When it comes to twisted-yet-amusing Christmas tales, forget Gremlins and Rare Exports or even Krampus. I cannot think of many examples that are as fascinating as ‘The Mystery of Christmas Lost!’ (Batman #285, cover-dated March 1977, but, according to Mike’s Amazing World of Comics, appropriately released on December 1976).

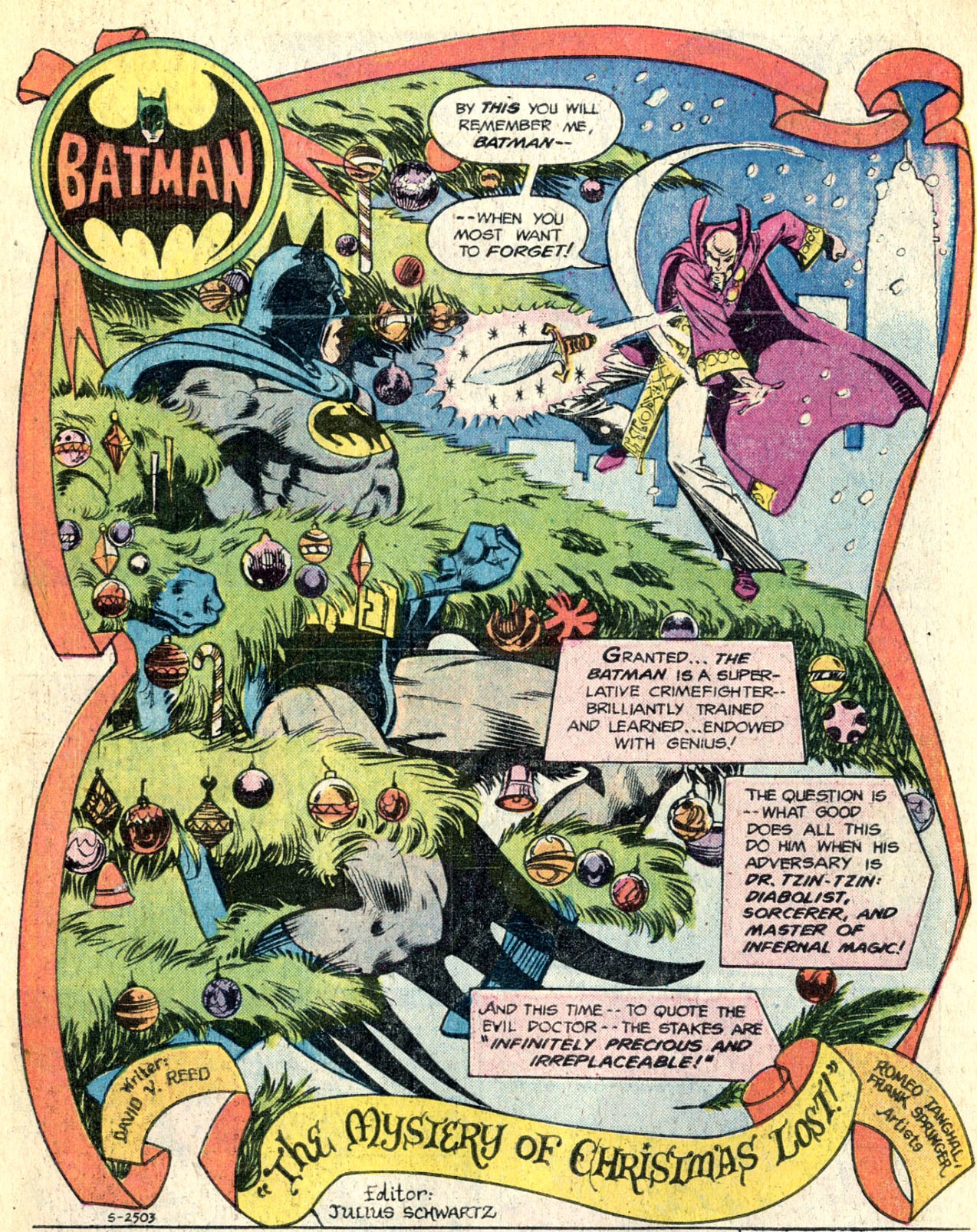

As you can tell from the splash page above, the most disturbing thing about this issue is that it stars Dr. Tzin-Tzin, a super-villain who comes across as a horrible orientalist stereotype (down to the onomatopoeic name, which sounds like a parody of oriental music).

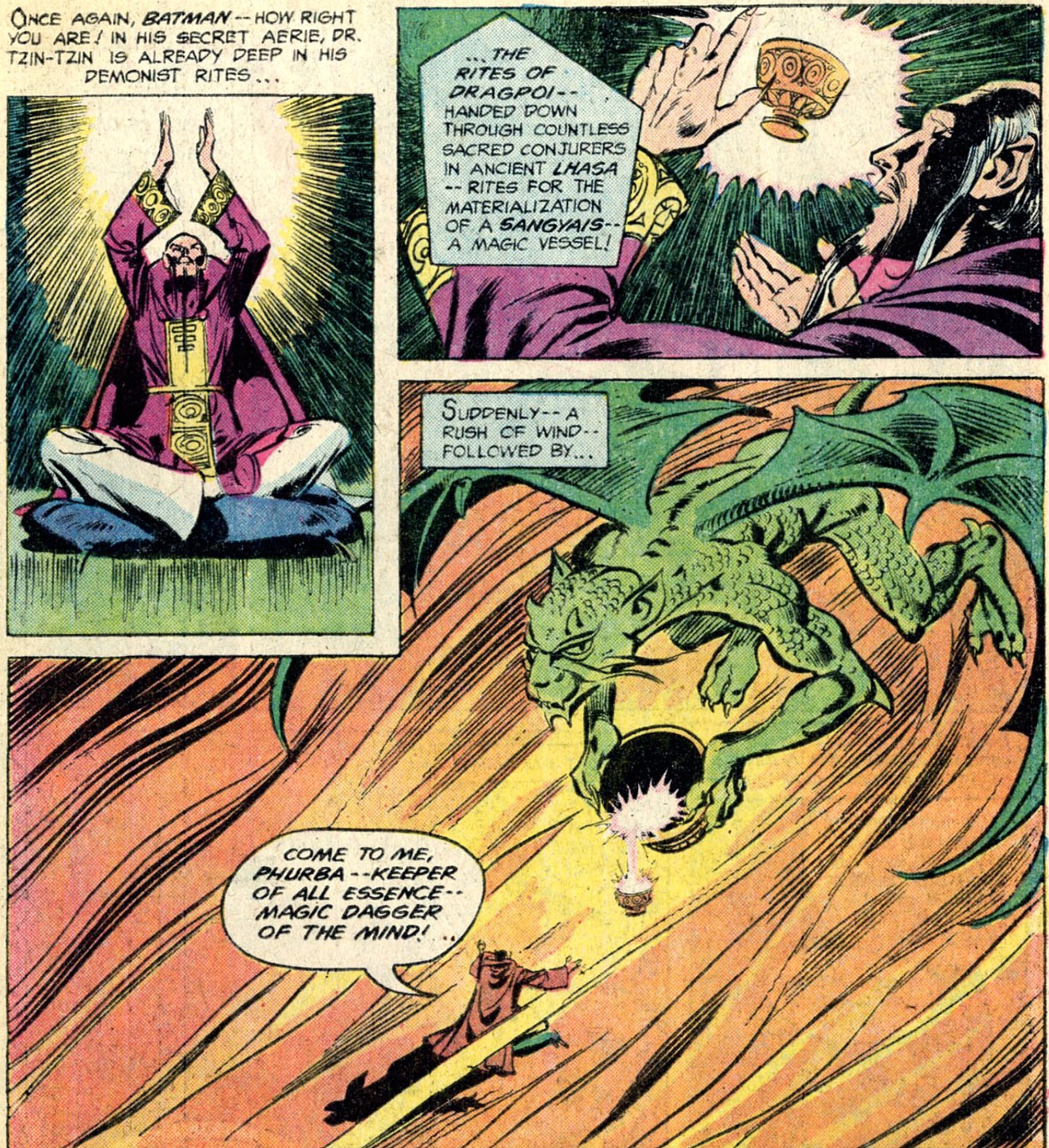

Introduced ten years earlier, in Detective Comics #354, Dr. Tzin-Tzin looks like an obvious take on Dr. Fu Manchu, the criminal genius created by British writer Sax Rohmer in the early part of the twentieth century. In previous appearances, we were told that Tzin-Tzin was an American raised by Chinese bandits who ‘adopted their ways,’ ‘spent years in Tibet steeping himself in their mystical teachings,’ and ‘then entered the western world to rob and pillage in a grand style!’ In other words, Tzin-Tzin fit into a long tradition of depictions of Asian culture as something utterly strange, irrational, and threatening. He essentially embodied enduring fears of the penetration and assimilation of said culture in the West.

Yellow Peril tropes weren’t just rooted in a prejudiced understanding of foreign customs as scary and exotic, but also in social phenomena within the United States, such as eugenic concerns about the purity of the white race, local workers’ competition with migrant labor, and the connotation of Asian communities with opium consumption and prostitution rings. Since the late 1940s, there was also a clear link to the widespread anti-communist paranoia, which looked at places like China, North Korea, and North Vietnam through a Cold War mindset. Along this line, Tzin-Tzin’s ability to absorb energy from those around him works as a metaphor for the rise of eastern power, while his mastery of hypnosis follows the obsession with brainwashing that had been all the rage at least since the release of The Manchurian Candidate.

Needless to say, this type of racist imagery has been used to justify the discrimination and oppression of Asians – and Asian Americans – for generations, which makes it pretty hard to accept a villain like Dr. Tzin-Tzin, even when enveloped by the fanciful art of Romeo Tanghal and Frank Springer…

It’s a shame, because as a character Dr. Tzin-Tzin is not completely hopeless. He is ultimately an evil version of Dr. Strange, a sorcerer with mysterious and outlandish powers so far beyond the reach of the Caped Crusader that Batman has no option but to somehow try to outsmart him. Conversely, the ‘diabolical wizard’ is not interested in tearing his opponent to bits (which he could easily do), but in having a victory of the ‘mind’ – breaking Batman’s heart and humbling him until he recognizes Dr. Tzin-Tzin as his master.

Tzin-Tzin’s heightened psychic force – which enables him to control almost anything, alive or inanimate – can be used in fun ways. Batman #285 opens with the ‘master of malice and mayhem’ in prison, where he ended up in the previous issue, after he had tried to literally steal the New Gotham Stadium (he had also replaced the Sphynx with an exact replica, for reasons that were never explained). In a quasi-meta touch, we first approach Tzin-Tzin’s cell via Batman’s private archives (anticipating the black casebook of Grant Morrison’s run, three decades later), which establishes straight away that, even for the Dark Knight, this is no ordinary foe:

Dr. Tzin-Tzin has been locked in a special prison cell, without TV surveillance (to keep him from manipulating the guards through the camera lenses) and with a random series of flashing lights and sounds (‘stimuli just sufficient to prevent the complete concentration of mind from which he gathers the Tsal or energy for his magical prowess’). Tzin-Tzin manages to escape by hypnotizing an ant (yes, a yellow-golden ant), eventually taking control of a whole horde of omnivore ants, enough to eat the mortar between the stones of the wall and to dislodge a stone block, which allows him to levitate the hell out of there.

When the guards try to stop him, the escaped prisoner shows them – and the readers – the extent of his power through this cheeky gag:

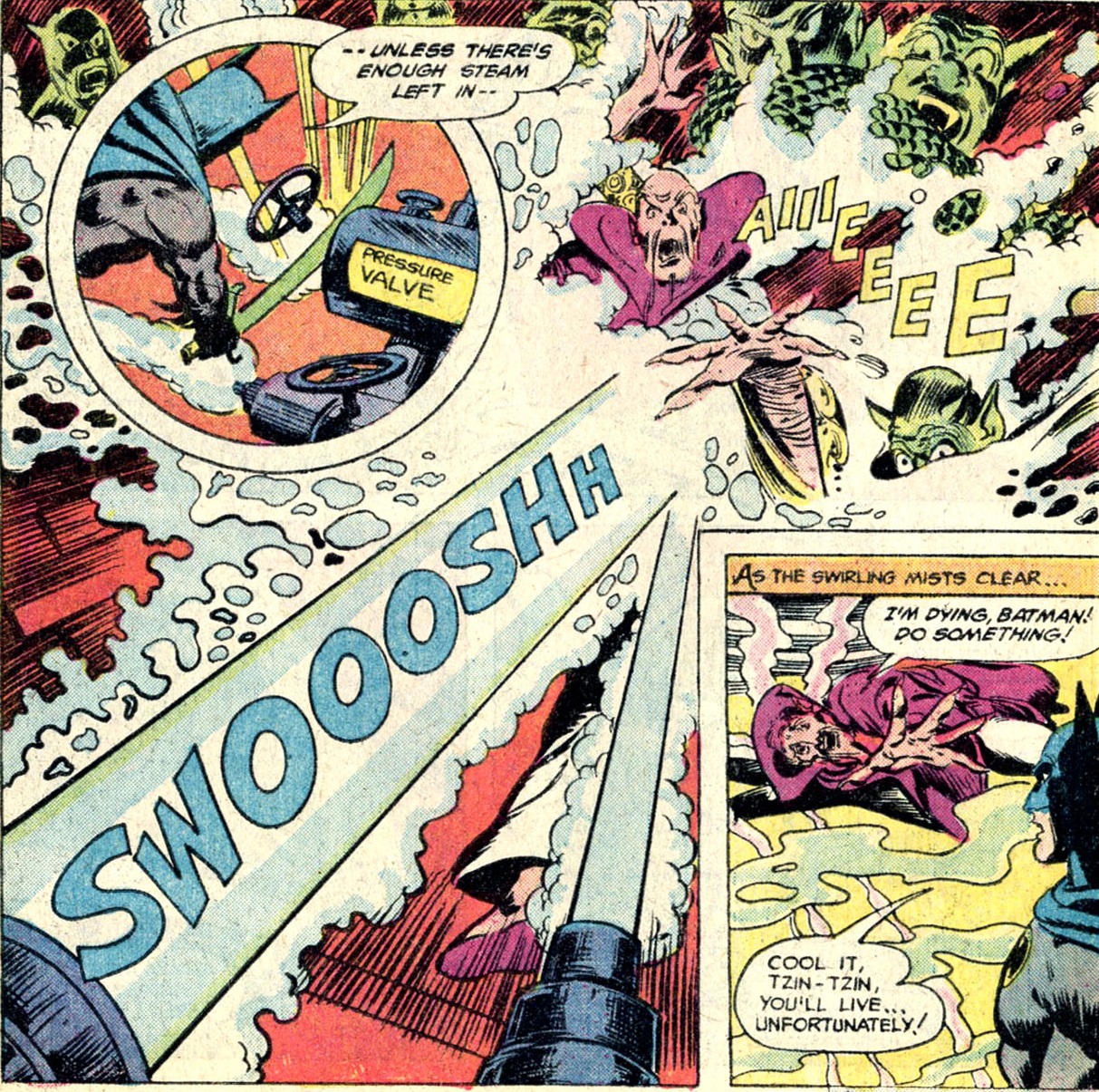

This is merely one of several quirky moments throughout the issue, a product of the fertile – if often intriguing – mind of David Vern (writing as David V. Reed). Vern keeps coming up with cool little scenes… The mind-controlled ants form a mocking message for Batman in the abandoned prison cell, which turns into a threat through the sudden addition of a question mark. Later, the Dark Knight fights a bear hidden in a Christmas tree, whose branches seemingly come alive and start to choke him before Tzin-Tzin speaks to him through a bauble. In a neat instance of detective work, Batman deduces the villain’s hideout based on the amount of snow on top of a steam conduit.

The art is somewhat uneven, but it too is peppered with occasional gems, like this bit from the aforementioned bear-fighting sequence:

Between the close-up with the circular red border that looks like a tree ornament and the swinging thrust of the larger panel – which leads our eyes down and then up again towards the bear’s moving head – the image creates a disorienting vibe, perfectly suited for a scene in which Batman himself is confused as to where reality ends and illusion begins.

It’s not just the small moments. There is actually a good story here. Because Dr. Tzin-Tzin wants his triumph to take place in what he considers to be his realm (‘the world of the substantial… the intangible!’), he explains to Batman that he plans to rob Gotham City of ‘something infinitely precious… irreplaceable… something you can never recover – because it exists only in the mind!’

Specifically, Dr. Tzin-Tzin uses the forgetfulness elixir of Nepenthe to rob Gotham of the notion of Christmas, taking away the awareness of that holiday from everyone except the Caped Crusader, who is condemned to live with the knowledge of a joyful celebration everyone else has forgotten (i.e. how Fox News pundits imagine they live every year, around December).

Following Tzin-Tzin’s spell, on Christmas Eve everyone becomes borderline incoherent (Dick Grayson, for example, doesn’t realize why he’s in town and keeps losing his train of thought when talking about it). The citizens’ inability to concentrate – psychataxia – mirrors the punishment Batman and the Gotham authorities had sought to impose on Dr. Tzin-Tzin, making this an inspired revenge plot. Then again, Tzin-Tzin doesn’t seem to care about anyone other than Batman, which suggests that he messed up the minds of millions of people just to get to one guy, which is even more vicious.

Moreover, even though the comic doesn’t mention it, presumably things would remain significantly bewildering for Gotham citizens in the future, since their brain had basically become unable to process an omnipresent reference in their country’s pop culture. Plus, you know, the economy would possibly take a plunge in the absence of the season’s consumerist binge!

None of this happens, though, because Batman defeats Dr. Tzin-Tzin by taking advantage of the villain’s obsession with him. Since Tzin-Tzin can only feel victorious if his opponent is aware of what happened, Batman pretends to have forgotten about Christmas as well. When Tzin-Tzin tries to double the dose of the spell’s antidote, he lets the Caped Crusader come within striking distance and destroy Nepenthe’s elixir, thus reinstating the memory of Christmas throughout the city. Cue The Vandals’ ‘Nothing’s Going to Ruin My Holiday.’

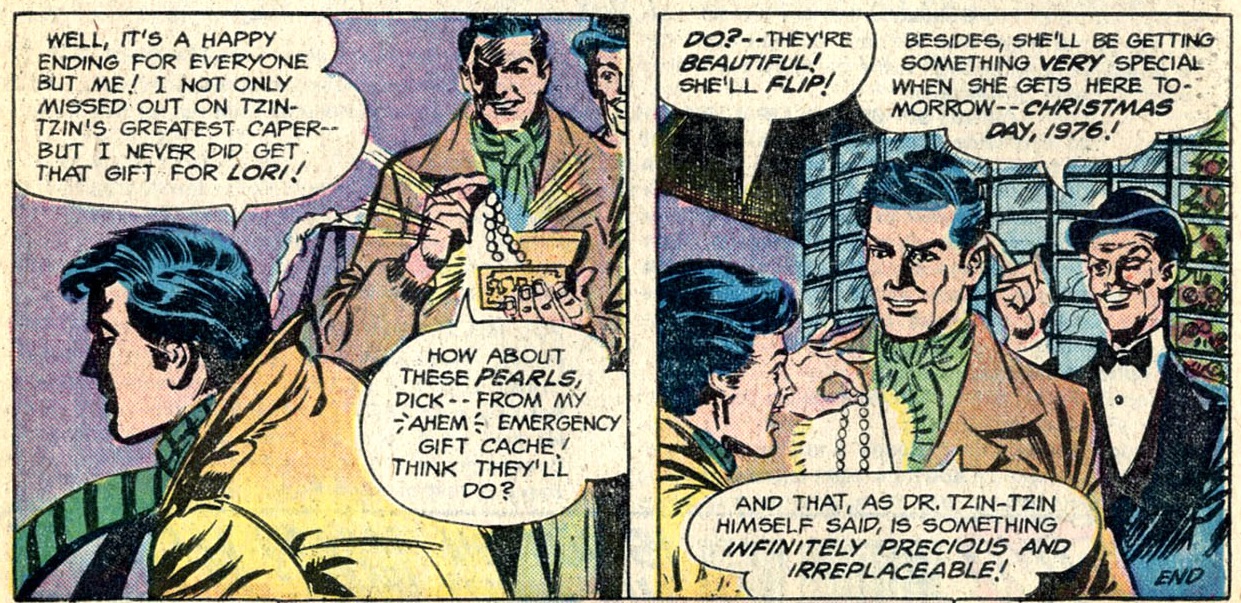

Although Batman’s main worry seemed to be the onset of mass confusion, he is clearly happy about having saved everyone’s holiday spirit. He even suggests to Dick and Alfred that they go outside and listen to the carillon concert from the cathedral. The final pages reinforce the feeling that the most important aspect of the story’s resolution is Gotham’s continuing ability to celebrate Christmas and its rituals, including the exchange of gifts between loved ones (such as Dick’s girlfriend, Lori, the only woman mentioned in the entire issue).

Like I said, the comic can leave a sour taste in your mouth, especially if you’re uncomfortable with narratives about Christianity being under attack by offensive orientalist caricatures. Unlike John Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China, ‘The Mystery of Christmas Lost!’ doesn’t even counterbalance its stereotypical villain by subverting the role of the Caucasian hero (in Carpenter’s tongue-in-cheek adventure, Jack Burton isn’t just a bumbling fool, he is effectively Wang Chi’s sidekick without realizing it – but in Batman #285 there is no question about who the main hero is).

That said, there’s a different way to read this issue. After all, Dr. Tzin-Tzin is not supposed to be a purely sinister Asian madman – he is an American emulating the trope of the sinister Asian madman. We can choose to see him less as a racist caricature than as a caricature of racism: he’s not Fu Manchu so much as a guy who wishes to be Fu Manchu and deliberately tries to look and act like him. Tzin-Tzin therefore does not represent Asian culture, but the way the West has imagined that culture (which explains his silly choice of name). In fact, he acknowledges his hybrid influences in the comic itself, telling Batman how he implemented his evil scheme by ‘joining ancient Tibetan lore and western technology’ (i.e. a steam plant).

If we look at Tzin-Tzin as an ugly case of cultural appropriation, it makes sense that he would seek to erase Christmas, since that’s what he envisions an eastern super-villain would do, perhaps as payback for all the forced Christian conversions imposed by western colonialism. That being the case, Batman’s actions can be seen as punishing not only an attack against his own cultural background, but also the defamation of another culture.

In all probability, this is not what David Vern or editor Julius Schwartz had in mind, but I like to think that, when the Dark Knight burns the skin of Dr. Tzin-Tzin, it’s his way of fighting the very notion of such a racial travesty. It also helps justify Batman’s particularly harsh words afterwards…