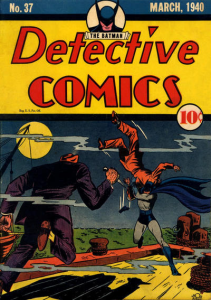

If, like me, you dig pretty much everything noirish (even if it’s a highly derivative mash-up of familiar tropes, a weirdly pretentious cheapie about an incompetent hitman, a sleazy erotic thriller with contradictory gender politics, or a mystical, sluggishly paced Bhutanese mystery), surely some of the appeal Batman comics hold for you is the remarkable influence of hardboiled pulp fiction and film noir.

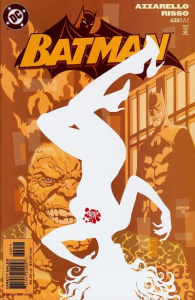

This influence was clear from the very first stories and, while the Dark Knight went on to have many other kinds of adventures, several writers and artists have kept the genre connection alive (most notably Frank Miller, Bruce Timm, and Brian Azzarello). Apart from Elseworlds pastiches like Nine Lives and Gotham Noir, you can find blatant homages to all those hard-hitting, convoluted tales of betrayal and murder – written in a scathing staccato rhythm oozing with male gaze, a sense of doom, and atmospheric slang, filled with slick mobsters, femmes fatales, tough guys in search of justice, and desperate protagonists haunted by their past – in gritty comics such as Batman: Year One, The Long Halloween, Broken City, Gordon’s Law, and City of Crime.

Yet perhaps you’re coming at it from the opposite direction. Perhaps you gained a taste for these elements through the comics and are now wondering about having a look at the original source. In that case, you are in for a ride, my friend! A couple of years ago, I suggested a bunch of film noir gems but, if you want to engage with the genre at its best, make sure you also pick up these three quintessential novels:

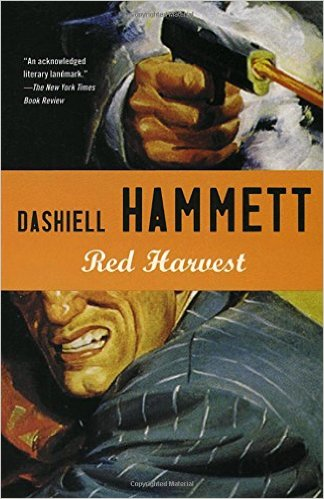

RED HARVEST

(Dashiell Hammett, 1929)

“I first heard Personville called Poisonville by a red-haired mucker named Hickey Dewey in the Big Ship in Butte. He also called his shirt a shoit. I didn’t think anything of what he had done to the city’s name. Later I heard men who could manage their r’s give it the same pronunciation. I still didn’t see anything in it but the meaningless sort of humor that used to make richardsnary the thieves’ word for dictionary. A few years later I went to Personville and learned better.”

While working a case in a city that seriously rubs him the wrong way, an unnamed private investigator (an operative of the Continental Detective Agency) decides to declare war on crime by manipulating a dozen gangsters into killing each other. Less of a pure detective tale than Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, this is essentially a chain of interconnected mysteries, as the book keeps providing new twists almost until the final paragraph.

Hammett’s anti-hero spins this sordid yarn like a furious scriptwriter on a tight deadline, keeping most descriptions on the surface while letting you work out each character’s hidden agenda – they all have one! – based on their external actions and dialogue. He gives you just enough to feel the reek of smoke and sleaze all around. You can also sense the narrator gradually getting carried away by his self-imposed mission.

“This damned burg’s getting me. If I don’t get away soon I’ll be going blood-simple like the natives.”

The result is one hell of a page-turner, with quite a cinematic flair… No wonder Red Harvest – mixed with the also-cool-but-not-as-cool The Glass Key – served as inspiration for the phenomenal movies Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars, and Miller’s Crossing. (The quote above also inspired the title of the Coen brothers’ neo-noir Blood Simple.)

Furthermore, there is a lot of Gotham City in Personville (aka ‘Poisonville’) with its gaudy buildings, overwhelming corruption, and endless supply of devious bastards.

THE LONG GOODBYE

(Raymond Chandler, 1953)

“The first time I laid eyes on Terry Lennox he was drunk in a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith outside the terrace of The Dancers. The parking lot attendant had brought the car out and he was still holding the door open because Terry Lennox’s left foot was still dangling outside, as if he had forgotten he had one. He had a young-looking face but his hair was bone white. You could tell by his eyes that he was plastered to the hairline, but otherwise he looked like any other nice young guy in a dinner jacket who had been spending too much money in a joint that exists for that purpose and no other.

There was a girl beside him. Her hair was a lovely shade of dark red and she had a distant smile on her lips and over her shoulders she had a blue mink that almost made the Rolls-Royce look like just another automobile. It didn’t quite. Nothing can.”

The premise of The Long Goodbye involves the sardonic (if principled) private eye Phillip Marlowe trying to clear the name of his friend Terry Lennox, who seems to have murdered his wife. However, once again the labyrinthine plot keeps on spinning in surprising directions until the bitter end.

Raymond Chandler’s prose is a joy to read. He’s a master of witty turns of phrase and logical yet unexpected punchlines, with a sharp eye for detail (especially when it comes to capturing the decadence of Los Angeles). This is one of his most ‘literary’ novels, packed with beautiful descriptions, intriguing characterization, some social commentary, and a genuinely melancholic atmosphere drenched in hopeless loneliness and alcoholism. That said, Chandler doesn’t stray too far from his pulp origins: he still gives readers plenty of violence and hardboiled one-liners. While not as seedy as The Big Sleep, this is one mean read.

“I’m a licensed private investigator and have been for quite a while. I’m a lone wolf, unmarried, getting middle-aged, and not rich. I’ve been in jail more than once and I don’t do divorce business. I like liquor and women and chess and a few other things. The cops don’t like me too well, but I know a couple I get along with. I’m a native son, born in Santa Rosa, both parents dead, no brothers or sisters, and when I get knocked off in a dark alley sometime, if it happens, as it could to anyone in my business, nobody will feel that the bottom has dropped out of his or her life.”

Twenty years later, Robert Altman did a bizarre film adaptation that hugely simplified the story (although adding an extra knockout twist at the end!) while transposing it from the noirish 1950s to the New Age 1970s. If nothing else, the picture is worth watching just for all the little quirks, like the fact that Elliott Gould of all people is cast as Marlowe or the fact that every tune in the soundtrack is a variation of the same song.

THE HUNTER

(Richard Stark, 1962)

“When a fresh-faced guy in a Chevy offered him a lift, Parker told him to go to hell. The guy said, “Screw you, buddy,” yanked his Chevy back into the stream of traffic, and roared on down to the toolbooths. Parker spat in the right-hand lane, lit his last cigarette, and walked across the George Washington Bridge.”

Sure, we all love watching rugged detectives played by Humphrey Bogart and Alan Ladd struggling to do what’s right in an unfair world, but a great allure of film noir is also the sub-genre of movies where you find yourself rooting for hardened criminals who are just trying to pull a job in as professional a manner as possible (Jules Dassin’s Rififi, Paul Wendkos’ The Burglar, George Sherman’s Larceny). Under the pseudonym Richard Stark, writer Donald E. Westlake gave us his share of this type of stories in dozens of deliciously nasty thrillers about Parker, a ruthless freelance robber with big hands and a craftsmanlike, take-no-shit attitude.

In the series’ first entry, The Hunter, we meet Parker after he has been double-crossed and left for dead. We follow him – and, in the mid-section, one of his prey – as he methodically tortures and/or kills his way up the mob-like organization known as the Outfit in order to get his revenge… and his money back. Unlike the two books I mentioned above, The Hunter is written in the third person, but the gripping, unsentimental style actually mirrors Parker’s personality.

“It was his belt buckle that saved him. Her first shot had hit the buckle, mashing it into his flesh. The gun had jumped in her hand, the next five shots all going over his falling body and into the wood of the door. But she’d fired six shots at him, and she’d seen him fall, and she couldn’t believe that he was anything but dead.”

As others have pointed out, one of the things that makes The Hunter so enduring is that, even though it starts out as a personal revenge quest, it ultimately turns into a confrontation between a solo entrepreneur and a big corporation. The novel efficiently sets up a whole underground world of organized crime, with strict rules, specialized hotels, and an intriguing sense of community (not unlike the recent John Wick movies). It’s also a tight little beast, the action unfolding in a way that is as straightforward and relentless as Parker himself.

This book has been loosely adapted to the big screen at least three times (with the titles Point Blank, Full Contact, and Payback) and there is a gorgeous graphic novel rendition as well. Moreover, with its skill at delivering taut dialogue and keen heist plots, the Parker series was an obvious influence on the Catwoman comics of Chuck Dixon and Darwyn Cooke.

NEXT: Batman collections.