Last week I mentioned that Chuck Dixon is an old-school pro whose work in Batman comics (especially during his most prolific period, in the 1990s), rather than blow up the status quo, was all about gripping narratives that stayed true to the characters. Yet it can be misleading to think of him as a mere journeyman who has mastered meat-and-potatoes storytelling. There is also a caustic side to Dixon’s authorial voice, including a penchant for corrosive comedy and biting social commentary. This has enabled him to engage with personal idiosyncrasies like his film tastes and political views.

Catwoman (v2) #29

Catwoman (v2) #29

I’ve written before about Chuck Dixon’s key contribution to our ability to imagine Gotham City’s cinema culture. This no doubt stems from the fact that Dixon is a film buff – one who not only borrows plenty of ideas from the movies, but who also infuses that passion into the world he creates. In Robin Annual #1 (the coolest issue of the lame Bloodlines crossover), Dixon introduced the Psyba-Rats, a team of teen techno-thieves that included the mutant Channelman, who enters television systems and tweaks Hollywood classics. One of the best friends of Tim Drake (Robin’s civilian identity) was a geek called Sebastian Ives who loved schlocky sci-fi flicks (leading to a fun sequence at a drive-in, in Batman versus Predator III). Detective Harvey Bullock’s obsession with old movies played a role in the one-shot Bullock’s Law. Plus, although it’s not explicit, I’m convinced the characters in Bane: Conquest keep quoting one-liners from Commando…

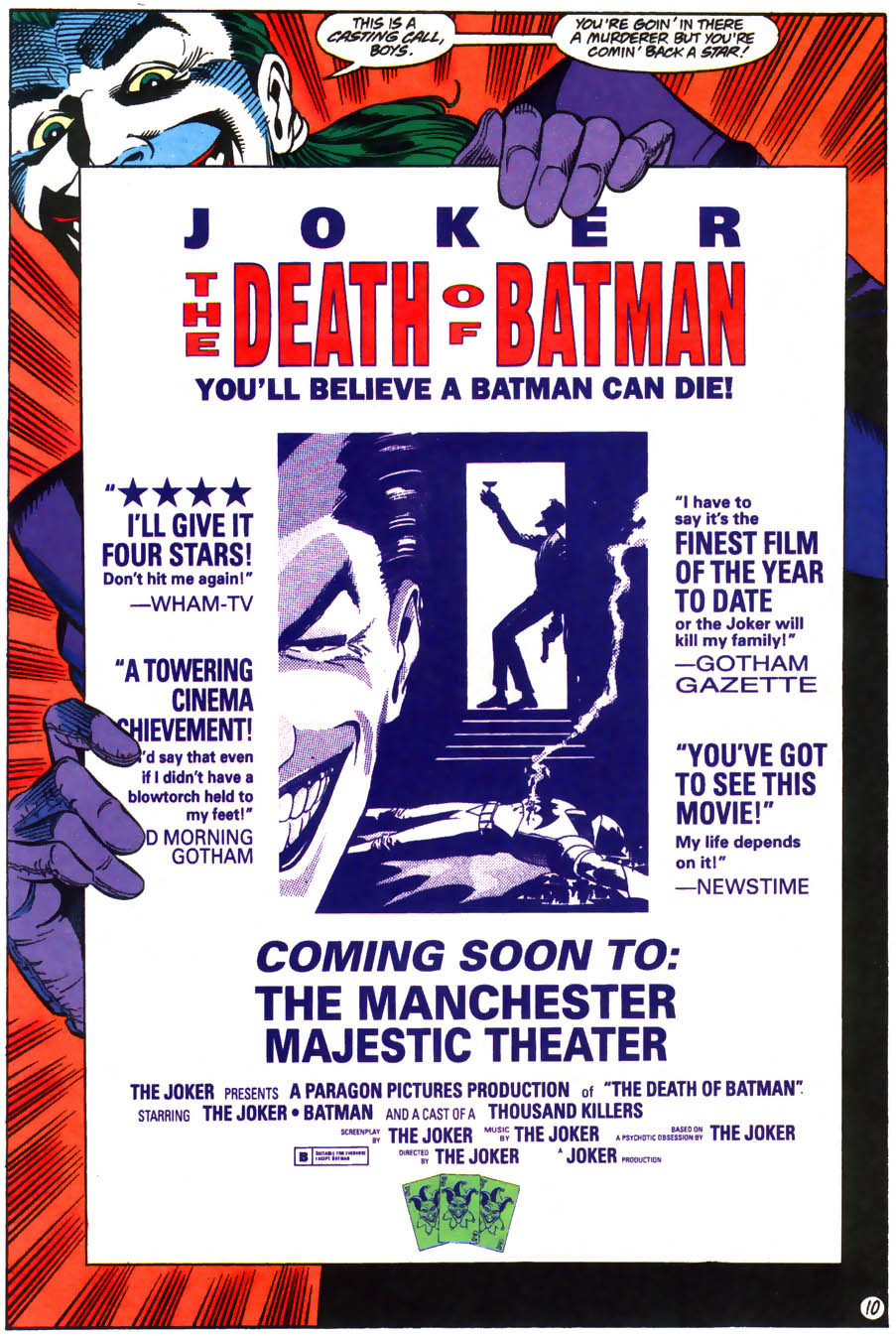

And then there is Detective Comics #671-673, where the Joker gets funding to do a film in which he actually kills Batman (because Hollywood producers are almost as insane as he is).

Detective Comics #672

Detective Comics #672

(Did I mention Dixon is one of greatest Joker writers?)

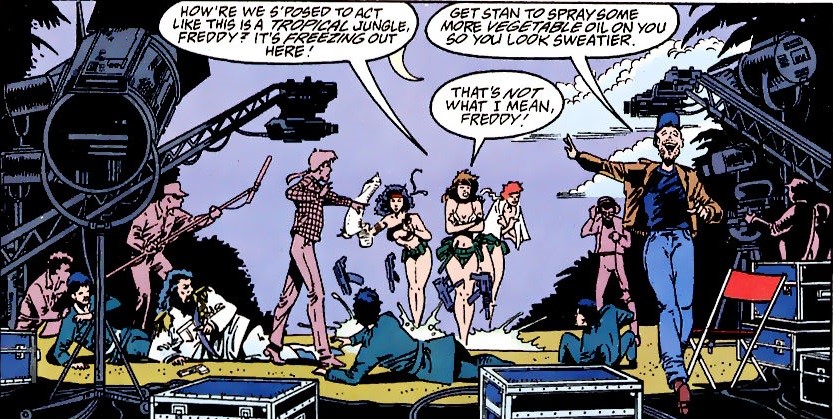

Another madcap satire, ‘More Edge More Heart’ (Catwoman #20) opens with a shot of the film Lethal Honey III, full of busty, bikini-clad babes shooting automatic weapons, framed by Catwoman’s quip: ‘Movie people are always saying that their industry is almost a hundred years old. So why is it still in puberty?’

It only gets better from there.

Catwoman (v2) #20

Catwoman (v2) #20

In this hilarious story arc, a sleazy producer hires Catwoman to steal a screenplay from the successful competition in order get a knock-off production ready in time for the blockbuster’s release. This leads to a wonderful payoff in the second part, ‘Box Office Poison.’

By repeatedly having fun at the expense of the film industry, Chuck Dixon isn’t just displaying his interest and knowledge regarding the inner workings of the movie business. He is also partaking (deliberately, I assume) in a long tradition of love/hate parodies of this milieu – a subgenre that’s part of the industry’s own history, as seen in films such as Victor Fleming’s Bombshell, Robert Altman’s The Player, David Mamet’s State and Main, and the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caeser!, not to mention Quentin Tarantino’s uneven Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.

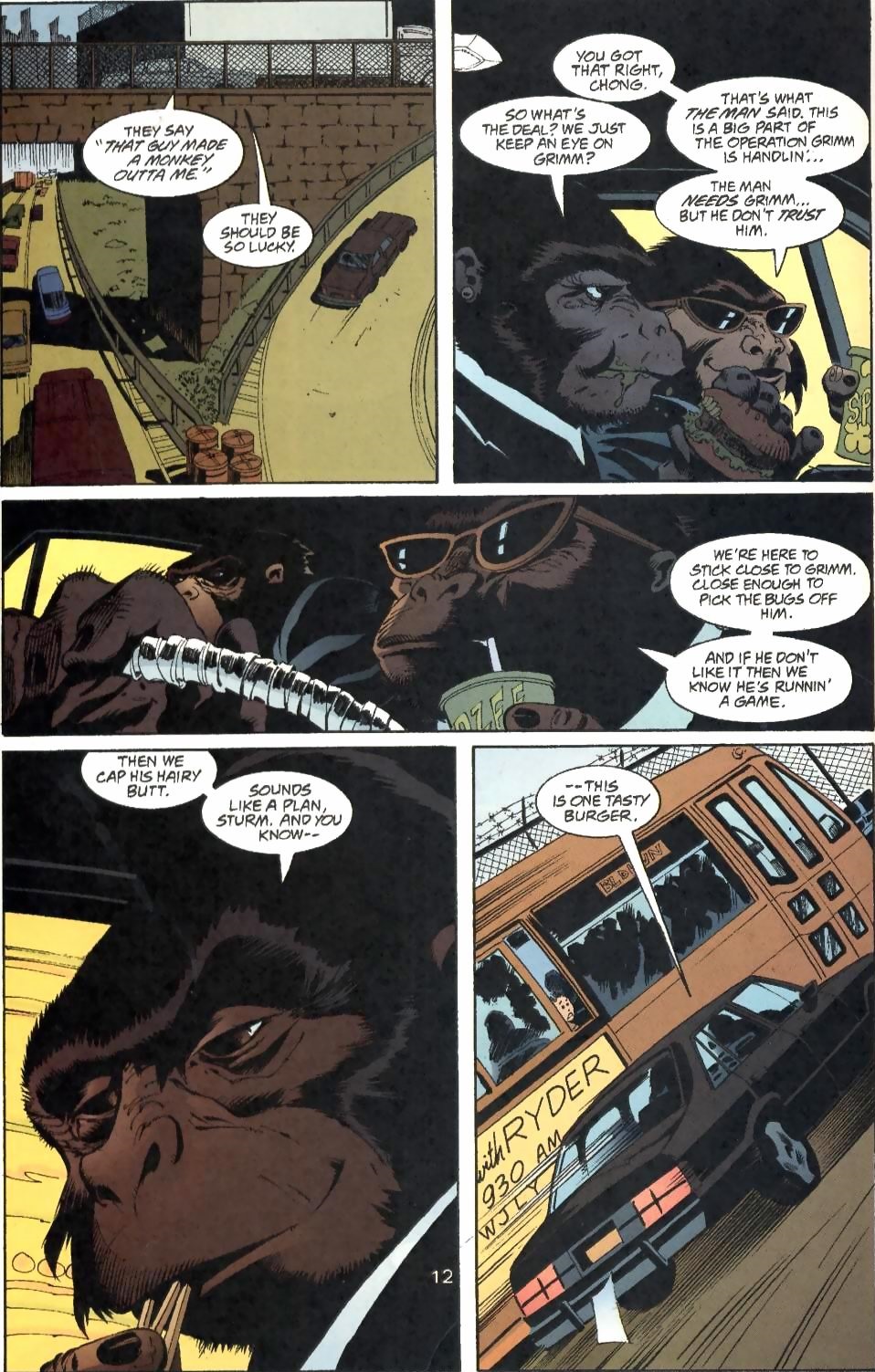

Speaking of Tarantino, Dixon penned one of the weirdest riffs on Pulp Fiction, starring a couple of talking gorillas:

Batman Annual #23

Batman Annual #23

(Naturally, there was also a Planet of the Apes joke in this issue.)

While Chuck Dixon’s cinephilia is probably shared by most of his colleagues, the same doesn’t necessarily hold true for his political leanings. Dixon is an increasingly outspoken conservative who seems to support Donald Trump (even though I assume there is something tongue-in-cheek about the fact that he wrote a Trump’s Space Force comic).

I’ve seen him downplay the influence ideology has on his comics because they’re allegedly not political, in the sense that they deal with escapist fiction about heroes with broad, universal values. I’m quite wary of this understanding of politics, but even if you go with a relatively narrow definition you have to admit Dixon has tackled a number of hot topics, especially in Robin, which dramatized teen issues such as gun violence, sexual assault, school bullying, unwanted pregnancy, and alcoholism.

What you can argue – and many have – is that Dixon tends to respect each franchise’s history and themes, hence he has written Batman stories that are ultimately geared against the death penalty or in favor of gun control, despite being a member of the NRA…

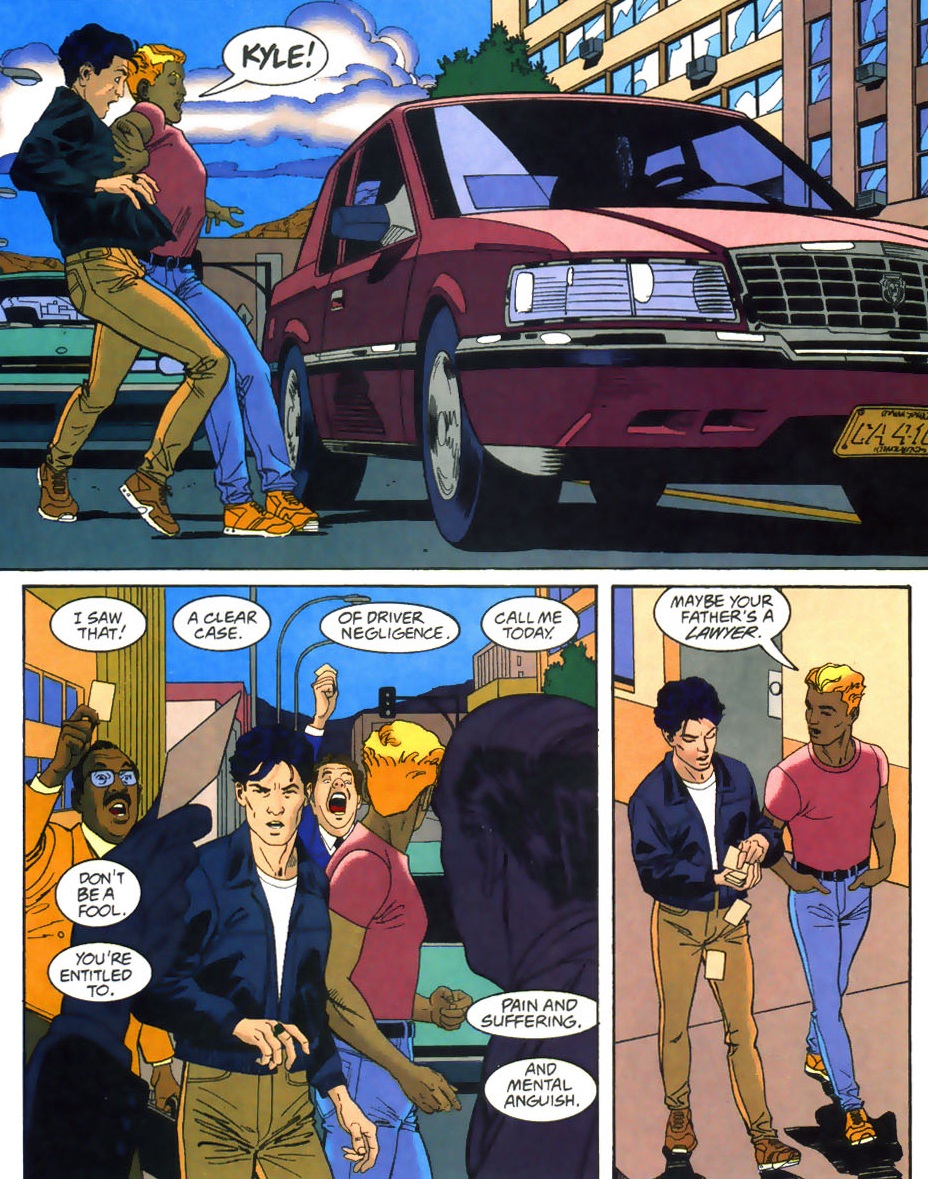

Robin (v4) #43

Robin (v4) #43

There is no doubt that the Chuck Dixon who showed up for work at DC was first and foremost a storyteller, not a polemicist. For the most part, his scripts served the narrative without preaching. After all, despite his flair for gung-ho action, Dixon has always understood that moral complexity and nuance are the grist of compelling drama. You can see this, for instance, in ‘The Villain’ (Birds of Prey #7), where Black Canary tries to save an exiled Latin American dictator, only to realize that the world of international politics can be way more complicated than good guys versus bad guys.

Overall, I’d say his comics aren’t likely to upset liberal Batman fans, except for those who find it hard to engage with work on its own terms when it’s done by creators who have said or done problematic things – an attitude that does seem to be spreading, as seen in the recent controversy over Roman Polanski’s An Officer and a Spy (although in that case the alternative is pretty easy: if you’re interested in the story but don’t want to watch the film because of its director, get your hands on Robert Harris’ original novel, which is a fine read).

Even when Dixon occasionally indulged in right-wing tropes such as mobbed up unions, ethnic gangs, and eagerly pro-abortion planned parenthood counsellors, or when he took small jabs at the Democrats (for example, in Detective Comics #708 and Birds of Prey: Revolution), these didn’t distract from the main story.

Robin (v4) #94

Robin (v4) #94

Mostly, though, I think what makes it work isn’t that Dixon kept his politics out of comics, but that he integrated them in smooth, satisfying ways that didn’t feel forced. While he played along with the progressive elements of the Batman narrative (his Caped Crusader kept going out of his way to save the Joker’s life), he also embraced its more reactionary side (like the constant indictment of the system’s leniency towards criminals). He wisely left the most anti-PC jabs for Harvey Bullock. And when his Robin expressed a concern with traditional family values (while talking to Spoiler about the possibility of her becoming a single mother) or his Batman showed respect and admiration for religious faith, these scenes didn’t come across as ham-fisted. They didn’t clash with the characters or the stories…

For example, check out this nice little moment after Gotham City was devastated by an earthquake:

Detective Comics #724

Detective Comics #724

(The one exception is the underwhelming one-shot The Chalice, a contrived Christian tale in which it turns out Bruce Wayne descends from a long line of protectors of the Holy Grail… Even the usual cameos feel clunky in this one. I wouldn’t mind a Batman version of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, but sadly The Chalice isn’t it.)

I’ll make a similar case for Chuck Dixon’s underrated forays into slapstick: it’s not that they were apolitical, it’s that the way they incorporated politics was often pretty funny. The most remarkable example is ‘Desolation Again’ (Green Arrow #110), in which the latest versions of Green Lantern and Green Arrow went looking for the former’s father in the town of Desolation, where their predecessors had fought for social justice in defense of exploited miners back in 1970 (in the classic Green Lantern #77, by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams). The joke was that they now found an affluent Desolation, which had become ‘the lawsuit capital of America.’ As a local explained to them: ‘Lots of folks in town sued the mining company and got major cash rewards. Almost everybody in the county hit the litigation jackpot.’ Suing each other had thus become the basis of the local economy.

Green Arrow (v2) #110

Green Arrow (v2) #110

Mocking a culture of excessive litigation is typically associated with the Right – and there is definitely something provocative about doing it in a story that explicitly calls back to one of the most famous leftist runs in the history of comic books. Yet the caricature is so amusingly over-the-top that I can’t help laughing along!

The same goes for several gags in Chuck Dixon’s more Batman-related work…

Birds of Prey #10

Birds of Prey #10

(You can see why Dixon went on to write Simpsons comics!)

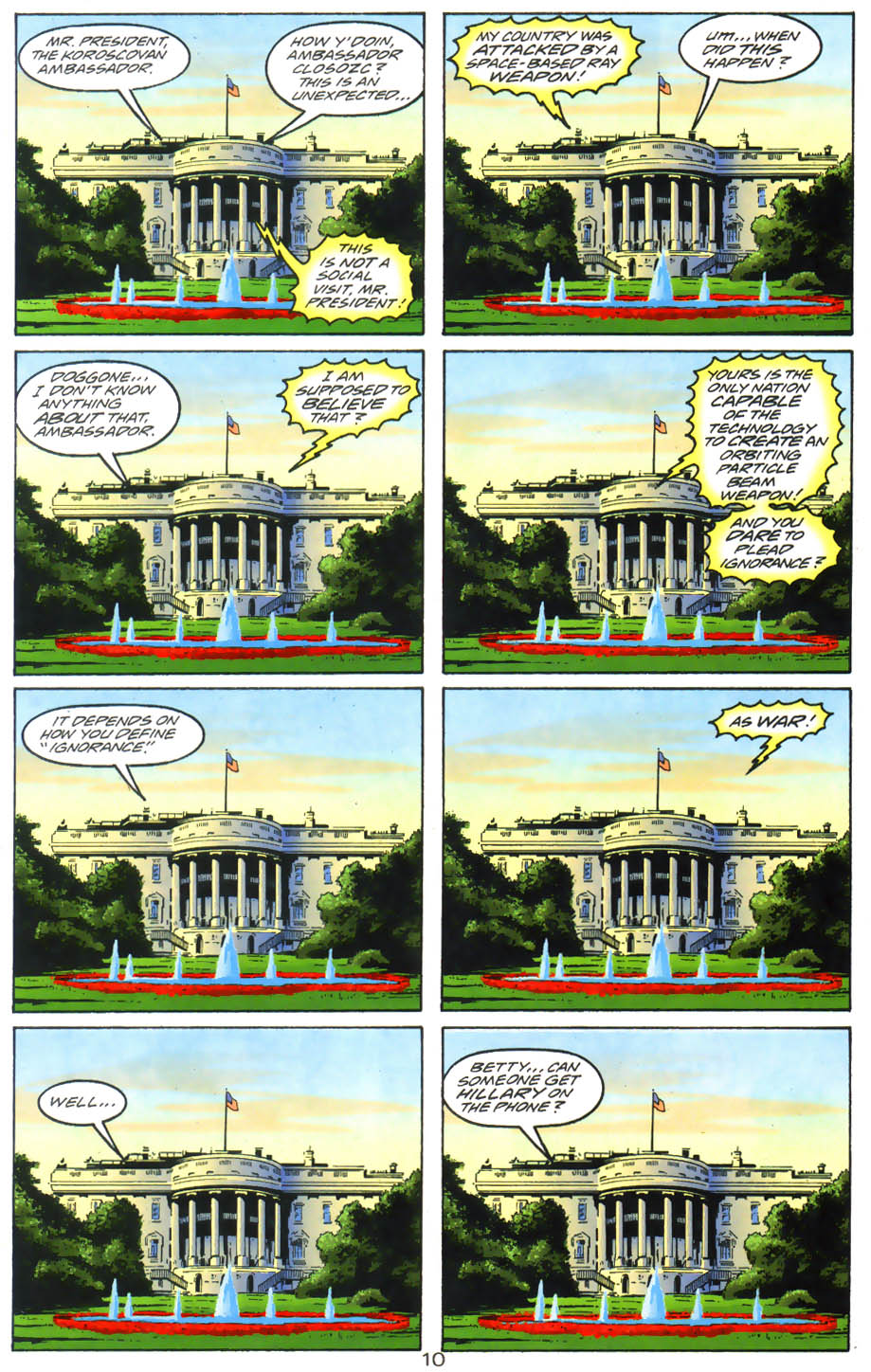

The one area where Chuck Dixon felt comfortable addressing politics more thoroughly was in the international arena – in part because his views in this field weren’t as out-of-step with the mainstream, and in part because there are so many fictitious countries in the DCU that you have a pretty wide leeway to play around. Most notably, Birds of Prey starred a globetrotting Black Canary who kept travelling to places with names like Markovia and Koroscova. There was even an arc set against the background of a Middle Eastern crisis (#15-17) which revisited an old storyline about the Joker being a former diplomat from Qurac (originally Iran).

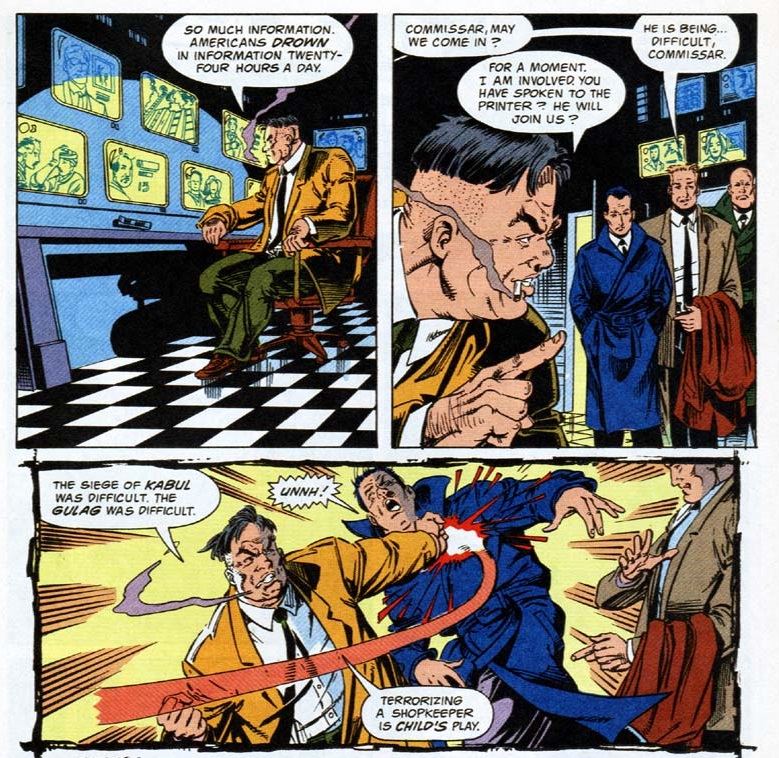

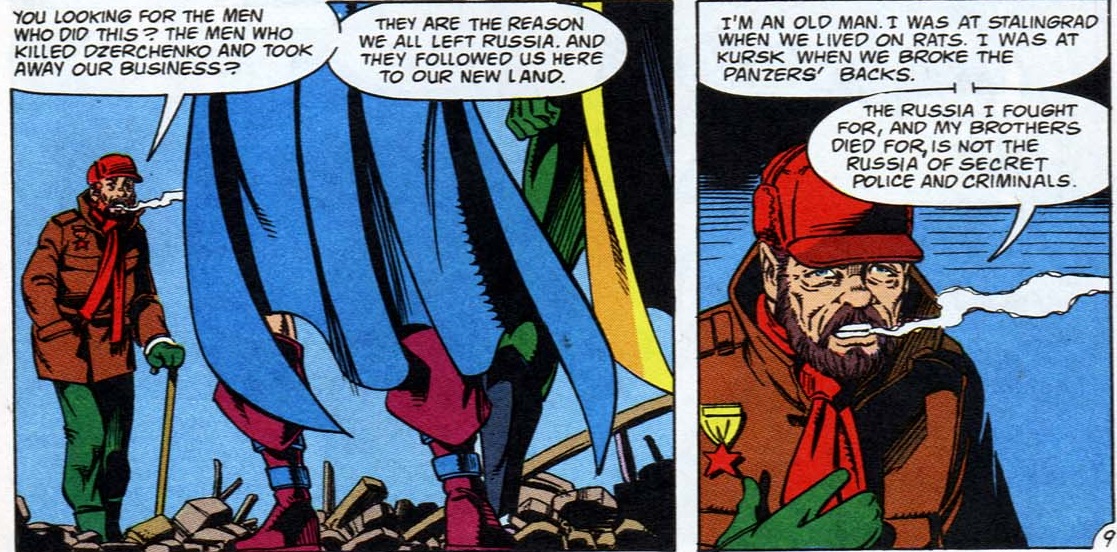

Several of Dixon’s comics engaged with the fallout from the breakdown of the Soviet Union, going back to the 1993 mini-series Robin: Cry of the Huntress, which introduced Ariana Dzerchenko, a teen of Ukrainian descent who went on to become Tim Drake’s girlfriend. Her father owned a printshop in Little Odessa, Gotham’s Russian neighborhood, and was attacked by the Commissar, a mobster who wanted him to forge EU money before the original currency actually went into circulation!

Robin (v3) #1

Robin (v3) #1

The Commissar was part of The Hammer – the USSR’s secret services branch that had created the master assassin KGBeast. The Hammer had gone criminal after the Soviet collapse and was now involved in heroin smuggling, gambling, extortion, and murder for hire.

Robin (v3) #3

Robin (v3) #3

Indeed, Chuck Dixon’s comics typically displayed quite a cynical view of the messy post-Soviet transition – like in 1994, when he brought together a group of ex-communists-turned-criminals:

Robin (v4) #12

Robin (v4) #12

This group went on to threaten Gotham City with a small nuke in the thrilling crossover ‘Troika’ (Batman #515, Shadow of the Bat #35, Detective Comics #682, Robin #14), half of which was written by Dixon. It turned out they all had different views on how to adapt (or not) to capitalism and ended up spending almost as much time double-crossing each other as fighting the Dynamic Duo!

Dixon often took his characters to the post-Soviet side of the world. For example, in the neat mini-series Birds of Prey: Manhunt, Black Canary chased an ex-KGB agent into a criminal hideout in Kazakhstan (also a setting in Bane: Conquest). On the pages of Catwoman, the titular thief was hired by the US government to steal the crown of Prinz Willem Augen Kapreallian, heir to the no longer existent throne of Transbelvia, ‘one of the micro-republics left over when the Soviet Union broke up.’ The Americans hoped to return the crown to the Transbelvian Cultural Ministry and secure at least one ally in the former Eastern Bloc, but, after many twists and turns, the prince captured Catwoman and tried to force her to marry him, culminating in a ceremony bursting with mayhem, as the bride, the groom, US spies, and Corsican mobsters all shot at each other (Catwoman #15-18). Later, Robin travelled to Transbelvia as well, trying to prevent a military conflict (Robin #50-52), and so did Black Canary, who found herself in the DC version of the Yugoslav Wars (Birds of Prey #18).

Some of these comics can get pretty grim (not unlike Dixon’s similarly themed The Punisher: River of Blood), but you can also find in them Dixon’s acerbic wit. In particular, he got a fair bit of mileage out the playful clash of cultures and ideologies…