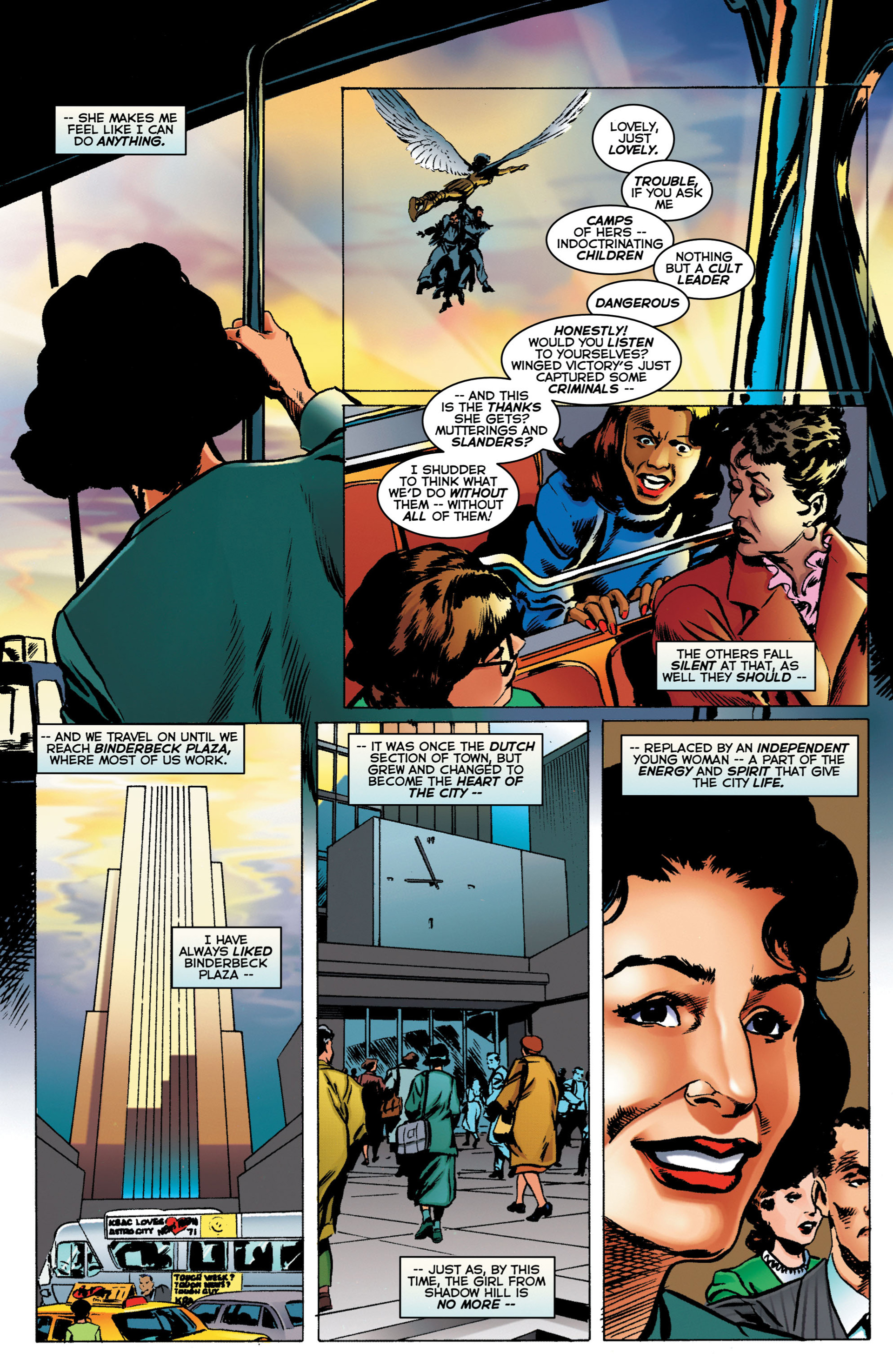

Intelligently written by Kurt Busiek and beautifully illustrated by Brent Anderson (with designs and covers by Alex Ross), Astro City is a long-running series of self-contained superhero stories – or rather, stories set in a city full of superheroes, where the heroes themselves are rarely the protagonists. Played straight, rich in detail, with realistic art, three-dimensional characters, and mature, resonant themes, this is the brightest equivalent of Watchmen. While Watchmen deconstructed the genre by asking what it would be like if superheroes lived in our world, Astro City reconstructs it with a modern sensibility, asking what it would be like if we lived in a world of superheroes. How could journalists fact-check articles about intergalactic battles? How would courts work if invoking magic and shapeshifting aliens were reasonable arguments?

Intelligently written by Kurt Busiek and beautifully illustrated by Brent Anderson (with designs and covers by Alex Ross), Astro City is a long-running series of self-contained superhero stories – or rather, stories set in a city full of superheroes, where the heroes themselves are rarely the protagonists. Played straight, rich in detail, with realistic art, three-dimensional characters, and mature, resonant themes, this is the brightest equivalent of Watchmen. While Watchmen deconstructed the genre by asking what it would be like if superheroes lived in our world, Astro City reconstructs it with a modern sensibility, asking what it would be like if we lived in a world of superheroes. How could journalists fact-check articles about intergalactic battles? How would courts work if invoking magic and shapeshifting aliens were reasonable arguments?

By focusing on the lives of what are usually peripheral characters (the average citizens, sidekicks, small-time villains, collateral damage) and showing how they are touched by large-scale conflicts happening somewhere off page, Astro City manages to capture a genuine sense of wonder often lacking in today’s superhero comics. Busiek and Ross famously used this type of street level point of view to great effect in Marvels, their ode to the Silver Age Marvel Universe, but Astro City comes with the bonus of being highly accessible to new readers. Sure, older fans can enjoy metafictional Easter eggs and homages, but these never get in the way of the stories. And although many characters start off as obvious riffs on famous creations from the Big Two (including a sinister version of Batman, called The Confessor), Astro City is less about commenting on those archetypes than about using them to explore small-scale human facets and quirks.

Catalyst Comix

Taking a radically different approach, Joe Casey sought to revitalize superhero comics not by making them more grounded and relatable, but by pumping up the hard rock stereo. At once old school and postmodern, Catalyst Comix unleashes the genre’s craziness and hyperbole, unapologetically going for relentless, mind-blowing, semi-poetic, Kirbyesque pop art surrealism. Casey opens the book with what appears to be the end of the world, goddamn it, and instead of pulling back for a flashback, he doesn’t let go, gleefully pushing forward with bravado, libido, and loads of exclamation marks! The pages above are from that very first issue, where the Earth comes under attack by a villain described in Casey’s colorful, over-the-top prose:

‘TO GIVE IT A PROPER NAME IS TO SOMEHOW DIMINISH IT. BUT WE’RE GONNA GIVE IT ONE ANYWAY…

IT IS THE ULTIMATE DEATH CONCEPT! IT IS THE FINAL NIGHTMARE MADE TERRIFYINGLY REAL!

THE ONLY WORD TO DESCRIBE IT ECHOES THROUGH THE UNIVERSE LIKE A MINOR METAL KEY, DROP D TUNED CACOPHONY OF CHAOS!

NIBIRU IS RELEASE!

NIBIRU IS DECAY!

NIBIRU IS EXTINCTION!

NIBIRU IS!’

Catalyst Comix tells three separate (but occasionally interconnected) stories. ‘The Ballad of Frank Wells,’ robustly illustrated by Dan McCaid, concerns a powerful superhero exploring alternative paths to save the world, from spiritual enlightenment to political activism (including a hilarious bed-in protest). With quirky art by Paul Maybury, ‘Amazing Grace’ takes place in Golden City, a utopian haven for forward thinkers (‘a socioeconomic theme park’) protected by the eponymous heroine, who has to fight off the sexual advances of a mysterious alien. ‘Agents of Change’ brings together a group of narcissistic superheroes past their prime, trying to regain meaning beyond their dead-end existence of S&M clubs and reality TV shows, rendered by Ulises Farina’s stylish pencils.

Empire

What if, for once, the megalomaniac supervillain actually won? Empire is set in a reality where a Doctor Doom-like figure defeated the local superheroes and successfully took over… and now has to deal with the politics of ruling a ruthless empire while keeping his various conspiracy-prone ministers in check. Every character has a hidden agenda in this chessboard of a story, full of plot twists and shifting perspectives. After years of reading about villains like Ra’s al Ghul wanting to conquer the world (hey, who doesn’t?), it’s refreshing to see such an in-depth exploration of the possible payoff – especially as the comic avoids the temptation to tell a straightforward tale of resistance or hero-driven pushback (a la Final Crisis) and keeps its focus on the despot and his mischievous underlings.

What if, for once, the megalomaniac supervillain actually won? Empire is set in a reality where a Doctor Doom-like figure defeated the local superheroes and successfully took over… and now has to deal with the politics of ruling a ruthless empire while keeping his various conspiracy-prone ministers in check. Every character has a hidden agenda in this chessboard of a story, full of plot twists and shifting perspectives. After years of reading about villains like Ra’s al Ghul wanting to conquer the world (hey, who doesn’t?), it’s refreshing to see such an in-depth exploration of the possible payoff – especially as the comic avoids the temptation to tell a straightforward tale of resistance or hero-driven pushback (a la Final Crisis) and keeps its focus on the despot and his mischievous underlings.

Empire came out around the same time as Mark Millar’s Wanted, with which it shared the overall premise, as well as generous doses of sex and blood. But while Millar buried some cool ideas under a pile of tasteless jokes and repugnant subtext, in Empire Mark Waid crafted an engaging superhero version of the court of the Borgias. Waid seems less interested in transcending or mocking genre conventions than in applying them to a different kind of setting – and he definitely knows what he’s doing, having written tons of great superhero comics throughout his career (including the JLA storyline ‘Tower of Babel’ where Batman comes up with ways to defeat all the major heroes in the DC Universe). And while I’m not a big fan of artist Barry Kitson, his collaborations with Waid tend to bring out the best in him (particularly their clever take on Legion of Super-Heroes). Recently, the duo have returned to the world of Empire through Waid’s innovative comics platform Thrillbent.

Ex Machina

Ex Machina is comics’ answer to The West Wing, only focusing on local politics and with a great sci-fi twist. It’s set in an alternate reality where Mitchell Hundred, after a brief career as a costumed hero, won the 2001 New York City mayoral election. Less a superhero adventure than a political thriller in which the main character happens to be a former superhero, the series engages with several hot topics, from gay marriage to terrorism, as it switches back and forth between backroom discussion of real-world issues and fresh takes on superhero tropes.

Just like in the gender-themed adventure saga Y: The Last Man and in the Iraq War parable Pride of Baghdad, writer Brian K. Vaughan finds an original way to raise thought-provoking points. His plotting is ingenious and the dialogue heavy on profanity, pop culture references, and witty exposition. This, combined with Tony Harris’ photorealistic, cinematic art (which manages to breathe life even into long scenes of people talking to each other in boring rooms), makes Ex Machina feel like a precursor to TV’s Veep, although it veers into darker, House of Cards territory by the end.

Miracleman

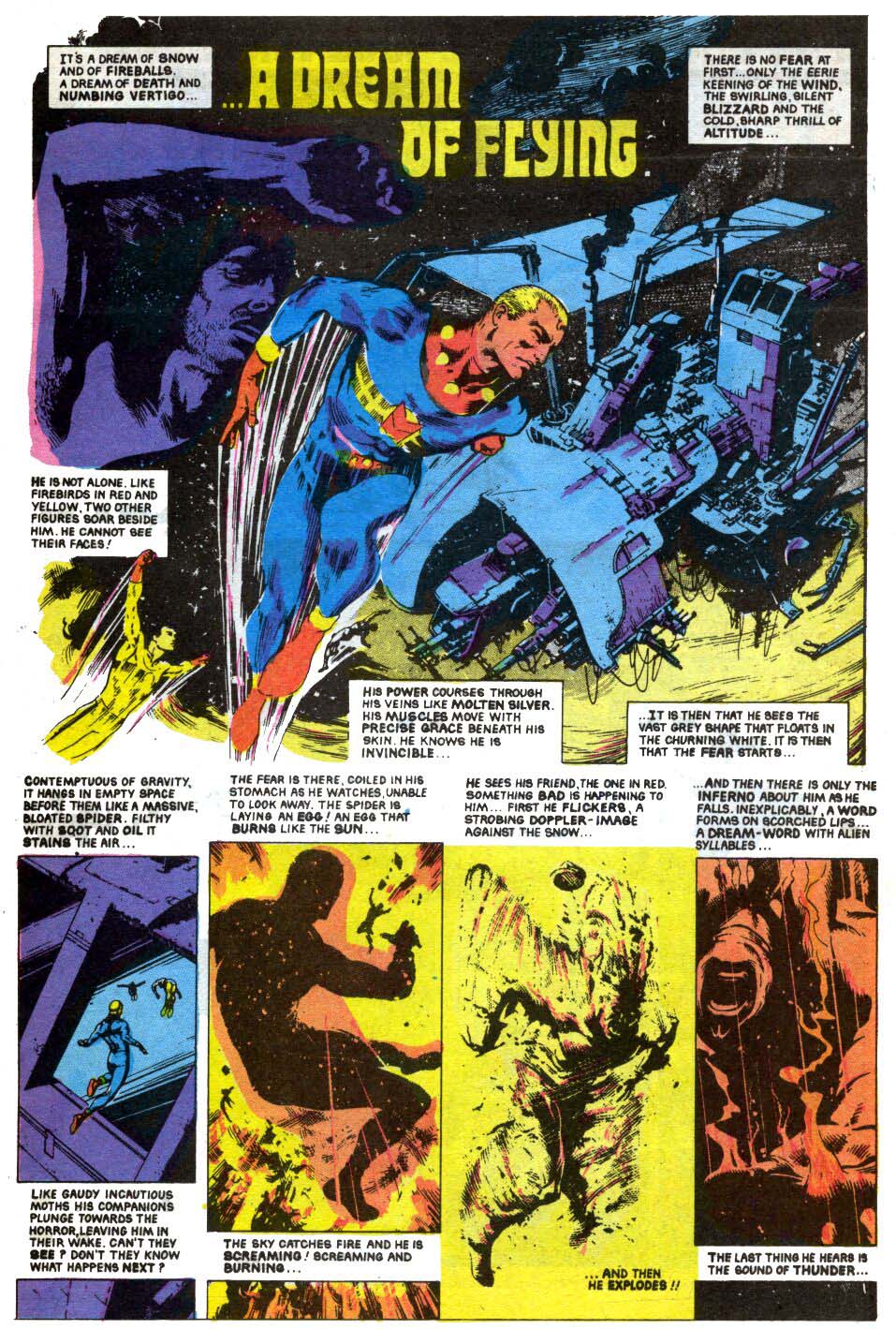

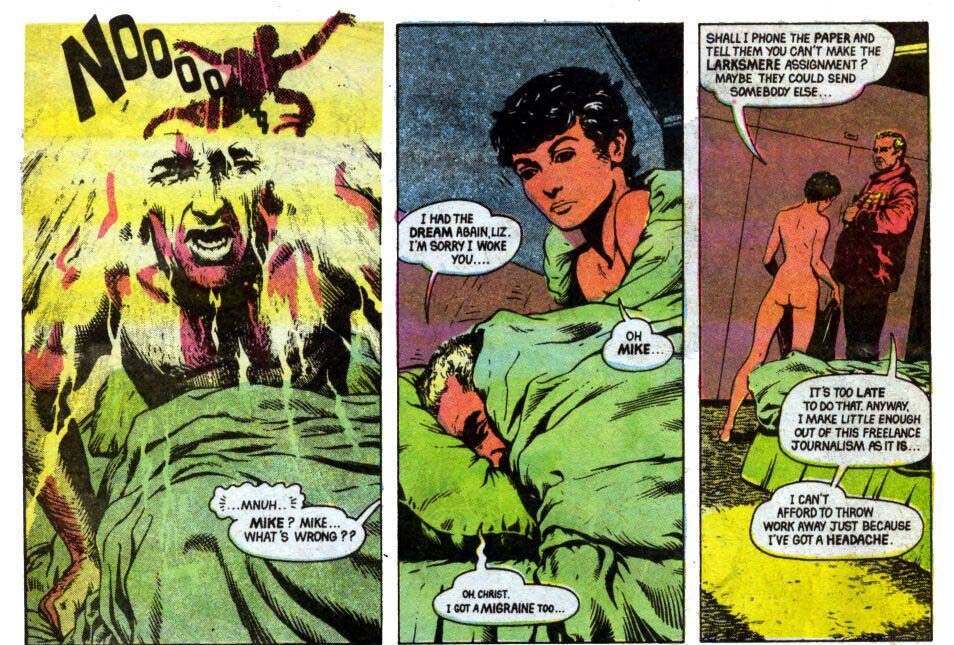

If you think Alan Moore said all he had to say about superheroes with Watchmen, then you desperately need to read Miracleman. The series kicked off as one of the first 1980s’ gritty, revisionist takes on the genre, updating an old British superhero comic (itself a thinly veiled rip-off of Captain Marvel) into Thatcherite reality, but it gradually evolved into something much more ambitious as Moore took advantage of the fact that he was not restrained by shared continuity with other titles and took the story wherever it led him. In a way, Miraclemen (originally Marvelman) mirrors the history of superhero comics in general: starting out as simple tales with naïve archetypes and crude art, turning increasingly mature and engaging with the genre’s implications, and finally taking the concept of superheroes as far as possible by completely reimagining their world. It also includes Moore’s pet themes of transcendence and unconventional sex.

But it’s not just Alan Moore’s show. He was joined by amazing artists, such as Garry Leach, Alan Davis, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben, among others. And after he was done, Moore handed over writing duties to Neil Gaiman, who further expanded the series’ universe and took it in a new, interesting direction. After decades in limbo, Miraclemen is finally back in print, with new coloring, and even some new stories. It’s essential reading for any fan of the genre.