I suppose it is possible to do subtlety in Batman comics. To do it well, even: from Greg Rucka’s nuanced characterization to Grant Morrison’s elliptic narratives; from Dan Slott’s skill at disguising plot points to Ed Brubaker’s occasional flirts with realism… Still, the notion doesn’t seem like a natural fit in a series about a guy for whom the best way to handle problems is dressing up like a humanoid bat and jumping from rooftop to rooftop in order to punch those problems in the mug – and by ‘problems’ I mean insane killers with flashy costumes and explicit themes running through their regular crime sprees.

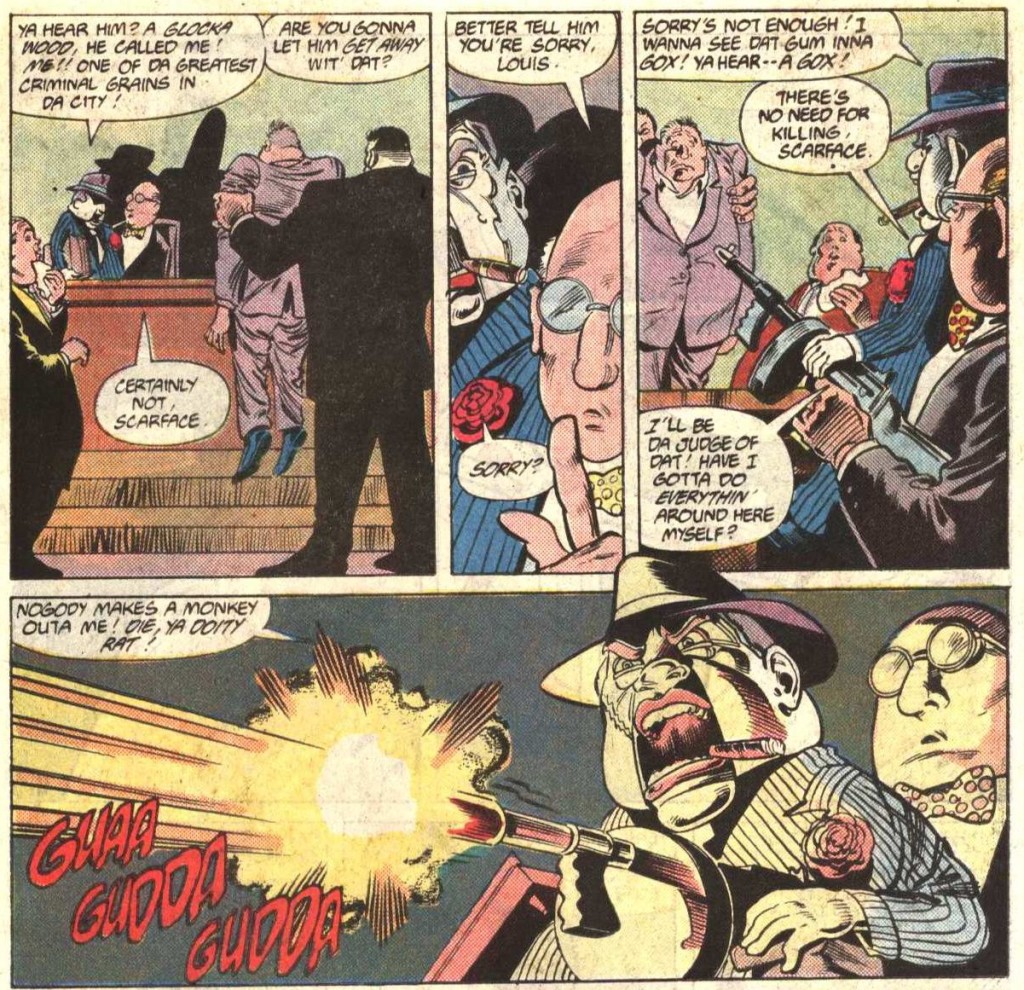

One of the reasons I love Alan Grant’s work on Batman so much is that he unabashedly embraced the visceral appeal of this world, without attempting to soften or hide it. In the hands of this Scottish writer, Gotham City became a springboard for satisfyingly blunt, frantic, outraged, and outrageous stories. Grant’s Dark Knight was often furious, insulting criminal scumbags and the system that spawned them while burning with indignation. Grant’s villains were dangerously delusional or further pushing society off the edge…. or both, like in the case of Scarface, the ill-tempered gangster who was either a psychotic ventriloquist or a demonic wooden dummy with a speech impediment:

Detective Comics #583

Detective Comics #583

After making a name for himself as one of the key voices of the irreverent British anthology series 2000 AD, Alan Grant arrived in Gotham City circa 1988. He penned a stupendous run on Detective Comics (#583-597, #601-621), at first co-written with his regular partner-in-crime, John Wagner, with hyperkinetic art by Norm Breyfogle. In late 1990, Grant moved to the more continuity-heavy Batman title, for which he did around twenty issues (mostly illustrated by Breyfogle) before being given a spin-off series (with various artists), Shadow of the Bat, entirely devoted to his brutal take on the Caped Crusader’s corner of the DC universe. Grant wrote that series until issue #82, in 1999, as well as a bunch of crossovers and specials throughout the nineties. The quality of his output became increasingly uneven, but there were odd gems right until the end.

Along the way, we got all sorts of deliriously tasteless comics, including disturbing tales of cannibalism and more dead kids than in Game of Thrones. From the onset, Alan Grant filled his scripts with macabre ideas and characters. Some of these caught on, like the serial killer Victor Zsasz or Jeremiah Arkham, the asylum director whose strategies for dealing with patients were dubious at best. Other characters remained mostly confined to Grant’s stories (perhaps because they were too eccentric to appeal to more reasonable writers), like the deranged debt collector Tally Man or the death-obsessed Mortimer Kadaver:

Detective Comics #589

Detective Comics #589

As you can probably tell by now, there is a strain of dark humor running through these comics (particularly the ones set in Arkham Asylum, a recurring location), but it never fully takes over the material. While Grant’s most purely comedic series can be quite dumb and lowbrow (Lobo, Robo-Hunter, his final arcs on The Demon), in his Batman work the humor tends to match the overall tone, set somewhere on the border between amusingly silly and downright sinister.

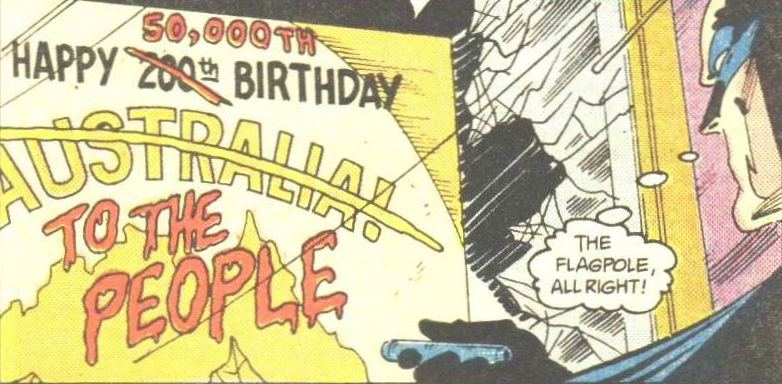

Indeed, the flashes of comedy shouldn’t be mistaken for irony. Like I said, there is an earnestness and committed bluntness to Alan Grant’s writing, whose raw power sometimes approaches that of Scottish anarcho-punk. Himself a self-professed anarchist, who in the mid-90s became a follower of Neo-Tech, Grant often treated Batman comics as a vehicle for his takes on philosophy and politics (by ‘vehicle,’ I mean bulldozer). This was especially the case in comics featuring his beloved creation, the vigilante Anarky.

Grant would often choose a specific theme and build the whole story around it, like an after school special. That month, every single character would end up engaging with the same topic, whether it was the notion of violence as entertainment (Detective Comics #596-597), the proliferation of garbage (Detective Comics #613), or hero worship (Batman #466). He occasionally came up with neat ways to frame the debate: in Shadow of the Bat #72, a writer goes around asking Gotham citizens about the meaning of life while Batman pursues a particularly grisly case; in Shadow of the Bat #77, a teacher delivers a lecture about Darwin’s theory of evolution to the corpses of his dead students.

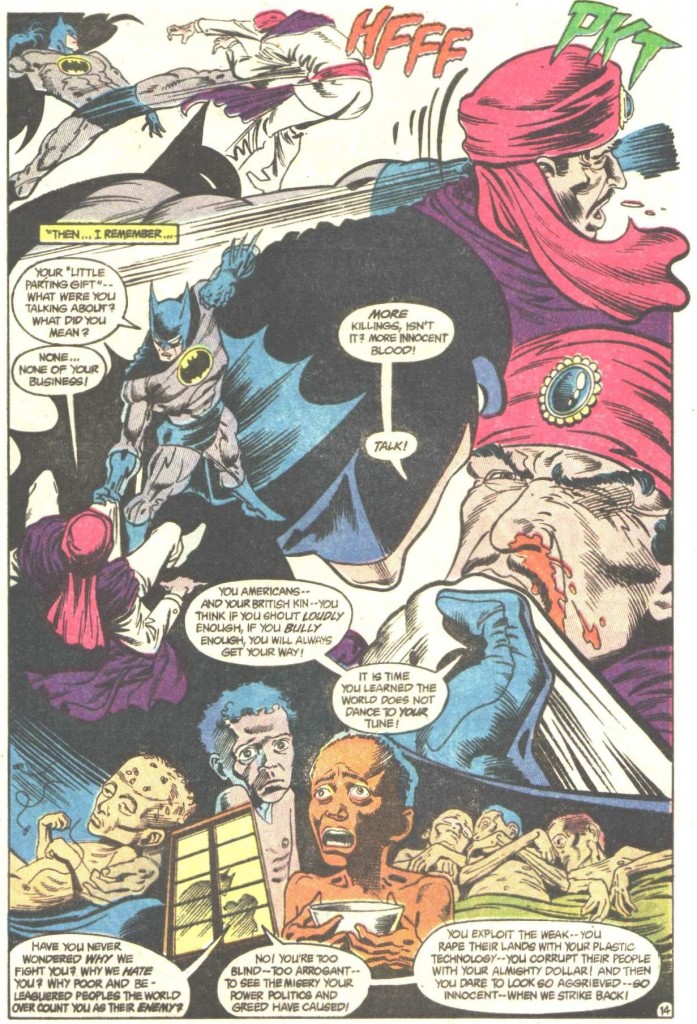

At his best, Alan Grant was able to blend his political and philosophical points into the series’ off-kilter vibe, but he didn’t always manage to avoid sounding preachy. One tale that bravely tried to walk that fine line was ‘An American Batman in London’ (one of several comics in which Grant took the Dark Knight to the UK). This wall-to-wall action romp starts out just like so many other stories featuring cardboard jihadi terrorists, yet halfway through it confronts Batman and the readers with the other side’s perspective:

Detective Comics #590

Detective Comics #590

The issue – cover-dated September 1988 – interestingly tries to offer a counterpoint to the many thrillers about Muslim villains coming out at the time (and still common today), with their one-sided, Islamophobic discourse… It also places this trend in a long tradition of simplistic public discourse about terrorism by setting the tale during Guy Fawkes Night. Yet the comic can be seen as becoming too much of a straightforward polemic, losing sight of what makes Batman stories so special.

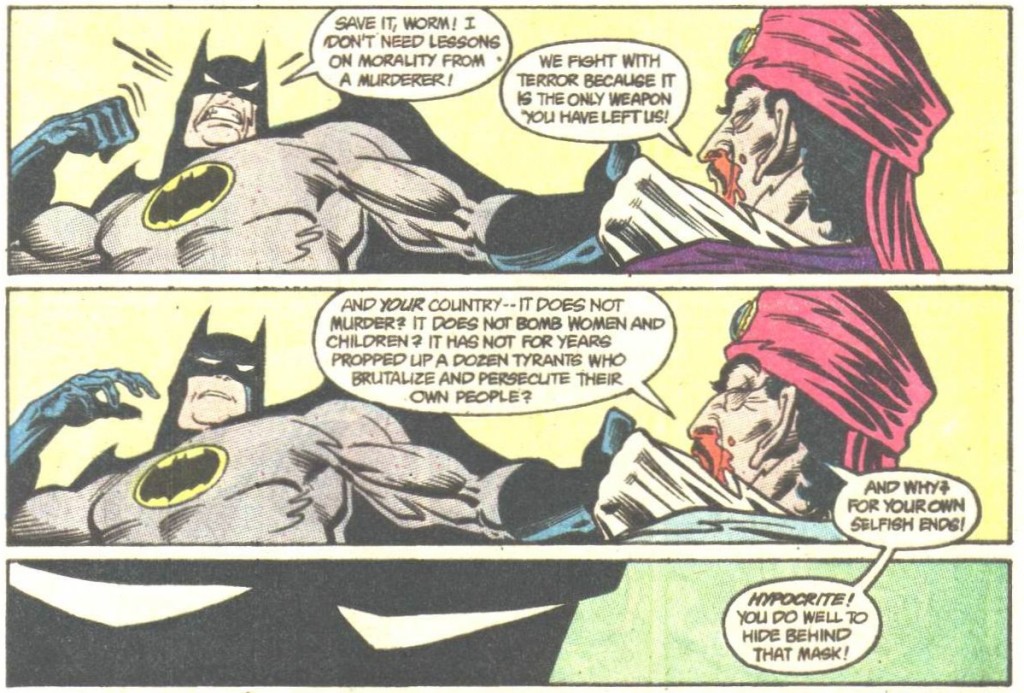

The following issue, ‘Aborigine,’ was also pretty heavy-handed, although I would argue that it incorporated its critique of racism and colonialism in a more appealing way. In that swift-moving adventure, Batman faced a badass Indigenous Australian armed with spears and boomerangs on a bloody quest to recover an artifact from a Gotham exhibition. The result is goofy and weird and arguably offensive on many levels, but it’s also a lot of fun, even if Batman barely does anything significant in the story other than realize that not even he can stand in the way of historical justice…

Detective Comics #591

Detective Comics #591

I’m also a fan of that 1995 one-shot in which Alfred and Nightwing travel to the United Kingdom to stop a group of Eurosceptic aristocrats from staging a coup – a comic that feels oddly prescient in the current Brexit era (even if the villains’ plan involved blowing up the Channel Tunnel, so that British insurance companies would get hammered, the stock market would collapse, the pound would nosedive, and they could then basically buy the country… a slightly riskier route than the one the UKIP ended up taking!).

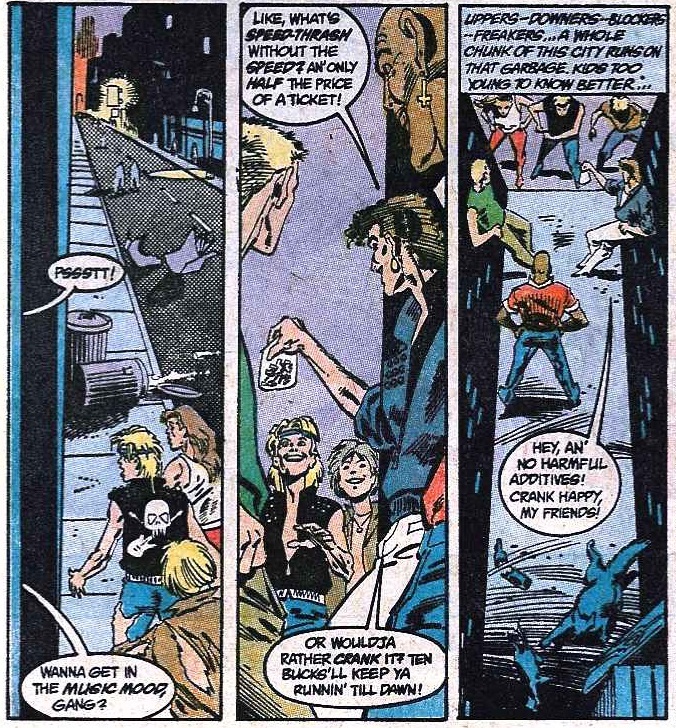

One topic kept coming up more than any other one in these comics: drugs. You can pick any random issue written by Alan Grant and starring the Dark Knight and it is more than likely to feature illegal substances and psychotropic trips at some point, often at the core of the story. Perhaps it’s not so surprising, given that Grant was living in the Scottland that gave birth to Trainspotting, but in any case you can see this trait right from the start: Grant’s very first issue was about an outbreak of designer drugs called Fever (for feverol trinitrite), highly addictive pills that gave users a power rush. From there, Grant went on to write about every weed and opiate in the book. Detective Comics #611 even introduced a new cocaine derivative, called ‘super-crack.’

Seriously, Grant’s Gotham City was overflowing with narcotics…

Detective Comics #608

Detective Comics #608

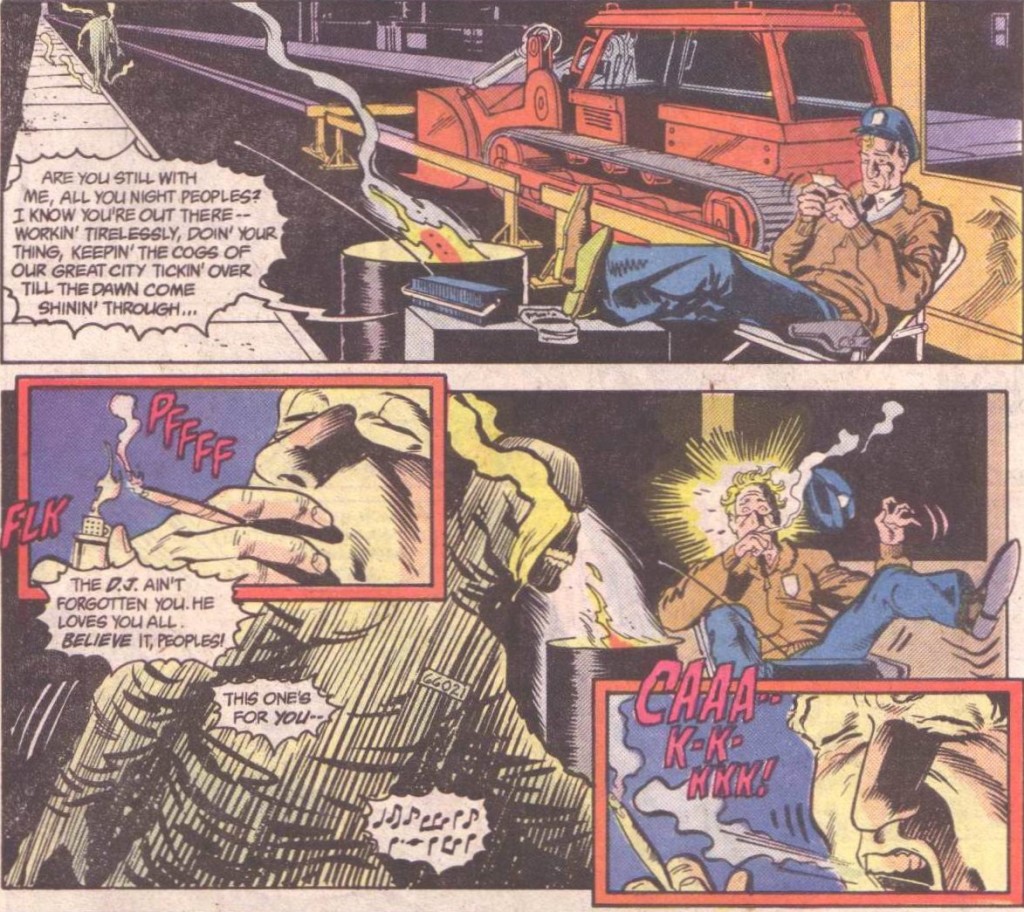

Even background characters couldn’t get enough of the stuff:

Detective Comics #589

Detective Comics #589

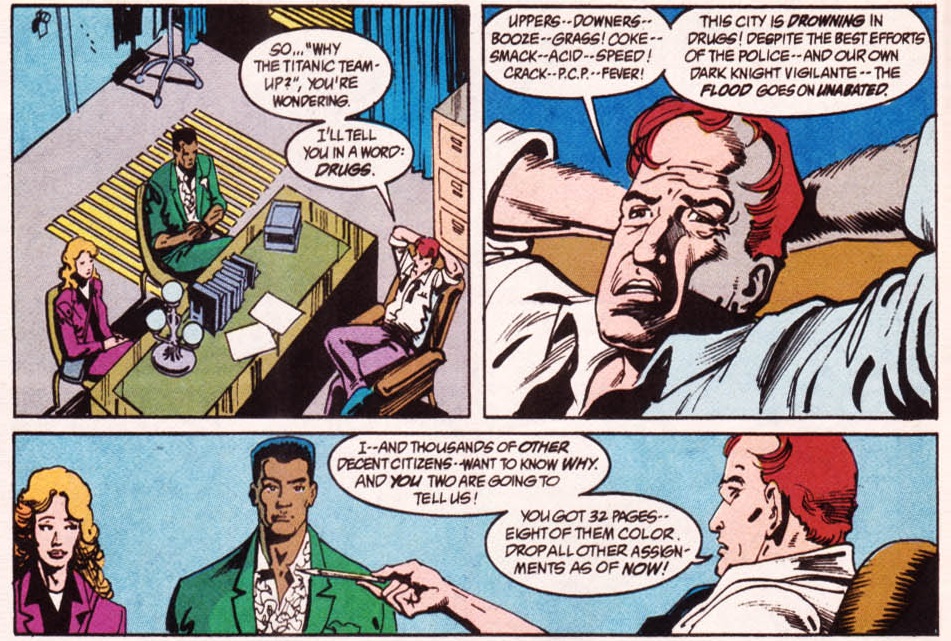

We got to follow reporters Vicki Vale and Horten Spence around, as they were actually assigned a news story on this issue:

Batman #475

Batman #475

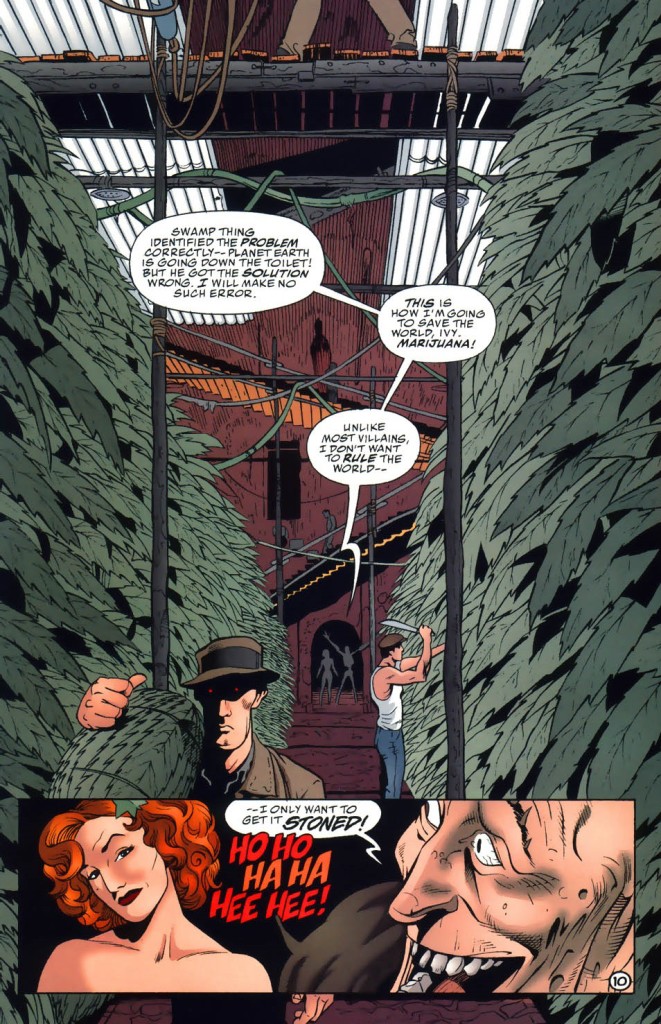

Alan Grant’s drug comics have that mix of grim outrage and shamelessly trashy entertainment you find in exploitation movies like Coffy and Class of 1984. It’s not just that the Caped Crusader spends much of his time beating up dope pushers and dealers, it’s the fact that they can be as hysterically over-the-top as everything else. In Detective Comics #608, punk rock star Johnny Vomit gets his ass kicked for smuggling smack in his guitar. In Shadow of the Bat #32, Scarface ruthlessly goes after a competing drug lord by cutting his heroin with strychnine, thus killing dozens of helpless junkies in order to ruin the guy’s reputation. Later, there was an unbelievably ridiculous storyline in which the Floronic Man, after having been beheaded at the climax of Mark Millar’s Swamp Thing run, came back as a grass-themed supervillain:

Shadow of the Bat #57

Shadow of the Bat #57

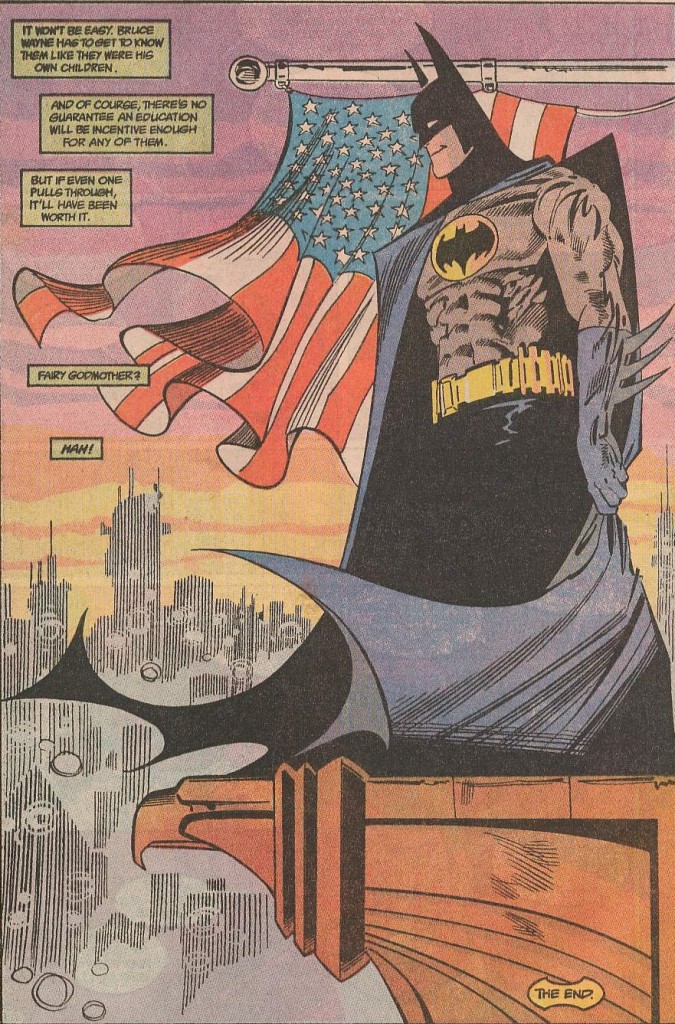

What else can I say? I wouldn’t want all my readings to feel like this, but Alan Grant’s works are the kind of pure, uncut stuff that gets me high on Batman comics (just to stick to Grant’s favorite imagery)… They can be hectic and gritty and borderline sadistic. They can feature a ham-fisted lecture or gloriously awful junk fiction. They can show the Dark Knight at his coolest, kicking butt and taking names, or just wrap up with Batman downtrodden by the cruel society around him, having let another villain get away or yet another kid die in vain. Or maybe you’ll get a corny final splash with the Caped Crusader framed between an eagle’s head and a US flag while thinking about the importance of making sure every child has a chance, regardless of background. In any case, you can be damn sure you’re in for a ride, with verve and panache to spare. It’s like every page is screaming: if you want subtlety, fuck off and go look for it somewhere else!

Detective Comics #614

Detective Comics #614

NEXT: Slavery.

I remember a comment you made about how horrible it was to have been a teenager during the 1980s (which I was). Until I read your words, I thought it was just my miserable personal experience since most everyone around me seemed so damned well adjusted; my classmates were destined to be just like their equally hideous parents, and as Paul Newman’s Lew Harper would say in 1966’s HARPER, “Cream and bastards rise.” Yes, the mid-to-late 1980s were among the worst years of my existence.

Anyway, the Batman comics of that garish and ugly decade provided a bit of a respite–a comforting shelter, if you will–as I tried to make sense of an increasingly rotten world, or, more specifically, the putrid home and school environment in which I found myself at that time. Grant-Breyfogle’s Detective Comics run provided me with an escape while at the same time a mirror into that unpleasant time frame. Those Grant-Breyfogle tales are surrounded by garish–that’s the operative word of the 1980s–adverts while the stories themselves reflect the cold, cruel, drug-addled world of the mid-to-late 1980s.

I always looked forward to what messrs Grant and Breyfogle would dole out each month. They were continuing the foundation formed by O’Neil and Miller before them but it was all very much of its time–or any time that one might have, as The Byrds sang in “Turn! Turn! Turn!”, “refrained from embracing.” It is for these reasons that Grant-Breyfogle Detective resonates with me.

I hope they realize what an effect those stories had on the generation that read them.

The mid-to-late 1980s were a horrible time but, as it is often the case, they therefore produced some amazing counter-culture. Most of my favorite comics and music came out around then, clearly reacting against the surrounding politics, society, and mainstream culture. They were not just a reflection of the garish world around them, but also a funhouse mirror showing us that even the things we had been told to accept as right could ultimately be seen as ugly and absurd.

In music, there was Bad Religion, Operation Ivy, Dead Kennedys… And I think that, in a way, some of that cathartic hardcore punk-rock feel was captured by the Grant/Breyfogle Detective Comics run.

I have news for you, the 2010s were far worse!

Anybody who thinks the 80s were bad, they must have some major issues.

Awwww yeah. I was wondering when you’d get around to The Good Grant.

In my opinion, his work is usually mighty entertaining, if lacking in reread value – and it took a pretty steady dive after Breyfogle left for greener pastures. Like most Brits, he was less interested in exploring/deepening Batman’s mythology than using it as a playground for his own ideas and interests (hence the proliferation of OC villains in his work; by some accounts Denny O’Neil had to twist his arm to get him to write anyone from the classic rogues), which might seem swell-headed, but next to the likes of (the Not So Good Grant) Morrison he’s downright humble. And while at his worst he went around grimdarking up Bat-books in ways Frank Miller could scarcely have dreamed, at his best I’d unironically say his Batman is the one I’d most like to share a soft-drink with. He’s just so honest, so earnest, so… so HUMAN. He flinches, he cries, he smiles… I think there might even be a time or two when he laughs out loud.

(Come to think of it – I don’t know if it’s a quirk of British Mags or whatever, but why does he always write dialogue like someone from Stan’s Bullpen? You don’t have to end every sentence in an exclamation point, dude.)

My favorite Grant story, I’d probably peg as the unabashedly sappy “Requiem for a Killer” (in all likelihood the first story that got anyone to give a shit about Killer Croc), but my favorite moment… that prize almost certainly goes to “No More Heroes”, when the teenage sniper pulls the trigger for the first time, then immediately vomits, too scared and too disgusted with himself to even look up and check if the bullet landed. That’s the kind of off-the-cuff rawness I’ve seen from few, if any other Bat-writers, no matter their skill.

I can’t agree about the lack of reread value, especially since I’ve read these comics soooo many times… Together with the various Batman Adventures series, the Alan Grant/Norm Breyfogle run would be my pick for desert island Batman books!

But it’s true that Grant belongs to the tradition of British writers who are generally less interested in building up on previous Batman stories (unlike their more fan-minded US counterparts) than in using the surreal atmosphere as a playground for unrelated ideas and interests. Peter Milligan, Garth Ennis, and Paul Cornell fall into this category as well (by contrast, Grant Morrison wrote one of the most insanely endogamous runs ever). Their amazing contributions actually ended up expanding and enriching the Dark Knight’s mythology. (When I find the time, I should also write something on the vast and bizarre version of the UK in Batman comics).

And yes, Alan Grant’s Batman is full of life and humanity, not least because Breyfogle’s art is so damn expressive. Bruce had a bit of the grimdark attitude, but he only really became a full-on dick after Grant left the Batman books (from No Man’s Land onwards). And don’t get me started on ‘No More Heroes,’ which is a masterclass in packing an issue with memorable moments, in terms of both action and characterization… There’s that scene you mentioned, with the teen sniper disgusted after shooting a street punk for the first time (ironically, while hiding at the top of a statue of Clint Eastwood, whose most famous roles glorified that type of deed). There’s also the Dynamic Duo relationship (in the early days of Tim Drake), the desperate gangsters, the frustrated owner of the theme park, the Yung Bluds vandals – each of these threads pays off in some way. Plus, at one point Robin fights a mechanical minotaur.

Thanks for the wonderful overview of the Grant/Breyfogle run.Along with Jim Starlin’s concurrent Batman run these issues are some of my all-time favorites.You should do an overview of Starlin’s run sometime.I think it would be great!Thanks for all the work you put into this site.Vince Wilson

Fantastic article bud. Grant is one of, if not my favourite writer in comics. His run was incredible and endlessly readable. Just wanted to let you know this was an absolute blast to read so thanks

Sorry but I have to disagree (or not really disagree since you pointed out his faults); Alan Grant was one of my least favorite Batman writers, and sort of emblematic of the miserable sludge doled out every month during Denny O’Neil’s 15-year editorial reign of terror. The problem with it was that Denny’s narrow view of Batman was the ONLY one allowed to be in the comics every month that it sort of became the permanent status quo, and Batman only kind of just started doing something a little different in the last few years.

Anyway, Grant seemed to be writer zero for the worst examples of this nonsense; your comment about the dead kids was spot on. What was the point of his diary stories like the Cataclysm back-up where the dude lets his son fall and break his head, then drops him again when he’s a paraplegic? There was no point other than to make the readers miserable. How this dude managed to hang on for 12 f-n’ years I have no idea, but I guess we have Denny and his favorites’ club to thank for that.

What more can I say… Denny O’Neil and Alan Grant are the main reason I fell in love with Batman comics in the first place. Their runs in the ‘70s and ‘80s have a way of bringing together a childlike sense of play and overblown pathos (which is sometimes so exaggerated that it becomes perversely amusing). I love it when franchises are able to succeed at different pitches while retaining some coherence. For instance, both Adventures of Zatoichi and Zatoichi’s Revenge are great entries into the Blind Swordsman series, even though the former is relatively family-friendly and the latter much grimmer, with more of a spaghetti western sort of vibe (and largely set at a brothel). Come to think of it, perhaps those movies actually had an influence on O’Neil and Grant!