Once again, the folks at Dead Reckoning have sent me one of their graphic novels to review: Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat, in which Ben Towle spotlights the historical role of different creatures in various wars. Like last time, I thought it might be fun to put the book into context, namely by placing it alongside other cool war comics about animals. After all, there are a number of great ones out there, as the clash between animals’ natural fierceness and their ideological innocence (in regards to the motivations of human warfare) lends itself to powerful drama, inventive action, symbolism, and even comedy!

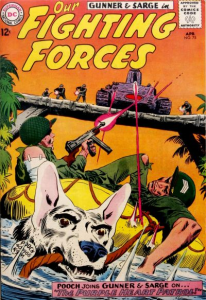

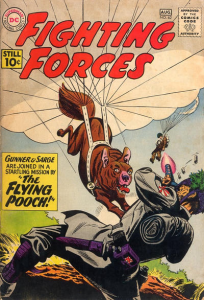

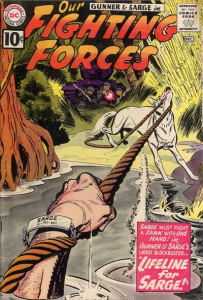

The tradition of throwing animals into the battlefront actually goes way back… In the 1950s and 1960s, for instance, creators militarized the Lassie formula in comics such as The Adventures of Rex, the Wonder Dog and the recurring ‘Gunner & Sarge’ strip from Our Fighting Forces:

At their best, these series combined the grim reality of war with two-fisted adventure, achieving a fine balance that is not entirely unlike the one in John Sturge’s The Great Escape or in those kickass WWI episodes of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. At their worst, they tended towards propaganda and sentimentality, dehumanizing foreign enemy combatants while schmaltzily playing up the empathy towards the canine characters. As far as I’m concerned, the best take on this sort of premise only came in 1979, with Battle Action’s running feature ‘War Dog,’ which followed the journeys of a German Shepherd in World War II, told in a much grittier and drier – if often exciting – tone.

By the time ‘War Dog’ came out, a whole other trend had already begun to emerge in the comics that shared the shelf space with Battle Action on the British newsstands. With a much more caustic understanding of the animal kingdom (not to mention of war itself), rather than focus on dogs’ usefulness and loyalty towards their masters, Pat Mills and Ramon Solá worked together on a string of gory thrillers – drenched in deadpan black humor – about animals fighting back against cruel, selfish humans. With their heart openly on the side of nature, they invited readers to root for fierce creatures on deadly rampages.

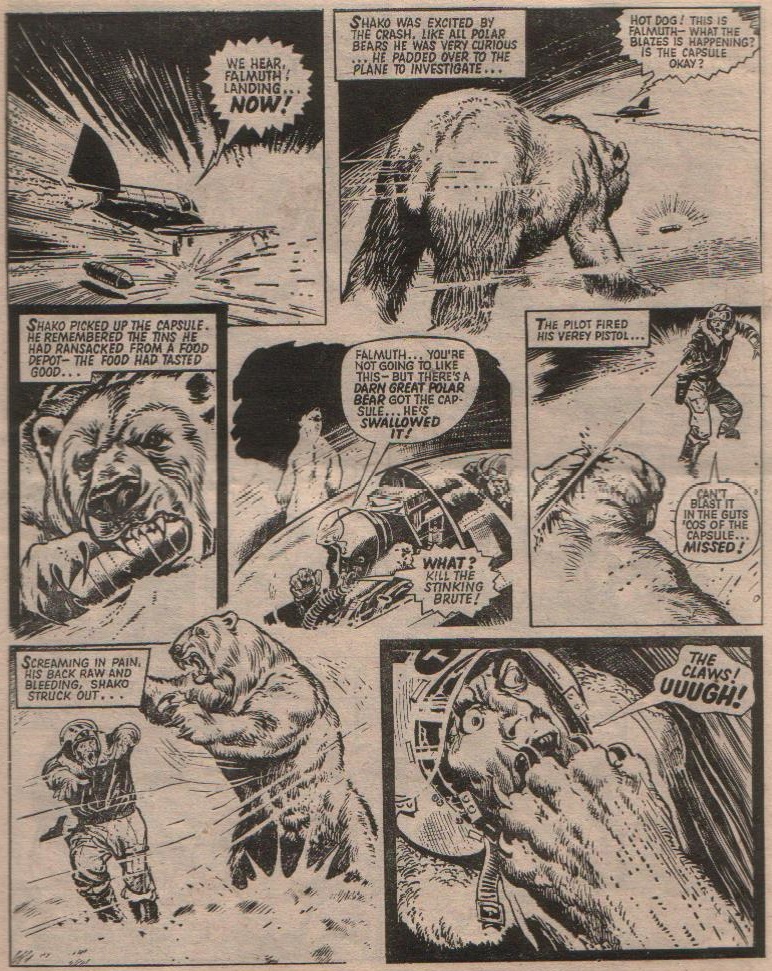

2000 AD #20

2000 AD #20

Part of that crop, the cult-favorite Shako follows a man-eating polar bear who finds himself on the CIA death list after unknowingly swallowing a top-secret capsule that, if it falls into enemy hands, risks shaking up the balance of power in the Cold War… True to the formula, the American agents come after the titular bear and keep getting slaughtered in vicious, sometimes ironic ways.

Co-created by writer John Wagner (who shared Mills’ fearless willingness to embrace the ridiculous) and with further stark artwork by Dodderio, Cesar Lopez-Vera, and Juan Arancio, Shako was originally published on the pages of 2000 AD. Like many of the other series in this anthology’s earlier years, Shako is anything but subtle, tasteful, or particularly thoughtful, but its creators display a characteristic instinct for raucous entertainment. And yes, the bear comes damn close to starting World War III!

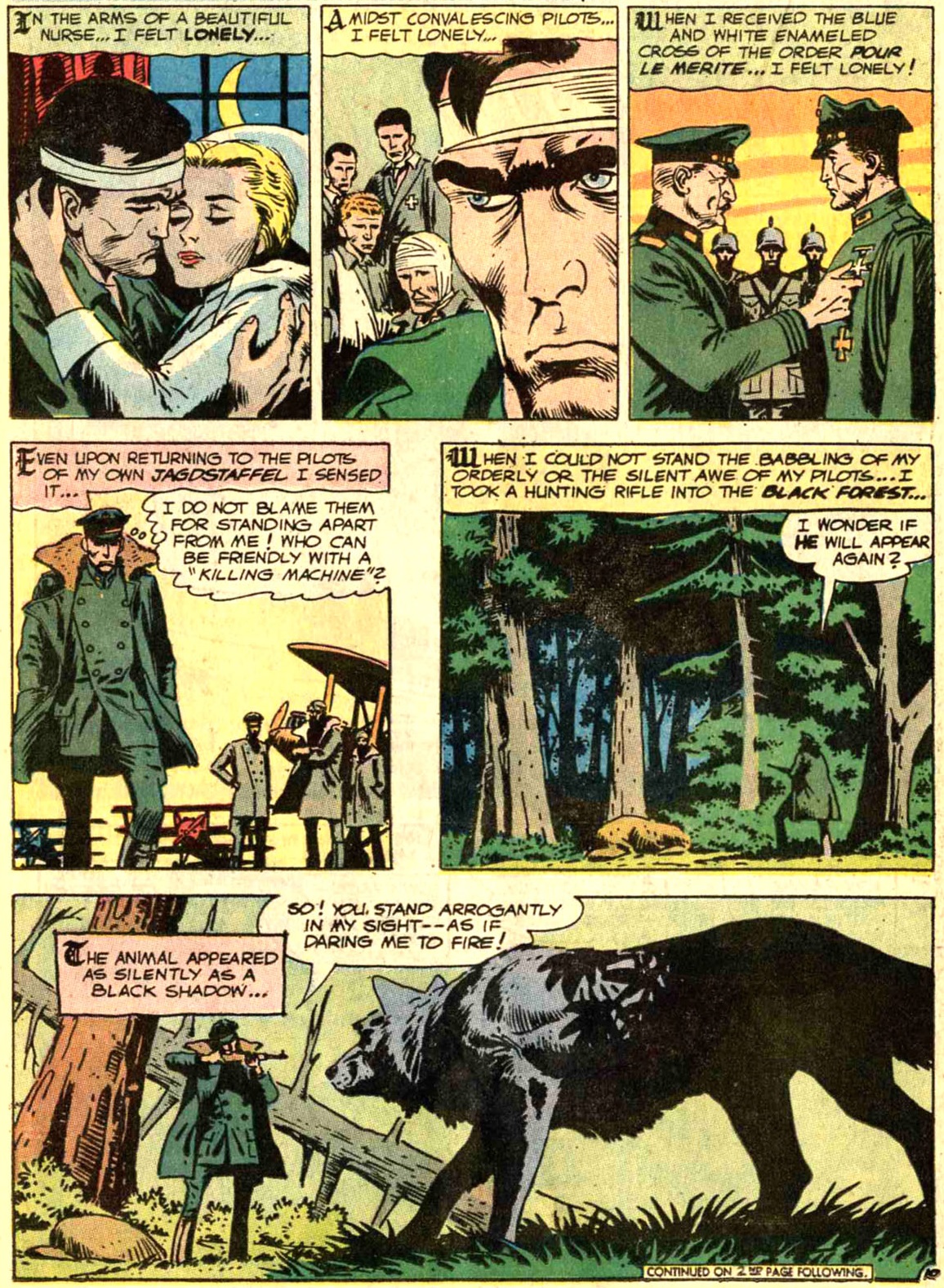

For a more melancholic take on war, the obvious alternative would be DC’s Enemy Ace. Created in 1965 by Robert Kanigher and Joe Kubert, these comics focused on the chivalrous German fighter pilot Hans von Hammer (aka the Hammer of Hell), whose troubled soul served both to evoke compassion even for historical enemies – in this case, for those who fought for the losing side of World War I – and to tell tales about the dark morality of military conflict (without directly challenging American heroism). One of my favorite choices in this series was how the protagonist’s loneliness was conveyed through the fact that the only creature he felt comfortable with was, quite literally, a lone wolf:

Our Army at War #151

Our Army at War #151

(Get it? Part of him feels like a wolf, which makes him a metaphorical werewolf, so of course he is drawn by the full moon. Comics!)

This black wolf kept reappearing throughout the years, usually popping up halfway through each story to help Hans von Hammer solve his latest moral dilemma or just generally reconcile him with all the death he’d caused in the sky by reminding him that killing was a part of nature. The comparison between the two was pretty explicit and quite twisted (the wolf killed to hunt or in self-defense, not for nationalist or imperialist ideals), the implication being that Hans used the beast to rationalize and somehow justify his own anti-social impulses, which gave these moments an almost poetic sense of despair.

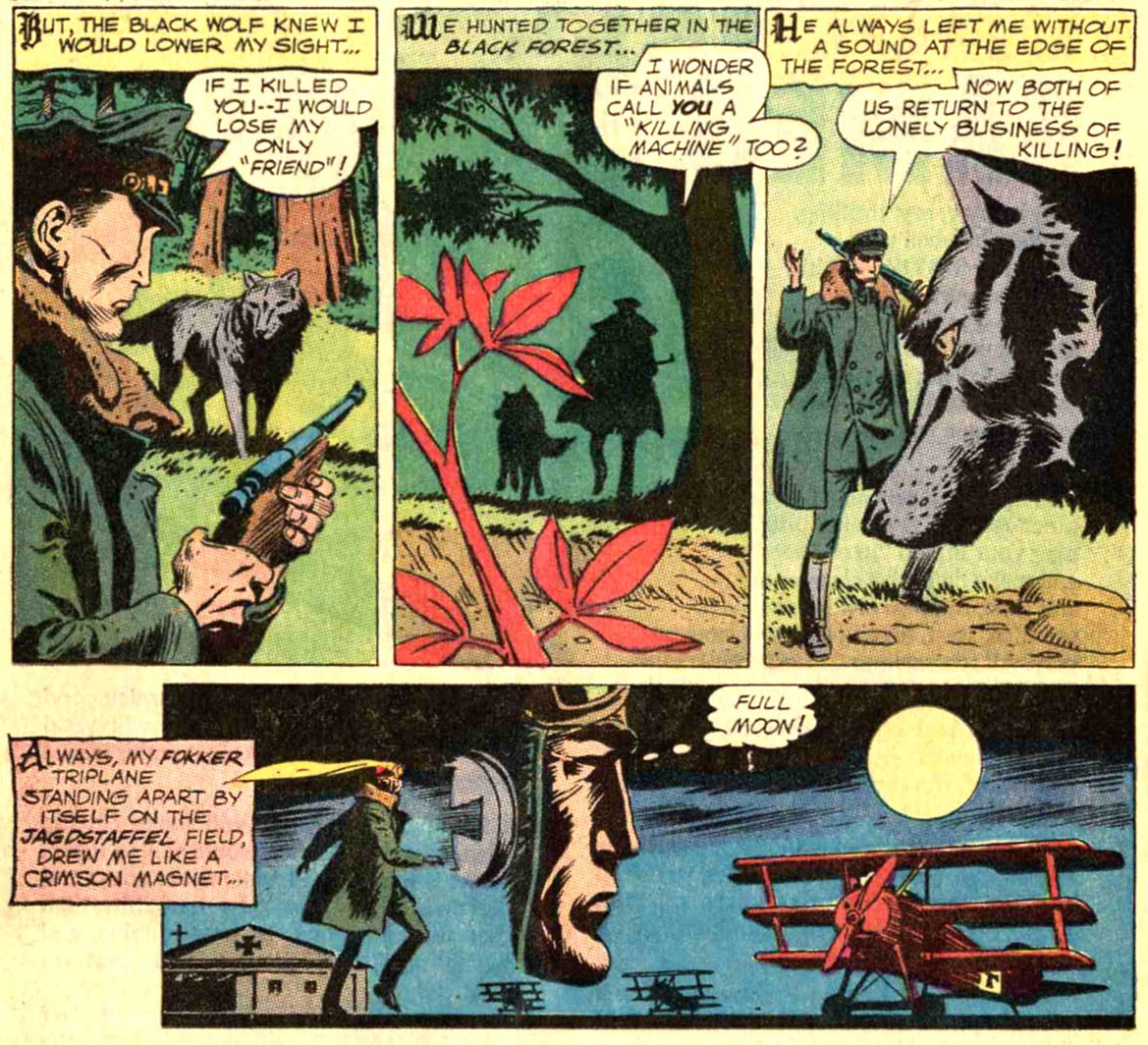

In 1969’s ‘Luck is a Puppy Named Schatzi!,’ Hans von Hammer briefly adopted a cute little puppy, letting a glimmer of hope and positivity into his life. The balance between his more compassionate and his misanthropic sides was beautifully illustrated by an encounter between the titular puppy and Hans’ other four-legged companion:

Star Spangled Stories #148

Star Spangled Stories #148

And if you think Schatzi survived this tale, it means you’re not familiar enough with Enemy Ace’s views on what warfare does to any symbol of innocence…

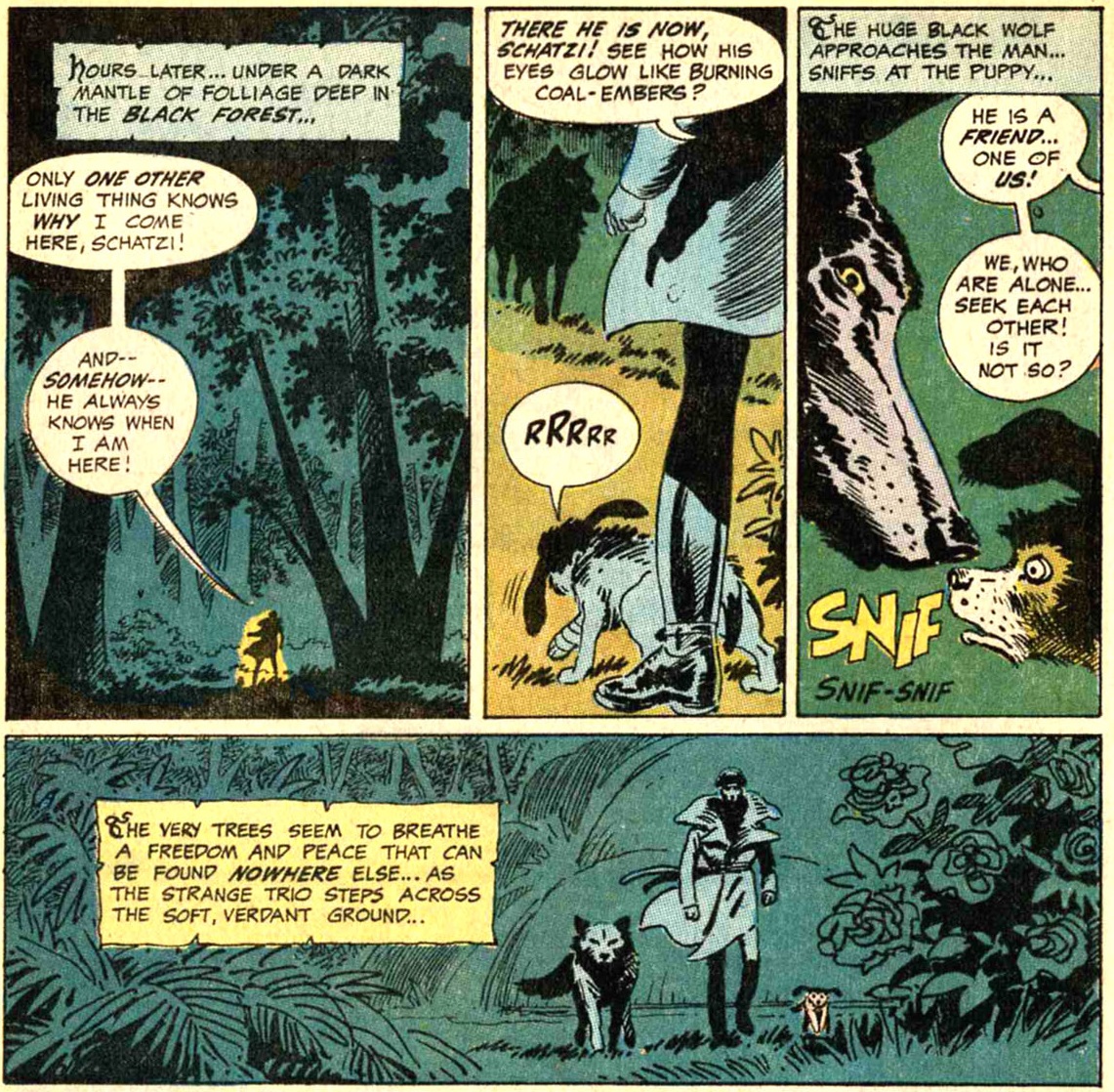

Indeed, as Aesop established thousands of years ago, animals don’t always have to represent just themselves. Art Spiegelman famously used humanoid mice, cats, pigs, etc. to depict the Holocaust in his massively acclaimed Maus, which chronicled how his father survived Auschwitz.

Maus

Maus

To be fair, Maus is as much about WWII and the war’s legacy/memory/trauma as it is about Art Spiegelman’s difficult relationship with his father, blending oral history-based reconstitution with psychoanalytical autobiography.

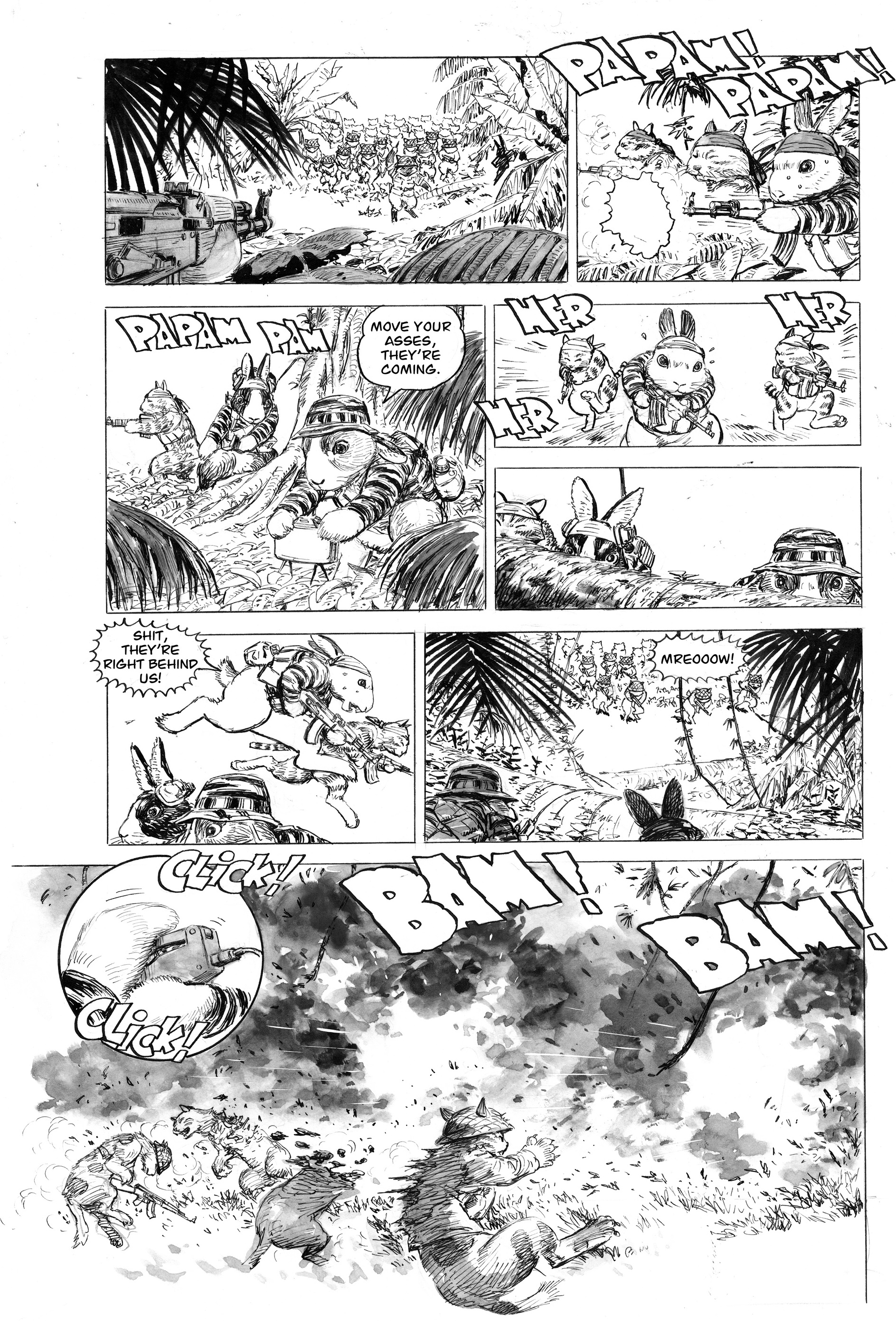

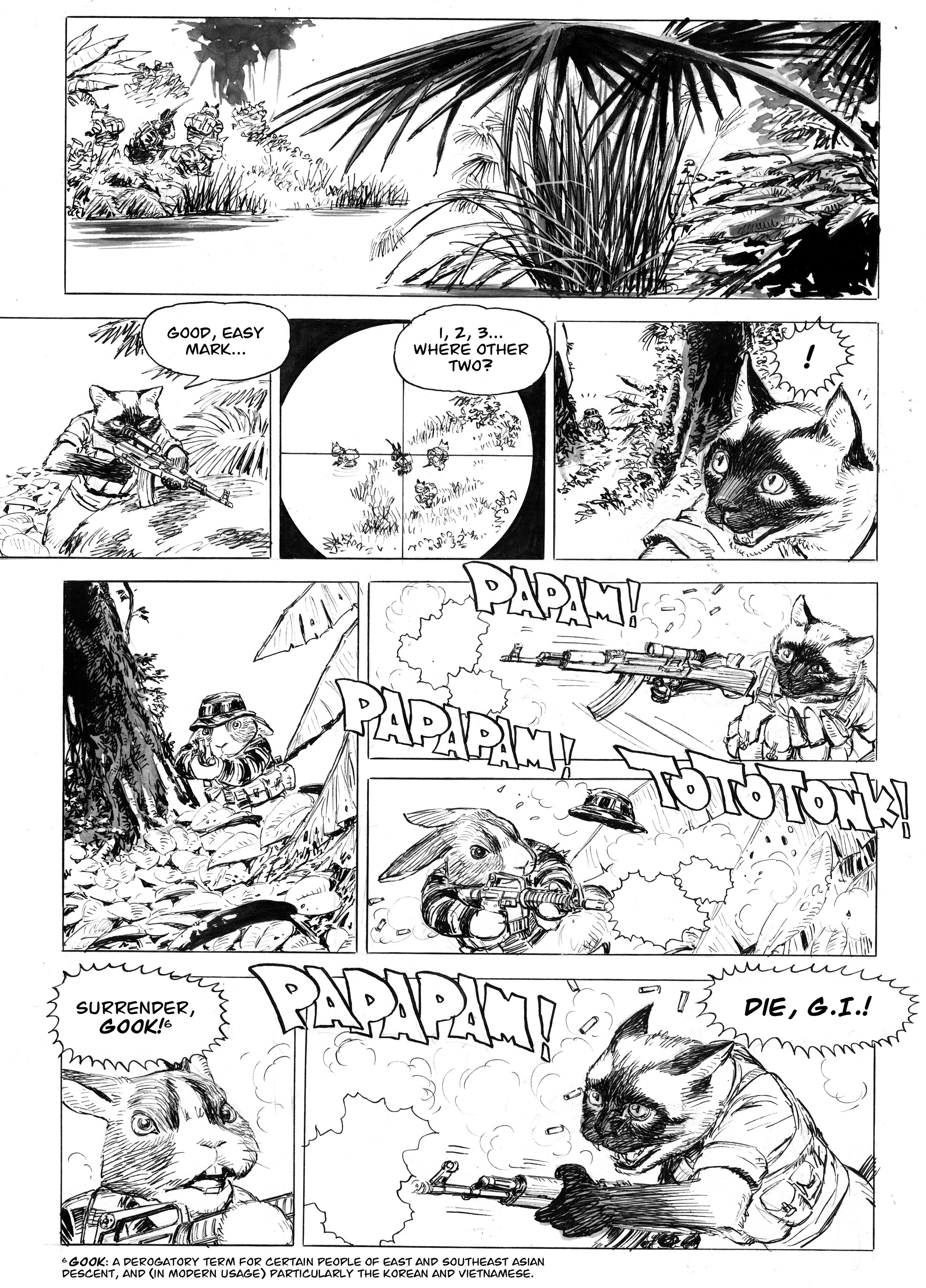

With a less neurotic and introspective attitude, Motofumi Kobayashi, rather than have felines stand in for Nazis, had them stand in for Vietnamese and fight adorable American bunnies:

Cat Shit One #1

Cat Shit One #1

The three-volume manga Cat Shit One obviously gets a lot of mileage out of the oddness of watching the atrocious Vietnam War fought by extremely cute creatures (who, as you can see above, swear a lot and brutally slaughter their enemies). Like Spiegelman, Motofumi Kobayashi also counterbalances the harrowing historical reality with surprisingly playful touches, including the introduction of other animal species, such as bears (Soviets), pandas (Chinese), and chimpanzees (Japanese). In fact, from what I gather, the choice of recreating the United States’ soldiers as bunnies is a pun on the Japanese word for rabbit, ‘Usagi’ –> USA G.I.

Kobayashi plays up the sense of oddness by injecting realism into this surreal scenario. As a writer, he delivers detailed accounts of scrupulously researched military fiction (complete with footnotes explaining technical terms). As an artist, despite having the cats stand on two legs, the rabbits pull triggers, and the various animals share similar sizes, he manages to keep the visuals relatively naturalistic…

Cat Shit One #1

Cat Shit One #1

(I haven’t read the sequel, Cat Shit One ’80, but apparently it follows the bunnies’ special forces – and other animals – into conflicts from the 1980s, including the Soviet war in Afghanistan…)

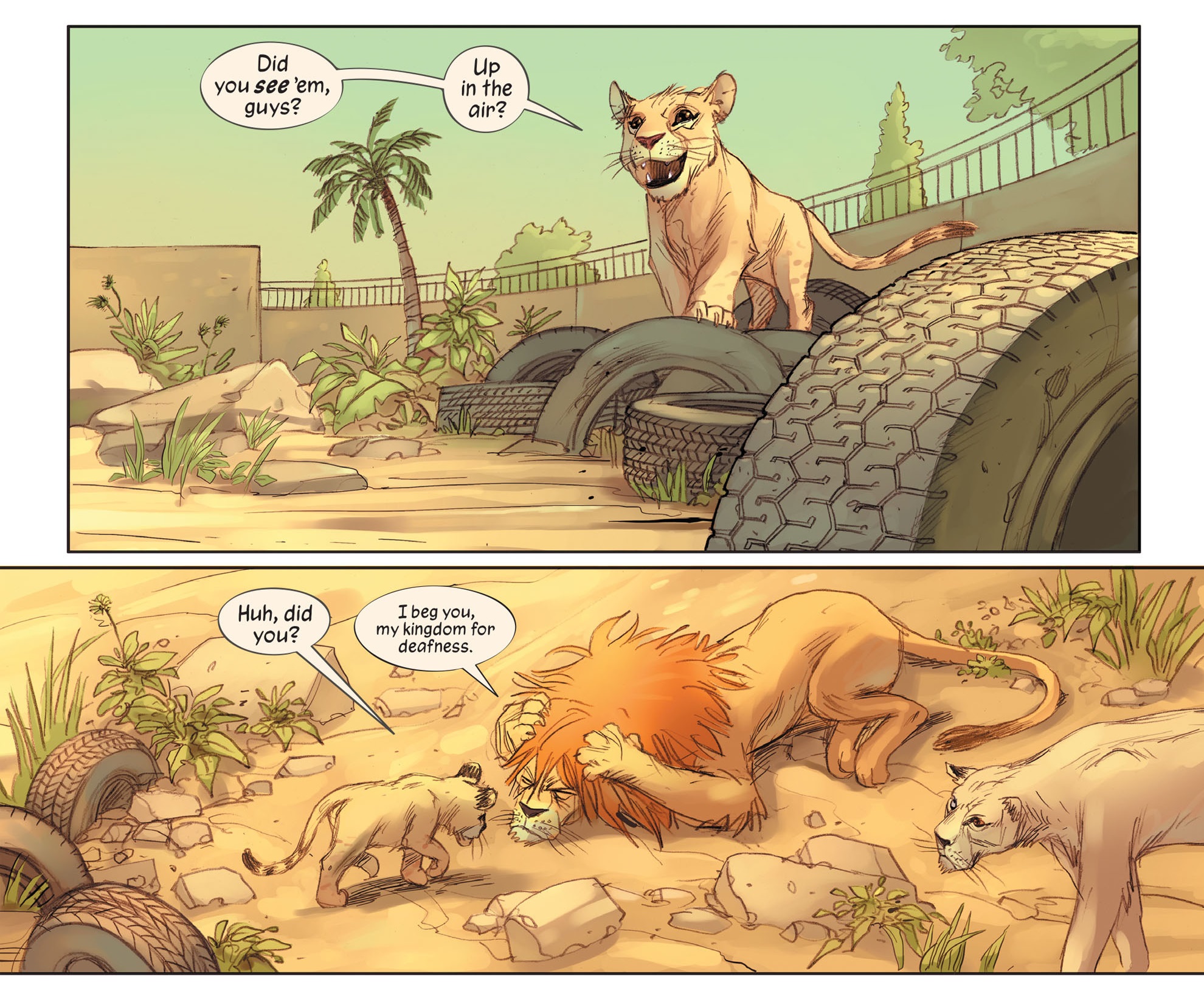

The thing is, of course, that neither Maus nor Cat Shit One actually treat their cast as animals. Whether more or less anthropomorphic in design, the animal features merely serve as icons that correspond to people’s different ethnicities and nationalities, thus addressing a fully human perspective and experience. By contrast, more recently, Brian K. Vaughan took a slightly different route: he perceptively saw in a news story about starving lions who had escaped from the Baghdad Zoo during the American bombing of Iraq, in April of 2003, the potential for an Animal Farm-like allegorical fable about Iraq’s brutal conflation of liberation (from Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical regime) and military invasion (by the United States and a few allies, based on false evidence).

Vaughan has always had a knack for neat – if blatant – symbolism, often culminating in touching endings, as seen in the likes of Y-The Last Man, Paper Girls, The Escapists, and the first volume of Runaways (in turn, Ex Machina finishes with a dark punchline). In the 2006 graphic novel Pride of Baghdad, he gets really carried away, as practically every single sentence and situation has some kind of double meaning.

Pride of Baghdad

Pride of Baghdad

Like the best allegories, Pride of Baghdad does work on multiple levels. The animals are obvious stand-ins for specific elements of Iraqi society, but their tale can likewise be read as a more general parable about freedom, self-determination, and foreign intervention. You can even engage with the lions as individual characters and focus on their personal drama amidst the larger warfare – an approach that’s helped by the fact that Niko Henrichon draws each animal’s body and gestures with physiognomic accuracy, creating a curious contrast with BKV’s writing style (which gives them a human personality, albeit informed by their species’ traits).

Pride of Baghdad was hardly alone in mixing animals with war in the 21st century. Whether informed by growing social consciousness about animal issues or just seeking to take advantage of new storytelling techniques, the last couple of decades have been particularly prolific in this regard. I will be discussing some of the most remarkable works next week!