The main reason The Ludocrats was Gotham Calling’s 2020 Book of the Year is that, by the time I did the list, I hadn’t yet read Portrait of a Drunk (a nihilistic piece of ribaldry that lives up to Seinfeld’s motto: ‘no hugging, no learning’). Yet it was also because The Ludocrats was a consistently hilarious book that kept surprising me at every turn. This was elevated by the fact that the series verged increasingly into metafiction towards the end, playing both with the medium’s form and with different narrative traditions in original, entertaining ways.

I was hoping for something similar when I picked up the latest reboot of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt, also written by Kieron Gillen… but boy did I get much more than that!

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #5

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #5

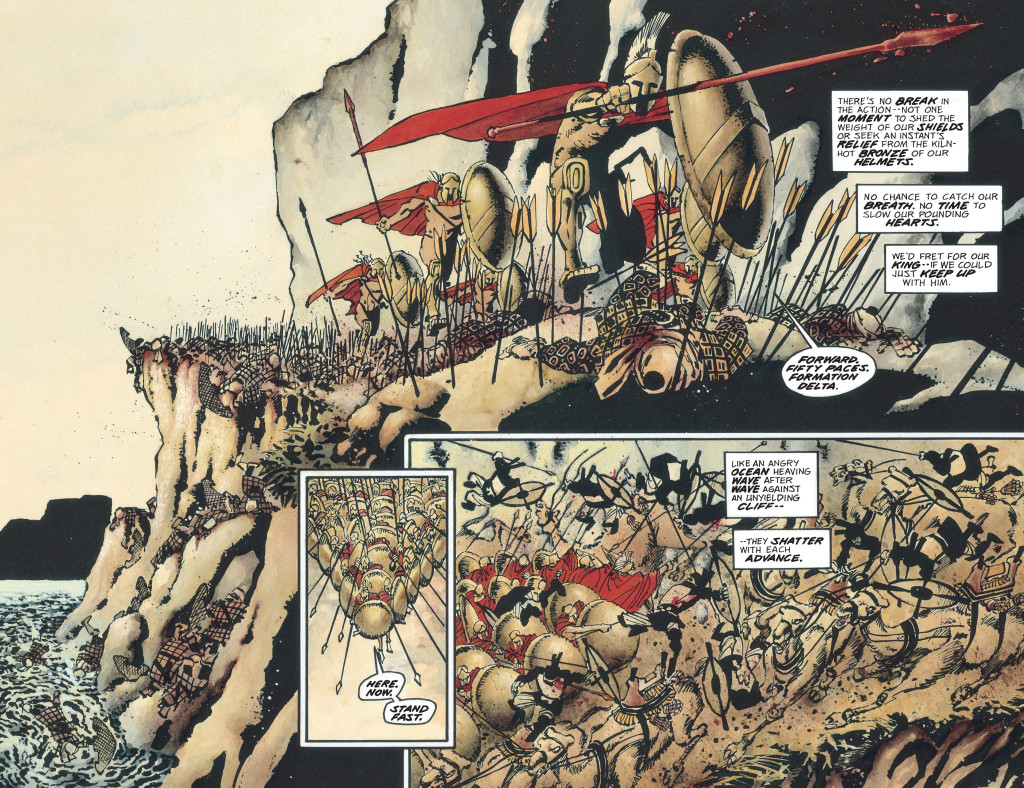

Some context. Besides The Ludocrats, Kieron Gillen has a long history of engaging in intertextual dialogue with other comics, including with giants of the field. Notably, his 2014 mini-series Three was a response to 300, Frank Miller’s and Lynn Varley’s proto-fascist epic about the Battle of Thermopylae, where three hundred Spartan warriors supposedly held their own for days against Persian invaders that massively outnumbered them. Whereas Miller – through his signature breathtaking visuals and hardboiled dialogue – emphasized the Spartans’ bravery and stamina, Gillen focused on their slave system, telling the story of three helots who held their own against three hundred Spartans (effectively reversing the position of the previous heroes by privileging compassion and class solidarity over manly stoicism and nationalism).

Three is a witty, exciting yarn in its own right, developing characters you come to care about (in contrast to 300’s superficial cast). The polemic with Miller stays relatively indirect, even if King Leonidas’ most quoted line (‘Ready your breakfast. And eat hearty – for tonight we dine in Hell!’) does get subverted at one point (‘So come, any who would dine in Hades… Let those who lived there show you the way.’) and even if the climax at the ravine brings to mind 300’s opening tale about the wolf. Likewise, Ryan Kelly’s artwork and Jordie Bellaire’s colors secure the series’ own identity, despite occasional echoes of Miller’s and Varley’s aesthetics:

300 #4

300 #4

Three #5

Three #5

If there is one property that lends itself to similar revisionist gestures is Thunderbolt. Originally created by Pete Morisi for Charlton back in 1966 and, later, part of the DCU for a while, Peter Cannon is a white, blonde American (an orphan, as per tradition) raised in a Himalayan lamasery, where he attained peak mental and physical perfection and, as ‘the chosen one,’ was entrusted with the knowledge and wisdom of mystical ancient scrolls, on top of developing kickass martial arts’ skills. Yep, Cannon – along with his confidant, Tabu Singh – embodies several problematic tropes of a certain branch of orientalist fiction, with a touch of eugenics, like a not-so-distant cousin of Doc Savage and Iron Fist (hell, even Batman!).

That said, when Thunderbolt got a reboot at Dynamite, in 2012, writers Steve Darnall and Alex Ross did not mess with any of this stuff (except for one twist I refuse to spoil), approaching it with a straight face and hardly a wink. Not only that, but artist Jonathan Lau rendered the visuals in a classic, if elegant, style, privileging clear, dynamic storytelling of the widescreen variety so common in 21st-century superhero comics. The same mainstream attitude was adopted by colorist Vinicius Andrade and letterer Simon Bowland. The result was a breezy – yet ultimately uninspired – 10-issue run, pitting Peter Cannon against Obama-era villains such as the owner of a FOX News-like network and a hawkish general committed to American exceptionalism. This largely forgettable series has been collected in an omnibus whose most remarkable feature is a previously unpublished Morisi story (which the veteran creator did for DC’s Secret Origins, back in 1988).

Still, at least the action was pretty slick:

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v2) #2

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v2) #2

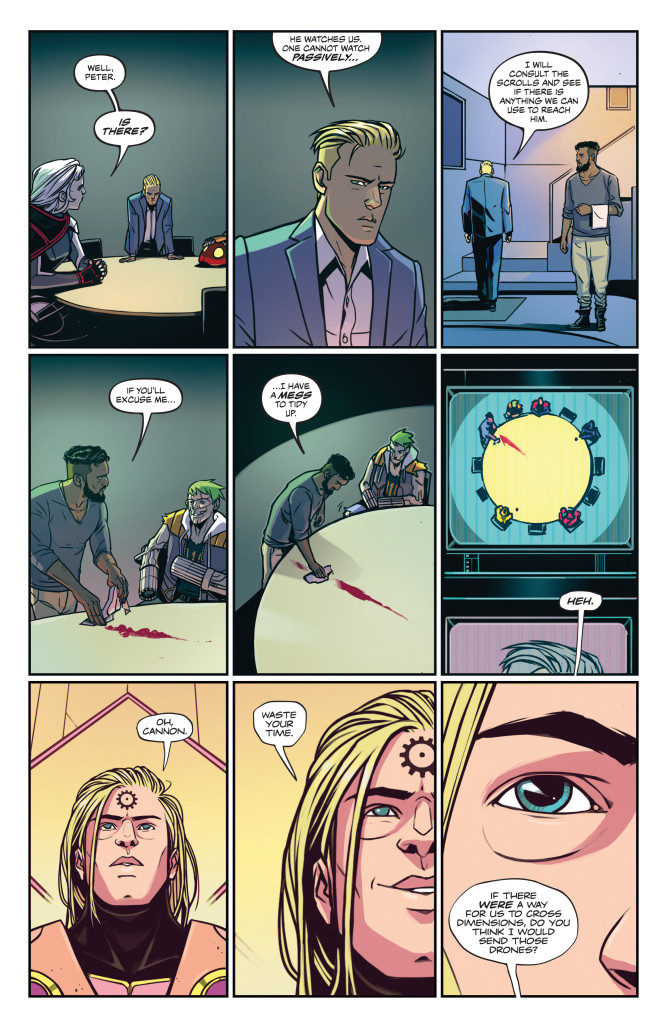

In 2019, when Kieron Gillen – working with artist Caspar Wijngaard, colorist Mary Safro, and letterer Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou – had a stab at the property, I knew he was bound to bring a higher degree of awareness to this material. If nothing else, I expected him to engage more cleverly with the fact that Thunderbolt had been famously recast as Watchmen’s Ozymandias (there was a nod to this in the previous reboot, but it was as bland as everything else…).

And, sure enough, the connection to Watchmen was there from the get-go. The intro situated the story ’35 minutes into the future,’ in a clear allusion to Ozymandias’ classic line. There were callbacks to other fan-favorite passages and several in-your-face puns, visual and otherwise (‘To watch changes everything.’). The comic also referenced key post-Watchmen superhero texts, such as The Ultimates and Animal Man, not to mention Zack Snyder’s film adaptation (‘How did the cool one in that shit movie put it?’).

The shocking thing that soon became apparent, though, was that this Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt mini-series (collected in a volume suitably called Watch) wasn’t just paying homage to Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’ opus and their impact in the field… It turned out to be a stealth sequel!

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #2

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #2

That’s right, in the same year that HBO released Damon Lindelof’s acclaimed show and DC finished publishing Geoff John’s and Gary Frank’s infamous Doomsday Clock comic, there was a third series providing yet another alternative future for Watchmen’s cast and concepts. (There are many reasons to explain this confluence, but one of them is probably generational: Lindelof, Johns, and Gillen, who are all roughly the same age, must’ve been impressionable teens at the height of Watchmen’s influence, in the late 1980s. They’re now in their mid-40s, at a stage in their careers where they can get the free rein to settle old scores.)

Like the other two sequels (and like DC’s flood of lame prequels and spin-offs in the past decade), Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt establishes its credentials through visual continuity, namely – as you can see above – by revisiting the original’s memorable nine-panel grid as well as the iconic sliced circle motif… Some quotations are even more direct. I’m guessing most readers probably recognized the scan at the top of this post as Wijngaard’s take on Watchmen’s first title page:

Watchmen #1

Watchmen #1

While I haven’t much sympathy for DC’s/Warner’s attempts to shamelessly milk Watchmen’s cow – not least because I believe much of the original’s power derives from its self-contained format – I’m willing to open an exception for a smart, playful project published by a smaller company that daringly puts its own spin on this decades-old masterpiece, delivering a thinly-veiled follow-up while poking fun at the evolution of superhero fiction since 1986. (It’s the kind of iconoclastic move Moore himself excelled at in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.)

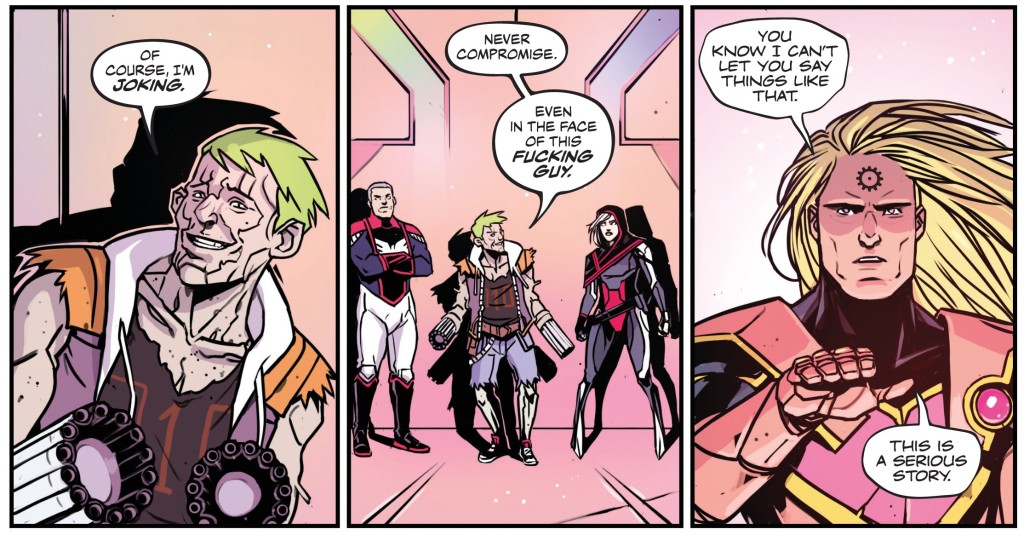

Still, there can be too much of a good thing. Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt is slavishly packed with allusions to all of Watchmen’s greatest hits, from ‘a raft of corpses’ to Rorschach’s finger-breaking torture. The meta-commentary devolves into full-blown lecturing, with characters given awkward, on-the-nose dialogue such as ‘I have transcended your genre.’ or ‘This is not magic. This is… formalism.’ It doesn’t help that the series’ perspective on Watchmen comes across as quite narrow-minded (as if the original had been a purely deconstructive, prescriptive, soulless, humorless work) and the satire of the ensuing wave of simplistic, violent imitators isn’t particularly insightful or groundbreaking either… (You can find a funnier take on these ideas in Warren Ellis’ StormWatch and a more provocative one in Grant Morrison’s The Multiversity.)

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #2

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #2

If you think Watchmen lacks subtlety, wait until you get a load of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt, where Gillen seems damn set on making sure you get what he is doing. Even a neat riff on the notorious bit from The Ultimates where Captain America points to the symbol on his helmet is spoiled by showing up a second time, in a more obvious guise (plus, again, Ellis’ version made me laugh louder).

One of Moore’s and Gibbons’ major accomplishments in the original was the way they managed to weave multiple layers of metafiction and political themes *without* letting them fully take over the comic – at a primary level, you can disregard the subtext and still be left with a satisfying narrative… Hell, much more than satisfying: it’s riveting and genuinely involving and dramatically powerful and, yes, often drenched in dark comedy (not just ‘a serious story’). In turn, Thunderbolt is playing a whole other game, one where the narrative has, above all, an ancillary role as a gateway for a highly conceptual reflection, eventually leading into downright pastiche…

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #4

Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt (v3) #4

I usually have a lot of time for meta-comics (I loved Gillen’s choose-your-own-adventure tale in Batman: Black & White a couple of months ago) and there are sure plenty of fun moments in Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt – not to mention the fact that Wijngaard’s and Safro’s collaboration makes every single page a delight to look at! For the most part, though, the result is something I appreciated more than giddily enjoyed, nodding with interest and recognition more often than actually smiling (a similar feel to watching the first episodes of WandaVision, before the story took off).

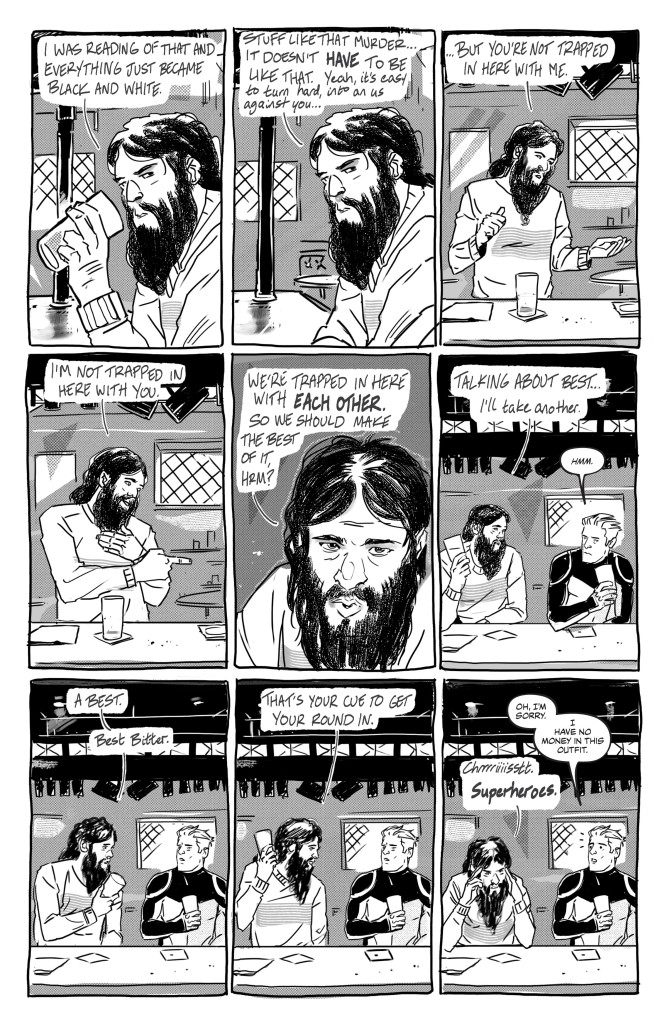

Pages like the one above make me feel like a decoding machine. I see the color-based wordplay, the twist on Rorschach’s badass line about prison, the way Caspar Wijngaard draws the character to look like Alan Moore, and the general evocation (helped by Otsmane-Elhaou’s letters) of slice-of-life indie comics, particularly of Eddie Campbell’s Alec. And yes, I realize the double meaning of this choice, since Campbell went on to work on From Hell, which is also a key post-Watchmen text, signaling Moore’s search for further realism and (temporary) commitment to pushing the medium beyond superheroes after having taken that genre to an extreme…

From Hell

From Hell

I respect that the goals and approach behind Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt were different than those of Watchmen, but I cannot help finding it ironic that this new series ends up doing exactly what it (unfairly) attributes to the original: it comes off as an essentially formalistic exercise trapped in the confines of its own tight design. Sure, the closing lines, sealing the take-away message, do hint at a larger statement about humanity, but those aspects seem somewhat forced, as if they’re just part of the comic’s mechanical structure. Even the hero’s character arc feels like little more than a rhyme with Dr. Manhattan’s (as opposed to Three‘s deeper emotional payoff, for instance).

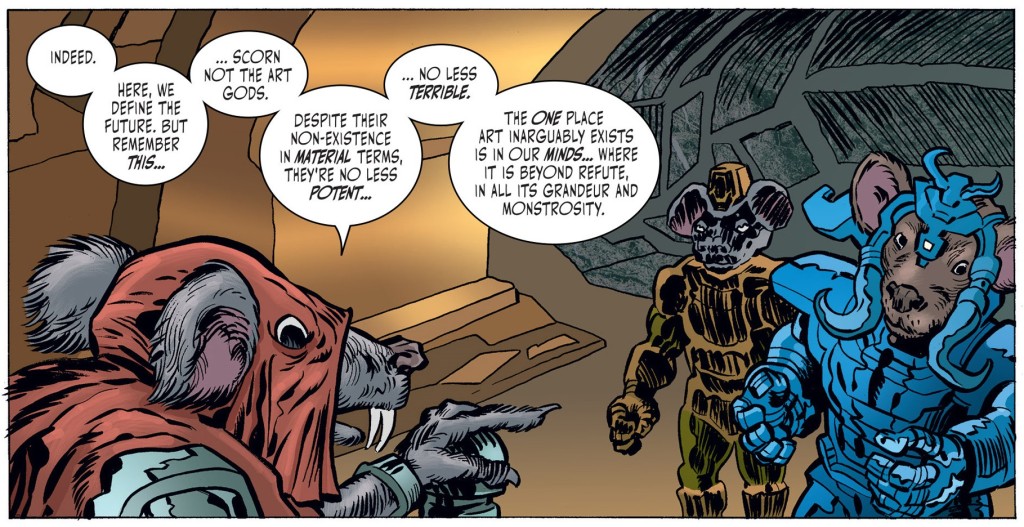

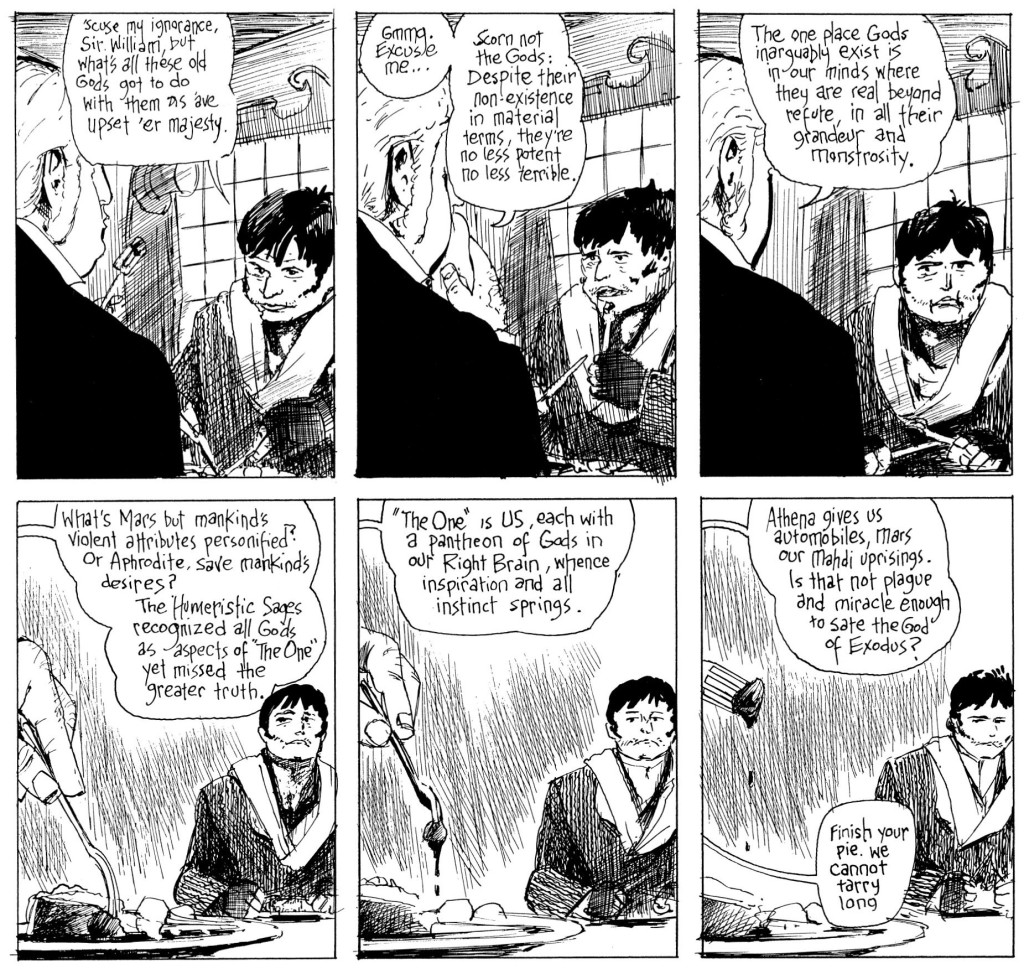

By this stage, did we really need another explicit reminder that superhero comics should get out of Watchmen’s shadow and try to forge new paths? If we have to keep going back to Alan Moore, then let’s at least find other stuff to reappropriate and cooler ways to do it. For example, when exploring notions of art and divinity in Gødland, Joe Casey and Tom Scioli chose to recontextualize the passage above, from Moore’s and Campbell’s historical graphic novel about Jack the Ripper… in a scene featuring mutant super-mice: