Although he has fallen from grace somewhat in recent years, I think it’s not controversial to say that Alan Moore is a strong contender for the title of greatest comics’ writer of all time, and possibly God. Watchmen alone would secure his place in the medium’s pantheon, but Moore is hardly a one-trick pony, having created masterpieces in genres as diverse as political dystopia (V for Vendetta), superheroes/sci-fi (Miracleman), horror (Saga of the Swamp Thing), existentialist character study (A Small Killing), historical crime (From Hell), fantasy (Promethea), metafictional adventure (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen), and erotica (Lost Girls), as well as a mix of most of these in his phenomenal prose novel Voice of the Fire. He has also written a handful of comics involving Batman.

By putting intelligent twists on familiar archetypes and plots, Alan Moore’s genius lies in elevating conventional formulas into sophisticated entertainment (or, alternatively, in taking challenging concepts and making them accessible). Some of his comics can be demanding, but unlike his most pretentious peers Moore actually rewards you for the effort. For example, Watchmen is simultaneously a thought-provoking anti-superhero deconstruction AND an awesome superhero story, one that makes you care about a naked blue dude who sees through time and builds a palace on Mars.

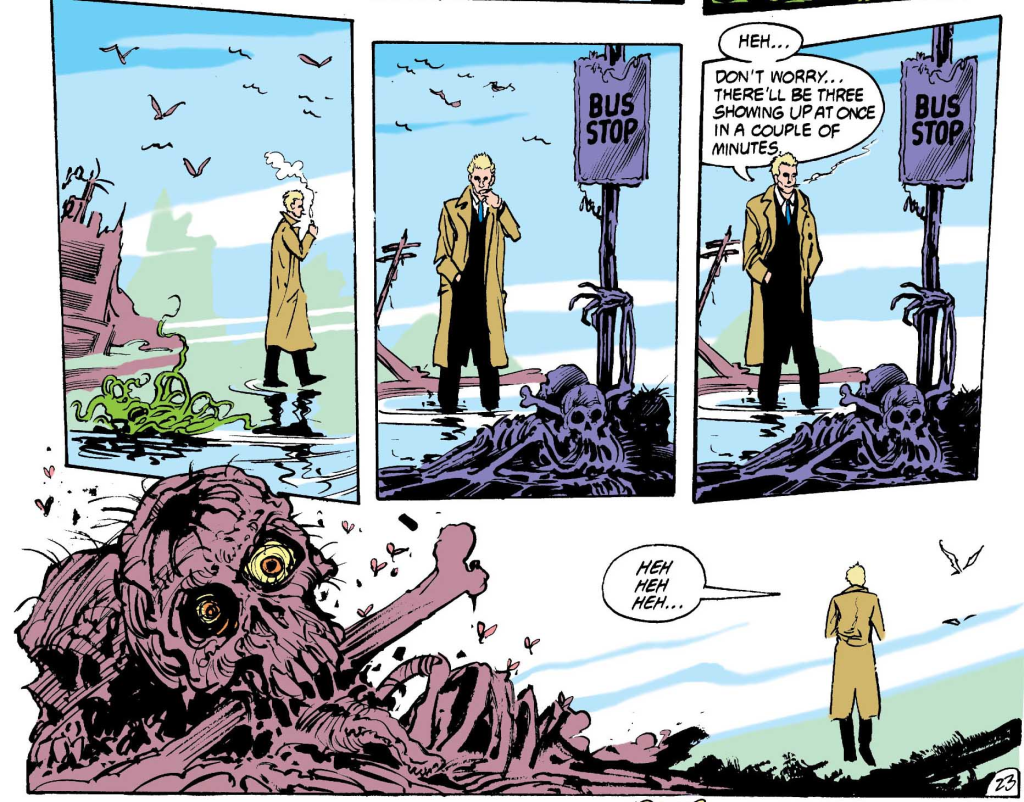

Moore’s most obvious trademark is to embed panels with various layers of juxtaposition, especially when transitioning from scene to scene. This technique can bring out themes by emphasizing symbolic connections, or it can merely amuse readers by creating visual puns. I say ‘merely,’ but I would argue that as a rule Moore’s playfulness is not appreciated enough except in discussions of his more blatantly comedic output (Future Shocks, D.R. & Quinch, Bojeffries Saga, Tomorrow Stories, Top Ten). I suspect the reason for this is that many fans prefer to think Alan Moore took his work as seriously as they do. However, even his grimmest stories are never devoid of a sense of humor, which (true to his British comics’ background) can be quite dark and iconoclastic.

Swamp Thing (v2) #39

Swamp Thing (v2) #39

There are three main themes in Alan Moore’s oeuvre. One of them is transcendence – many of Moore’s protagonists evolve beyond humanity not just physically, but through expanded consciousness, whether it be Michael Moran, Alec Holland, Jon Osterman, Sophie Bangs, or even Jack the Ripper. Moore gets a kick out of writing godlike POVs, resulting in some mind-bending reading experiences. Another recurrent theme, connected to this one, is the power of ideas. This is something he feels quite strongly about (as seen in the trippy documentary The Mindscape of Alan Moore) and it takes various forms in his books, which have addressed how reality can be transformed by ideologies, imagination, dreams, and, crucially, fiction.

The third, more controversial, leitmotif is sexuality. Alan Moore has taken a lot of grief from critics and colleagues for the abundance of rape in his comics. Although this is a valid object of analysis, I think it kind of misses the larger point: Moore’s comics (and prose, and short films) are not fixated on rape as much as they are fixated on sex, in all its forms. Across his work, there is gay sex and straight sex, threesomes and orgies, role playing and bondage, incest and necrophilia, sex with transgender characters and minors and animals and superheroes and aliens and gods and Earth elementals. There is sexual violence, for sure, in some instances treated in a realistic, respectful way or as a powerful satirical metaphor, and other times played for laughs or gratuitous shock value. But there is also plenty of loving, tender sex and joyful lust. Not only has Moore written a whole art/porno graphic novel concerning the lesbian exploits of Alice (from Alice in Wonderland), Wendy (from Peter Pan), and Dorothy (from The Wizard of Oz), thanks to him one of the biggest mainstream publishers in the field has released some highly original comics devoted to sex:

Overall, Alan Moore’s Batman stories are not all that rich as far as these themes go, which may be an indication of how relatively little he invested in them. In that sense, Moore’s work with Superman is much more fascinating (not only the actual Superman tales, but also the stuff with Supreme and Mr. Majestic). Needless to say, this will not stop me from picking those comics apart.

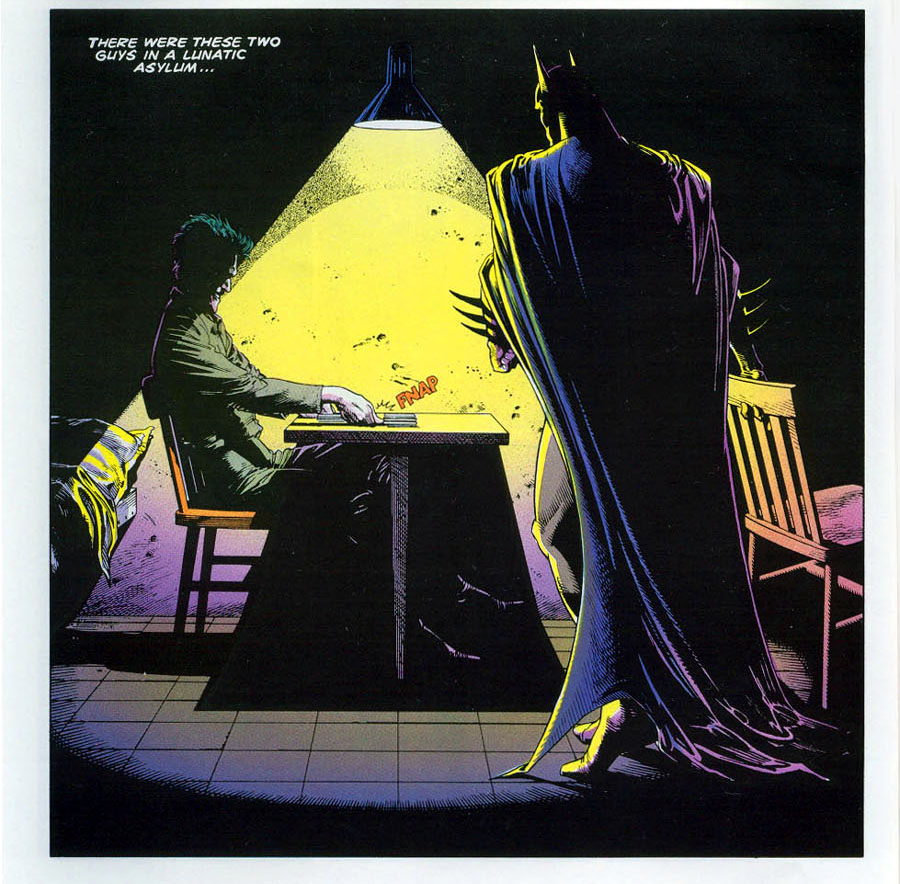

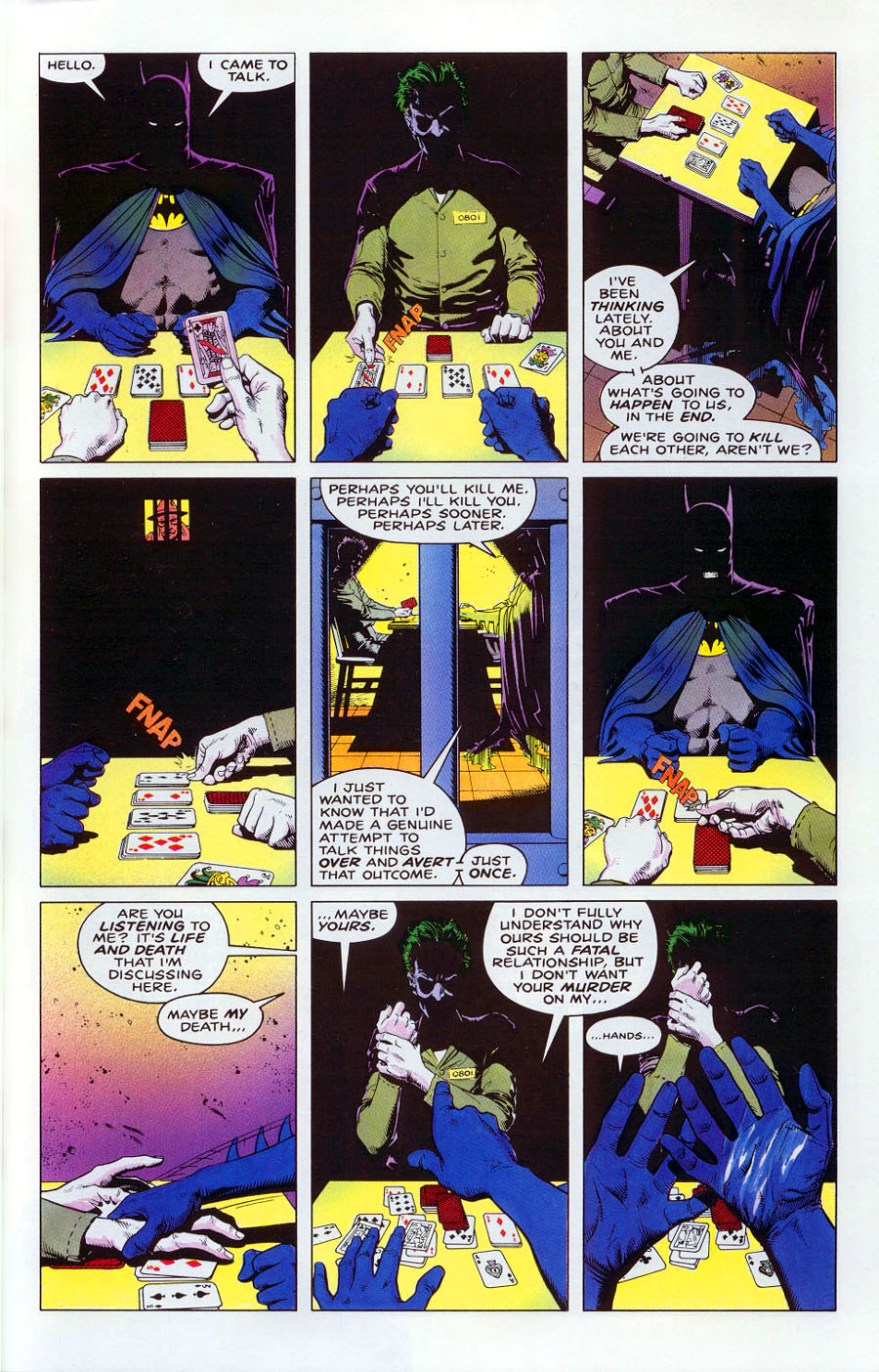

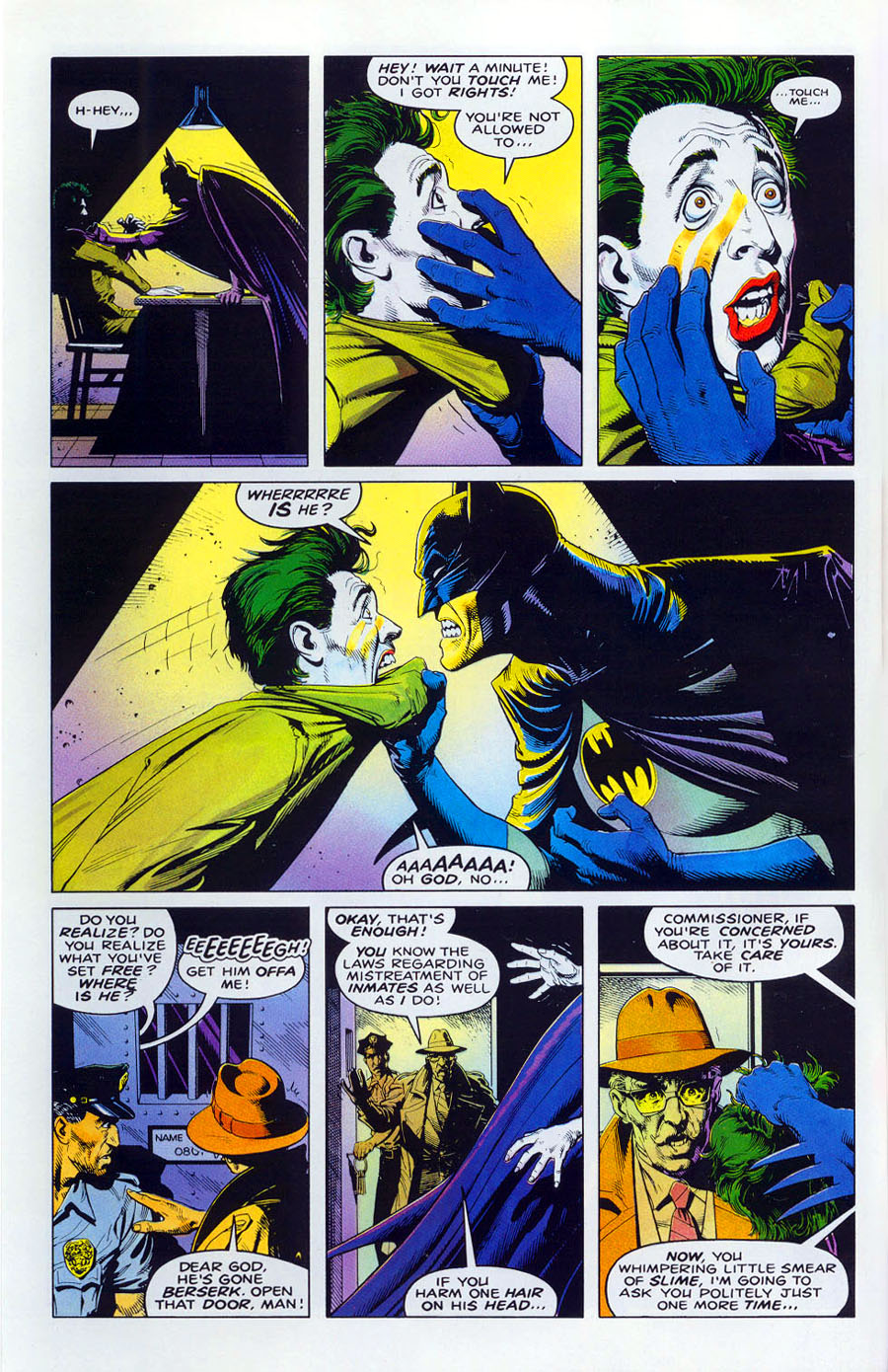

Moore’s best known Batman work is The Killing Joke. It has been analyzed to death, from the role of dualism to its homoerotic subtext. Although Brian Bolland’s gorgeous pencils are a great part of the book’s appeal, the script itself has gained legendary status, especially Moore’s opening words for Bolland:

WELL, I’VE CHECKED THE LANDING GEAR, FASTENED MY SEATBELT, SWALLOWED MY CIGAR IN A SINGLE GULP AND GROUND MY SCOTCH AND SODA OUT IN THE ASTRAY PROVIDED, SO I SUPPOSE WE’RE ALL SET FOR TAKE OFF. BEFORE WE GO SCREECHING OFF INTO THOSE ANGRY CREATIVE SKIES FROM WHICH WE MAY BOTH WELL RETURN AS BLACKENED CINDERS, I SUPPOSE A FEW PRELIMINARY NOTES ARE IN ORDER, SO SIT BACK WHILE I RUN THROUGH THEM WITH ACCOMPANYING HAND MOVEMENTS FROM OUT CHARMING STEWARDESS IN THE CENTRE AISLE.

[…] I WANT YOU TO FEEL AS COMFORTABLE AND UNRESTRICTED AS POSSIBLE DURING THE SEVERAL MONTHS OF YOUR BITTERLY BRIEF MORTAL LIFESPAN THAT YOU’LL SPEND WORKING ON THIS JOB, SO JUST LAY BACK AND MELLOW OUT. TAKE YOUR SHOES AND SOCKS OFF. FIDDLE AROUND INBETWEEN YOUR TOES. NOBODY CARES.

Like John Ford’s The Searchers, this work keeps making it to ‘best of’ lists mostly on the strength of people’s memories of an impressive beginning and a killer ending, disregarding the flaws in the middle (although at least The Killing Joke never meanders, as each panel ties perfectly into the next). Which is not to say that there hasn’t been a backlash. According to your mindset while reading it, The Killing Joke can be either a fantastic Joker story (one with a defining take on the Clown Prince of Crime, with one of his most extreme plans, and with an interesting examination of his relationship with the Dark Knight), or a terrible Batman comic (one where Batman doesn’t do much until the end, where cruel things happen to beloved characters, and where there isn’t any fun to be had).

As for the Moore elements highlighted above, the book is full of symbolic and/or darkly humorous juxtapositions. Just check out the following scene:

Transcendence doesn’t play much of a role in the book, except perhaps in the sense that Batman and the Joker seem to metafictionally realize they are stuck in a loop, unable to break character. The story does touch upon the power of ideas (more specifically, madness) and sexuality (Barbara Gordon’s naked pictures), but not in a very profound way…

Transcendence doesn’t play much of a role in the book, except perhaps in the sense that Batman and the Joker seem to metafictionally realize they are stuck in a loop, unable to break character. The story does touch upon the power of ideas (more specifically, madness) and sexuality (Barbara Gordon’s naked pictures), but not in a very profound way…

Ultimately, I would say that The Killing Joke doesn’t deserve a place near the top of Moore’s cannon (or, arguably, Batman’s cannon) but it is hardly a complete failure. After all, even when not blowing your mind an average Moore book can still hold its own. The Ballad of Halo Jones and Tom Strong are more satisfying than 90% of the comics that came out last week. Hell, even Moore’s stints in Spawn and WildC.A.T.S. are quite enjoyable in their own right. Sure, there are exceptions, but not that many!

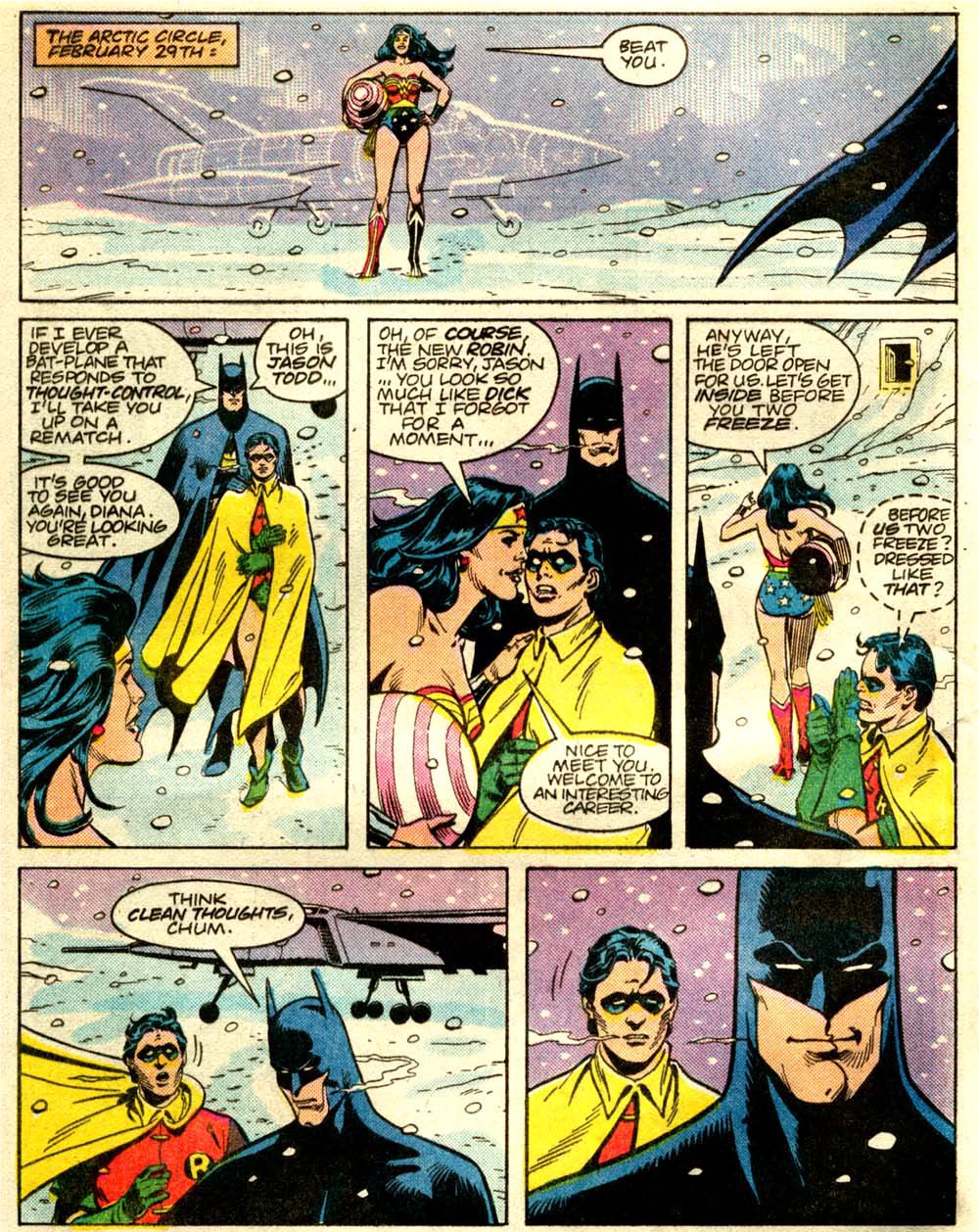

The other prominent Alan Moore comic to feature the Caped Crusader is the classic Superman tale ‘For the Man Who Has Everything.’ Once again, Batman isn’t given much to do in the story (as opposed to Robin, who totally saves the day!). He does, however, get a line that is both funny and naughty:

Superman Annual #11

Superman Annual #11

In contrast to these well-remembered tales, Alan Moore’s most obscure piece of Batman writing is probably ‘The Gun,’ a prose short story (with a few illustrations by Garry Leach) for the British Batman Annual in 1985. Much like Winchester ’73 (a way cooler western than The Searchers), the story follows a gun as it’s passed from owner to owner, including Joe Chill, who uses it to murder Bruce Wayne’s parents. Although oozing with a 1980s’ urban grit vibe, Moore uses the setting of the Gotham City Fair to hint at the kind of surreal constructions you could find in the old comics:

‘To his left stood a gigantic Thermos flask, fully seventy feet tall.

To his right stood a massive chromium washing machine the size of a house. Everything was bright and colossal and gleaming, with brilliant coloured spotlights playing over the exhibits and the thronging crowds. Happy families moved in streams around the exhibits like shoals of neon-lit tropical fish swimming in an ocean of piped Muzak.’

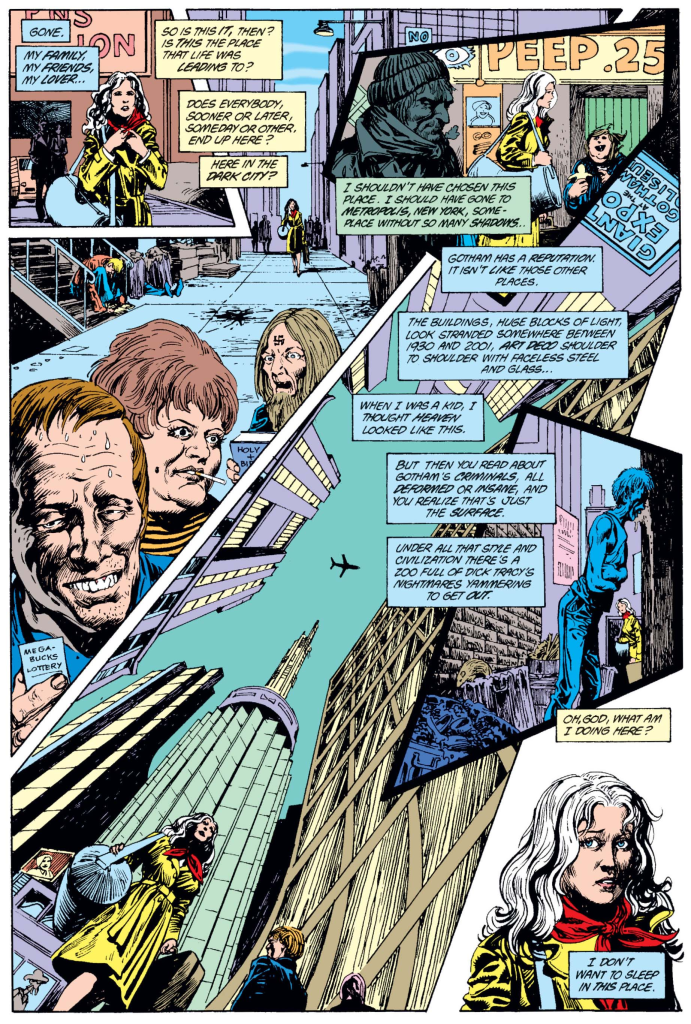

Alan Moore’s most engrossing take on the Batman universe, however, took place in the pages of Swamp Thing, the beloved horror series about a muck creature who learns how to channel the vegetable kingdom. The Caped Crusader has a brief cameo in issue #44, but #51 really takes things to another level. Here, Swamp Thing’s girlfriend, Abigail Cable, finds herself in a bizarre court case over the fact that she had sex with the plant monster (technically, she is charged with ‘crimes against nature’). Unable to deal with moral intolerance in Louisiana, she jumps bail and runs away to Gotham City, a ‘place where people can get lost.’ When she arrives, Moore applies to Gotham the series’ characteristic purple prose, accompanied by Rick Veitch’s haunting illustrations:

Swamp Thing (v2) #51

Swamp Thing (v2) #51

The sexual motif, already present in the story’s premise, reappears as Abigail immediately meets some friendly prostitutes and gets arrested by a police raid. Realizing she is a fugitive, Gotham law assigns her an extradition hearing. Meanwhile, public opinion goes berserk over the so-called Louisiana ‘Beauty and the Beast’ morals scandal.

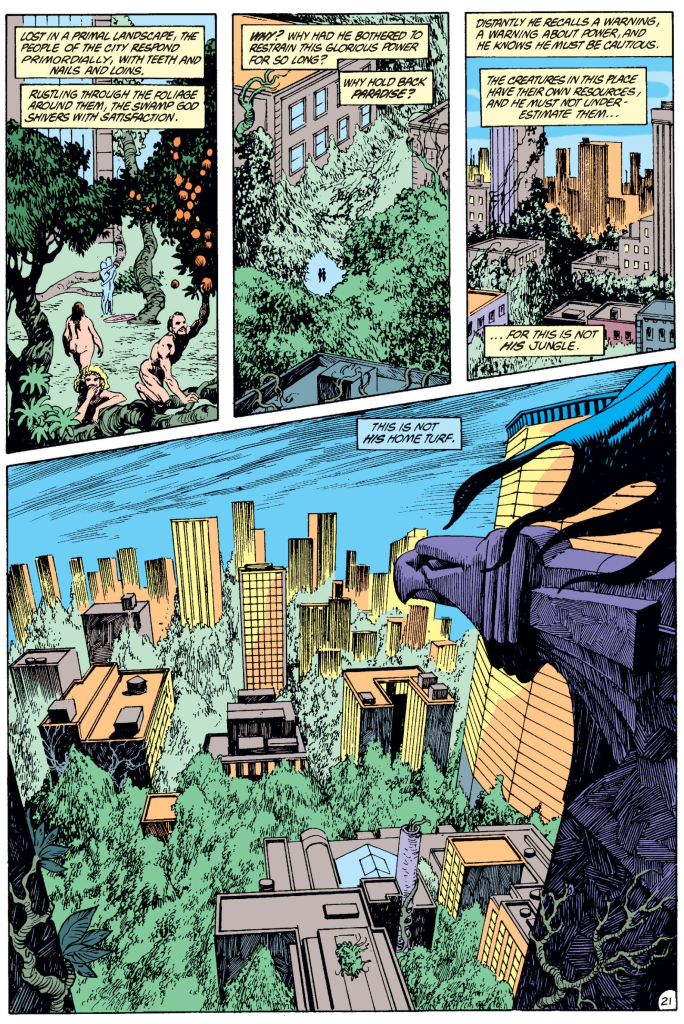

In issue #52, Swamp Thing comes to Abby’s rescue, giving the city authorities an ultimatum: either release her in the next hour or deal with an enraged vegetable demigod. Nothing happens, so Swamp Thing responds by using his green powers to turn Gotham into a jungle, which leads to some breathtaking sequences:

Swamp Thing (v2) #52

Swamp Thing (v2) #52

Gotham being Gotham, citizens deal with this transformation in the most outlandish ways, quickly adapting to the new surroundings by unleashing their buried urges. The whole thing turns into a weird social experiment…

And then the Dark Knight comes onto the scene, spoiling everyone’s fun by crushing the foliage with his metallic Batmobile and attacking Swamp Thing with defoliant. In Moore’s world, if Swamp Thing is the liberator of humankind’s natural instincts and the avenger of ecological crimes, then Batman is the defender of the industrial and puritanical status quo. Appropriately enough, the Caped Crusader gets his ass handed to him by the supernatural monster. When he ultimately wins (he’s Batman, after all), it’s not by defeating Swamp Thing, but by standing up to Gotham’s mayor and arguing for sexual tolerance:

Swamp Thing (v2) #53

Swamp Thing (v2) #53

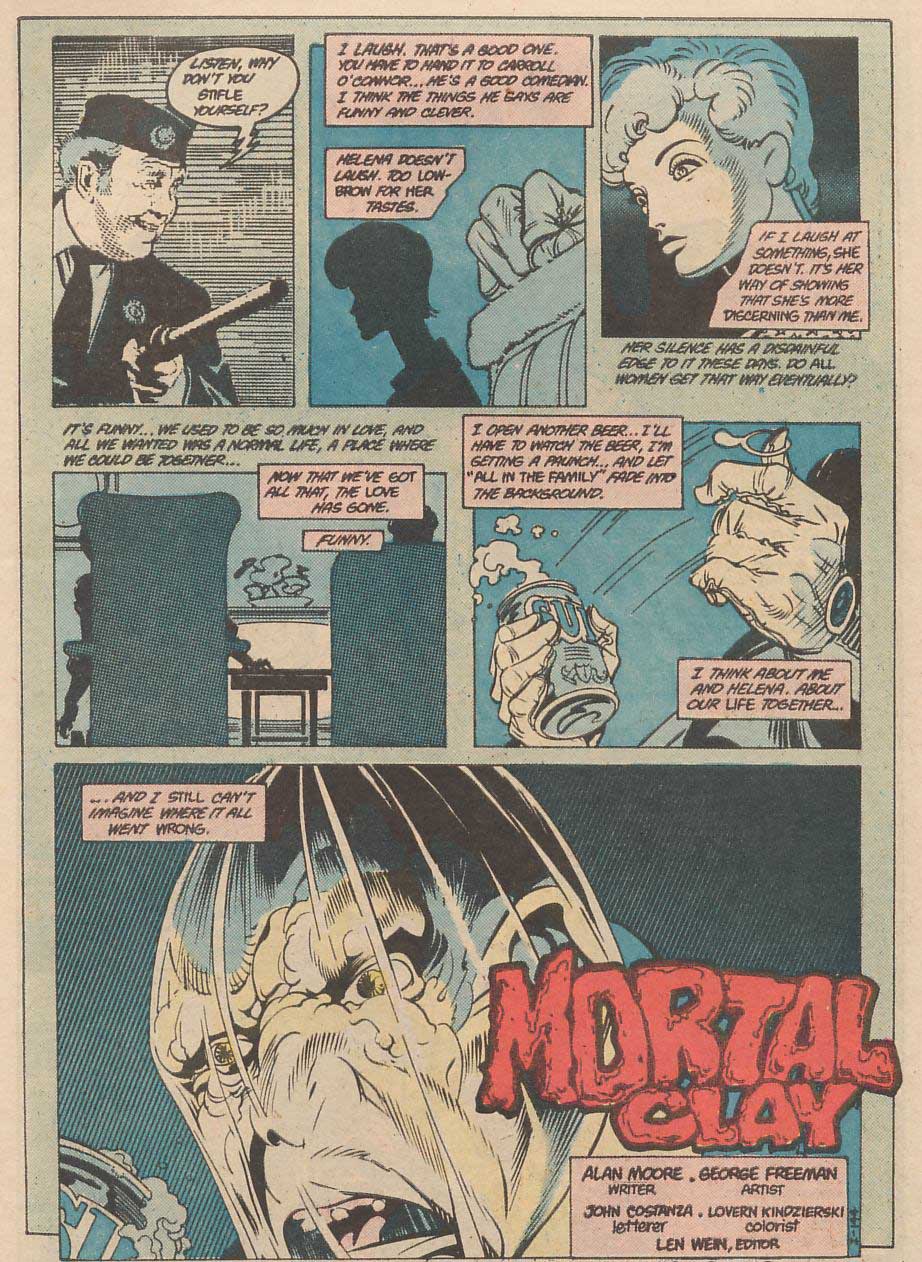

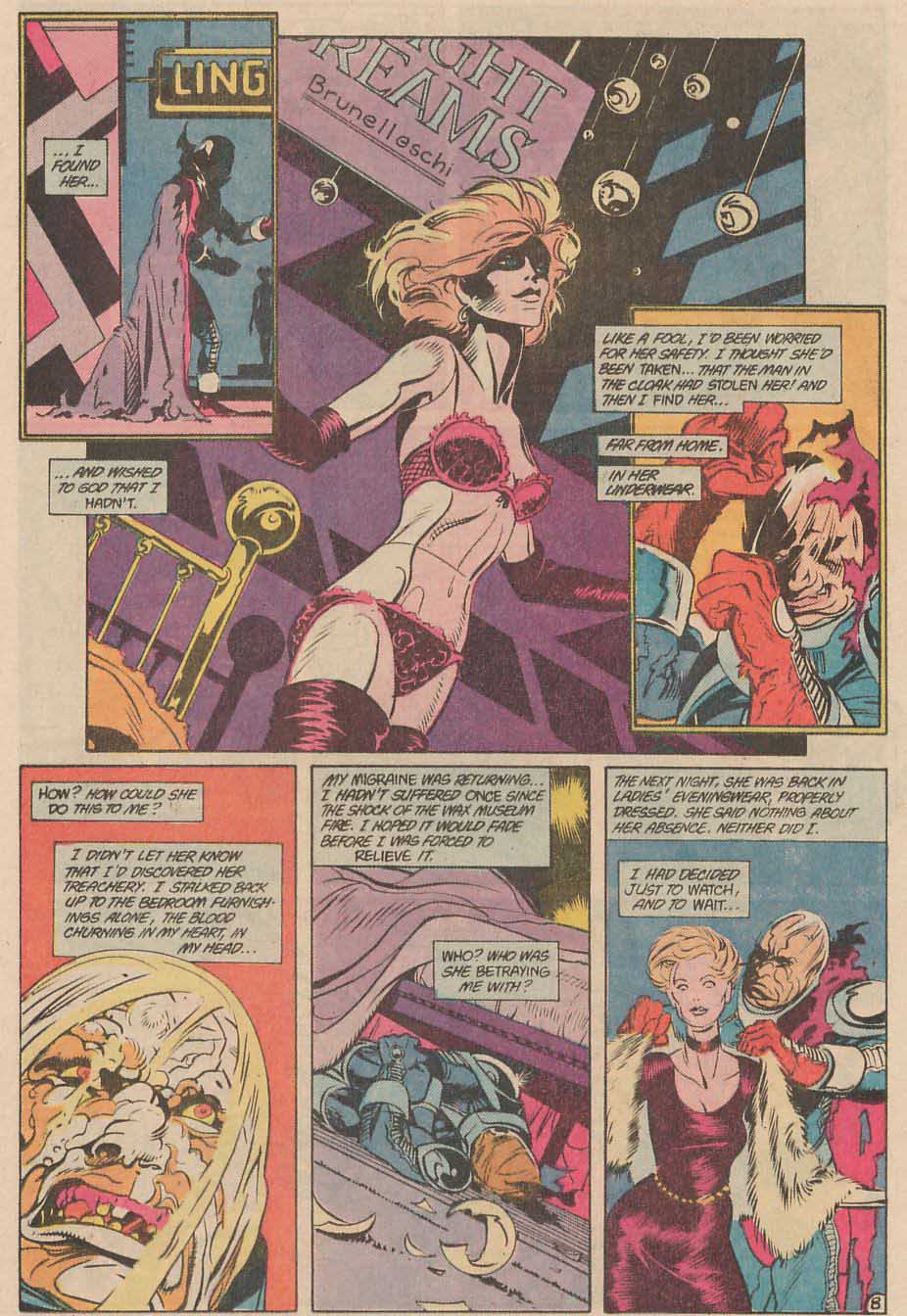

We get yet another unconventional affair in Batman Annual #11. ‘Mortal Clay’ is a sequel to Len Wein’s and Marshall Rogers’ Detective Comics #478-479, which introduced Preston Payne (aka Clayface III), a toxic, deformed man in an exoskeleton suit who believes he is in a relationship with a store mannequin called Helena:

Part of the joke is that because of Preston Payne’s old fashioned values he can hardly distinguish between an actual woman and a lifeless, female-shaped dummy. But there is also a kinky undertone, especially as Payne starts to suspect that Helena is cuckolding him with Batman. Of course mannequins are designed to be sexualized to some degree (two store clerks even discuss their arousal), so in a sense Payne is only responding to the wider objectification of women, in his own twisted way:

Part of the joke is that because of Preston Payne’s old fashioned values he can hardly distinguish between an actual woman and a lifeless, female-shaped dummy. But there is also a kinky undertone, especially as Payne starts to suspect that Helena is cuckolding him with Batman. Of course mannequins are designed to be sexualized to some degree (two store clerks even discuss their arousal), so in a sense Payne is only responding to the wider objectification of women, in his own twisted way:

Moore gets a lot of mileage out of juxtaposing Payne’s delusional narration with the reality on display in the images. It’s a fun story that ends with a suitably dark punchline.

Moore gets a lot of mileage out of juxtaposing Payne’s delusional narration with the reality on display in the images. It’s a fun story that ends with a suitably dark punchline.

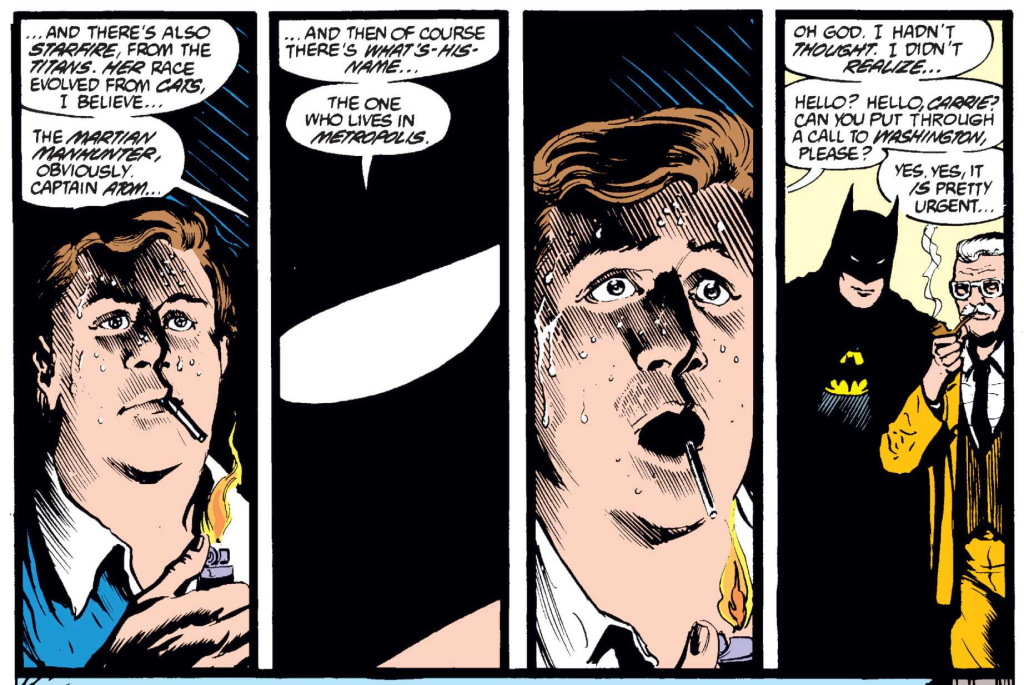

This is pretty much all we got in terms of straightforward Batman stories. Alan Moore’s take on the Dark Knight never reaches for transcendence. His Batman isn’t the World’s Greatest Detective, just a run-of-the-mill hero. In fact, he isn’t even a mysterious creature of the night, since he gives a public speech at Swamp Thing’s funeral (Swamp Thing #55). Perhaps Moore’s unpublished project, Twilight of the Superheroes, would have changed this: in the proposal, Batman, The Shadow, Tarzan, and Doc Savage were described as being ‘basically more elemental forces than people.’

In a less literal sense – and I know I’m not the only one to spot this – Batman is all over Watchmen. Rorschach is an extreme version of the gritty vigilante you can often find in Detective Comics. Ozymandias (who was born in 1939, the year of Batman’s debut) is a rich genius, one who transcends common morality and changes the world by using artists and inventors. Night Owl has the toys, as well as a sexual fetish related to the dangerous lifestyle and ridiculous costume. I could now go on to write another 20,000 words about Watchmen, but more erudite minds than mine have already done it (for example, the always knowledgeable Tim Callahan).

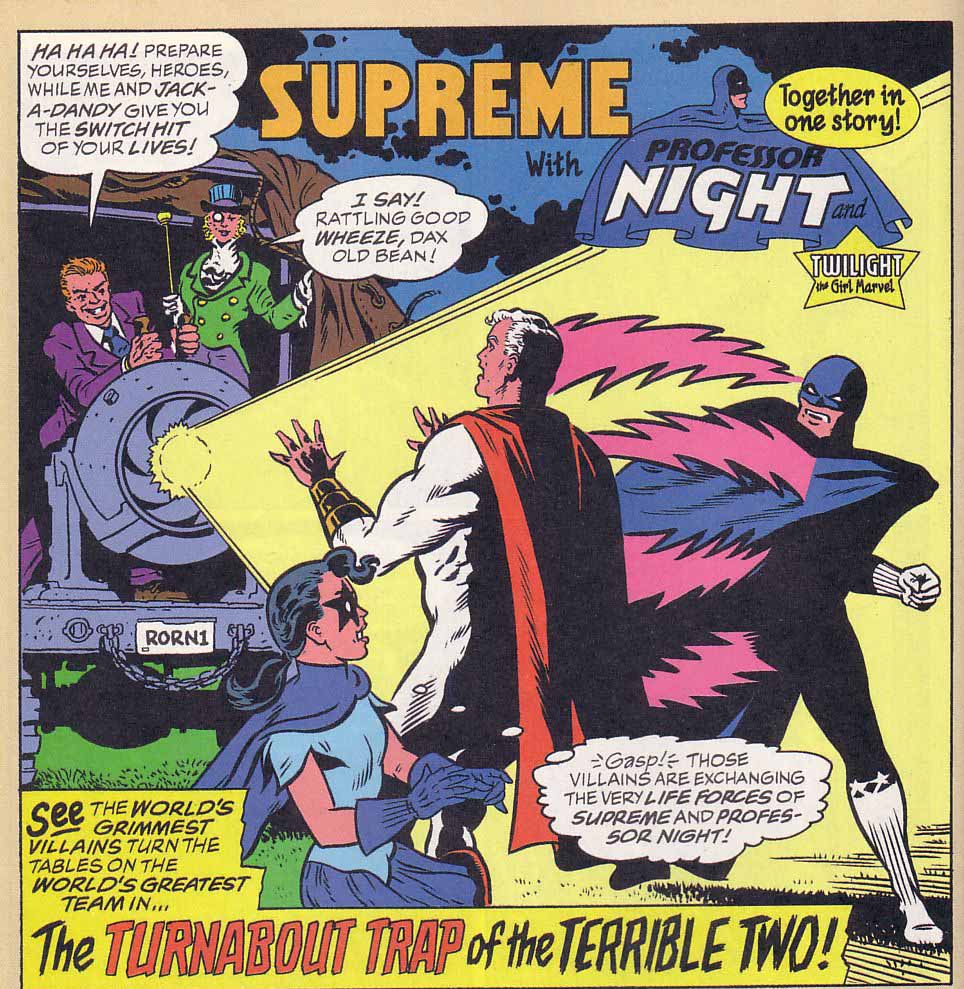

In any case, as far as Batman analogues go, nothing beats Professor Night in Alan Moore’s pastiche of 1950s’ World’s Finest Comics…

Supreme #47

Supreme #47

Seriously, this version of the Batcave even has an ‘ultra-modern computer that can deliver dozens of facts within minutes.’ Adorable.

NEXT: Crocodiles.

Well, the deep context in The Killing Joke that somehow everyone keeps forgetting while discussing it despite being blatantly spelled out in the pages lies in Joker’s ruminations on the lack of meaning of life, which I find puzzling to see are ignored so often, despite being one of the of the greatest conundrums that have plagued mankind forever, and which we try to mitigate by convincing ourselves of things that make us sure there are planes of existence beyond this one, invisible rules that give the world a sense that is above ourselves as individuals…

Maybe it’s something people doesn’t want to think about too much, so it often goes overlooked in these discussions? Even by Moore himself?

That’s true. I’ve seen many critics (and Moore himself) dismiss The Killing Joke as just a story about Batman and the Joker, nothing more. But of course there is that broader theme of different ways to cope with a meaningless, unfair, cruel world: the Joker responds by turning into a sadistic clown, Bruce Wayne tries to force order trough vigilantism, Gordon insists that justice be achieved ‘by the book’.

Also, and I should have pointed this out, the Joker sings a twisted song, which is something that happens a lot in Moore’s comics… I keep waiting for some musical project to bring to life all his lyrics from Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Bojeffries Saga, Future Shocks, Top Ten, Promethea, Tomorrow Stories, and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.