Every once in a while, Dead Reckoning – an imprint of the U.S. Naval Institute’s book-publishing division – sends me graphic novels to review in Gotham Calling. Last year they sent me The Lions of Leningrad and The Stretcher Bearers, but, with so much attention on the present-day war, I felt little inclination to delve into historical fiction.

I’ve finally gotten around to them and it was worth it… Well, one of the books was, anyway. Below, you’ll find some thoughts on these two comics and on another one I recently read.

Let’s start with the best of the lot.

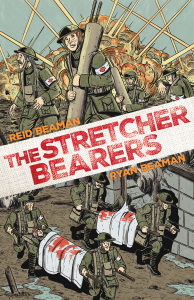

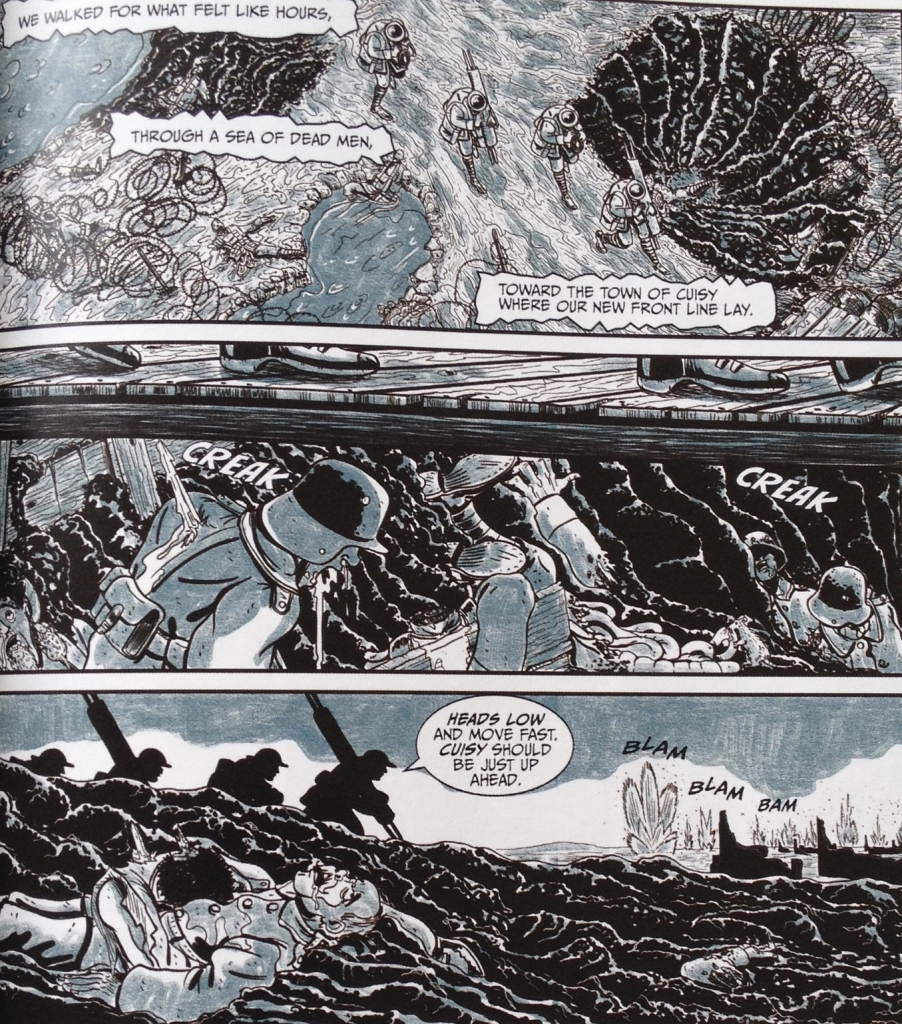

Co-written by brothers Reid and Ryan Beaman – with art by the former and letters by the latter – The Stretcher Bearers follows a group of Americans in World War I whose job is to venture into the battlefield and bring wounded soldiers back to the nearest medical facilities. As the book progresses from battle to battle, and from trench to trench, we get to know these men’s personal dynamics and tensions and, through them, to witness up close the harrowing violence of one of history’s most brutal conflicts as conveyed by artwork that feels immersive yet not exploitative.

For all the detail and authenticity, there’s a no-frills sharpness to Reid Beaman’s drawings, providing enough lines for you to get the picture without any attempt at photorealism (thus making the comparison to Harvey Kurtzman’s classic war comics even more inescapable). The same relative mix of identification and removal goes for the coloring, whose blue-green monochrome softens the gruesomeness while intensifying the sepia-tinged mood of a distant era captured in some old photograph.

The Stretcher Bearers

The Stretcher Bearers

By focusing on a medical rescue team, we are thrust into the middle of combat action without necessarily rooting for one side against the other in jingoistic, bloodthirsty terms… Our POV characters aren’t trying to kill, but to save lives.

Despite the ensuing feeling of frustration, pointlessness, and helplessness in trying to pick a few wounded among all the massive slaughter, however, The Stretcher Bearers doesn’t question the conflict’s motives or the US soldiers’ duty – it seems to sympathize with their necessary sacrifice and it doesn’t waste time on speeches about the Germans’ own humanity. Indeed, one of the things I liked was precisely how matter-of-fact the script is, for the most part. Like with the artwork, the tendency isn’t towards sensationalism, preachiness, or indignation. Instead, the writers let the documented action speak for itself.

This general dryness renders the book’s few ventures into sentimentality all the more powerful:

The Stretcher Bearers

The Stretcher Bearers

It would be going too far to say that The Stretcher Bearers reaches the gold standard of WWI comics set by Charley’s War and It Was the War of the Trenches (brilliantly translated), but the result is not that far out of their league.

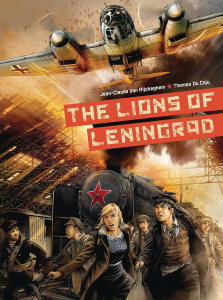

In fact, I’ve quite enjoyed almost all of what I’ve read of Dead Reckoning’s output. So far, the only real stinker in the bunch was The Lions of Leningrad…

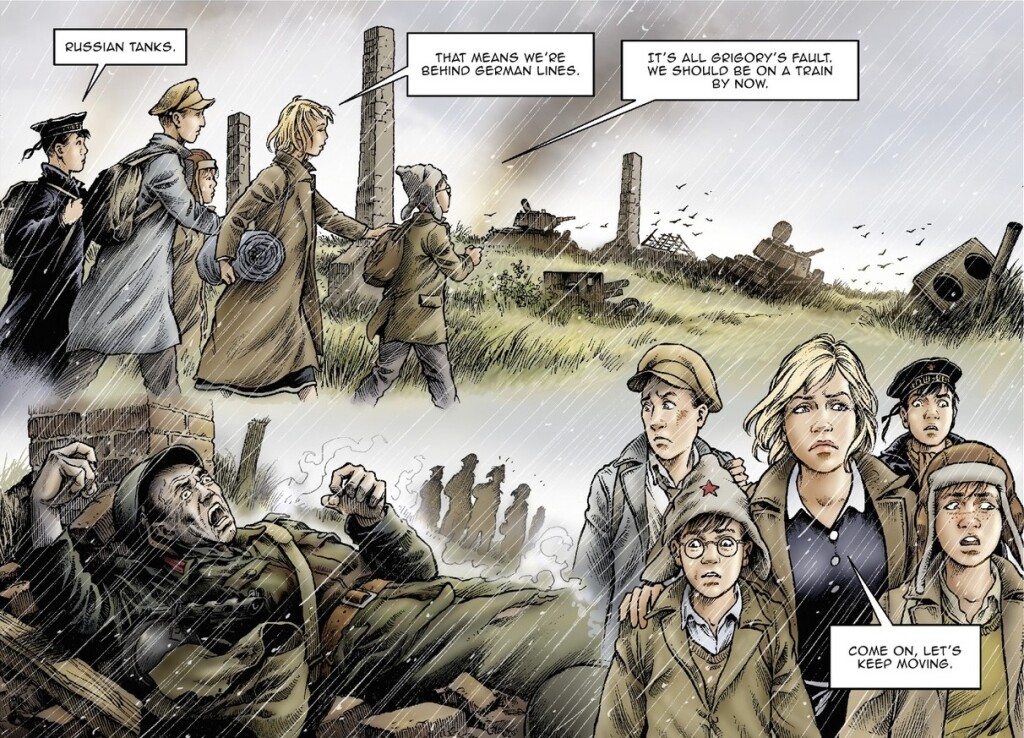

The Lions of Leningrad

The Lions of Leningrad

A translated Belgian bande dessinée, The Lions of Leningrad is framed around a flashback to 1941 in which four Russian teens struggle to get by during the infamous siege of the titular city, making ever larger moral compromises. There is nothing wrong with this premise, as the siege of Leningrad makes for a fascinating, if bleak, historical setting. This terrible episode of World War II has great potential for dramatization, especially if you manage to individualize the characters’ personal dramas, like The Stretcher Bearers did.

Unfortunately, writer Jean-Claude Van Rijckeghem doesn’t make any of the cast members particularly likable or interesting (or even particularly memorable, for that matter) – they’re essentially one-note figures with simple arcs, which makes the story seem too schematic, thus substantially lessening the impact of both the romantic subplot and the final twists.

It doesn’t help that Thomas du Caju, despite a keen eye for mise en scène and an impressive rendition of the wintery atmosphere, has a stiff art style that constantly undermined my engagement with the comic’s emotion as well as action. (It helps even less that the lettering in Dead Reckoning’s edition is sub-par, often being unevenly – and awkwardly – distributed within the word balloons.)

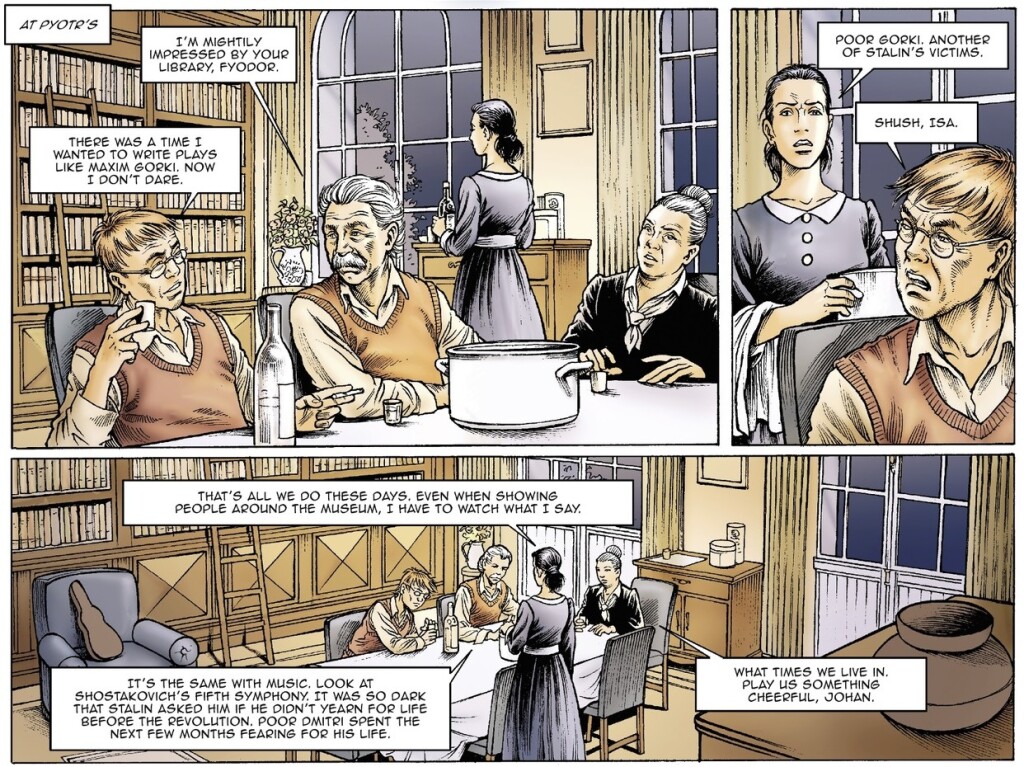

Ultimately, The Lions of Leningrad feels less concerned with its protagonists than with delivering a political indictment of Stalin’s Soviet Union:

The Lions of Leningrad

The Lions of Leningrad

The comic’s central point is that, even though the Nazis were attacking the USSR and carrying out the siege of Leningrad, much of the suffering stemmed from reasons that had to do with the Soviet Union itself, namely from an authoritarian system full of brute, lying, venal bastards.

This could’ve been a powerful angle, especially in this day and age when dessacralizing narratives of Russian unity and bravery in WWII could be seen as a ‘fuck you’ to Vladimir Putin’s rhetoric of national pride and historically-informed militarism. Yet the final product sounds like little more than basic anticommunism… Given that the Nazis are almost invisible here, the environment of extreme poverty and corruption practically comes across less like a circumstantial product of the war than like a structural feature of the USSR, thus reproducing a familiar image that is associated with different eras of the regime. I haven’t much fondness for Stalinism or for the dictatorship that followed (or for Putin’s current imperialism), but I could do without such a charmless comic trying to force-feed me its narrow, didactic notions about Soviet life.

In search of a palate cleanser, I picked up another war book with a leonine title…

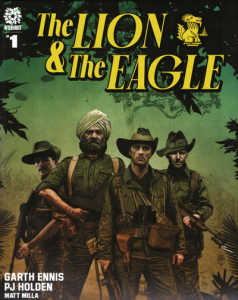

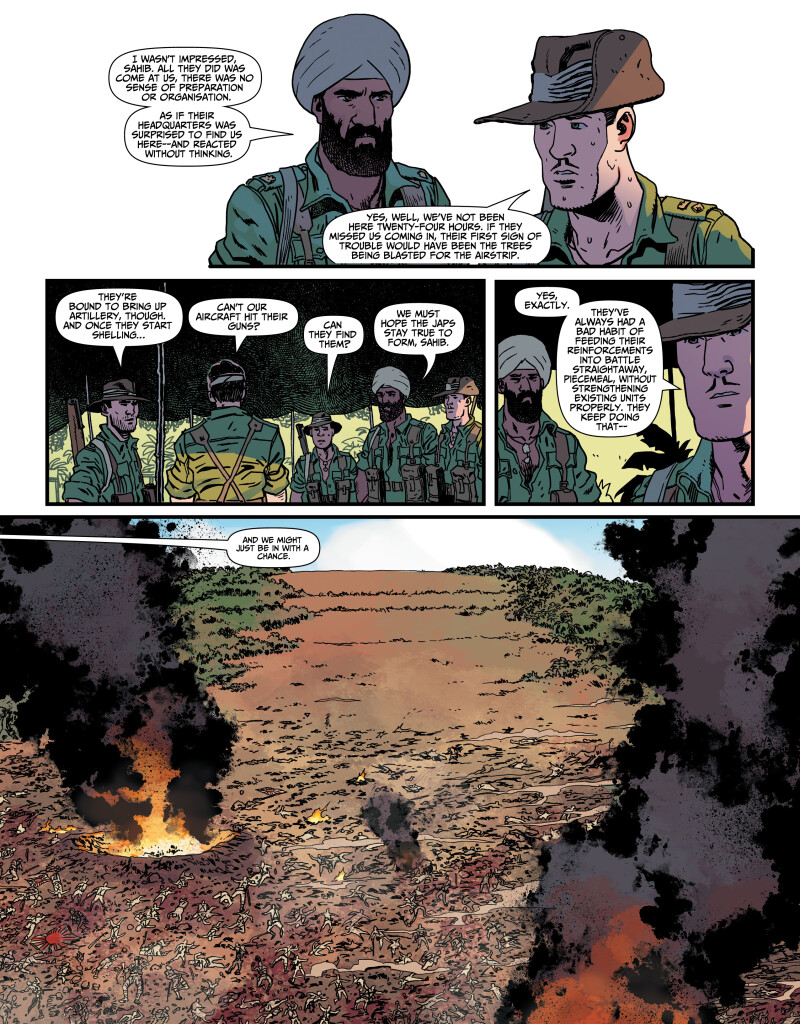

The Lion & the Eagle

The Lion & the Eagle

Garth Ennis’ millionth war comic, The Lion & the Eagle, illustrated by PJ Holden with pungent colors by Matt Milla, is set in 1944 Burma, where a British special force – coordinated with American and Chinese allies – gets dropped in the middle of occupied territory and has to fight the seemingly fearless Japanese. If the latter appear as an almost ghostly presence/force of nature striking from the jungle without any discernible individuality (pretty much like the Vietnamese in so many US narratives), the book nevertheless undercuts the usual ethnic homogeneity by featuring an Indian contingent among the British troops. This, along with the setting, is what sets The Lion & the Eagle apart from so many other works by Ennis, who thus gets to indulge in his fascination with war’s muddy ethics and logistics while indirectly – and provocatively – intervening in the ongoing conversation about race and colonialism.

At first sight, Ennis appears to be coasting, not bothering to develop most characters beyond the stiff-upper-lip Colonel Keith Crosby and reducing 90% of the action to dialogue, including plenty of stuff that could’ve easily been shown rather than described. Seriously, there are so many pages full of people explaining details about military organization, strategy, and the overall geopolitics that letterer Rob Steen must’ve put in at least as much work as the artist on this one.

Perhaps Ennis sought to convey a certain rhythm of war, with lengthy stretches of quiet, practical talk punctuated by peaks of adrenaline and action… or perhaps he has just grown overconfident in his way with dialogue. To be fair, the result is still pretty readable, at least if you have a keen interest in WWII history.

That said, the most captivating thing about The Lion & the Eagle is the fact that it’s a book about racism, both capturing a racist view of the Japanese (a plot point concerns the refusal to leave wounded behind because, if captured by the Japanese, they’re bound to be savagely tortured) and complexifying the various racial dynamics at play.

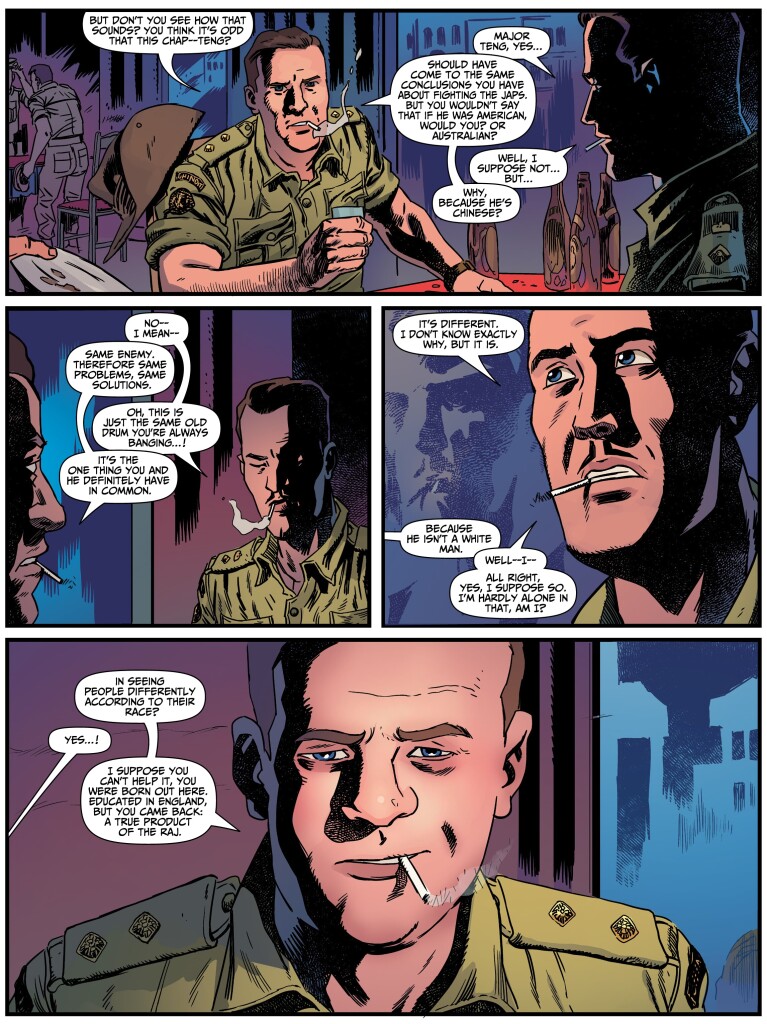

The Lion & the Eagle

The Lion & the Eagle

As you can see, some of the themes are spelled out in the dialogue as well. The key scene in the entire comic is a lengthy conversation in issue #3 where Ennis suddenly introduces a communist called Pine to air an anti-imperialist perspective (‘We’re fighting to reconquer a country that ain’t ours, and we’re using blokes from another country that ain’t ours to do it.’) and address possible retorts to such views. Having fulfilled his rhetorical duty, Pine mostly disappears afterwards, yet The Lion & the Eagle continues to engage with his words: in issue #4, a Sikh soldier makes a point of clarifying that he’s a volunteer and, in the end, Crosby once again reassesses the colonial angle.

Regardless of the heavy-handedness, Ennis did find a truly inspired context in which to explore this topic, as the whole thing ends up revolving around different kinds of occupiers and occupied negotiating messy identities and alliances… It’s just too bad he didn’t bother to invest in the story itself as much as in the comic’s broader ideas and historical research.