The folks at Dead Reckoning sent a copy of Garth Ennis’ and Carlos Ezquerra’s The Tankies for me to review, so I figured it would be fun to put the book into context by discussing it together with other collections of war comics. After all, military fiction has come a long way since its foundational role in the medium as World War II propaganda and, as we are living in the Golden Age of Reprints, readers can now assess how different creators have tackled this genre in various ways throughout the decades.

CORPSE ON THE IMJIN! AND OTHER STORIES

Before going on to mock US popular culture in Mad, Harvey Kurtzman memorably desacralized another key American institution – war – on the pages of two iconic EC anthology series he both edited and wrote: Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat. What’s more, he did it during the Korean War, when most other publishers were spouting hyperpatriotic yarns and the comic-book industry (especially EC) was under the double threat of McCarthyism and the large-scale anti-comics panic of the early 1950s. Fantagraphics’ Corpse on the Imjin! and Other Stories collects dozens of those Kurtzman comics, which he approached in a much grimmer and more serious-minded tone than Mad – according to R.C. Harvey’s introduction, he was emulating Charles Biro’s storytelling in the Lev Gleason crime books (Crime Does Not Pay and Crime and Punishment), with its fact-based ‘hard-edged documentary style.’

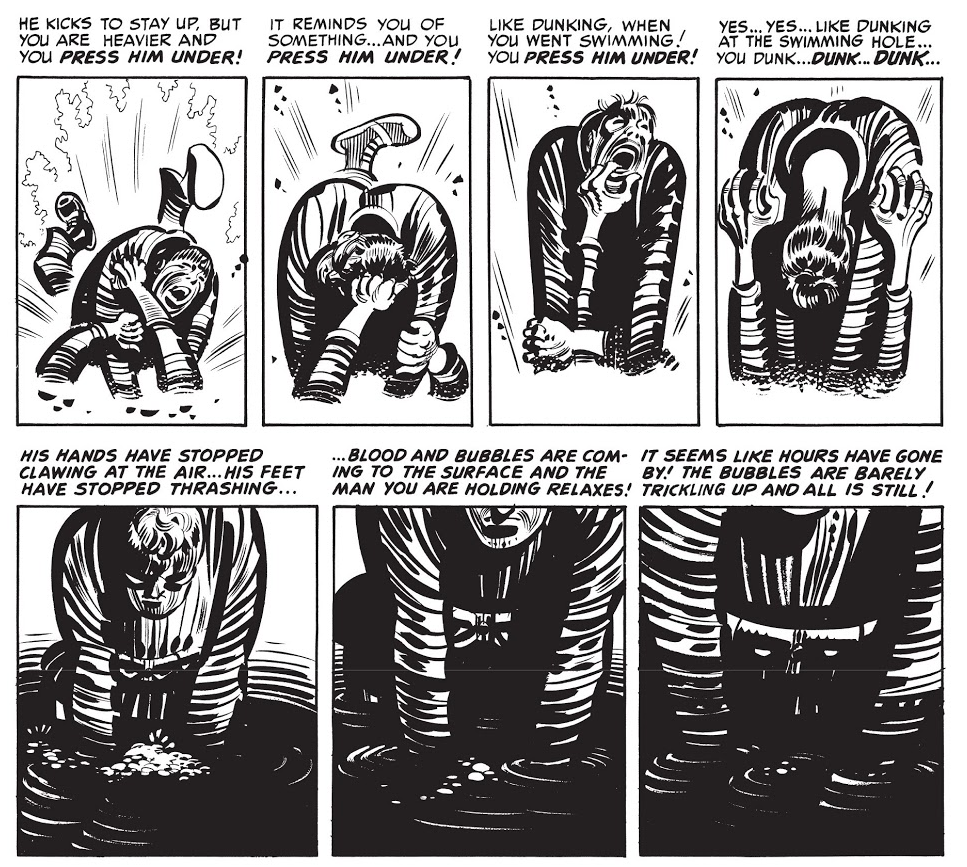

A brilliant cartoonist, Harvey Kurtzman also drew a bunch of these tales, here reprinted in a stark black & white full of shadowy negative space and proto-noir atmosphere (except for the covers, which keep Marie Severin’s vivid original colors). Kurtzman’s delightfully exaggerated, rubbery figure work makes for quite a striking juxtaposition with the vicious content, combining thoughtful layouts and a sense of well-researched authenticity with highly expressionistic visuals. There are a few early experiments, including a brutal take on colonialism (‘Conquest’) and a couple of straightforward adventures about pirates and criminals in exotic lands, still privileging excitement over any political message beyond a general contempt for ruthless greed. For the most part, though, this is one of the greatest collections of war comics ever – the titular story, in particular, is a masterpiece of the medium, unflinchingly capturing the agony of taking a human life with your bare hands (as shown above).

Reacting against the way other comics mobilized young readers by romanticizing combat and dehumanizing the enemy, Kurtzman made a point of deglamorizing warfare and highlighting how symmetrical – and immoral – were many of the actions of soldiers on the two sides. A running motif is the notion that a life is a life and, even if you have to kill in some circumstances, you shouldn’t enjoy doing it… The impact of the glorification of war on impressionable kids is directly fictionalized in this collection’s final story (‘Memphis!’), with a character concluding that grown-ups ‘ain’t got no more sense ‘bout how serious war is’ than children. And while Kurtzman worried about other comics’ influence, the authorities’ worried about his own: Grant Geissman’s The History of EC Comics quotes fascinating documents from the files of the FBI, which closely monitored Kurtzman and, in 1952, actually consulted the Department of Justice over whether these comics constituted a violation of the sedition statutes. After all, in the words of a confidential informant: ‘Some of the material is detrimental to the morale of the combat soldiers and emphasizes the horrors, hardships, and futility of war.’

That said, the book doesn’t hit you on the head with the same message over and over. The stories touch on different aspects of conflict and they even contain a variety of perspectives: for every preachy (‘And now that your bodies are growing cold and your limbs are stiffening, how do you like death, Li and Abner? How do you like death, humanity?’), you get a gruffier, Sam Fuller-esque outing. In fact, these comics aren’t all necessarily anti-war – or even anti-Korean War. It’s just that they try to problematize and nuance the era’s racist jingoism by humanizing both the Americans (not supermen) and the Koreans (not supervillains). For instance, ‘Contact!’ takes a clear stance against the use of white supremacy to justify giddily slaughtering Asians, but the closing narration still sounds awkwardly naïve (‘And remember, if we believe in good, we can’t go wrong!’) – Kurtzman himself calls that line ‘dreadful’ in a 1982 interview collected at the end of the book!

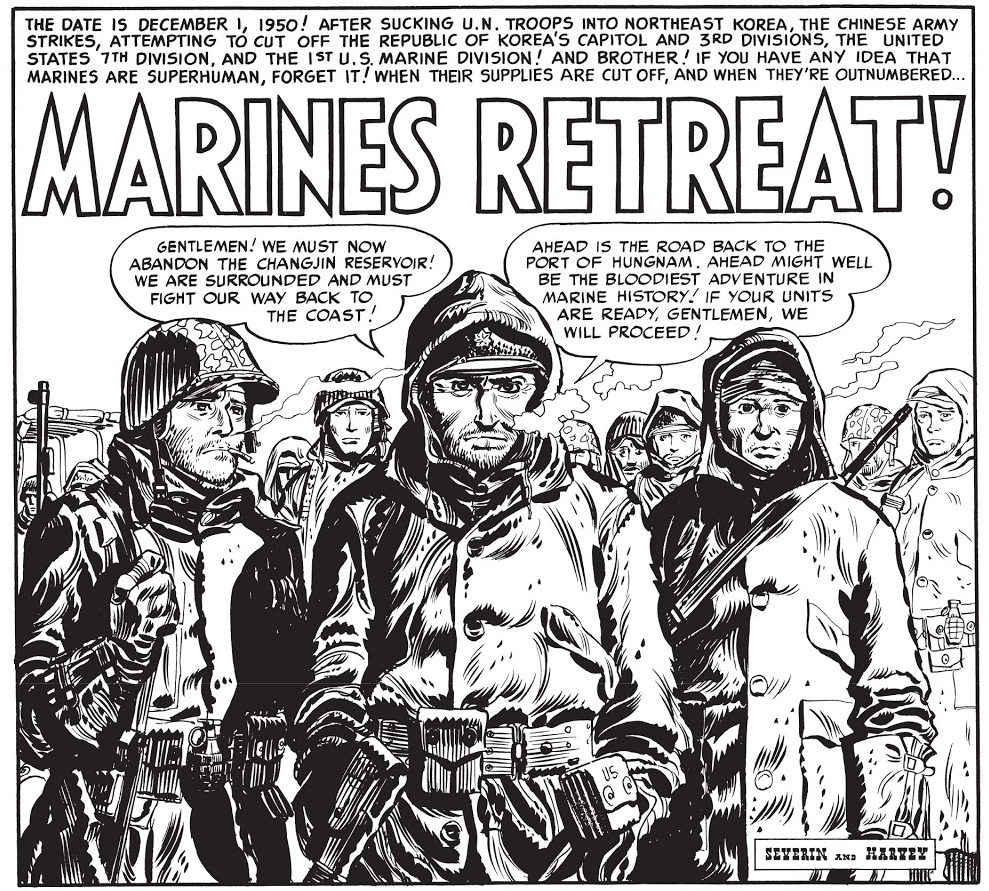

The panel above was pencilled by John Severin, one of a core team of acclaimed artists who illustrated Harvey Kurtzman’s scripts – and meticulous layouts – at the time and whose work is collected in the second half of the book. Other names include Alex Toth, Russ Heath, Dave Berg, Gene Colan, Ric Estrada, Johnny Craig, Joe Kubert, and Reed Crandall. Like Severin, most of them had a much more realistic style than Kurtzman, so the obsession with historical detail he demanded shines through even more in their work (not to mention the fact that many of them were war veterans themselves and therefore familiar with a lot of what they were drawing). This section is quite diverse in terms of content as well, with tales (they’re more like vignettes, really) about naval battles, trenches, and aircraft (Toth’s specialty) spreading to WWII, WWI, the Spanish-American War, the Civil War, and even the American Revolutionary War (Kubert’s harrowing ‘Bonhomme Richard!’).

As if all this wasn’t enough, Corpse on the Imjin! and Other Stories also contains insightful essays by scholar Jared Gardner, cartoonist Frank Stack, and EC experts S.C. Ringgenberg and Ted White. It’s a must-read for any fan of classic comics and/or military fiction.

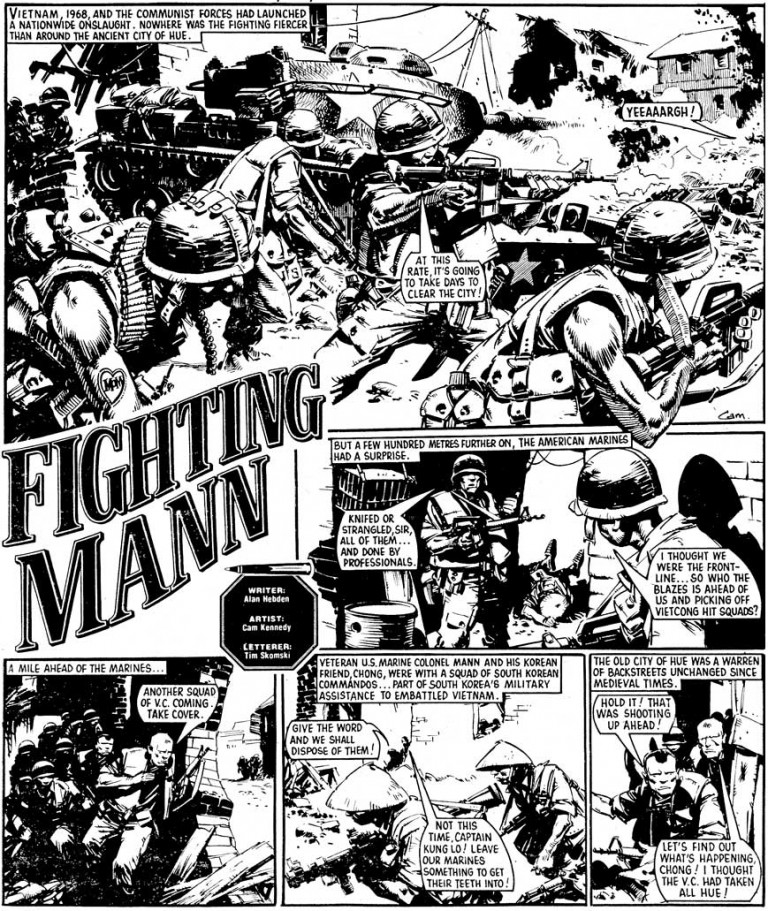

BATTLE CLASSICS: FIGHTING MANN * WAR DOG

Although they share a fondness for both caustic humor and dead-serious military fiction, Garth Ennis clearly owes less to Harvey Kurtzman than to the revival of war comics in the UK in the mid-to-late 1970s on the pages of Battle Picture Weekly, the anthology launched by the awesome duo of Pat Mills and John Wagner. Much of it consisted of violent thrillers with morally questionable anti-heroes, often illustrated by artists such as Cam Kennedy and Carlos Ezquerra, so it’s not difficult to spot the influence. In fact, Ennis himself has been quite open about it, even curating a selection of reprints of his favorite tales from this era, titled Battle Classics, whose second volume compiles the serials Fighting Mann and War Dog.

Originally serialized in 1980-1981, Fighting Mann is a brisk, full-throttle action yarn about Walter Mann, a retired US marine colonel who goes to Vietnam in 1967 to investigate the mysterious disappearance of his navy pilot son. Mann finds out the disappearance is connected to something called ‘the Laotian problem’ and gradually gets involved in a web of cold war intrigue, but he spends most of the time struggling for his life, which tends to get threatened on every third page, as practically everyone seems out to get him, from the Vietnamese (North and South) to the CIA and the Khmer Rouge, among many others…

This is war as grist for kickass adventure, tastelessly exploiting a real-world conflict for cheap thrills, as writer Alan Hebden seems less interested in questioning or defending the US intervention in Vietnam than in supplying an endless stream of explosions, cliffhangers, and spy games. Still, you get a tour through various aspects and players of the Southeast Asian war zone – including historical episodes such as the Tet Offensive or the fire aboard the USS Forrestal – and thus a hint of its geopolitical complexity and massive carnage. I’m not saying you get a balanced, equidistant picture, since the Vietnamese do generally come off worse than the Americans (in turn, Mann appears to get along fine with a Russian KGB agent), but ultimately nobody is particularly likable on either side anyway, except perhaps for Chong, a South Korean who fought alongside Mann in the Korean War and whose resourcefulness and loyalty make him a key ally. Hebden had a knack for these cynical narratives (he also wrote Death Squad, whose leads belonged to a Wehrmacht punishment battalion in WWII’s Eastern Front), brazenly foregoing any proselytizing – or even any deep characterization – in the name of relentless forward momentum. Mann himself is a pulsating storytelling engine, moving with determination and macho stoicism through a jungle of armed characters and battle situations, at first barely pausing to contemplate the implications of what is happening around him, yet eventually getting wrapped up in the conflict.

If there is never a boring moment in this comic, that’s also because of Cam Kennedy’s top-notch artwork. Kennedy’s style combines meticulous, quasi-photographic renditions – especially of weapons and aircraft – with a lot of evocative brushstrokes and hatching, his sharp inks making the most out of the format (unlike the stories in Corpse on the Imjin!, these were originally published in black & white). Sometimes a few strategically placed lines are enough for us to conjure up a sprawling landscape and assorted vegetation in our mind. The result is nothing short of stunning.

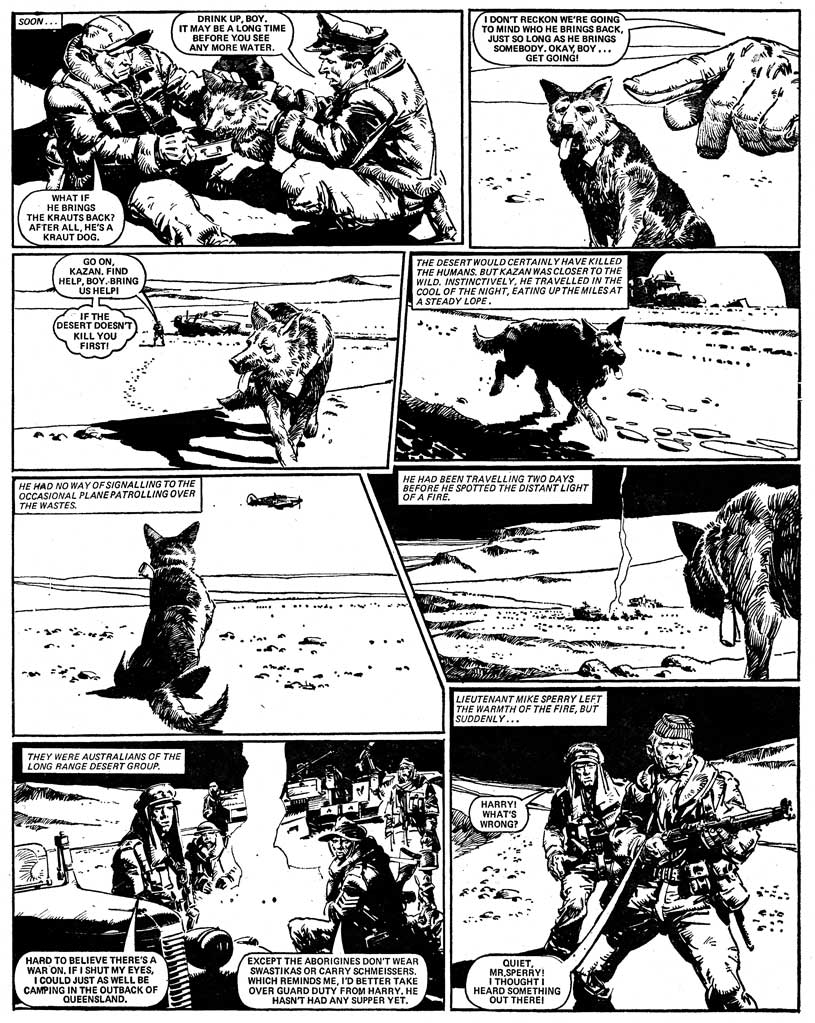

The last part of the book collects 1979’s War Dog, about a German Shepherd trained by the Lufwaffe who ends up travelling through several WWII hot spots. Imagine a more brutal version of Lassie, set against one of the most horrible backdrops in contemporary history, approached with a fairly naturalistic tone up until the ferocious finale… Alan Hedben writes it in the same action-driven, unsentimental style as Fighting Mann, using another moving protagonist to guide readers through different regions and players in an (even more) international conflict. Also, he joins complicit artists who privilege gritty visuals and accuracy over melodramatics: first Mike Western and then, once again, the reliable Cam Kennedy (who did the page above).

Titan really did a bang-up job with Battle Classics. A hardback collection with thick paper and extra-large size, the book lets the artwork breathe, inviting you to contemplate each carefully composed sequence in all its detail and virtuoso draftsmanship, the original pages (which apparently were in a wretched state) wonderfully restored by Moose Harris. You also get interesting text pieces by Garth Ennis, which I recommend reading after the respective comics, to avoid spoilers.

THE TANKIES

This brings us to The Tankies, which collects a trio of mini-series first published by Dynamite in 2009-2013, part of the Battlefields meta-series. These had been collected separately before, but they do belong together, as they follow the same rugged tank commander, Stiles, through World War II and the Korean War, in charge of a Churchill, then a Firefly, and then a Centurion. An imprint of the Naval Institute Press, Dead Reckoning has been building a solid catalog of war comics (especially older works and translations), so it makes sense for them to get some of Garth Ennis’ stuff in there, even if these particular series are hardly modern classics… Perhaps DR republished them as a tribute to Carlos Ezquerra, who died just a few years ago, but in that case we deserved some kind of essay about his artwork rather than just a reprint of his his rough sketches and character designs (although it’s quite cool to compare them to the versions inked by his son, Hector).

When these tales originally came out, Ennis had already become a superstar of realistic WWII comics. You could see him stretch his writing muscles in other earlier Battlefields minis – ‘Night Witches’ and ‘Dear Billy’ – but ‘The Tankies’ was clearly a looser project, with less investment in characterization (I dare anyone to distinguish the personality of more than a couple of crewmen) and plotting (most chapter breaks feel random and half-hearted). Alternatively, this can perhaps be considered the more grounded of the bunch, with its generally unremarkable cast and disjointed narrative amounting to a semi-documentary glimpse into life on the battlefront. In any case, what you do get – and for some of us this can be enough – is a lot of historical and technical detail, placing you in the middle of the action while capturing both the fascinating logistics and the sense of desperation of tank battles in these specific war zones.

The result is certainly not for all tastes – and not just because of the hardcore language and gore. In addition to the jargon-heavy dialogue, Stiles has a painfully thick Newcastle accent, so you can only get much of what he’s saying by reading those bits out loud, phonetically (this wouldn’t be so bad if not for the fact that some of the action in the middle is told rather than shown, making it a very text-driven work…). Moreover, while Carlos Ezquerra draws on decades of experience doing WWII comics through his typical mix of unattractive faces and intuitive storytelling, his art doesn’t exactly benefit from Tony Aviña’s bright colors, which feel way too clean for such dirty settings (even though the palette appears suitably flatter in this edition compared to the original comics, if I’m not mistaken).

Still, there are rewarding moments for those willing to plough through. Ennis has fun playing with the petty rivalries within the crew, especially between the Geordie corporal and the Cockney gunner. Plus, there’s the obligatory gallows humor:

Putting The Tankies into a larger context made this an engaging reread. Although the book conveys respect for many of the men on the ground, including the Germans, it’s less interested in humanizing the Koreans than some of Kurtzman’s tales. In turn, it also rejects the more conventional adventure beats that punctuate Hedben’s scripts. Ennis doesn’t challenge the need for war, yet he also doesn’t shy away from its grisly reality – and neither does Carlos Ezquerra, whose depictions of combat are anything but romantic. Like Ezquerra’s sketchbook, Ennis’ thought-provoking, historically informative afterword had been previously published in The Complete Battlefields, so I was disappointed by the lack of new material (Michael J. Vassallo’s introduction was one of the high points of Dead Reckoning’s Atlas at War!), but this remains a worthy collection for any military history buffs out there who haven’t got these comics already – it should fit nicely on the shelf next to the other two books.

Above all, I cannot help considering The Tankies within Garth Ennis’ trajectory. Having grown up in Northern Ireland in the 1970s/80s, part of this writer’s success has always been to take his influences from the creative explosion in the British comics from his childhood and translate them into the American market. For instance, you can see a lot of Judge Dredd in his Punisher and one of Hitman’s arcs was a direct homage to 2000 AD’s ‘Flesh.’ Likewise, Ennis’ war comics feel like clear successors to the likes of Battle, albeit often more sophisticated and less gimmicky… The brilliant tank yarn ‘Johann’s Tiger’ (whose protagonist gets a passing mention in The Tankies) was no doubt inspired by the serial Hellman of Hammer Force. While not as memorable as ‘Johann’s Tiger,’ The Tankies blatantly fits into this trajectory as well, as its abundant slang, sardonic voice, and men-on-a-mission framework wouldn’t look out of place on the pages that first formed Ennis’ sensibility (except for the amount of swearing).

Kelly Kanayama has written insightfully about this lineage: ‘a typical lead character in a 1970s British war comic and a typical Ennis protagonist are both hardbitten sociopolitical underdogs who adhere to semi-cynical but nonetheless strict moral codes formed by some kind of trauma. But the connections between British war comics and Ennis’ work extend beyond character development to encompass the worlds in which these characters operate. War can be described, albeit reductively, as unrestrained violence generated by male-dominated sociopolitical structures and perpetuated in the blood of Good Men (“the real heroes are,” etc.) – and few Ennis comics could exist without the dissonance between these two, asking us as they do to decry the former while giving our hearts to the latter.’

The Tankies thus transports readers not just to the muddy countryside of French, German, and Korean battlefields in the 1940s/50s, but also to a later era when British creators channeled into boys’ comics the war stories they had heard from their parents, implicitly pitting them against the armed conflicts haunting their own generation (including in Northern Ireland)… just as Ennis wrote these comics under the specter of a decade of disgraced military interventions in the Middle East.