Movie blockbusters have been moving into an ouroboros-like postmodern entropy for a while, from Ready Player One and the LEGO franchise to Space Jam: A New Legacy and Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers, not to mention the whole MCU meta-series (whose Spider-Man: No Way Home even retroactively sucked non-MCU films into its canon). By now, the novelty is wearing thin and it’s hard not to see in these IP crossover extravaganzas a cynical, fan-pandering corporate strategy that rewards recognition over innovation.

Still, at its best the multiverse can nevertheless be a fun storytelling device, as proven earlier this year by Everything Everywhere All At Once (whose eclectic intertextuality – from Ang Lee to Wong Kar-wai, from 2001: A Space Odyssey to Ratatouille – is only one of its many gloriously bizarre choices) and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (whose loudest laughs come precisely from the liberating joy of conjuring alternate versions of Marvel characters and then exploiting the freedom to do anything to them).

Besides the obvious brand cross-promotion by mega media conglomerates, I like to think this movement is also a side effect of the growing symbiosis between cinema and comic books (problematic as it is)… and not just because unlikely, overcrowded crossovers have been the latter medium’s bread & butter for ages (taken to a delirious extreme in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen), but also because alternate realities are one of comics’ most beloved tropes.

To be sure, science fiction has been mining alternate realities for ages, including in classics like Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, which uses the what-if-the-Axis-had-won-WWII premise to do a complex, thought-provoking meditation on colonialism and racism in America. Yet I would argue the multiverse has a very specific tradition in comics… At least ever since Gardner Fox wrote the first team-up between the Flashes from Earth-1 and Earth-2, this has become a staple device for fixing – or linking up – continuities.

And not just that: imagining offbeat variations of a familiar world can serve to denaturalize what we take for granted (making the normal strange again) and to highlight what’s special about specific heroes and their contexts. As a result, tons of creators have had a blast with the infinite possibilities of a multiverse, whether in The Many Worlds of Tesla Strong (where at one point the protagonist surfs into a dimension where everything looks pretty much the same except that everybody is nude) or in Ivar, Timewalker (where a background gag suggests a world where Native Americans have a lacrosse team called ‘Whiteys’ whose mascot is a silly-looking pilgrim).

This is not just a subgenre of large superhero universes, either. In fact, today I want to spotlight a trio of nifty comics that did wonders with this concept without the need to tie into existing franchises…

THE INFINITE VACATION

In 2011’s The Infinite Vacation, travel between alternate realities has become a massive commercial enterprise (a market dominated by the titular company), with 97% of people in the western world regularly displacing themselves into parallel universes where their life turned out differently. In this mind-bending scenario, we follow the vacation-obsessed Mark as he tries to figure out why all the other Marks suddenly seem to be dying… while also trying to romance Claire, a girl who rejects the escapism provided by The Infinite Vacation. The comic thus explores the paradox at the heart of the concept of a multiverse made up of the infinite ramifications of every decision and contingency in your life, demonstrating how this notion can be both liberating (tapping into endless possibilities) and limiting (obsessing about alternative paths rather than dealing with the consequences of your own reality).

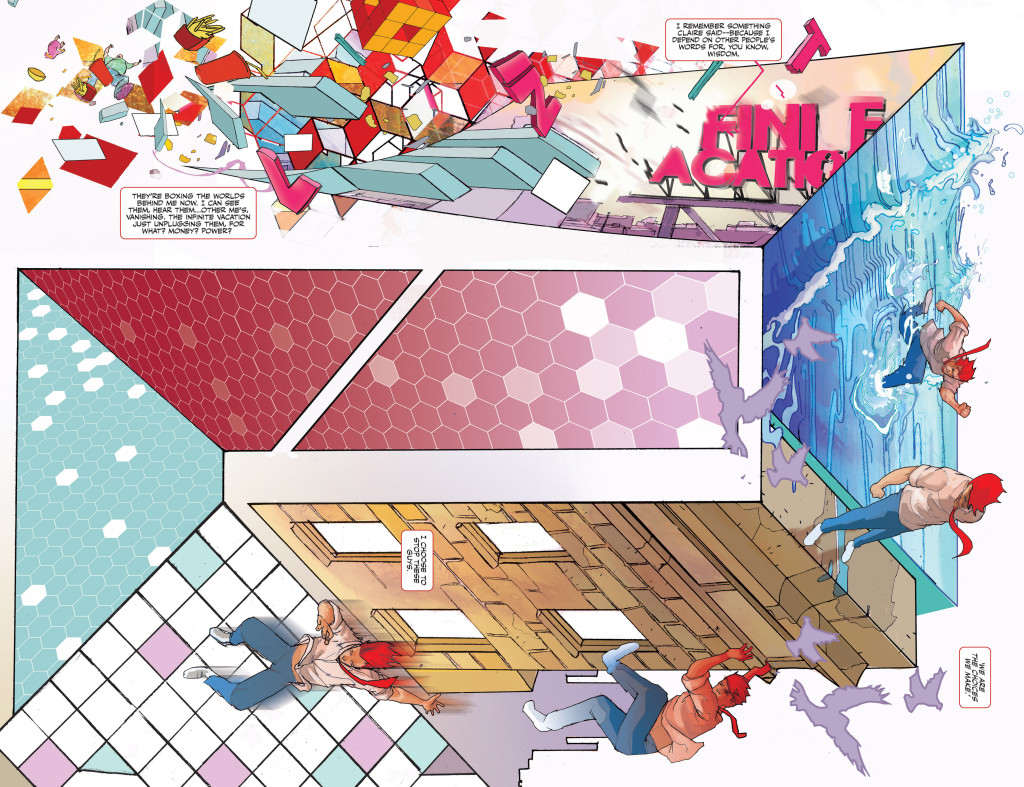

Because the whole thing is written by Nick Spencer, there’s much humor along the way (‘Everyone has themselves for a therapist now. No one knows you like you, right?’). Yet what makes The Infinite Vacation stand out is Christian Ward’s art, which combines highly experimental layouts, weird collages, innovative uses of digital coloring, and even photo-novel techniques, working with the amazing Jeff Powell (the letterer of Atomic Robo). The result is a sci-fi indie love story that, sadly, appears to have gotten buried among all the other genre stuff on the shelves, too idiosyncratic for the adventure crowd (despite featuring plenty of action and violence) yet too conventional for the more demanding critics (in contrast to, say, all the praise showered a few years later onto Daniel Clowes’ Patience, which isn’t nearly as entertaining).

MOTHERLANDS

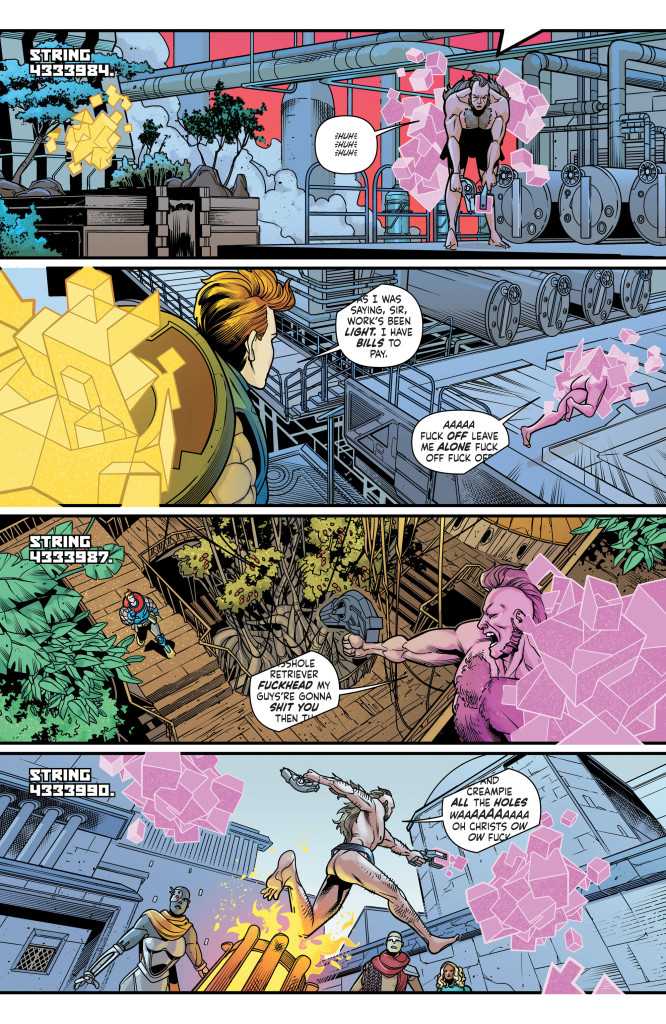

Instead of using the multiverse to explore notions of consequence and escapism, Motherland uses it as an open-ended gateway into bonkers science fiction by positing that contact between billions of parallel earths (called ‘strings’) and the subsequent mashing of their technologies (called ‘The Pollination Revolution’) led to a cyberpunk future where dimension-hopping bounty hunters (‘retrievers’) chase after mad-science bandits. Against this colorful backdrop, reality TV shows covering the retrievers’ exploits used to be a major source of popular entertainment (aka ‘huntertainment’), but those glory days are over and the job has become bloodier and less inventive… This is why Tabitha Tubach, when going after the multiverse’s most wanted research terrorist, has to team up with a former superstar/psychopath whose old implants may give them an edge in the hunt – and who also happens to be her mom!

The genius of Motherlands lies in its ability to satisfy on multiple fronts: not only does it spin a hilariously twist-filled chase yarn drenched in sci-fi strangeness (you haven’t seen anything yet until you’ve seen the interior of a ‘neuroboosted placentamorph’), but it also delivers an oddly compelling – if nasty as hell – family drama about abuse and neglect. Simon Spurrier is one of those writers who is bound to be rediscovered somewhere down the line by people who have no idea of the sort of intelligent, provocative stuff he’s been sneaking into niche projects (such as the film blanc-like Numbercruncher) as well as into more mainstream comics (including a remarkable run on Hellblazer). Among Motherland’s chaos, plentiful sex, and creative profanity, Spurrier somehow manages to make readers truly care about this dysfunctional mother-daughter relationship, culminating in a perfect punchline.

I’m sure it’s not easy for artists to keep up with such a barrage of moods and ideas, but Rachel Stott – inked by Felipe Sobreiro and occasionally backed up by Stephen Byrne and Pete Woods – pulls it off. On the surface, the whole thing may seem like your average action fest, especially if compared with the more aesthetically daring The Infinite Vacation, but some of the designs are quite original (starting with the plus-size Tabitha), the ‘acting’ is expressive enough to sell the drama, and the visuals ingeniously display this world’s madcap technology at work, as shown in the scan above (where you can also see letterer Simon Bowland joining the fun).

CASANOVA

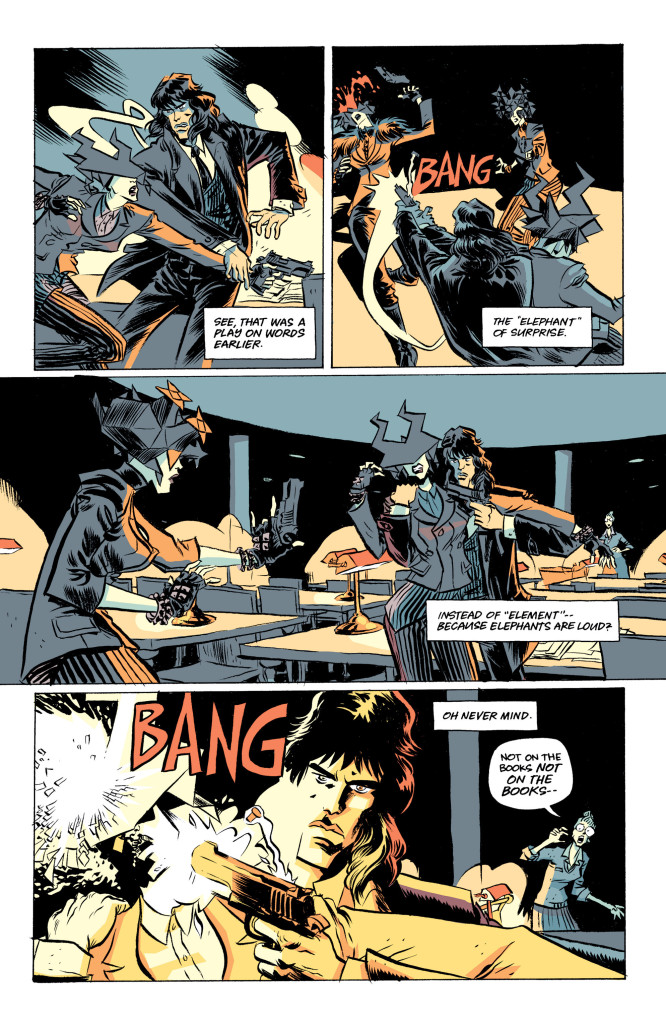

Merge The Infinite Vacation’s whimsical alternative-versions-of-you narrative labyrinth with Motherland’s screwed up family dynamics, ramp up the gonzo science and add some super-espionage and the occasional metafictional gag into the mix… and you get Casanova, a trippy thriller with a frenzied pace and a hip attitude oozing from every line of dialogue. The titular psychic spy is the ultimate double agent – not only does he keep switching sides, he also switches dimensions, as his adventures become increasingly (and wonderfully) convoluted. I’ve recommended this comic before, but I think it’s appropriate to bring it up again as one of the finest examples of how to play with the multiverse, using the parallel timelines as part of an overall leitmotif of fluid, unstable identity, also reflected in the intricate web of secret organizations with mysterious acronyms as well as in the various subplots about automatons with artificial minds (and, more often than not, voluptuous bodies).

Since its debut in 2006, Casanova has taken the form of an irregularly published series of mini-series, with each storyline named after a deadly sin while evoking different music and drugs… Luxuria and Gula were cartoony spy-fi romps, weaving an ongoing saga around specific missions bursting with wild concepts and groovy visuals, from the Recreational Supermechanix Helicasino (‘a black helicopter with delusions of Monte Carlo’) to something called ‘zen crime’ (‘It’s like crime, only there’re no victims, and really, no crimes. It really just spreads a general sense of unrest.’). Spacetime travel took center stage and was pushed to head-scratching limits in Avaritia, which felt like the ambitious culmination of an epic, seemingly bringing closure to various character arcs yet also leaving enough dangling threads to make us thirsty for more. Acedia, then, provided a sort of interlude or detour, as it was mostly set in a Los Angeles where we met alternate versions of several cast members in an occult mystery tale clearly inspired by Thomas Pynchon (who had already been name-dropped in an earlier volume). It ended on an unresolved note, so I can’t wait to see what lies ahead!

You can tell this is a labor of love for everyone involved, from Matt Fraction’s surreal creations and puzzle box-like plotting (which rewards multiple rereads) all the way to Dustin Harvin’s hand-lettered captions, not to mention the alternating artwork by the wonder twins Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon (whose styles are as extravagantly sexy and cheerful as Fraction’s scripts). The original comics had a minimalistic palette (first black & white & green, followed by black & white & blue), but Cris Peter recolored the later editions and has since then become a regular member of the team – and while I still prefer the monotone versions, I admit her unnaturalistic choices are a perfect fit, powerfully bringing out Casanova’s dreamlike mood. Again, as you can see in the excerpt above, it all comes together beautifully.