This weekend, I too went to see Dune: Part One, Denis Villeneuve’s majestic – if largely monochromatic and, despite the heat, coldly assembled – adaptation of the first half of the first book of Frank Herbert’s heady space opera. Given my fondness for political thrillers and my fascination with international relations, I felt right at home in its web of palace intrigue and imperial maneuvers, even if this is the worst kind of understanding of IR…

Even more than in his other visually stunning forays into science fiction – Enemy (a weirdly arachnid adaptation of José Saramago’s Kafkaesque novel The Double), Arrival (a linguistic thriller that frustratingly dumbs down a clever premise), and Blade Runner 2049 (a shockingly satisfying sequel to the 1982 cult film) – Villeneuve fills the screen with a vastly uninhabited future where, apart from the occasional shots of faceless, anonymous masses (mostly uniformed soldiers), we only see the few members of the elite classes that engineer and move the story along (there is no Mos Eisley cantina here, or anywhere else where people have an everyday life outside of mindless obedience to the totalitarianism of the regime… and of the plot). This gives the impression that only (political, military, religious) leaders have any meaningful agency in determining the fate of the world and, therefore, only they deserve any interest. For a film about extractive colonialism, it’s quite a colonialist mindset, subordinating everything to the rulers’ perspective.

What’s worse, the rulers themselves appear pretty lifeless, with no quirks or whims outside their role in the overall power plays/plot mechanics, speaking only in portentous statements and sharing a Realpolitik ideology focused exclusively on strength and tradition. I don’t mind the self-seriousness per se (even if I kept speculating about what would’ve been Jodorowsky’s eccentric take on each scene) but, again, the result is a depressingly narrow approach to international politics as based essentially on violent might (at least in Games of Thrones the characters argue and persuade each other through reasoning or manipulation).

Take, as a counterpoint, another movie about monsters tunneling their way through the desert sand, one with a reactionary subtext but with a more humanist execution: Gordon Douglas’ Them!, which is arguably the greatest of the Atomic Era wave of sci-fi/horror films tapping into the double paranoia of radiation-induced mutations and communist infiltration. This 1954 creature feature about nuclear ants compellingly conjures an escalating image of total mobilization against a ruthless, organized enemy, with efficient police forces, scientists, politicians, the military, and ultimately the rest of the population working together (even Joan Weldon’s character, who starts off by being objectified as a woman, soon proves her value and commitment to the fight). Yes, the main opponent is dehumanized, but at least the movie cares enough about people across society to give a personality and dignity to those who aren’t the chosen ones or calling the shots. And it’s not a trade-off: in its own way, Them! is also impeccably shot, grippingly paced, and blessed with a genuinely eerie sound design (it certainly set the standard for later riffs on this sort of material, like the very cool Tremors)… The first half-hour, in particular, is a masterclass of tension, especially if you manage to get someone to watch it who doesn’t yet know what to expect (unfortunately, the poster spoils the surprise).

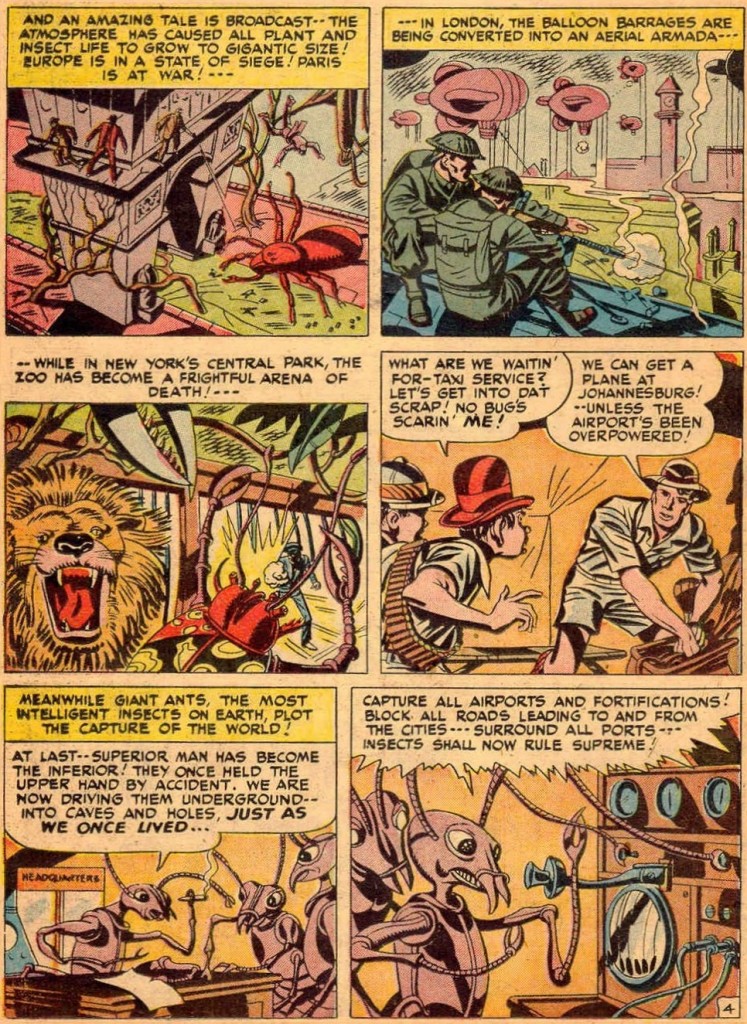

That said – and as a reminder that comics can be awesome – I cannot help but wonder how much of Them! was influenced by Jack Kirby: