Back when I discussed Doug Moench’s 1980s Batman run, I singled out as its most striking features Moench’s literary emphasis on symbolism, characterization, politics, and intertextuality. This week, I’ll zoom in on one story in particular which powerfully combines all these elements. The two-parter published in Batman #372 and Detective Comics #359 (both cover-dated June 1984) is a noir-tinged yarn oozing with bold social commentary, set in the world of professional boxing.

The first thing to note is that the covers of both issues are quite misleading, even if taken as allegories. Returning readers might recognize the villain, Dr. Fang (a theatrical gangster who is both an ex-boxer and an ex-thespian), but they would be wrong to assume that these comics concern a direct confrontation between him and the Dark Knight. Instead, we get one of those Eisner-esque tales where Batman is practically a supporting character in somebody else’s drama.

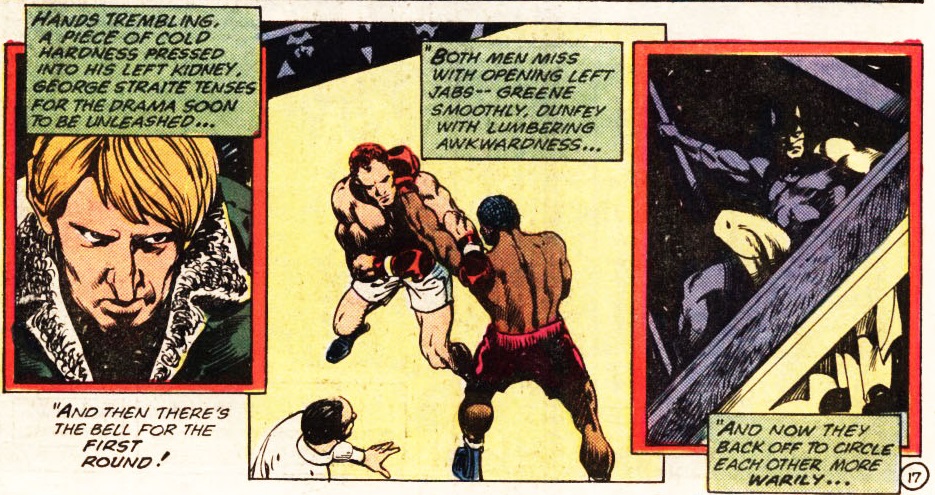

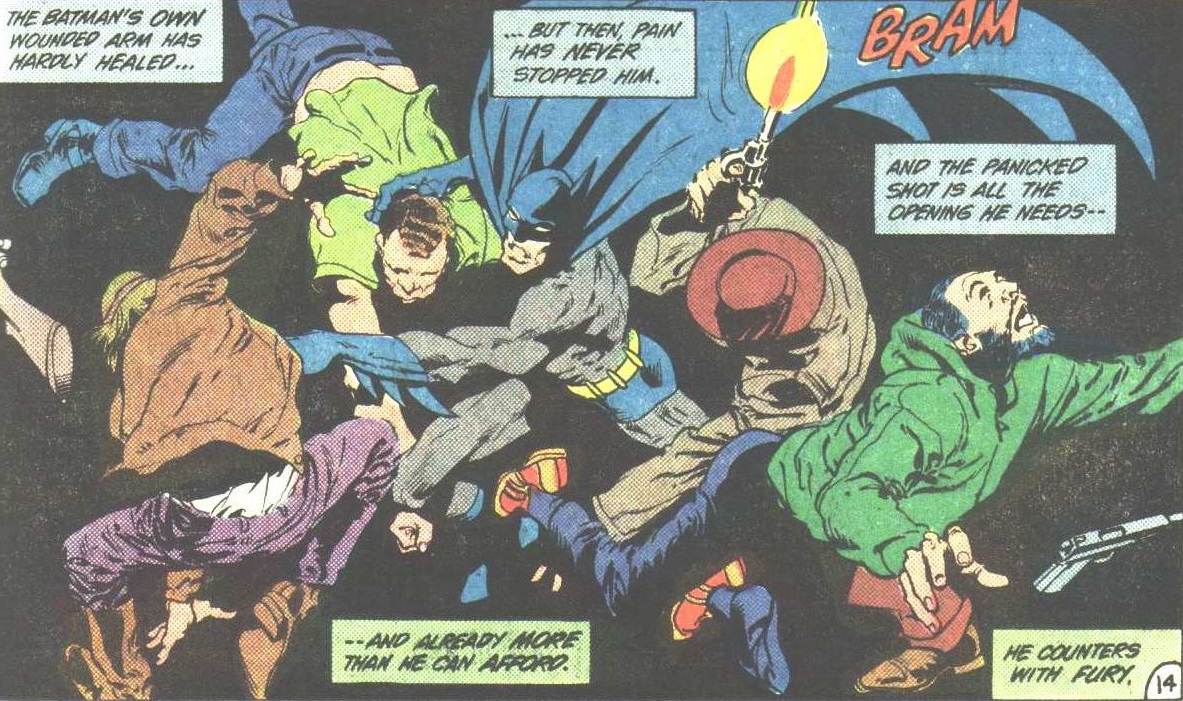

In Batman #372, Dr. Fang sets up a big match between the heavyweight champion Michael Greene and the underdog Tommy Dunfey, with old-school idol Jake DeMansky as referee. He then fixes the fight by blackmailing the champ (off-page), hoping to earn a fortune by betting on Dunfey. That’s the premise anyway, although Fang and his plan soon move to the background as the comic digs into the motivations of the boxers and the implications of the match for those around them. As for Batman, we actually see very little of him – he only shows up in a couple of brief scenes before partly saving the day by preventing a murder attempt on DeMansky, albeit not without getting shot in the arm himself… Notably, he isn’t able to save Greene, who gets killed by Fang’s henchman for refusing to throw the fight at the last minute.

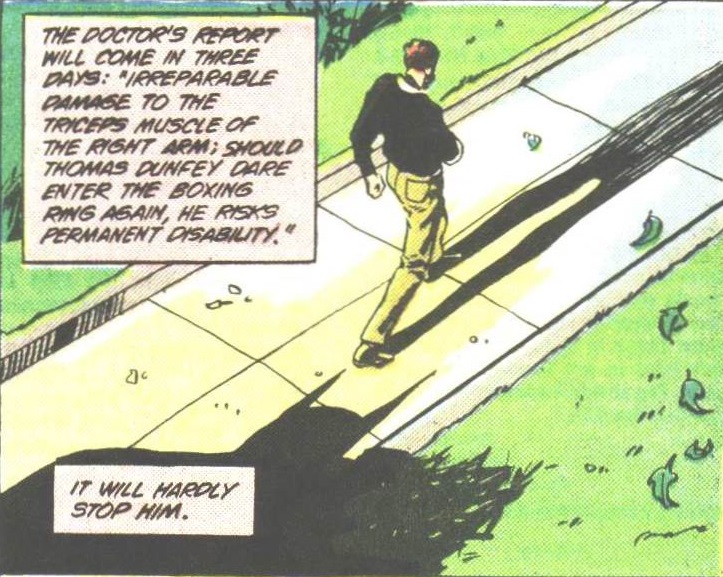

Detective Comics #359 delivers a more straightforward thriller, as Dunfey – out to avenge his former rival now that he realizes the extent of the fix – teams up with the Caped Crusader to find and take down Dr. Fang. As is often the case in Moench’s two-parters from this era, the whole thing is neatly symmetric: again, the climax involves someone getting shot in the arm and, again, it takes place in a ring, now with Dunfey going up against Fang while Batman, once more, keeps busy outside:

Let’s get the intertextual stuff out of the way. As far as I can tell, these comics aren’t riffing on any one work in particular, although their setting and atmosphere do evoke classic boxing pictures. This is a subgenre that goes all the way back to the silent era (even Alfred Hitchcock did one, The Ring). From Raging Bull to Million Dollar Baby, the most acclaimed pictures tend to be dramas that aren’t really about the sport itself but more about fighting as a metaphor for the characters’ aspirations, often telling sagas of anti-heroes who rise and fall… and, sometimes, rise up again. The most well-executed example of this formula is probably Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul (which the Rocky franchise has been ripping off for decades…). Revolving as they do around a deadbeat lumpen, I suppose these two comics sort of end up channeling Robert Wise’s The Set-Up and John Huston’s Fat City.

At their core, Batman #372 and Detective Comics #359 are character pieces. They’re quite original ones, though, since the characters they focus on aren’t just new, but oddly grounded and mundane for a superhero comic. I can see how unsettling this may feel for some fans, as Batman gets so little space in the first part of the story and he’s not even the one who takes down the main villain in the end. That said, Doug Moench’s rich characterization – nailed by the gritty art of Don Newton (who co-plotted the first issue) – pays off beautifully, both by bringing tension to the climactic fights and by contextualizing the weight of the Dark Knight’s actions.

In typical fashion, a big chunk of Moench’s script is built around wordplay. The title of the first issue – ‘What Price, the Prize?’ – works on multiple levels, since there are very different stakes (or ‘prices’) for each character in the climactic boxing match for the championship belt (the ‘prize’). Moreover, the phonetic similarity between the two words keeps coming up throughout the comic (along with the similarities between ‘champ’ and ‘chump’), highlighting the connection between the two things. The title of the second issue – ‘Boxing’ – also has various meanings, referring to the sport itself as well as to the ways in which characters are trapped (or ‘boxed’) by their identities. The latter point is made right in the opening page, set at Michael Greene’s funeral, while adding yet another, more literal, meaning: namely the fact that Greene will now spend the rest of his days in a box (his coffin).

Ironically, despite this leitmotif, the second issue appears less tight, because a few scenes are devoted to unrelated subplots, including one about Jason Todd and Alfred’s daughter, Julia Pennyworth. Nevertheless, the dialogue does try to relate those detours to the ‘boxed’ theme, namely by having Julia muse about how ‘we’re all contained by what we are.’

At the risk of pushing this reading too far, the fact that Don Newton’s pencils – inked by Alfredo Alcala and Bob Smith, with colors by Adrienne Roy – tend to go for rigid rectangular panels (with a few exceptions, like the cool bat-shaped splash on page 9) reinforces the notion that everyone is constantly trapped by their surroundings, unable to break away from their identity.

These threads brilliantly come together in the final panel:

(Notice how Thomas Dunfey – the most fleshed out character and, therefore, the story’s true protagonist – is at the center of the image, while Batman – who played more of a supporting role – is a shadow silhouetted on the sidewalk. This is another rhyme with the previous issue, whose final panel was framed from a similar perspective… and where a shadow was all we saw of Batman as well.)

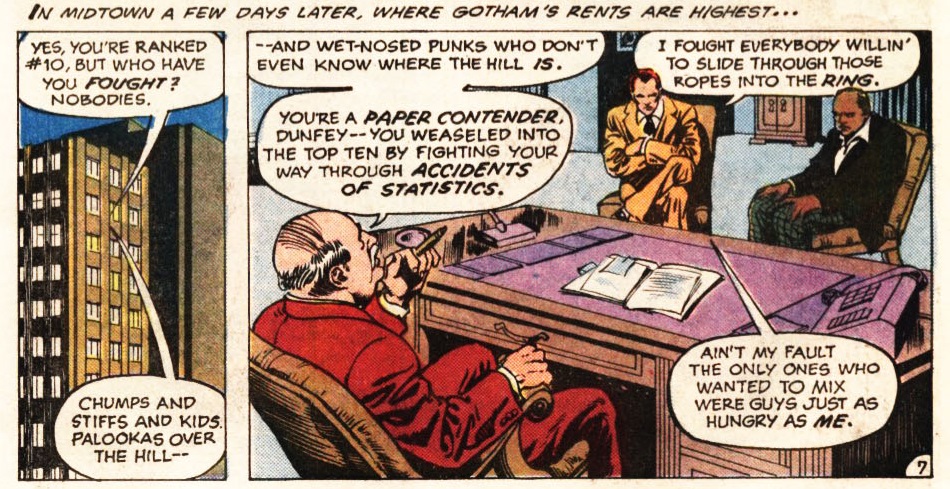

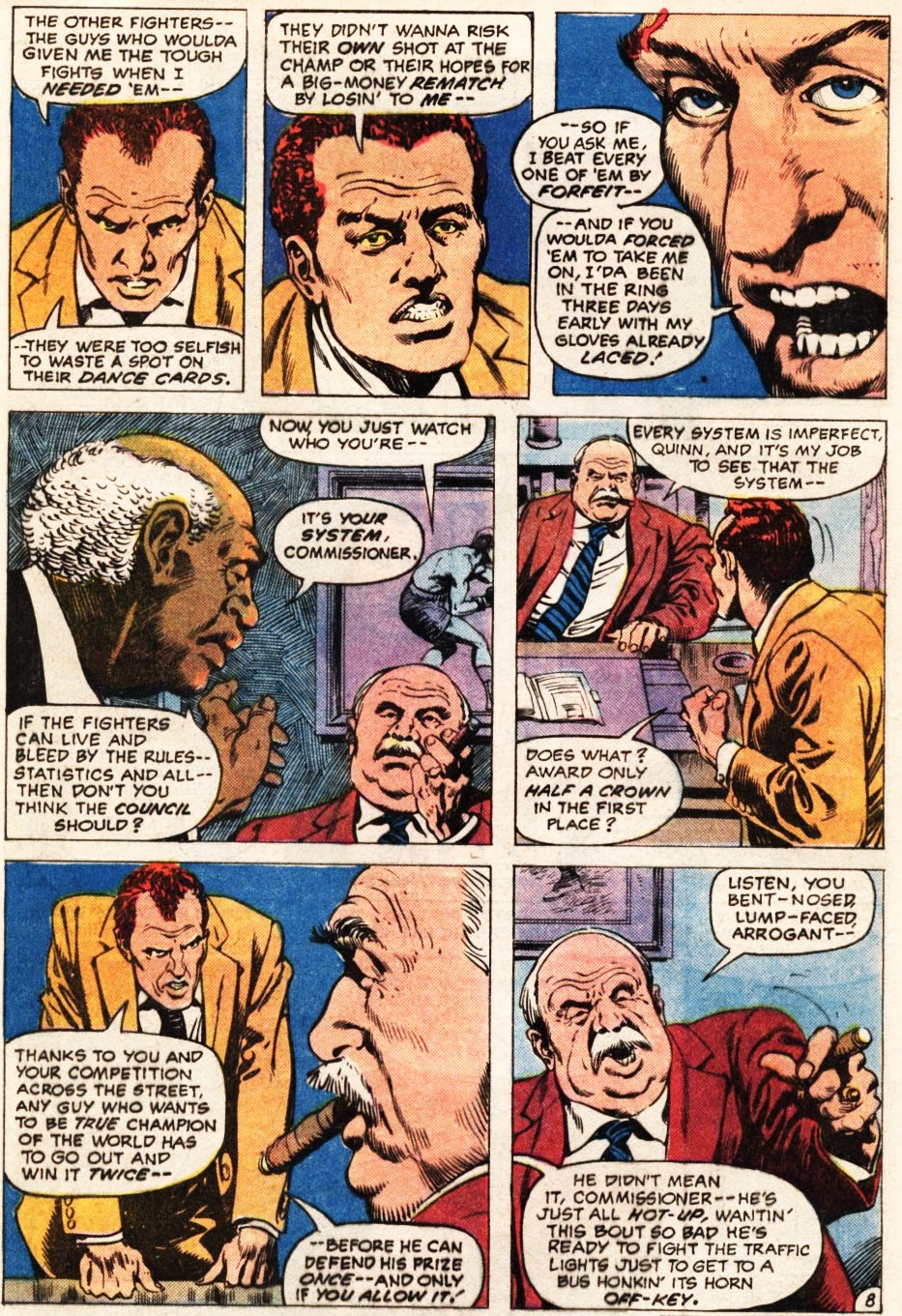

The ‘boxed’ motif is more than a narrative game – it also ties into the comics’ politics. The whole boxing system is set up like a tight contraption, as shown in this scene where Tommy Dunfey and his coach, Rudy Quinn, try to negotiate their way into fighting the champ:

I love the colorful turns of phrase. Moench uses the sport’s slang in a way that really gives us a sense that these characters have been around it for long. (This is reminiscent of Mark Robson’s underrated film noir The Harder They Fall.)

The dialogue sounds a bit more ham-fisted later on, during a conversation between Bruce, Alfred, and Julia about the pros and cons of boxing. Regardless, it’s still interesting to see a vigilante-themed comic book engaging so openly with the masculinist appeal of violence:

(Such a smooth mise-en-scène in that last panel, where it seems like the Bat-Signal is springing from Bruce’s mind…)

(Such a smooth mise-en-scène in that last panel, where it seems like the Bat-Signal is springing from Bruce’s mind…)

That said, the story’s most prominent political theme has to do with race in the boxing world, as Michael Greene finds himself ‘boxed’ in his black skin, just as Tommy Dunfey and Jake DeMansky are ‘boxed’ by their whiteness.

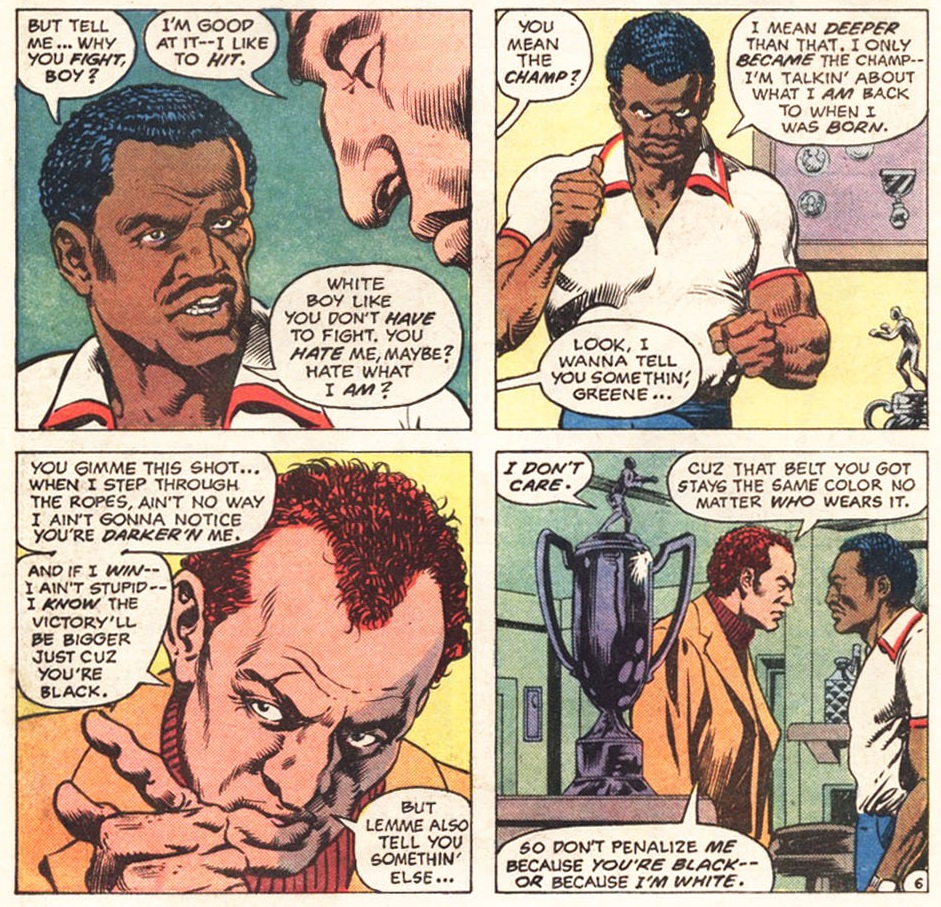

Notably, the racial theme is not explicit from the start, but it gradually creeps into the forefront. The first time it becomes clear is when Dunfey pays a visit to Greene and tries to convince the champion to fight him, even though he is ranked #10:

Even as the issue becomes more central to the story, Moench manages the rarity of writing a comic book about racial tensions where the topic is dealt with in a refreshingly mature way, with each character relating to it differently. The African-American Rudy Quinn shamelessly convinces the commissioner of the World Prizefighting Council to allow the match by asking him if he wouldn’t like a chance to see Dunfey destroy ‘the black champion of the world.’ (The silent panel with Quinn and the commissioner starring at each other after this exchange is stirring.) The media rides the wave by labeling Dunfey the ‘underdog white hope.’ Most people we see seem to assume Greene is obviously stronger than any white boy. The most extreme case is George Straite, a white supremacist willing to kill DeMansky just to prevent his idol from enabling Dunfey’s humiliation by a black man – the scenes in Straite’s apartment (a ‘haven of white flesh and dark thoughts’) would sound almost caricatural if not for the recent reminders that people like this are still around.

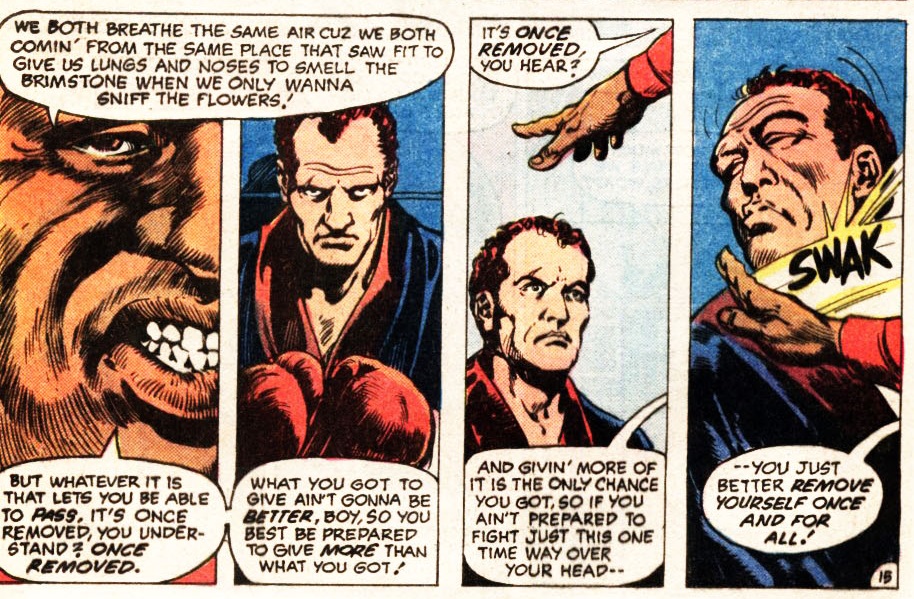

My favorite bits are between Tommy Dunfey and Rudy Quinn, who frankly recognize the racial undertones of the upcoming match. Once again, Quinn is not above drawing on racist imagery to get his way, delivering reverse psychology in the form of a harsh motivational speech about the superiority of the champ’s genes, at least as far as boxing is concerned:

(That final panel gets to me every time, as you can see Quinn has serious doubts about Dunfey’s chances in the ring…)

(That final panel gets to me every time, as you can see Quinn has serious doubts about Dunfey’s chances in the ring…)

I suppose you could consider racism to be the real villain here. That would recast Batman as a more conventional hero, since he is the one who stops the violent racist George Straite (in a fight that, in typical Moench style, mirrors the events in the ring). At the same time, this story appears to be less about defeating racism than about pointing out its prevalence in society, in multiple and insidious ways, making it damn hard to escape.

After all, it’s not just Dr. Fang, Rudy Quinn, the boxing commissioner, and the media who exploit racist feelings. The Dark Knight himself benefits from a racially motivated – and horribly worded – tip while looking for Fang and his henchman, Woad… leading to the most cathartic punch of a comic packed with punches: