If you read last week’s post, you know I’ve been discussing war comics that prominently feature animals.

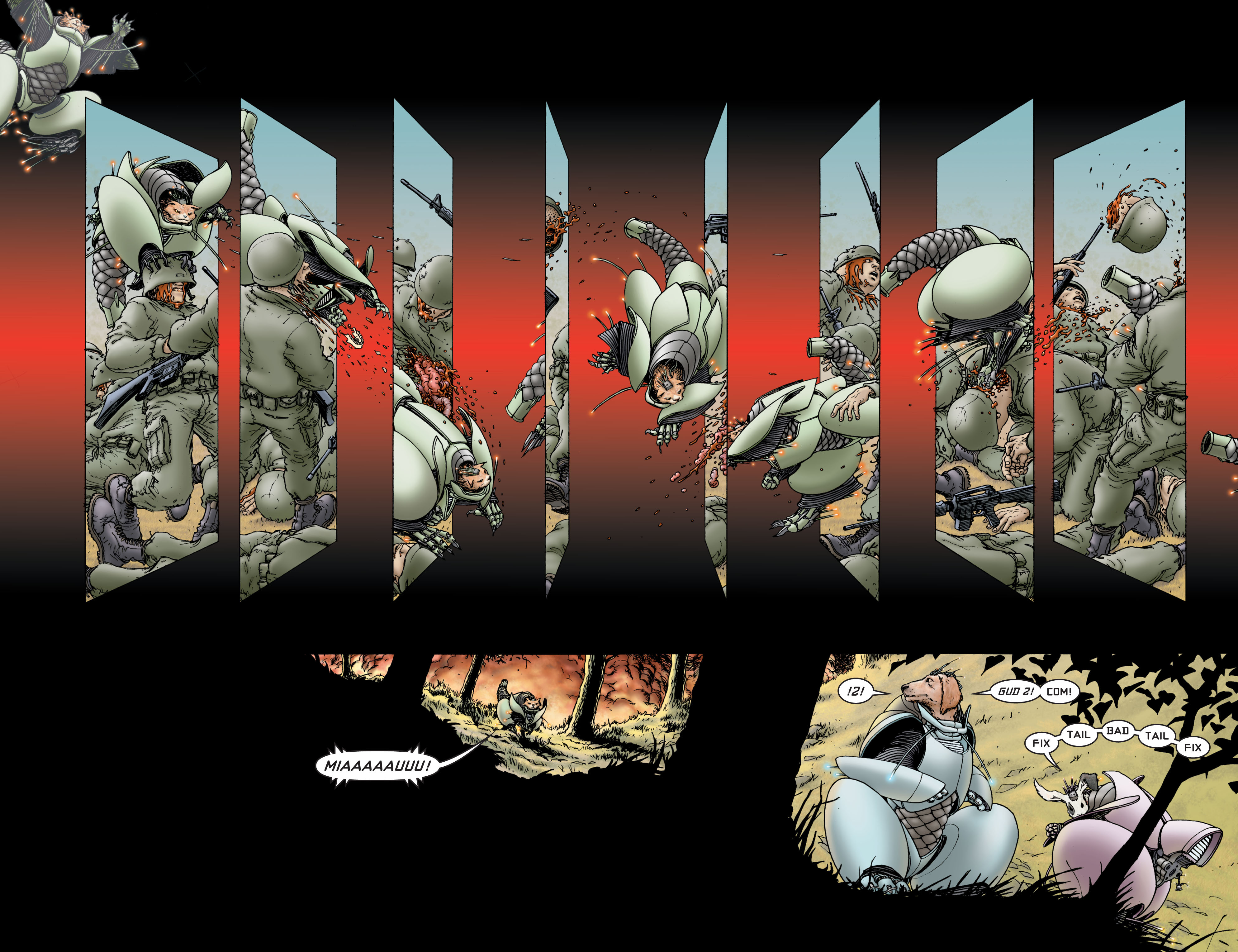

This week, let’s start by looking at 2004’s science-gone-wrong mini-series We3, about a trio of weaponized animal cyborgs (a dog, a cat, and a rabbit) on the run from their military masters. Here is a project that was clearly written not just as a vehicle to touch upon themes that are close to Grant Morrison’s heart (animal rights, callous capitalism, post-human technology), but also as an experiment in pushing the language of comics… or at least in showcasing the kind of mindboggling stuff Frank Quitely can draw when given enough space and freedom.

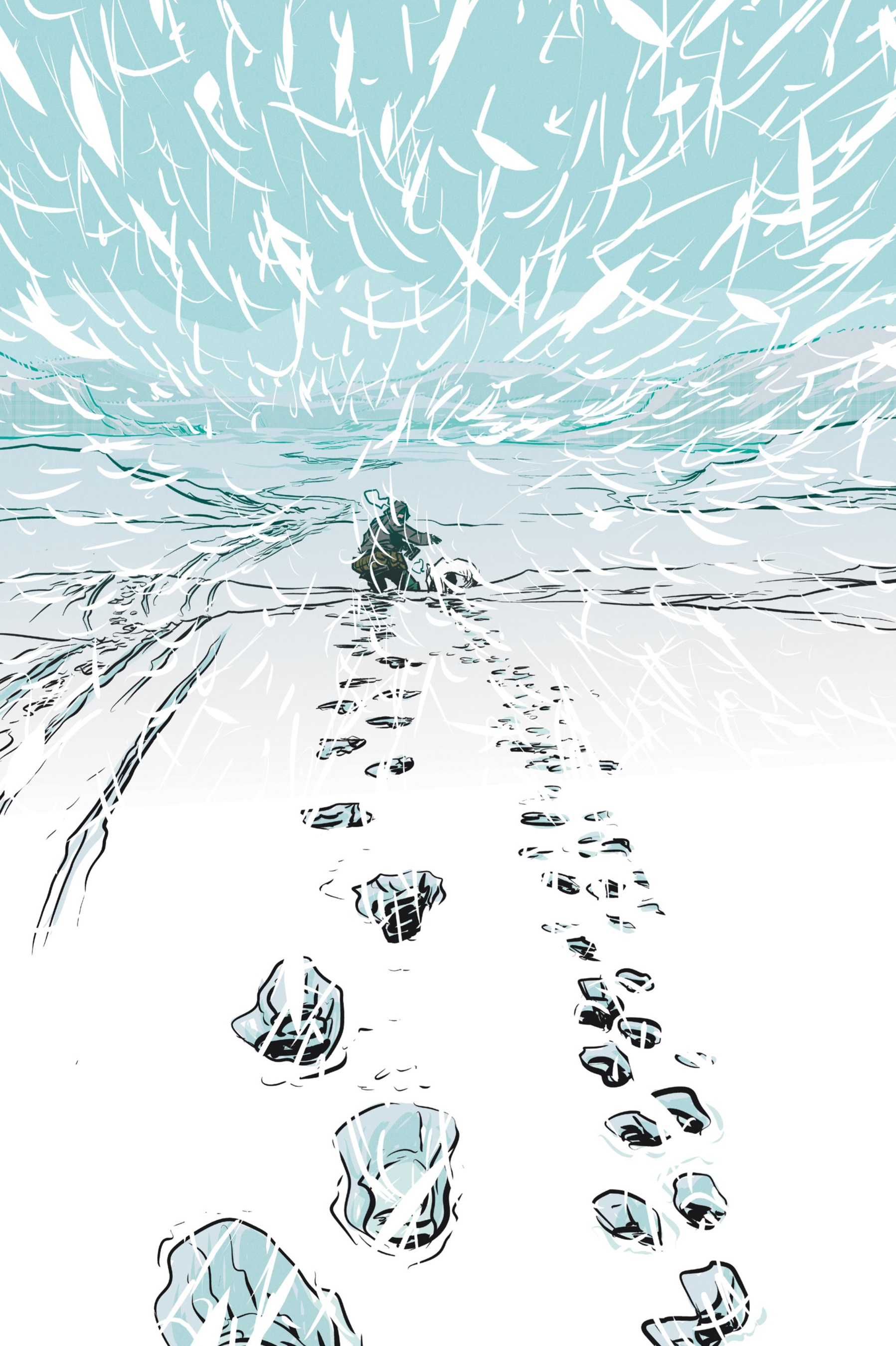

We3 #2

We3 #2

The dialogue is pretty sparse and, although there is a satirical edge to the sci-fi, We3 doesn’t devolve into preaching. Instead, the riveting hyper-violent action is front and center, as Frank Quitely reworks manga techniques to break down time and movement, creating an intense reading experience that still feels fresh after all these years. Along with Quitely, inker/colorist Jamie Grant gives every image an impressive shine (while slickly stressing the contrast between the organic world and the coldness of metal) and Todd Klein once again proves he’s by far one of the best letterers in the business, evoking a range of tones through different fonts. As a result, between the deceptively simple story and the flashy artwork, We3 manages to strike an emotional chord, giving its animals a distinct personality, dignity, and resonant feelings without going the easy route of fully anthropomorphizing them.

We3 became such a modern classic that it was bound to inspire successors. Some of these are quite impressive in their own right…

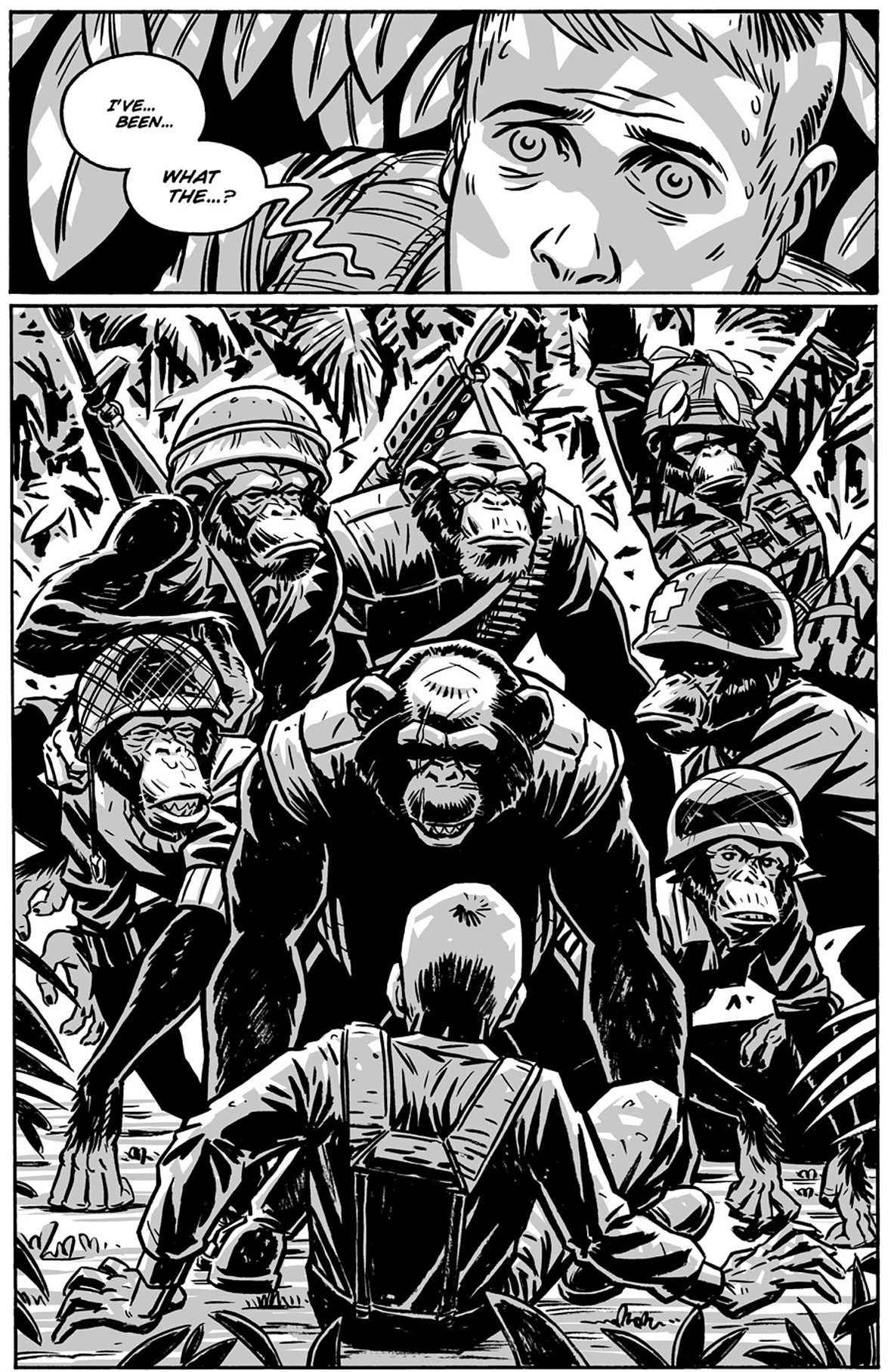

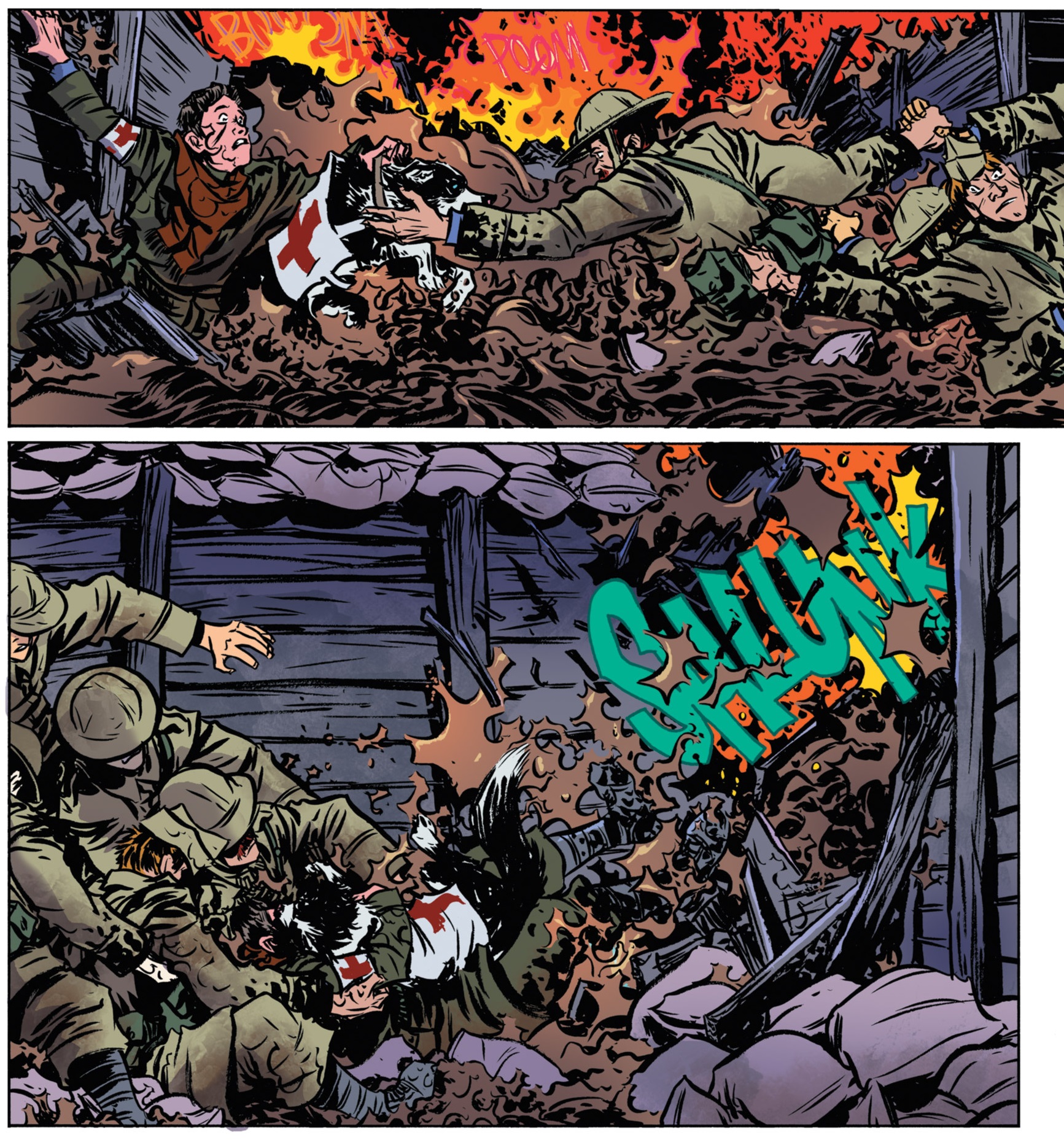

Guerillas #1

Guerillas #1

Set deep in the Vietnamese bush, in 1970, Guerillas follows Private John Clayton as he runs into a rogue platoon of genetically-enhanced chimpanzees who fight with the same guerrilla tactics as the US enemies. Like in Cat Shit One, there is an alluring strangeness in watching one of the most visualized – and therefore recognizable – wars in modern history being reimagined with uniformed animals… However, rather than merely replacing human soldiers with animal versions in some kind of alternate reality, Guerillas adds its primates to a realistic depiction of the conflict, managing to excel both as a harrowing – if often humorous – indictment of the Vietnam War and as one hell of an adventure yarn. Brahm Revel draws incredibly kinetic combat scenes in a Kurtzman-esque style (albeit progressively scratchier) that anticipate – and rival – much of the imagery of War for the Planet of the Apes while also developing a quirky cast that you actually come to care about. Despite Clayton’s recurring narration, many of the panels are wordless (or merely onomatopoeic), so the visuals do a lot of heavy lifting, which Revel pulls off with aplomb.

Guerillas’ first mini-series, which came out in 2008, already hit the ground running. Although reveling in the pulp appeal of chain-smoking chimps with machine guns kicking ass, the comic was quick to establish in-your-face central metaphors: ‘man must become animal to wage war,’ the vicious conflict in Vietnam made us ‘embrace our primal past’ in the jungle, soldiers were ultimately treated as ‘trained monkeys.’ The subsequent volumes invested more in the characterization of both simians and humans… well, at least of the American soldiers and of a couple of German scientists, since for the most part the Vietnamese remained little more than cannon fodder (in this regard, Guerillas isn’t more egregious than most of its peers in the genre, although it’s disheartening that US creators still find it easier to imagine a baboon’s personality over that of a communist).

As far as recent comics go, though, animals in combat aren’t merely the stuff of science fiction. A couple of graphic novels have addressed the real history of how animals have been used for military purposes. The first of these was 2013’s Dogs of War, which features three separate tales of canine feats in conflicts across the 20th century…

Dogs of War

Dogs of War

On the surface, Dogs of War may seem like a throwback to those Lassie-like strips I mentioned at the beginning of last week’s post, but Nathan Fox’s expressionist artwork pushes the material to a whole other level, creating images that are pure comic book magic (as you can see in the scan above). Crucially, Fox gets to shine because writer Sheila Keenan sets each story in a markedly different landscape, namely the muddy Ypres trenches of World War I, a snowy base in Greenland during World War II, and the humid-looking terrain of 1968 North Carolina and Vietnam.

Although getting mileage out of readers’ presumed sympathy for dogs, curiously the book isn’t as dog-centric as the title suggests. In fact, the whole thing has a committedly humanist sensibility. Take, for instance, the first tale, which nominally stars a Red Cross rescue dog called Boots. That tale does a striking job of rendering the sense of pointlessness, claustrophobia, and overall (physical and psychological) dirt associated with WWI: Keenan’s dialogue is packed with gallows humor and Fox’s splash pages touchingly capture the vastness of the corpse-filled ditches and No Man’s Land. Yet Boots isn’t much of a central piece or a POV character – the book is much more interested in the diverse ways the men deal with the extremely harsh conditions around them. If anything, Boot’s seemingly well-adjusted attitude and moral purity serves as a contrast to the pervasive atmosphere of doom… on top of providing a comic relief:

Dogs of War

Dogs of War

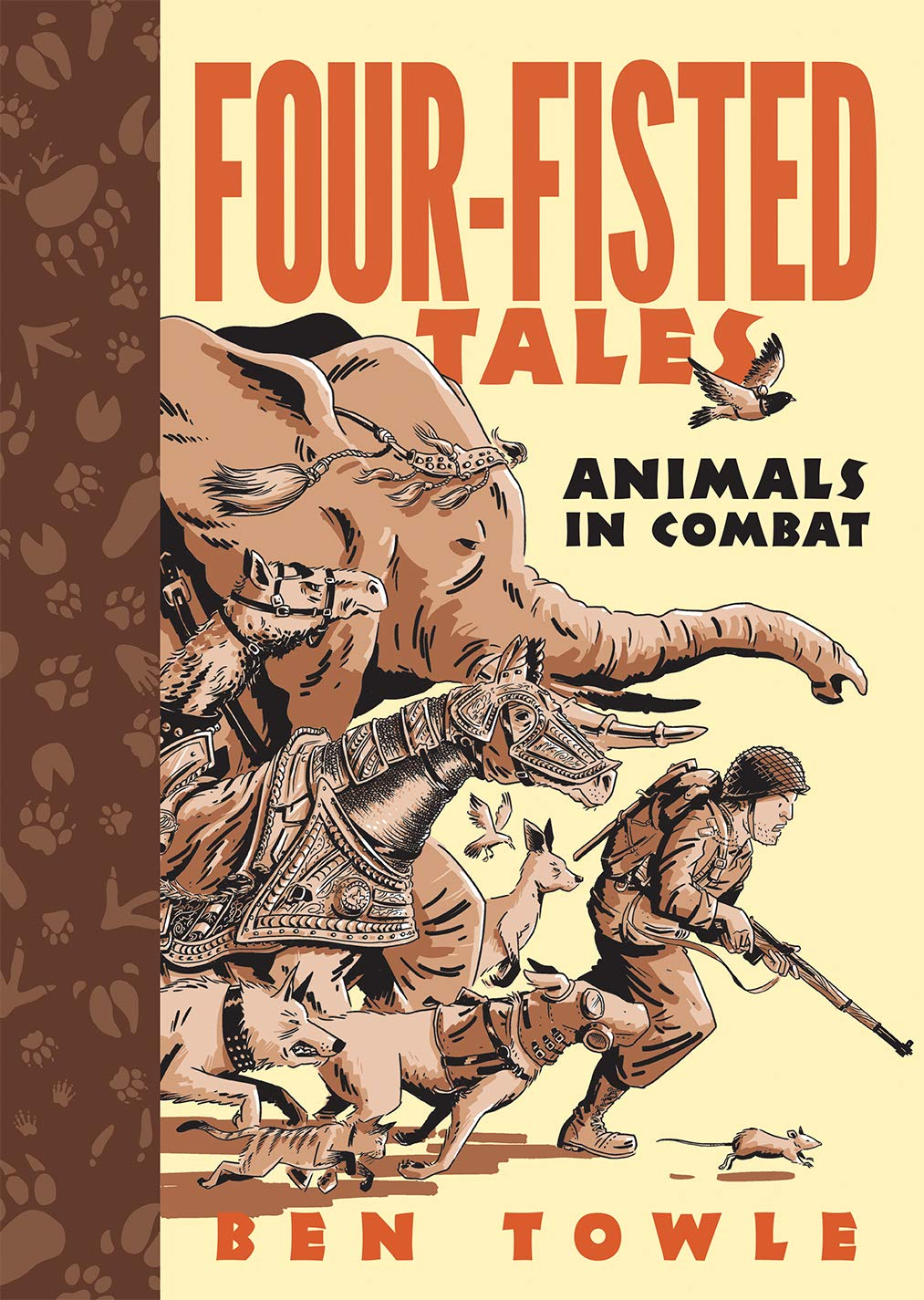

All this brings us to 2021’s Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat, a nifty, fascinating graphic novel written and illustrated by Ben Towle, who truly expanded my understanding of the functions animals have served in war. For one thing, the book doesn’t stick to American armies or to conflicts of the 20th and 21st centuries. Oscillating between descriptive non-fiction and short period pieces (they’re essentially vignettes), Towle goes back to Ancient Rome, to Genghis Khan’s mounted cavalry, and to the Battle of Trafalgar while also engaging with South African, Polish, and Castilian forces, among many, many others. And sure, we get more comics about dog soldiers (in the US Civil War and in WWI), but Four-Fisted Tales is also highly diverse in terms of all the species it covers, ranging from horses and bears to seagulls and slugs…

The book rarely takes an openly moralistic stance on war or on animal abuse, treating most episodes with a certain matter-of-factness that – in theory – leaves it up to readers to judge things for themselves. Because the focus is more on the victors, the result does implicitly justify the use of animals in battle, but the provocative opening quote (and the accompanying image) nudges readers to take into account that these aren’t stories about military courage or sense of duty or any other ideal, since the animals never made a conscious choice to participate in the conflicts anyway.

While this subtext is there if you look for it, on the surface Ben Towle doesn’t seem all that keen to editorialize or directly problematize the implications of enrolling these creatures in the fighting process. Rather, he digs up plenty of curious, lesser-known instances of armed forces deploying animals’ strength, instincts, and/or unquestioning obedience, which you can read either as exposing the sad exploitation of nature in the service of human-driven violence or as an inspiring celebration of animals’ value in people’s lives and of their decisive importance in major historical events (not to mention an ode to the military’s resourcefulness in the field).

Likewise, Towle isn’t interested in allegories or in speculative fiction, but in the fantastic stuff that actually happened. The most obvious comparison in terms of comics, then, would be Dogs of War, although Towle’s writing lacks the dramatic punch and relatively nuanced psychology of Sheila Keenan’s scripts, which are more ambitious on the emotional front, even if they have a much less informative scope (curiously, though, Dogs of War has a useful ‘Further Readings’ section, while Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat lacks any bibliography).

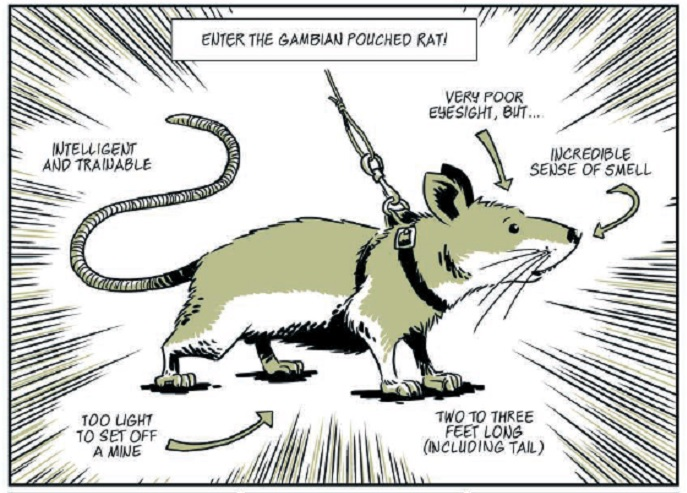

That said, Towle excels not just as a researcher, but also as an artist, using the medium of comics to vividly – and synthetically – communicate the actions and features of creatures in radically different contexts, like in this panel about mine-detecting rats:

Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat

Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat

I love how Ben Towle explores the medium’s possibilities as he keeps trying out new formats throughout the book. Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat opens with straightforward narratives, shifts to text-heavy illustrated entries, and later switches back and forth between variations of these two approaches, including a particularly action-packed WWI story in the middle. Between this and the fact that Towle’s designs owe a clear debt to Harvey Kurtzman and Jack Davis, the title ends up being more than a playful pun, fully justifying the intertextual nod – the result feels like a modern, animal-themed special issue of EC’s classic anthology Two-Fisted Tales!

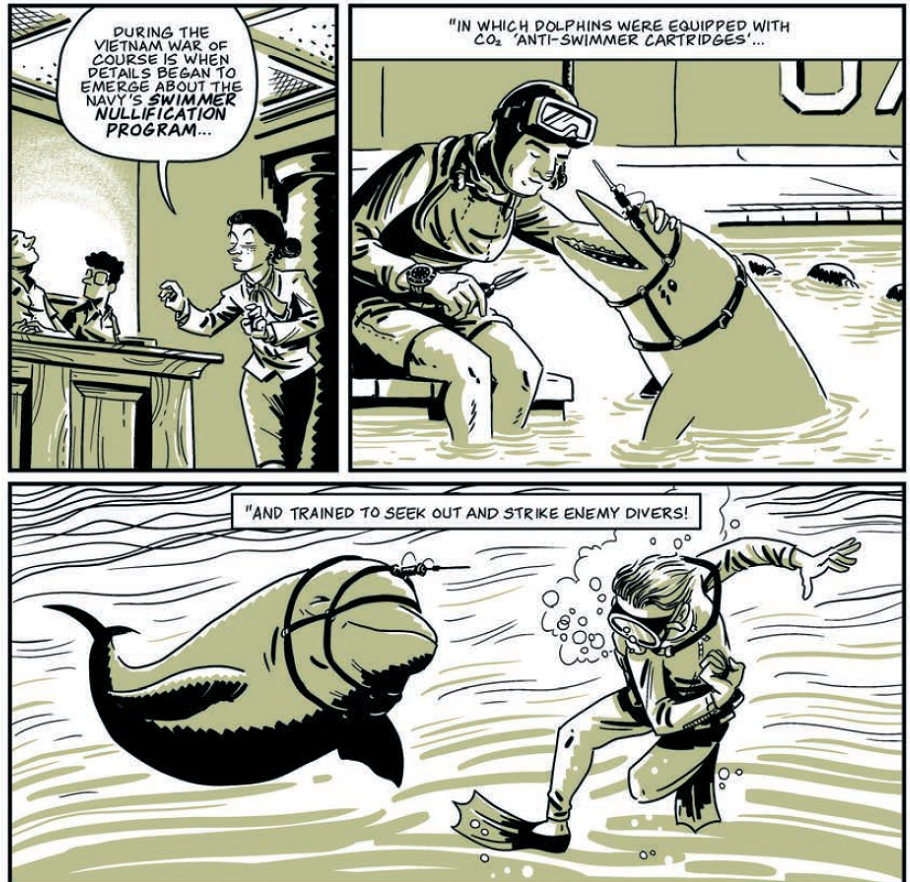

High points include a finely-crafted tale that follows parallel storylines set in the Vietnamese jungles of the 1960s and 2010s (drawn with contrasting thickness of line and shade, to great effect) as well as one that is framed by a court trial over military programs involving sea mammals. A tale in Iran is essentially ‘silent.’ A piece about carrier pigeons is told mostly through gloriously detailed splash pages.

At the same time, there is a visual coherence ensured by Towle’s smooth cartooning and by the minimalistic olive green/grey palette, which also help keep the book surprisingly light – and even fun – given the disturbing, depressing, and gory subject matter. Indeed, like Dogs of War, this can be safely shelved in a library’s YA section, confirming once again that many of the most visually engaging comics out there aren’t aimed exclusively at adult audiences, regardless of genre (having recently come across Luke Pearson’s kids-geared comedic fantasy series Hilda, I was likewise blown away by its action scenes).

Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat

Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat

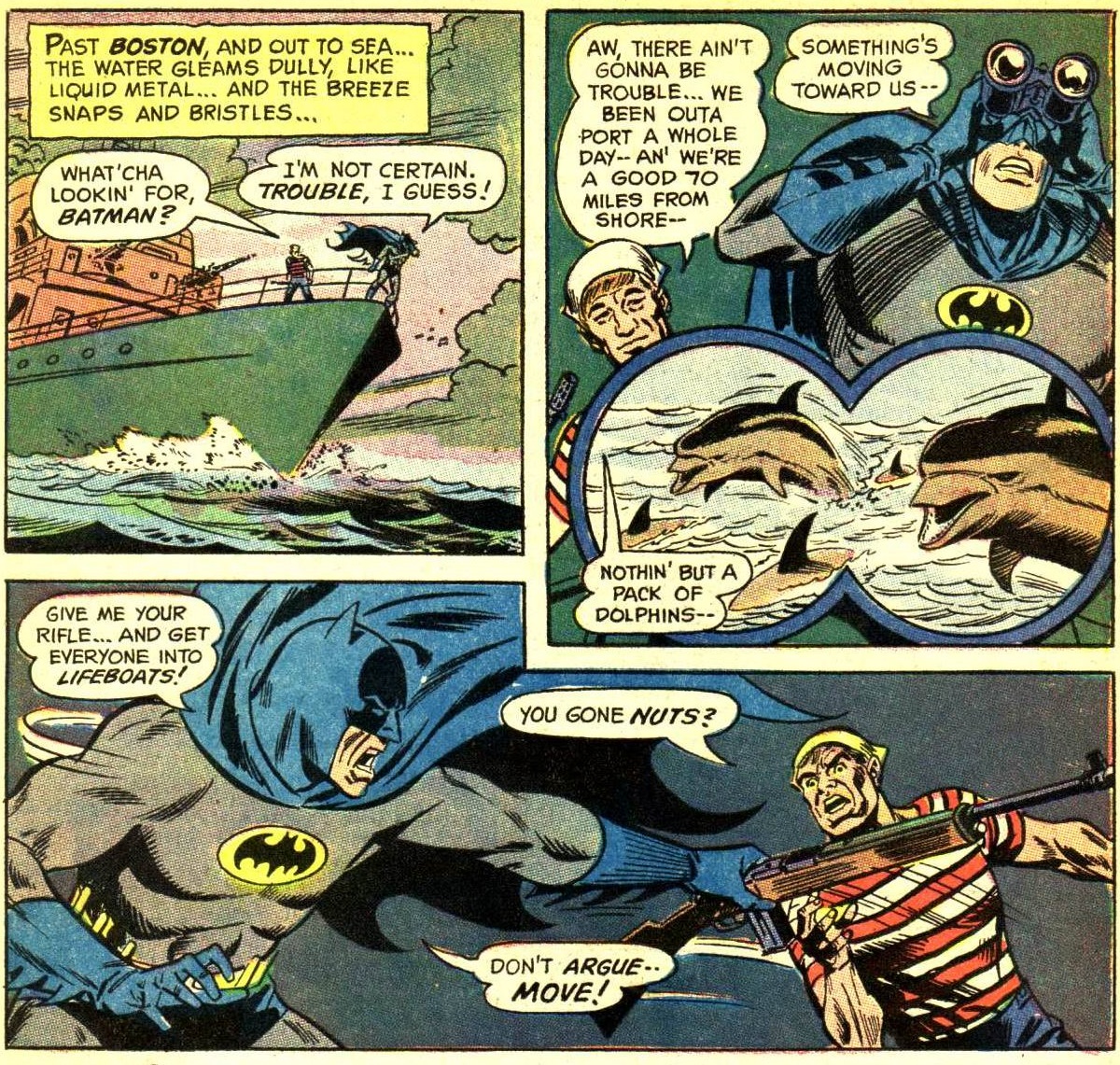

I know what you’re thinking and, yes, I totally agree, the Vietnam War’s swimmer nullification program does help explain Batman’s paranoia about dolphin assassins during this period: