Chuck Dixon has written hundreds of Batman comics. On top of his lengthy run in Detective Comics (1992-1999), he penned his fair share of Catwoman and Legends of the Dark Knight issues, having also pioneered the ongoing series Robin and Nightwing, as well as the most awesome Batman spin-off from the ‘90s, Birds of Prey. Dixon created fan-favorite characters like Spoiler and Bane. Plus, he did a ton of fill-ins, specials, and mini-series, including the knockout crime yarns GCPD, Gordon’s Law, and Blackgate. Between this and his stint on Green Arrow (which often shared characters and plotlines with the Bat-titles), it was not uncommon for Dixon to have half-a-dozen Batman-related comics out each month for much of the ‘90s. He went on to relaunch Batman and the Outsiders in 2007 and, after a hiatus, recently returned to DC with the limited series Bane: Conquest.

Despite this impressive track-record and a loyal fanbase, Chuck Dixon doesn’t usually make the cut in debates about the best Batman writers. In part, I suspect his work isn’t more acclaimed because it’s not as show-offy as Frank Miller’s or Grant Morrison’s – Dixon is more of a gun-for-hire who prefers no-fuss storytelling rather than trying to reinvent the wheel (Howard Hawks, Leigh Brackett, David Mamet, and Donald E. Westlake are obvious influences). This approach may strike some as lacking ambition, but I think it’s an art in itself: Dixon has a talent for figuring out each franchise’s primordial appeal and delivering it in spades, perfecting the formula to maximum effect. As far as 1990s’ Batman comics go, if Alan Grant’s issues were punk and Doug Moench’s were heavy metal, then Chuck Dixon’s were reliable pop-rock hits with catchy guitar riffs.

Dixon’s attitude harkens back to his proud pulp background, having honed his craft in the 1980s with straight-up adventure titles like Airboy, Evangeline, Winter World, and Savage Sword of Conan.

So, when I describe Chuck Dixon’s Batman comics as ‘grounded,’ I don’t mean to say they’re bland or hackneyed. In fact, he rarely phones it in: even a gig that could’ve been mere a cash-in, like Batman versus Predator III: Blood Ties, turns out to be highly entertaining (in contrast to Doug Moench’s and Paul Gulacy’s godawful Batman versus Predator II: Bloodmatch, which was an insipid mercenary work lamely padded to fill the page count). What I mean is that Dixon’s comics tend to be anchored in fleshed-out characterization and cohesive world-building – although his stories aren’t exactly ‘realistic,’ they operate through very recognizable rules and follow a solid internal logic.

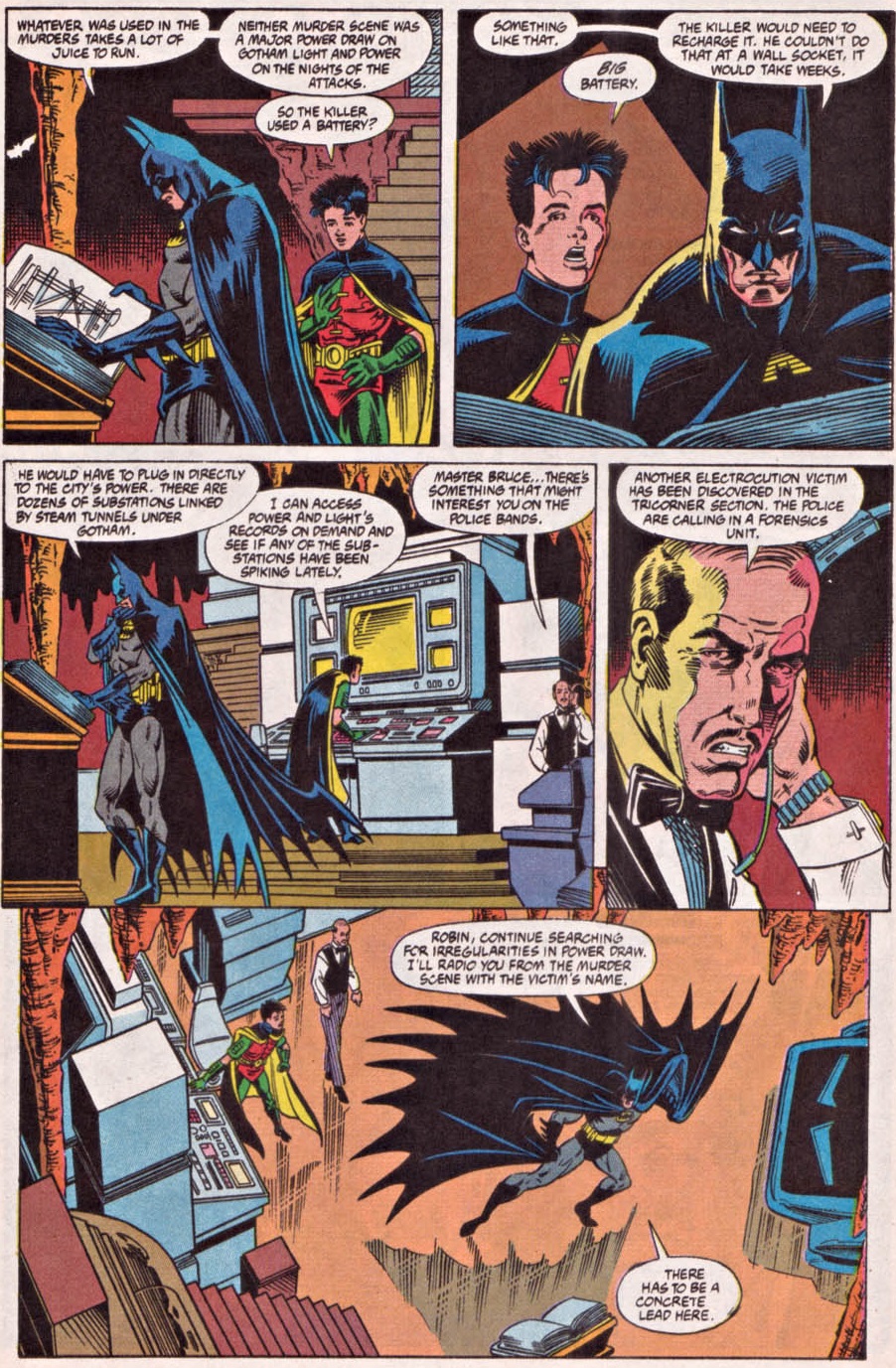

But let’s start at the beginning. Understandably impressed with Chuck Dixon’s hardboiled scripts for The Punisher, in 1990 editor Denny O’Neil hired him to write the first solo Robin mini-series, with art by Tom Lyle (who had already worked with Dixon on Airboy and Strike!). The duo fit into the Dark Knight’s corner of the DC Universe like a glove, spitting out solid thrillers that were unapologetically escapist yet did not condescend to the readers. Soon, Dixon and Lyle took over Detective Comics and their efforts together come very damn close to my platonic ideal of Batman stories. In a move that’s not as obvious as it may seem, Dixon – who went on to helm Detective Comics for years (mostly in collaboration with artist Graham Nolan) – made sure to justify the series’ title by featuring plenty of detective work. Fortunately, the man can spin a mystery and churn out a damn compelling investigation.

Detective Comics #644

Detective Comics #644

The Dynamic Duo wasn’t the only one doing the detecting… Chuck Dixon devoted a lot of space to the GCPD, developing several of its officers. The result really felt like a detective book. For example, in ‘Shifting Ground’ (Detective Comics #721), set during the Cataclysm crossover, Dixon had three separate groups of characters investigating the identity of Quakemaster – the villain holding the city for ransom – and each was able to track him down through different processes of deduction (the disparate strands then came together in Robin #53). Other cool mystery tales included the classic ‘A Bullet for Bullock’ (Detective Comics #651) as well as ‘The Forgotten Dead’ (Nightwing #24) and ‘The Obtuse Conundrum’ (Robin #81).

Indeed, Dixon often made a point of challenging the heroes’ intellect. A central aspect of his version of Bane was precisely the fact that this villain should be a match for Batman on every level, including his brilliance. In Bane of the Demon, he commits an ancient text to memory eidetically. In Bane: Conquest, the two characters temporarily join forces and are able to plot an escape underneath their captors’ noses by constantly switching languages (including Portuguese, Dhari, and Latin).

It wasn’t all cerebral games, either. A consciously visual storyteller, Chuck Dixon usually scripts thrillers with clear geography and relentless forward momentum. In particular, he tends to write tense, claustrophobic set pieces revolving around people trapped in confined spaces. Also helping with the fast pace is his knack for snappy dialogue:

Batman #467

Batman #467

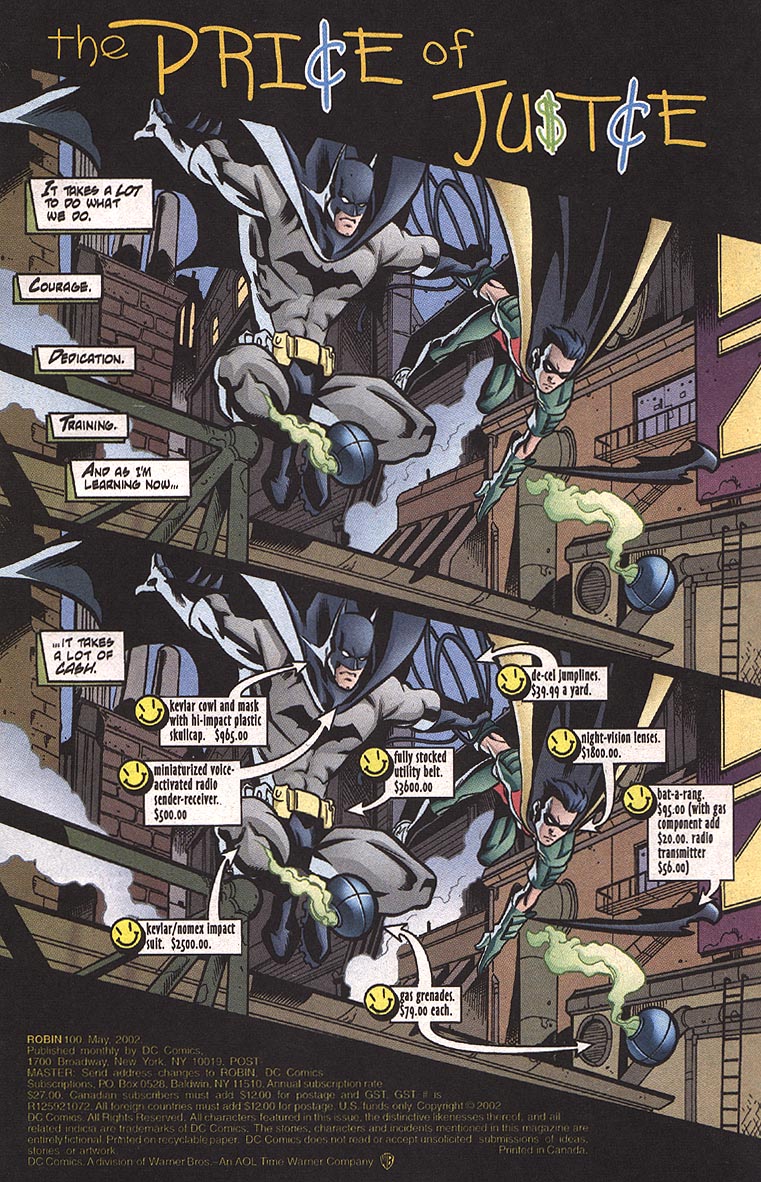

We are very far from the kind of superhero deconstructionism that tears the genre apart by exposing its inconsistencies and uglier subtext. Chuck Dixon seems more interested in imagining how it could work, integrating pseudo-realistic elements – like the street-level perspectives of the police and small-scale criminals – without going too far in terms of breaking the required suspension of disbelief.

For a particularly fun way to go about it, check out the issue he did with the price tags for the Dynamic Duo’s various expenses…

Robin (v4) #100

Robin (v4) #100

What brings it all together, though, is Dixon’s way with characters. He always made sure to get a firm take on what made each cast member tick. Check out how, in this career interview, he efficiently synthesized his understanding of the Caped Crusader and the Punisher: ‘Batman is the zealot driven by childhood trauma. Thus, a costume and all the toys and the sense of the romantic. He also has a code of fair play and strict rules of engagement. Punisher was traumatized as an adult, so he becomes an exterminating son-of-a-bitch using any weapon that will get the job done. He recognizes no rules.’

Besides getting to the heart of characters, Dixon is a master at organically conveying that heart to the readers, whether it’s through actions or through poignant intimate moments. Take the story he did for Batman Chronicles #1 about a gang hijacking a train with James Gordon inside. It was a taut little yarn, but behind its apparent simplicity we gained access to Jim’s thoughts about how it felt to be out of the police force (he had temporarily quit at the time), about his doubts over trusting Batman (this was after Knightfall), and about how the Huntress reminded him of his daughter (Batgirl). Those eighteen pages turned out to be a touching, well-executed piece of characterization. Similarly, back in 1999 Dixon did three memorable issues that may seem like little more than Nightwing bonding with Robin (Nightwing #25), Oracle (Birds of Prey #8), and Batman (Detective Comics #725) but are misleadingly superb, drawing on the characters’ shared history and wonderfully nailing each of their personalities. (Robin #67, in which Nightwing and Robin travelled together to No Man’s Land’s Gotham City, was also an excellent character study about their brotherly relationship.)

Bear in mind that that I’m not just talking about your usual macho voices. Robin was a series about adolescence, oozing with self-doubt and a healthy dose of lighthearted humor. Most of Birds of Prey’s main characters (heroes and villains) were women. Dixon also sought to establish a neat friendship between Stephanie Brown and Cassandra Cain (they first met in Robin #88 and later developed their relationship in Batgirl #20). Hell, one of the strongest candidates for Dixon’s most enjoyable book ever, Batgirl: Year One (co-written with Scott Beatty), closely followed the point-of-view of a young Barbara Gordon…

Batgirl: Year One #1

Batgirl: Year One #1

In terms of characterization, one of the few missteps I can think of is when Alfred left – in the aftermath of Knightfall – and Bruce Wayne proved utterly inept at household chores, screwing up everything, from making a tuna sandwich to doing the laundry (come on, he’s Batman, if anything he would’ve overcompensated by approaching each task with too much zeal!). Overall, though, hardly a note ever rang false in Chuck Dixon’s stories.

The other aspect that makes these comics ‘grounded’ is their tight cross-continuity. As a fanboy, Dixon clearly has a blast with this stuff. There are all sorts of interconnections, even when they don’t call attention to themselves (like the overlap between the Dynamic Duo’s cases in Detective Comics #683 and Robin #15, or the subplot from Robin #93-94 that gets resolved in Birds of Prey #40, or the guest-appearances by Blue Beetle in Nightwing #63, Robin #96, and Birds of Prey #37, all of which dealing with the fallout of Dixon’s Joker: Last Laugh crossover).

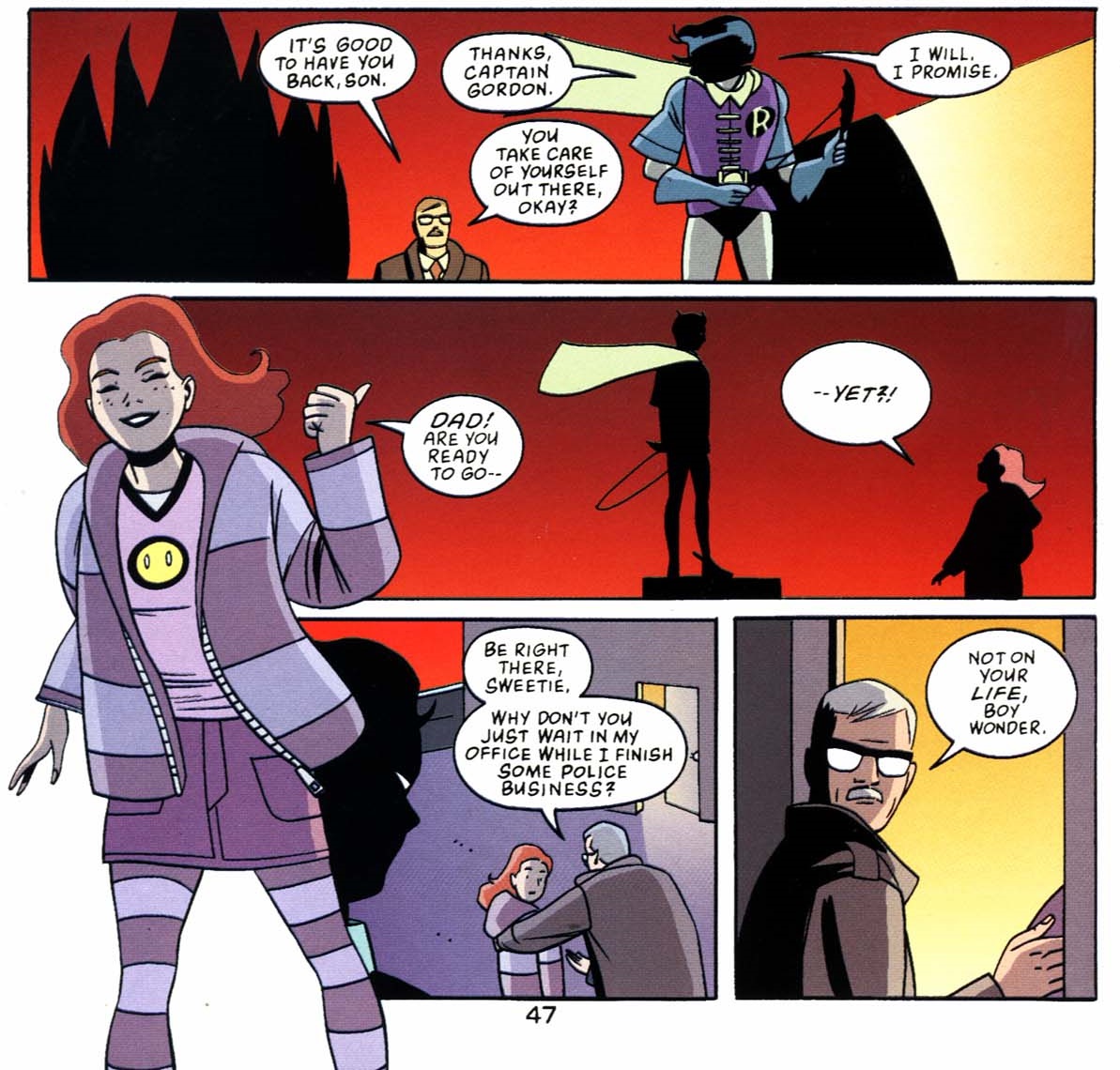

I especially like how this moment from the mini-series Robin: Year One (about Dick Grayson’s debut as Robin)…

Robin: Year One #4

Robin: Year One #4

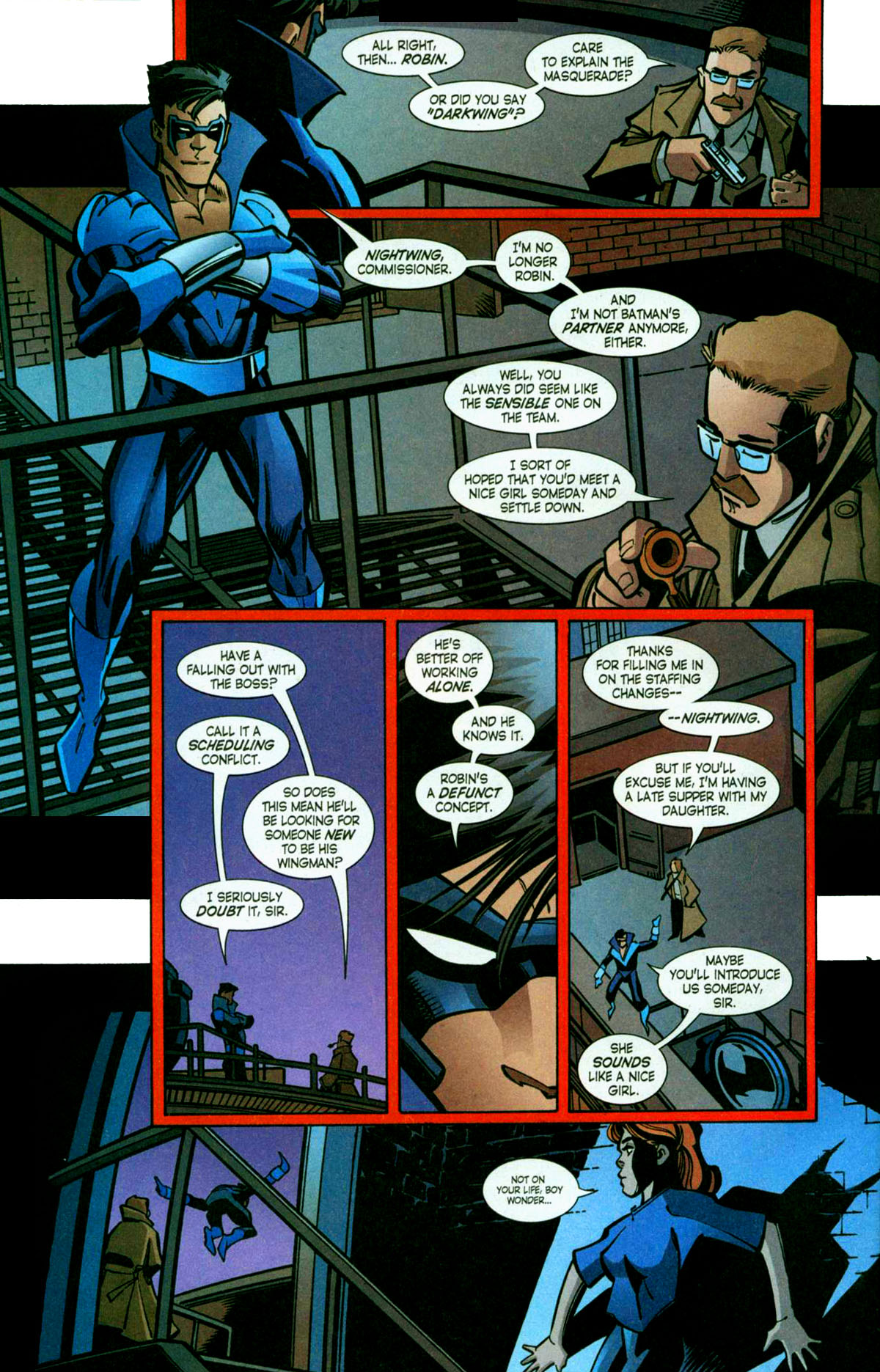

…was riffed on years later, in the story arc ‘Nightwing: Year One’ (about Dick Grayson’s debut as Nightwing):

Nightwing #104

Nightwing #104

Chuck Dixon went out of his way to develop a discernible geography for Gotham City and its surroundings (Tricorner Island, the fancy Gotham Heights neighborhood, the chaotic nearby town of Blüdhaven…), repeatedly visiting places like the striptease joint Stripping Post (Batgirl: Year One #5, Nightwing #65 and #104…). There were also recurring brands (some created by him, some borrowed from other DC comics), including the Irish fast food chain O’Shaughnessy’s (which shows up, for example, in Robin #20, Batman Annual #23, Nightwing #10, and Green Arrow #110) as well as the soda drink Zesti Cola (Detective Comics #645-646, Catwoman #19, Robin #61, and Joker: Devil’s Advocate, among many others).

In the case of Zesti Cola, it became more than a generic ersatz-brand – Dixon made it pay off with a couple of entertaining storylines exploring the company behind the drink, in the Psyba-Rats mini-series and the Birds of Prey: Revolution one-shot. Likewise, after gradually establishing the children’s franchise Crocky the Crocodile (Detective Comics #668 and #682, 1996’s Man-Bat mini-series…), Dixon made it the main focus of Robin #42.

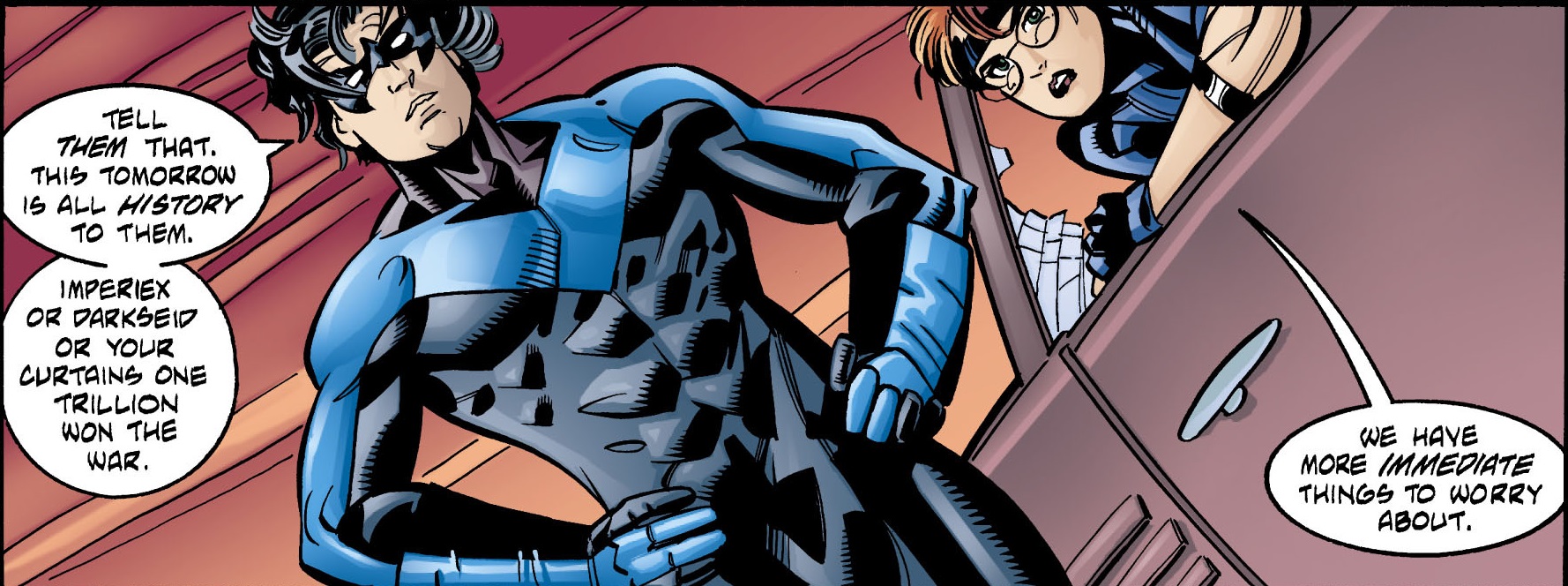

The more you read, the more you felt like you understood this world. You knew that Zesti and Soder Cola were popular drinks and you got used to thinking of Curtains as the DCU’s version of Windows. You were thus able to share the characters’ specific pop culture references, like in this scene where Nightwing and Oracle travel to the future:

Nightwing: Our Worlds at War

Nightwing: Our Worlds at War

This is exactly the kind of approach that appeals to me. These comics were populated by tons of people whose names and histories became familiar, giving the impression that they continued to live their own personal sagas between appearances, on the sidelines of the Dark Knight’s adventures.

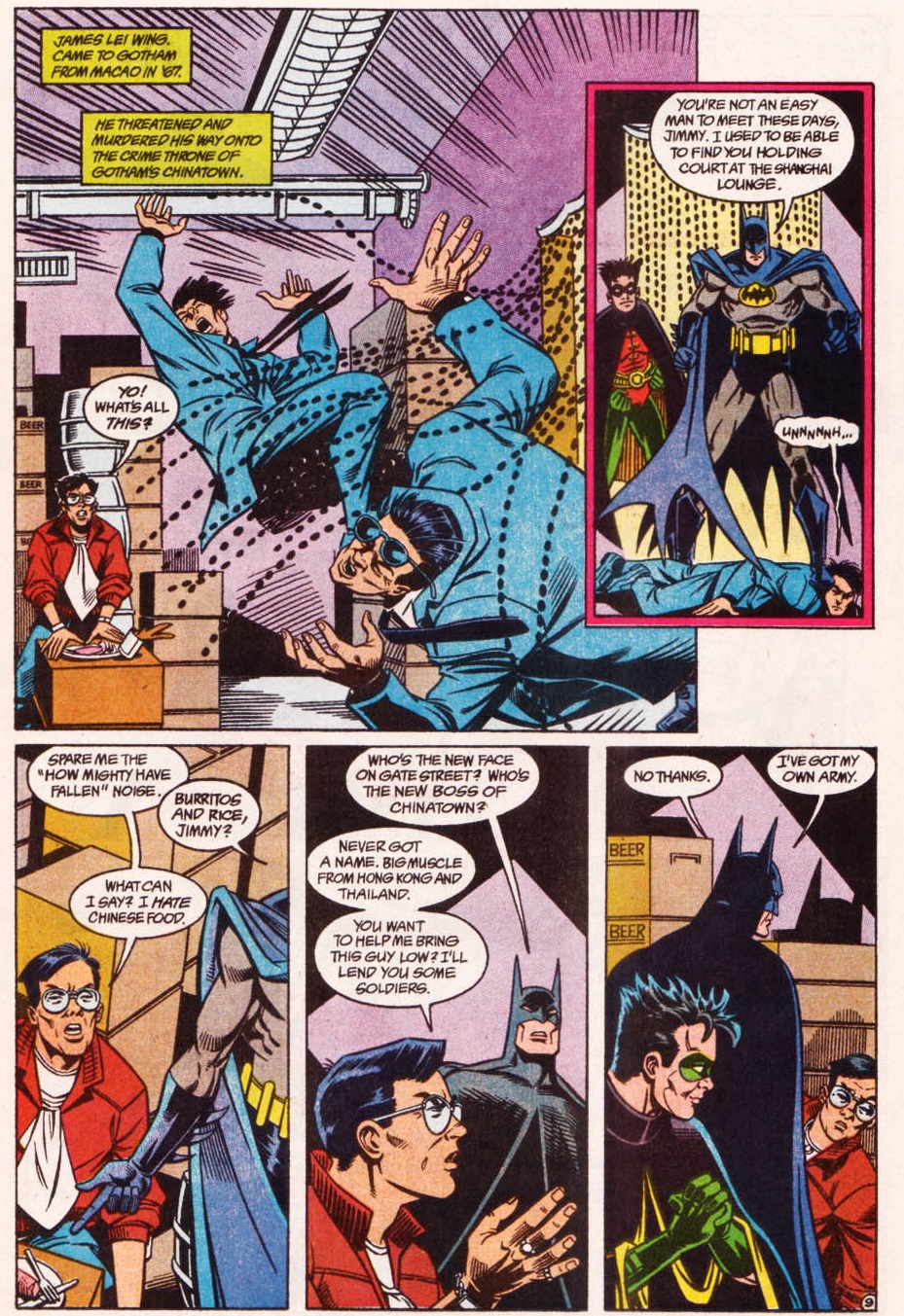

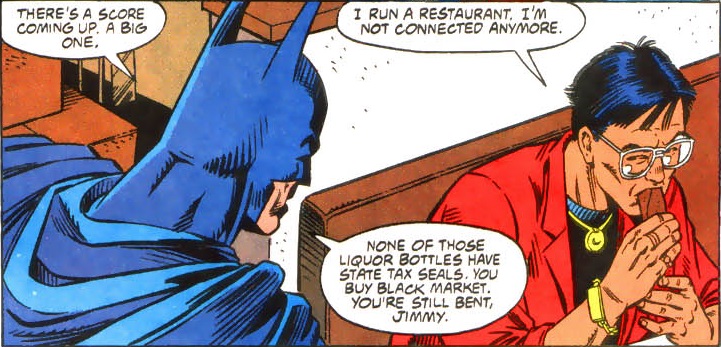

Remarkably, a whole range of small-time players kept showing up again and again throughout the years, like the crooked informant Jimmy Wing…

Detective Comics #648

Detective Comics #648

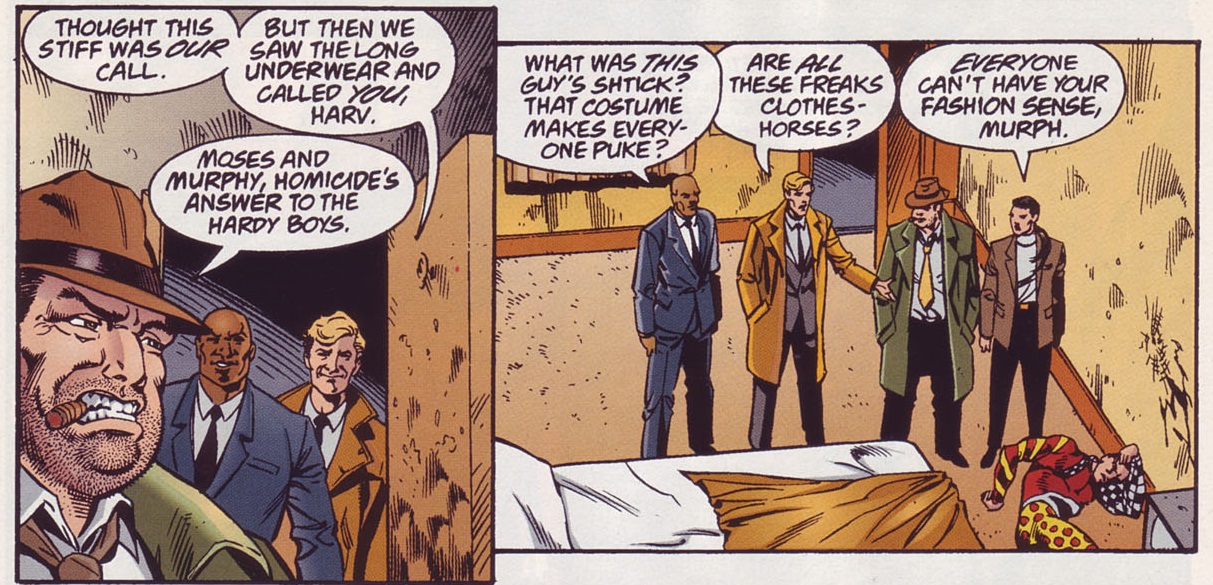

…or Homicide detectives Moses and Murphy, whose banter was always a feast of gallows humor…

Detective Comics #691

Detective Comics #691

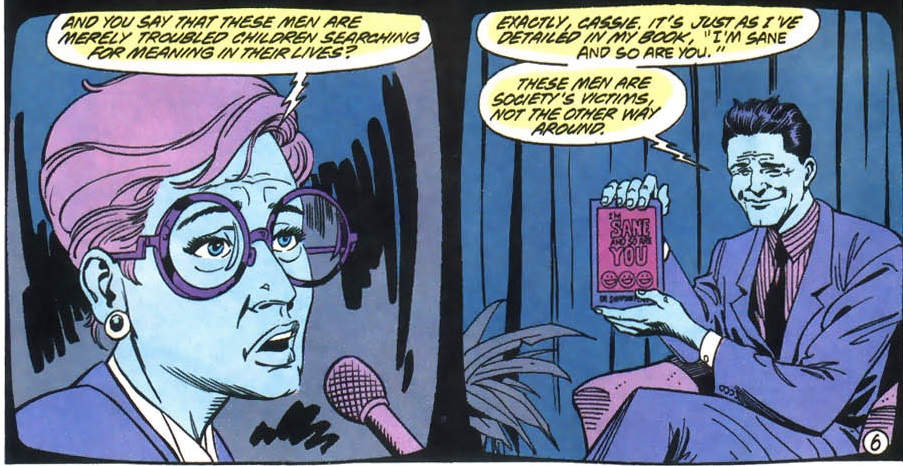

…or the Arkham Asylum psychologist Simpson Flanders (yep), who started out as a mean-spirited satire of liberal pop psychology (albeit an amusing one since almost by definition Arkham inmates are an unredeemable murderous lot) reminiscent of Doctor Bartholomew Wolper in The Dark Knight Returns.

Detective Comics #662

Detective Comics #662

(In line with this joke, Flanders kept being viciously abused by different villains, until he was eventually eaten by Killer Croc!)

As you can tell by these last examples, Dixon’s comics were not devoid of a certain iconoclastic sense of humor. I will talk more about that next week.