As I’ve pointed out before, this year has brought to life elements from various works of science fiction. However, the appeal of sci-fi is not always realistic accuracy… there is also plenty of fun to be had with counter-intuitive imagination. To quote Adam Roberts, at its most enjoyable this is a fundamentally metaphorical genre that ‘is more like a poetic image than it is a scientific proposition.’ Indeed, some science fiction can even be best appreciated as a mostly aesthetic experience (for example, Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain would be boring as hell if it wasn’t for its staggering set design…).

With that in mind, today I want to celebrate, not those comic books that more or less predicted what we’re going through, but those whose vision of the future remains as strange today as when they first came out… or even stranger! Some may still turn out to be prescient, others certainly won’t, but here are a few fascinating comics that, for the most part, do not reflect 2020:

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

As if it wasn’t bizarre enough assigning Jack Kirby to do a comic book adaptation of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (in 1976, almost a decade after the film came out…), Marvel then followed the project with an ongoing series that lasted for ten glorious issues. The adaptation one-shot is as baffling as you’d expect, given the blatant contrast between the film’s meditative script (by Kubrick and sci-fi luminary Arthur C. Clarke) or its elegant, understated visual style and Kirby’s crude, bombastic, wordy brand of storytelling (admittedly an acquired taste) – the result feels like a distorted memory of the original with an exhausting voice-over explaining everything you might have missed. But although that book’s appeal is mostly as a curious artifact for Kirby scholars, the ensuing ongoing series can be genuinely stimulating for fans of surrealist science fiction.

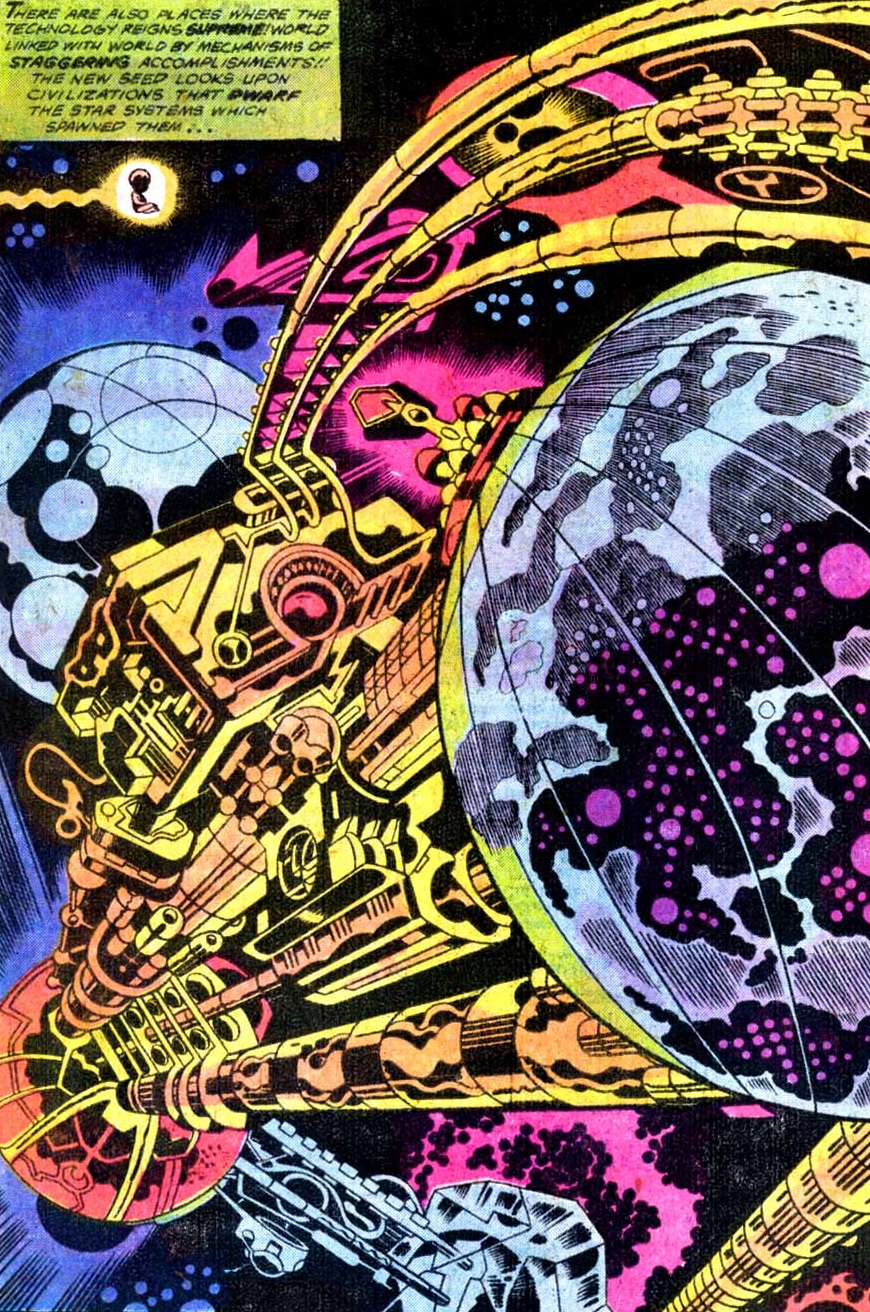

Probably Kirby’s densest work in terms of both themes and abundant, intricate prose, 2001: A Space Odyssey is a kind of mind-bending anthology, following different characters throughout the ages who come into contact with the film’s alien Monoliths, spurring human evolution (usually in the form of technological progress and organized violence). Despite the references to evolution, though, Kirby’s take on history isn’t as linear as all that, since he uses the series’ gradually looser formula as a springboard to visualize diverse types of future, including not only ultra-technological space exploration, but also polluted, hyper-commodified cities and post-apocalyptic wastelands. The result is a challenging read at first, but also a delight to stare at, with its stark designs (pleasingly inked by Mike Royer) and psychedelically-colored double-page spreads that seem to jump out of the paper, all the while repurposing plenty of imagery from the movie (from the pre-historical settings to the creepy baby), with most stories featuring variations of Kubrick’s famous millennia-long flashforward/match-cut.

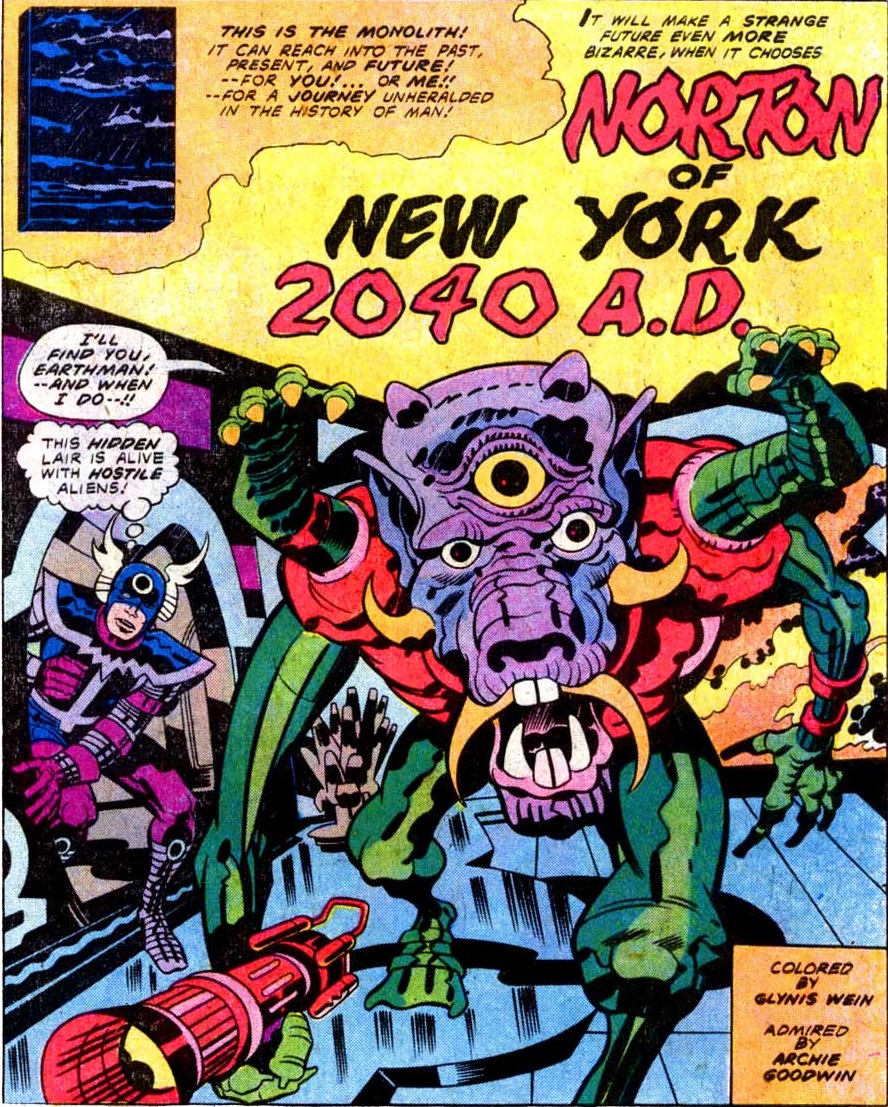

The actual year 2001 looked nothing like this. Yet, as the series moves forward in time, there are some insightful glimpses of plausible things to come, at least once you get past all the gonzo gadgets. The brilliant issues #5-6 are set in 2040, when ‘comics have reached their ultimate stage,’ as ‘what began with magazines, fanzines, and nation-wide conventions has culminated in a fantastic involvement with the personal life of the average man!’ It’s hard not to see in this tale hints of today’s toxic fandom, as it posits a world in which ‘the descendants of the early readers’ have molded their emotional lives around superhero fiction, dealing with the social alienation of an impersonal urban landscape by paying to experience elaborate simulations of their fantasies. One of the most personal – and certainly the most meta – stories in the whole run, this arc hilariously kicks off with Kirby parodying his own writing and drawing style, mocking the very genre he helped flesh out:

As the series kept experimenting with format, the final issues did turn into a kind of superhero comic, with the introduction of the sentient android Machine Man, who soon spun off into his own series and eventually became a regular player in the Marvel Universe (with particularly memorable roles in Nextwave: Agents of H.A.T.E. and Marvel Zombies 3). That’s right, the Marvel Universe is somehow connected to the continuity of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, just as it is connected to H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. I love this stuff.

Looking at the 2001 comics today, they do feel futuristic, if not in form or content, at least in spirit. To borrow their own terminology, this series was like the next evolutionary leap from Jack Kirby’s metaphysical sagas in Thor and The Fourth World, whose relentless energy and explosion of wild ideas – constantly coming up with outlandish mutations and cosmic pantheons – have proved highly influential in the medium. You can still see 21st century comics trying to tap into that expressionistic, cumulative over-the-top feel of massive battles with creatures of all shapes and sizes, like in Gødland, Vimanarama, and God Is Dead – although in the latter case, because it was published by Avatar Press, with lots more sex, profanity, and gore.

Speaking of which…

2020 VISIONS

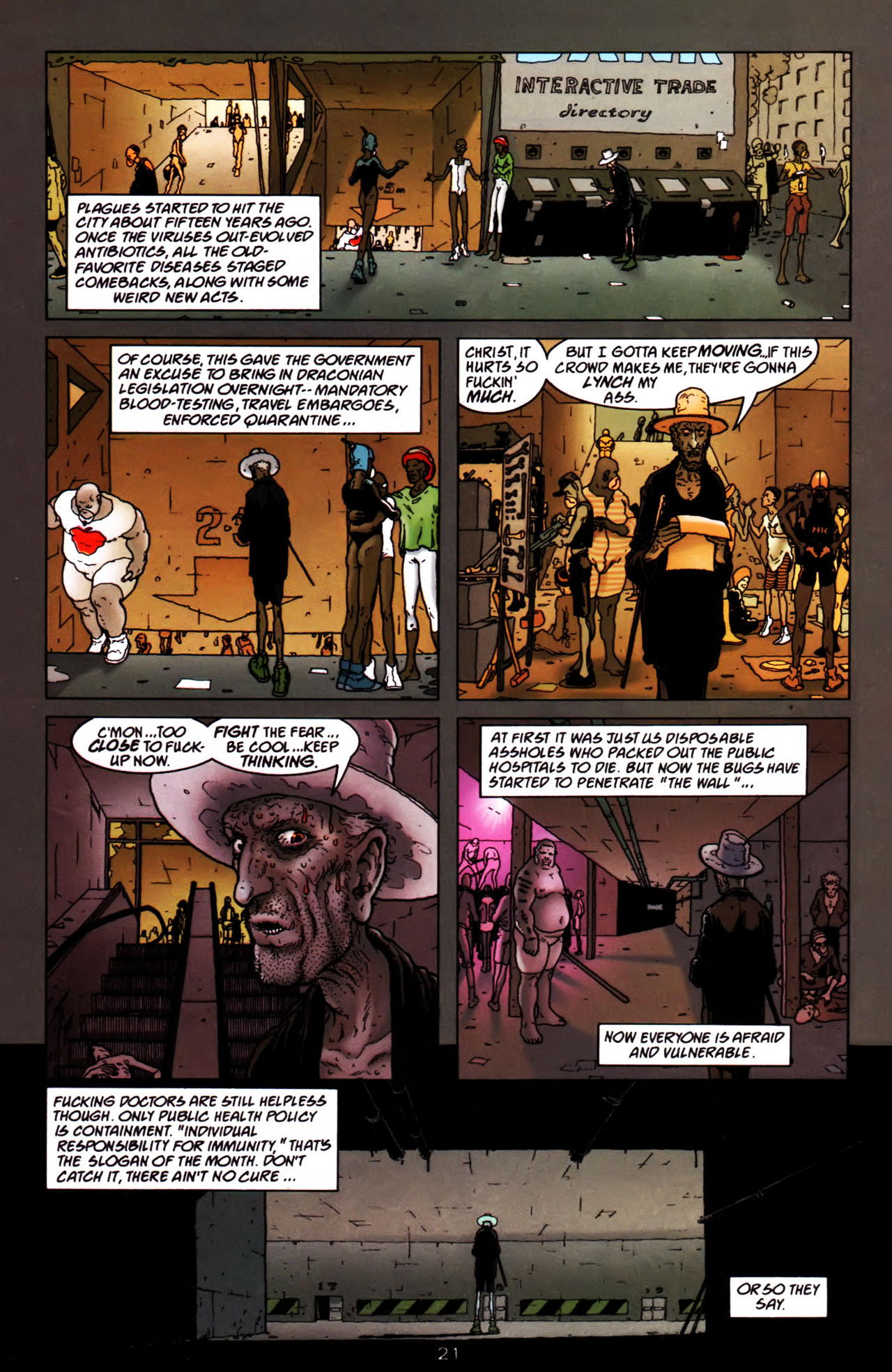

Based on the page above, you’d be forgiven for thinking that 2020 Visions, originally serialized in 1997, hit more than it missed in its envisioning of 2020. You’d be incorrect: the virus plaguing this comic’s future America is actually a bug that ramps up people’s sexual drive, getting them uncontrollably horny for people and objects (‘screwin’ an’ grindin’ till they bleed right through their skin’), and power is actually in the hands of an ‘intellectual-feminist Presidential dynasty’ after the ‘New Right tax- and vote-strikes destroyed traditional two-party politics.’ With multiple artists and multiple palettes by James Sinclair (ranging from toxic neons to sun-drenched desert colors) yet held together by Jamie Delano’s typically depraved gutter punk prose, 2020 Visions presents another idiosyncratic dystopia.

Granted, a lot of what then passed for anarchic, provocative satire now reads somewhat like an alt-right-conceived nightmare, with its jabs at a ‘P.C.-moralist Administration’ that outlawed pornography and expelled a whole underclass of citizens who didn’t fit into ‘the global electronic economy.’ The hardcore levels of nasty sex, violence, and swearing seem designed to elicit all the major trigger warnings. Plus, there are offensive (if obviously tongue-in-cheek) cultural stereotypes in the depictions of the near-feudal Catholic state of Nueva Florida (which came about when a cartel of second-generation immigrant families led a secession from the Union and annexed Cuba) and of Free Islamic Detroit (‘a pretty good place to live – as long as you’re Black, Muslim, and content to be ruled by harsh Sharia law’). To be fair, this is one of those works where nobody is spared: the vision of the Bible Belt is just as grim, with segregated societies ‘functioning under cultures of armed self-reliance, defined by Xenophobia and religious fanaticism, and governed by warlords and resource barons.’ Above all, one of the driving forces seems to be a cynicism towards self-entitled, oppressive identity politics, as our initial point-of-view character rants that he saw ‘a feeding frenzy of tyrannical minorities tear the nation apart’ (from creationists and evolutionists to ‘all kindsa fuckin’ fundamentalists’).

Regardless, if you stick with it, willing to laugh at all the sleazy, caustic exaggeration, you’re bound to find in 2020 Visions a cleverer, richer comic than what a first impression might suggest…

As the opening issue’s back matter indicates, Jamie Delano is less interested in speculative futurology than in finding interesting human drama in original places, as reflected by the overall structure: a 12-issue series broken into four arcs with different protagonists and tones.

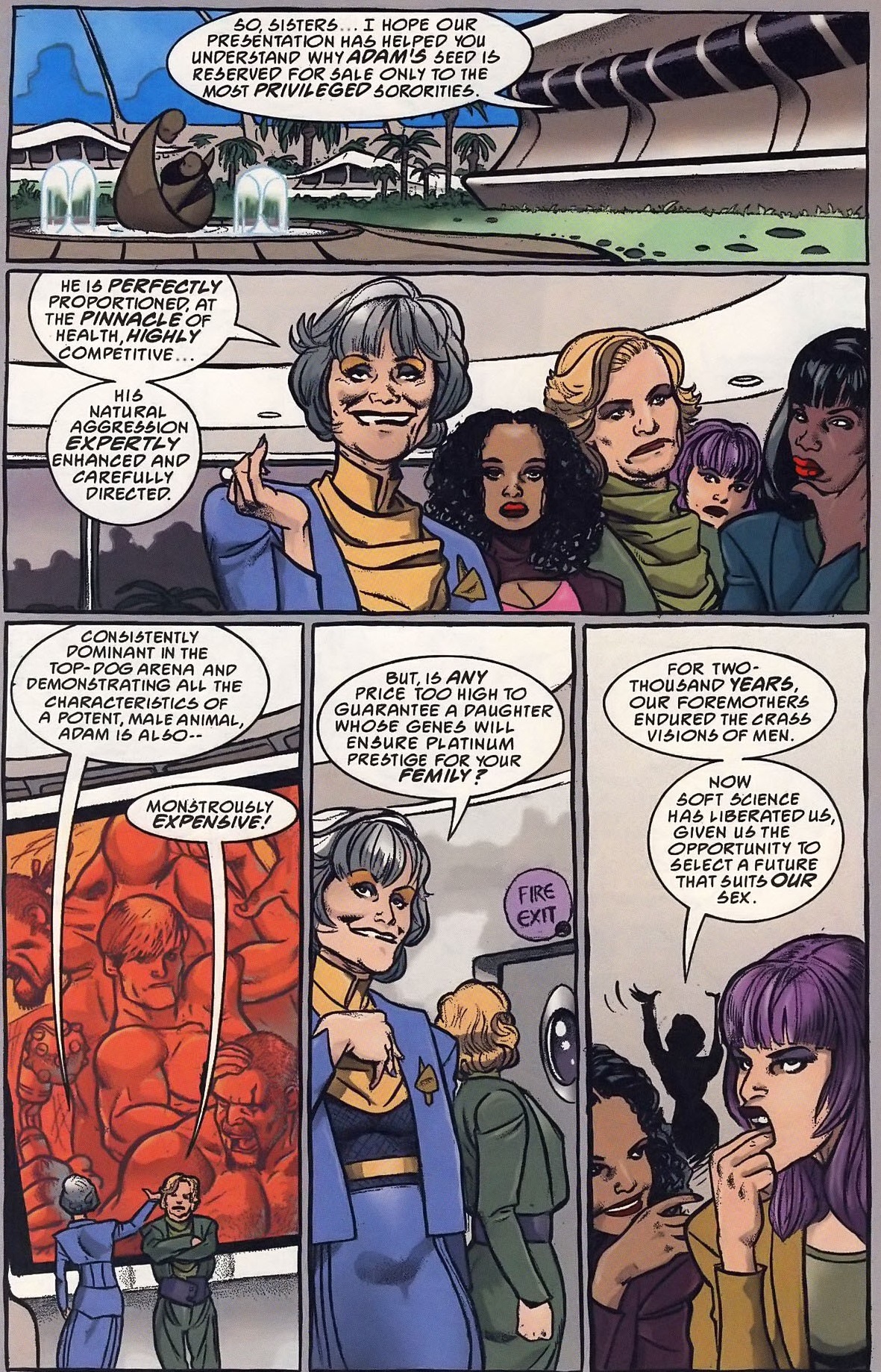

Thus, the decadent porn dealer who leads the first story (with vibrant Frank Quitely art) is hardly the only guiding voice throughout the comic – and, indeed, it’s immediately clear that he’s meant to be a selfish bastard (or, as another character puts it, ‘a crab-louse in the stinkin’ crotch of a necrophiliac mortician fucking the decaying corpse of friendship, trust, and human decency’). In turn, the second arc, a noir mystery set in a semi-flooded (due to global warming) Miami, revolves around a traumatized crossdressing detective, which poignantly clashes with the surrounding Latin machismo (artwise, Warren Pleece’s designs, like those of James Romberger in the next arc, are too stiff for my taste… but they help sell the idea that this is a world of very diverse environments). The series finishes with a brutal neo-western in the ‘militia country’ of the New Montana Territory of Freemen and a quasi-romantic thriller (drawn with a lighter touch by Steve Pugh) that kicks off in a technologically secluded, female-dominated LA where men are hyper-objectified by Hollywood and sexual reproduction is illegal, with babies being bio-engineered by repro-corporations.

ELMER

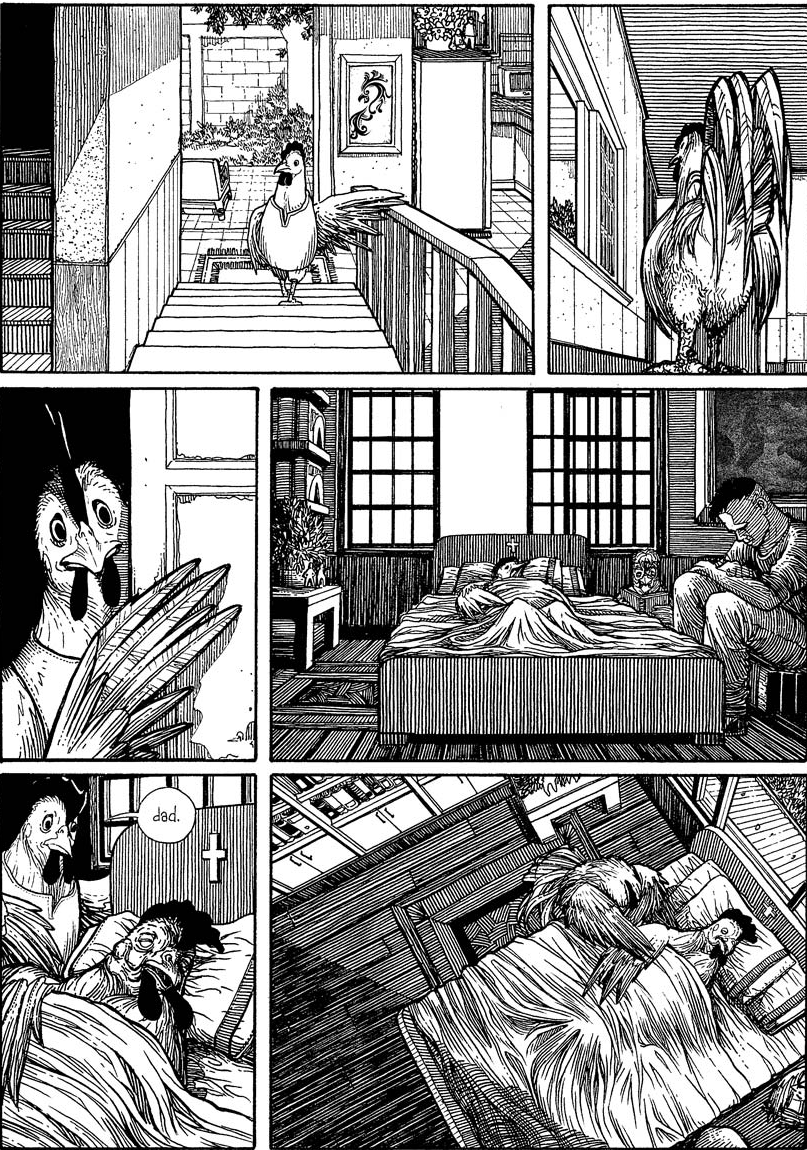

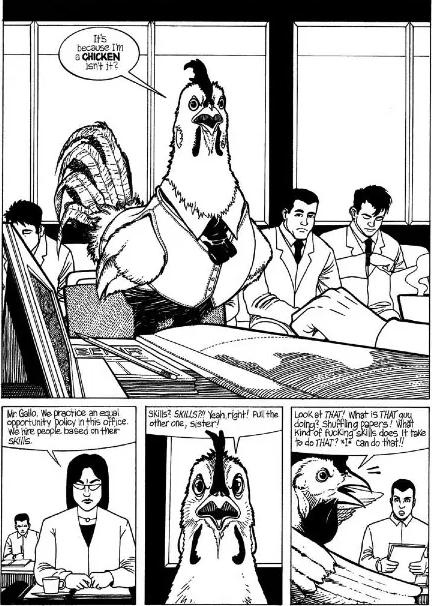

By contrast, here we have a masterful sample of subdued speculative fiction. Gerry Alanguilan’s 2006 comic imagines what could happen if chickens gained consciousness and the ability to speak… and sought to integrate the human race. It may sound like a ridiculous premise, but it’s played eerily straight, as we follow the journey of Elmer, one of the first chickens to awake, and his son, still trying to adjust to the world a generation later.

The best part is that Alanguilan doesn’t try to force a metaphor. Sure, you can find in the tale glimpses of slavery, apartheid, and the holocaust, not to mention a vegetarian parable… and you can project parallels with the civil rights struggles of every marginalized group. However, Elmer focuses on the specific case of chickens and lets the themes (discrimination, retribution, reconciliation, traumatic memory) emerge naturally from the story.

Although much of the appeal comes from the world-building, Gerry Alanguilan wisely keeps it as a backdrop that you gradually fill in, anchoring the book on Elmer’s touching family drama. The writing is sharp (‘I’ve been a human longer than you have, Elmer. I know these people.’), but what really sells it is the realistic draughtsmanship, with the artwork pulling off moments of both grotesque violence and bittersweet beauty.