Last time I did one of these ‘Catching up with crime comics’ posts was a year ago, back in November 2022, looking specifically at Texas-set yarns (in the meantime, I’ve finally read Ethan Hawke’s and Greg Ruth’s Meadowlark, a superb-looking graphic novel that does a fine job of developing an emotional father-son dynamic among the genre thrills…). This time around, I’m focusing on more-or-less recent works written by Ed Brubaker. After all, having discussed his hit-and-miss work on Batman, I figured it’d be fair to also devote some of the blog’s attention to Brubaker’s field of expertise: no-holds-barred crime comics!

Ed Brubaker’s greatest opus continues to be Criminal, the irregular series he has been doing with Sean Phillips since 2006, chronicling the gritty dramas of different generations of low-level figures in the criminal underworld of the fictional Center City.

From the outset, Criminal stood out as a series of tense, cleverly plotted yarns about engaging characters that played with readers’ expectations, from the guy who looked soft yet turned out to be holding back violent instincts to the badass on a personal killing spree who ended up compromising when push came to shove. Having recently reread the whole thing, I found it even better than I remembered – and it felt like a much more intimate project. You can find plenty of recurring motifs from Brubaker’s comics, such as substance addiction, voyeurism (especially people seeing somebody they know having sex through windows or cupboards), and a referential attitude, explicitly commenting about movies, music, or books that influenced him (including a geeky, self-reflexive interest in how they were made and how they impact people). Like many of Brubaker’s other collaborations with Phillips, Criminal isn’t merely a case of expertly crafted genre comics – these are also comics *about* genre… and, consciously, about comics.

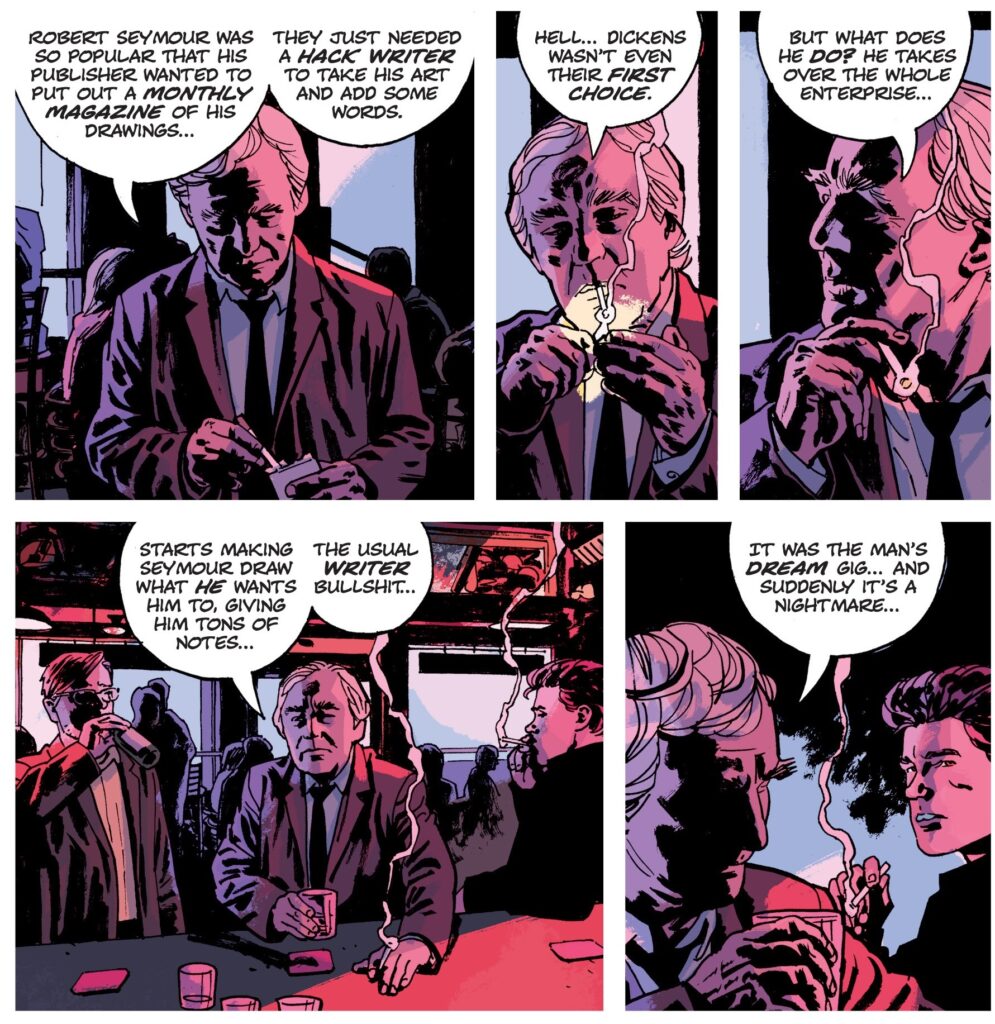

Brubaker’s talent, to a great degree, lies in the way he takes these elements and manages to make them personal and thematically layered through rich characterization (usually in the form of inner monologues). For instance, the two-parter ‘Bad Weekend,’ about a cranky old artist at a comic book convention, could’ve been a fan fest of industry in-jokes, deep cuts, and peeks behind the curtain, either parodying or romanticizing the medium’s milieu and history. And yet, Brubaker somehow finds a pitch-perfect tone that humanizes this odd subculture, acknowledging both that comics are often made in shitty exploitative conditions and that the result can nevertheless have a mesmerizing effect.

Suitably, part of what makes this story work so well is precisely the magic of the art form as conjured by the stylish, chiseled drawings and ultra-moody colors of Sean Phillips and his son, Jacob…

Criminal (v2) #3

Criminal’s latest arc, ‘Cruel Summer,’ came out as single issues in 2019, as a hardback collection in 2020, and, finally, as a softcover a couple of years ago. With its carefully put together mise en scène and smoky palette, this is a brilliant graphic novel (it could’ve been one of Gotham Calling’s 2020 Books of the Year, by I preferred to highlight another notable Brubillips venture, Pulp), spinning one my favorite types of crime narratives, in which the perspective keeps jumping from chapter to chapter (each focusing on a different character than the last), so that instead of a firm center of identification – and morality – you spread your empathy around while being aware of various angles that the individual cast members can’t see. There are echoes of Kubrick’s The Killing, but everyone is so lovingly fleshed out that you can get lost in their dreams and anxieties and sometimes forget you’re in the middle of a concentric tapestry of heists.

In a way, Cruel Summer feels like a culmination of the whole series (it could satisfyingly be the final book, although I’m certainly not complaining about last year’s short ‘Teeg’s Christmas Carol’ in the anthology Image! #9), revealing mysteries that were hinted at in the very first story, paying off character arcs that have been developing for years, and providing the origin of the status quo we found when we initially joined the ride. Yet this is also a taut, self-contained tale that can just as easily be appreciated by newcomers or by those who don’t fully remember past installments… In fact, since the series isn’t chronological (this story takes place in the summer of 1988, both before and after previous stories), this may be as good place as any to jump aboard. It means you’ll know a few secrets when you check out other volumes, but if you had read other volumes before you’d know a few secrets coming into this one anyway… Regardless, such background knowledge doesn’t necessarily work as a spoiler, but more likely it serves as a kind of foreshadowing, since Criminal’s power resides in the specific details.

Or, better yet, much of the power resides in little moments, especially when you get a whiff of hidden aspects of characters’ personalities combined with an awareness of their inexorably tragic fates. I’ve complained before about Ed Brubaker’s flair for overexplaining symbolism and motivations, but I think that in Cruel Summer he generally pulls this off with a pleasant literary sensibility. His beautiful narration suggests just enough for us to get a hint of who these people are, like when he links Jane’s ethics to the context of nuclear panic:

Criminal (v2) #8

The best way to explain it is with a detour about Quentin Tarantino (bear with me). I can often tell where Tarantino’s films are coming from. His sensibility was clearly formed by exploitation movies like Navajo Joe and Black Caesar (especially the perverse racialized killing near the end). The thing is that Tarantino manages to produce moments that deliver the same kind of thrill beyond a mere sense of recognition. There is an element of pastiche, for sure, but it tends to gain extra layers through remix and collage: thus, just as François Truffaut reworked a bunch of Hitchcock set pieces in the awesome, surreal black comedy The Bride Wore Black, Tarantino somehow remade that film as an even more awesome and more surreal black comedy, Kill Bill. There was a panel on Radio versus the Martians years ago that nailed it: trashy flicks from the ‘70s have great moments in them, but also a lot of lame stuff your memory deleted… yet Tarantino has successfully metabolized that age of cinema, drawing on its best ideas to create something that feels, not like the original movies, but like many of us (mis)remember them.

To a large degree, I get that from Criminal, where Ed Brubaker seems to have digested his influences and carefully synthetized them into the best version of what they can be. An early arc, ‘Lawless,’ combines the formulas of revenge and mystery with a classic heist thriller (plus a brief homage to nuns-with-guns schlock). There was a sequel of sorts, ‘The Sinners,’ which boiled down to a detective story within a gangster yarn… and it even included a deadpan riff on The Punisher: Welcome Back, Frank. And the thing is that all of this worked perfectly fine regardless of whether or not you had come across any such material before!

At the same time, as empty as Tarantino’s pop-eats-itself M.O. may seem, I do think there tends to be something there to grapple with underneath the loud surface, as he is one of those auteurs who fascinate me precisely because they keep finding new approaches to their pet themes, much like Peter Milligan or Woody Allen. Milligan has written over a thousand very different stories and practically all of them are about the fluidity of identity in one way or another, up to his latest crime comic, Dogs of London (with a focus on class identity). In Allen’s case, the 21st century has not been kind to him (in terms of either personal reputation or general quality of output), but his proto-noir exercises – like Match Point, Irrational Man, or Coup de chance – are interesting variations on the subject of life’s amoral meaninglessness, just as his dramas – like Blue Jasmine or Wonder Wheel – keep going back to characters whose retaliation for emotional hurt has devastating consequences (read into that what you will).

As for Tarantino, his 21st-century works have explored cinema’s relationship with the notion of cathartic payback in truly original, riveting, and provocative ways. Indeed, as much as I was let down by Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, conceptually I do appreciate that the movie once again pushed revenge fiction to a new level. Rather than merely retread the historical revisionism of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, Tarantino created a whole new sort of retroactive revenge: since the protagonists aren’t driven by a thirst for vengeance (because they have no idea what they’re doing, unlike the previous films’ Jews and slaves) and since there is no diegetic crime to avenge (at least compared to the one we know took place in our own reality), ultimately the revenge fantasy is only in the viewers’ minds, because we’re the only ones who truly know the stakes.

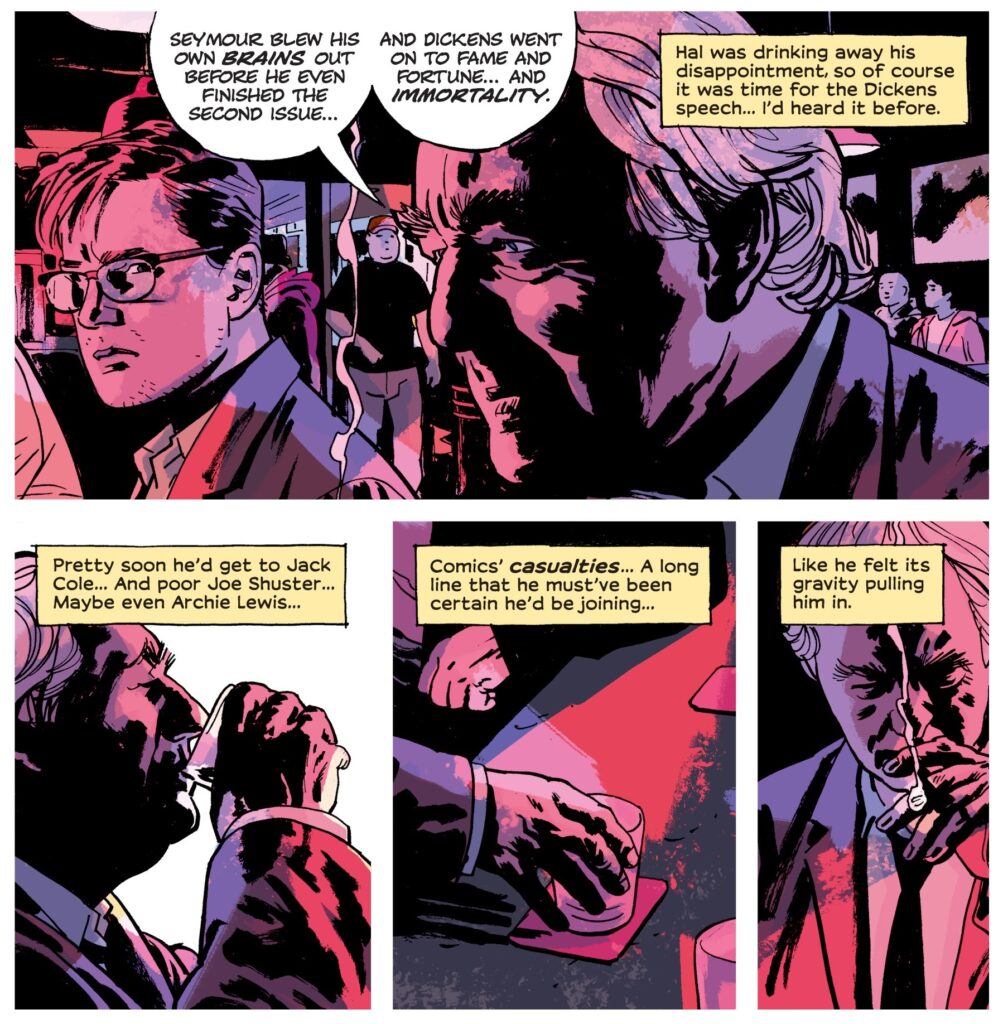

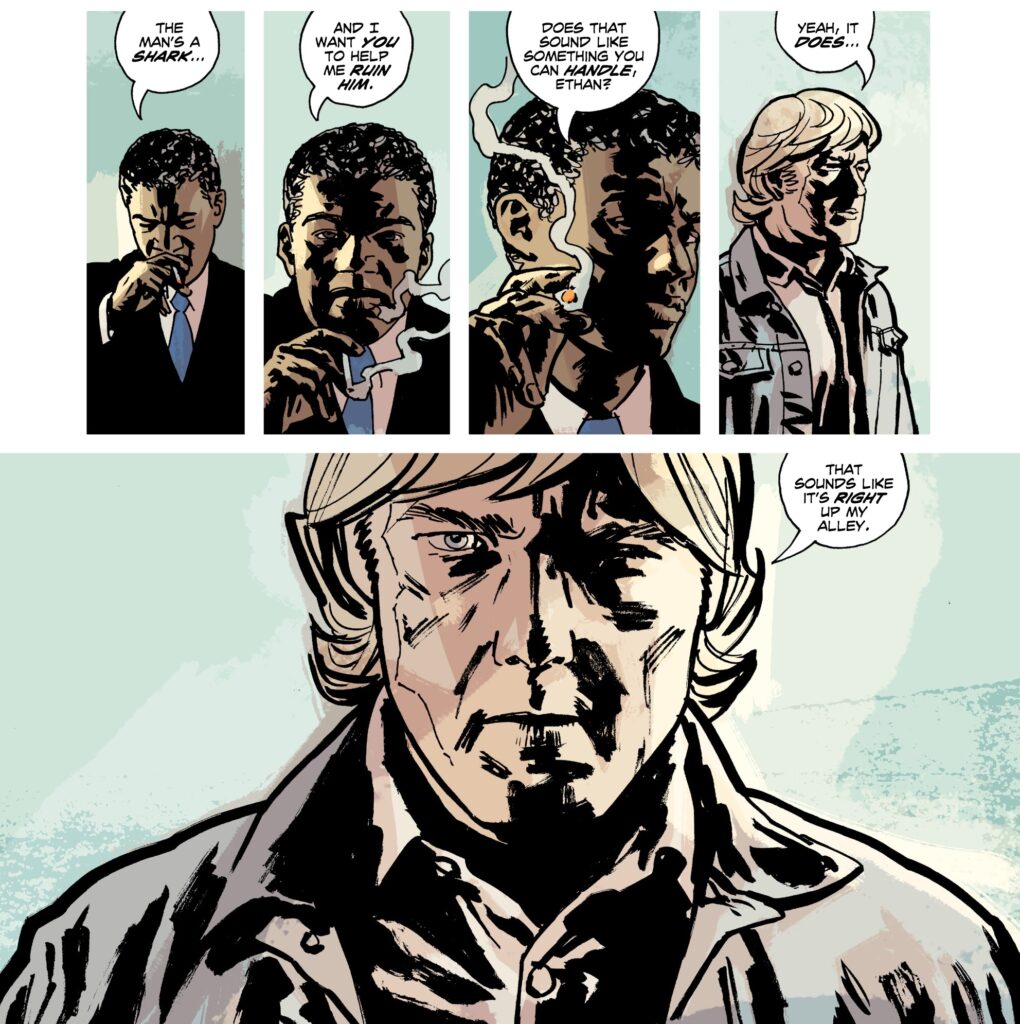

It’s this sort of extra levels I find missing in some of Brubaker’s other comics. For instance, when it comes to revisionist forays into vigilante justice, for every compelling tale that elevates or reinvents his influences and obsessions, like the devastating second arc of Criminal, you get one that comes across as uninspired fanfiction or as an on-the-nose illustrated essay about its genre or medium, like Kill or Be Killed.

Kill or Be Killed #4

I love the whole subgenre of stories deconstructing vigilantism’s problematic appeal by engaging with its practical and moral questions as much as – or perhaps even more than – I like thrillers that play it straight. While promising to daringly dramatize the inherent tensions of this narrative tradition, however, Kill or Be Killed mostly settles for directly discussing each trope and device with the reader… I guess this is meant to be metafictional, but it feels more like an obnoxious commentary track constantly asking you: ‘Do you get what I’m doing?’

Given that the book has such a clear mission statement, I miss not only Tarantino’s inventiveness, but also the unsettling weirdness and the thematic breadth of a film like Anders Thomas Jensen’s Riders of Justice or a comic like Steve Gerber’s and J.J. Birch’s Foolkiller. Even when Kill or Be Killed turns into a walls-closing-in-on-upper-class-white-guy-versus-xenophobic-stereotypes kind of tale, the result lacks the irony of a show like Ozark (whose subversive gesture was only fully acknowledged at the very end). This is all the more frustrating because the art team of Sean Phillips and colorist Elizabeth Breitweiser give it their best, making the series look nothing less than absolutely stunning.

By contrast, I’m having a much more enjoyable time with Brubillips’ other ongoing project, Reckless, which I’ll discuss in a couple of weeks…

Reckless: Destroy All Monsters