We are living in sci-fi times – not in the sense that what we are living is fictional, but in the sense that lately reality has been enacting so many tropes of science fiction that it feels like we have seen a version of all this before, on the screen and on the page, making it simultaneously easier and more difficult to accept the current turn of events. If nothing else, the one thing this crisis might do is to make us reconsider our previous engagement with the apocalyptic imaginary, not to mention our engagement with sci-fi as a whole. With that in mind – and because I also like books without pictures – let’s do a bit of time traveling today and look at a couple of very cool classics of sci-fi literature:

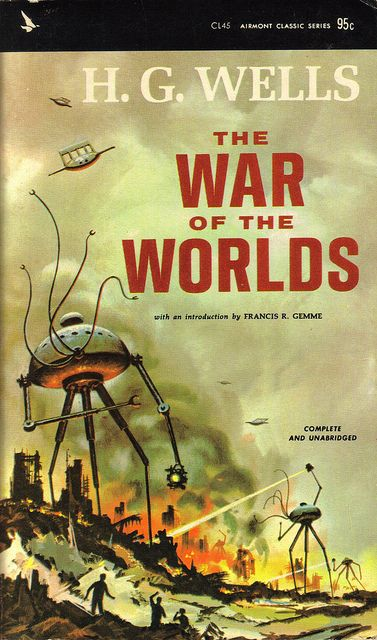

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

(H.G. Wells, 1898)

“No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same. No one gave a thought to the older worlds of space as sources of human danger, or thought of them only to dismiss the idea of life upon them as impossible or improbable. It is curious to recall some of the mental habits of those departed days. At most terrestrial men fancied there might be other men upon Mars, perhaps inferior to themselves and ready to welcome a missionary enterprise. Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. And early in the twentieth century came the great disillusionment.”

The granddaddy of alien invasion stories is quite a fun read. You’ve seen it all since then, but because H.G. Well’s novel is set at the beginning of the twentieth century (a few years after it was written), this tale about a Martian attack against Victorian England now retroactively oozes with a neat steampunk horror vibe. Between the locals’ quaintness and the elites’ smugness, nobody seems to have ever conceived of the possibility of such an attack (not even through previous science fiction, since this was quite a new concept) – convinced of their civilizational superiority yet utterly helpless and unprepared, these humans are the perfect cannon fodder, making the invasion come across as particularly vicious. Hell, if anything, the fact that, after over a century of Wells-inspired popular culture, we (unlike them) can imagine what they’re up against now makes The War of the Worlds a chilling reading experience from the get-go.

That said, while part of the sense of danger stems from the ways in which the spread of information is conditioned by the era’s relatively precarious communication networks, there are also interesting parallels with the current corona-shaped times: the Londoners’ amusing disregard for the events in the countryside brings to mind the West’s attitude earlier this year towards what was initially perceived as a Chinese issue.

It helps that Wells is quite a witty, compelling writer, his prose painting a set of vivid pictures while sadistically escalating the stakes in a nightmarish spiral. To a great degree, this is a war story (as the title suggests) and – before going into full adventure mode later on – the book’s narrator often sounds like a correspondent in the field, witnessing battles, reconstituting events from others’ accounts, editorializing about larger processes at play, and occasionally zooming into human interest pieces. I especially like his first disturbed description of the Martians:

“Those who have never seen a living Martian can scarcely imagine the strange horror of its appearance. The peculiar V-shaped mouth with its pointed upper lip, the absence of brow ridges, the absence of a chin beneath the wedgelike lower lip, the incessant quivering of this mouth, the Gorgon groups of tentacles, the tumultuous breathing of the lungs in a strange atmosphere, the evident heaviness and painfulness of movement due to the greater gravitational energy of the earth—above all, the extraordinary intensity of the immense eyes—were at once vital, intense, inhuman, crippled and monstrous. There was something fungoid in the oily brown skin, something in the clumsy deliberation of the tedious movements unspeakably nasty. Even at this first encounter, this first glimpse, I was overcome with disgust and dread.”

This passage sounds somewhat like a European explorer’s racist accounts of the peoples he has subjected in other continents, but the twist is that the Martians are the conquerors and the British are now the natives about to be slaughtered.

In addition to the overall irony of having Mars (named after the God of War) create a battlefield in the heart of a nation that waged war around the world, many passages seem to mock the era’s militaristic spirit, with characters (including the narrator) at first feeling excited about the notion of a bellic venture, only to be shocked by the devastating impact of large-scale armed conflict.

You don’t have to see in it an allegory about imperialism, specifically. Government, society, religion, and science all seem to collapse in the face of what is ultimately a lesson in humility directed at human hubris, so that you can read The War of the Worlds as an entertaining deconstruction of the Anthropocene, emphasized by the final twist (which comes across as particularly resonant in 2020). Or you can even disregard the subtext and just let yourself be blown away by Wells’ brutal, prophetic depictions of warfare:

“One has to imagine, as well as one may, the fate of those batteries towards Esher, waiting so tensely in the twilight. Survivors there were none. One may picture the orderly expectation, the officers alert and watchful, the gunners ready, the ammunition piled to hand, the limber gunners with their horses and wagons, the groups of civilian spectators standing as near as they were permitted, the evening stillness, the ambulances and hospital tents with the burned and wounded from Weybridge; then the dull resonance of the shots the Martians fired, and the clumsy projectile whirling over the trees and houses and smashing amid the neighbouring fields.

One may picture, too, the sudden shifting of the attention, the swiftly spreading coils and bellyings of that blackness advancing headlong, towering heavenward, turning the twilight to a palpable darkness, a strange and horrible antagonist of vapour striding upon its victims, men and horses near it seen dimly, running, shrieking, falling headlong, shouts of dismay, the guns suddenly abandoned, men choking and writhing on the ground, and the swift broadening-out of the opaque cone of smoke. And then night and extinction—nothing but a silent mass of impenetrable vapour hiding its dead.”

THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS

(Ursula K. Le Guin, 1969)

“I’ll make my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child on my homeworld that Truth is a matter of the imagination. The soundest fact may fail or prevail in the style of its telling: like that singular organic jewel of our seas, which grows brighter as one woman wears it and, worn by another, dulls and goes to dust. Facts are no more solid, coherent, round, and real than pearls are. But both are sensitive.”

Ursula K. Le Guin’s acclaimed novel about Genly Ai, an envoy trying to convince the civilizations of the ultra-cold planet Gethen (also known as Winter) to join the Ekumen intergalactic alliance, remains an absolutely stunning masterpiece. While the voice shifts from chapter to chapter (including scientific reports, diplomatic transcripts, and mythological tales passed on by oral tradition), the bulk of the book follows Ai’s narration, his observations about Gethen’s bewildering politics, religion, biology, and overall social dynamics serving as a vehicle for Le Guin to muse on topics such as war, language, patriotism, and sex.

Like The War of the Worlds and, indeed, like all the best sci-fi fantasy – once you go deep into alien species and cultures, the border between the two genres becomes fuzzy – by conjuring up a whole other world, The Left Hand of Darkness denaturalizes ours. It imaginatively and provocatively exposes how limited many of our preconceptions are, whether regarding time (‘It is always the Year One here. Only the dating of every past and future year changes each New Year’s Day, as one counts backwards or forwards from the unitary Now.’), regarding spirituality (‘The Handdara is a religion without institution, without priests, without hierarchy, without vows, without creed; I am still unable to say whether it has a God or not.’), or, above all, regarding gender roles (‘The king was pregnant.’).

Gethen’s inhabitants are a specific type of hermaphrodites, which means they’ve developed highly distinct approaches to family values and reproduction (one of the most striking chapters is a treaty on alien sexuality). A running motif in the book is how Genly Ai, who has managed to mostly cope with the planet’s wild climate and possibly supernatural premonitory cults, feels constantly challenged by this one feature above all others…

“Though I had been nearly two years on Winter I was still far from being able to see the people of the planet through their own eyes. I tried to, but my efforts took the form of self-consciously seeing a Gethenian first as a man, then as a woman, forcing him into those categories so irrelevant to his nature and so essential to my own. Thus as I sipped my smoking sour beer I thought that at table Estraven’s performance had been womanly, all charm and tact and lack of substance, specious and adroit. Was it in fact perhaps this soft supple femininity that I disliked and distrusted in him? For it was impossible to think of him as a woman, that dark, ironic, powerful presence near me in the firelit darkness, and yet whenever I thought of him as a man I felt a sense of falseness, of imposture: in him, or in my own attitude towards him?”

As you can tell, the whole thing is extremely well-written. Ursula Le Guin conveys thoughtful, subtly playful insights under the guise of an anthropological gaze that reminds me of Jorge Luis Borges’ style in short stories like ‘Brodie’s Report’ and ‘The Theologians.’ Yet because the characters are so fully realized and because some chapters are narrated by native Gethenians, we are prompted not just to respond to their strangeness, but also to engage with their perspective from within, which makes The Left Hand of Darkness an especially rich reading experience. The beauty of it lies precisely in the mix of dry tone and surreal elements, i.e. of science and fiction. And while the amount of foreign names and terminology can be a bit daunting at first, at the heart of the novel is a truly engrossing political thriller.

The Left Hand of Darkness is arguably the most well-known of Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle, a series of loosely connected books related to the Ekumen league of planets. It is mainly remembered for its final third, which many see as a powerful kind of love story and/or a seminal – if dated, in some respects – feminist text touching on issues of queerness and transphobia. Readers of this blog, however, may be interested to know that, on top of those things, it is also one hell of an action adventure yarn, with breathtaking descriptions of the protagonists’ perilous journey through the harshest of landscapes and weather conditions…

“We seldom talked while on the march or at lunch, for our lips were sore, and when one’s own mouth was open the cold got inside, hurting teeth and throat and lungs; it was necessary to keep the mouth closed and breathe through the nose, at least when the air was forty or fifty degrees below freezing. When it went on lower than that, the whole breathing process was further complicated by the rapid freezing of one’s exhaled breath; if you didn’t look out your nostrils might freeze shut, and then to keep from suffocating you would gasp in a lungful of razors.

Under certain conditions our exhalations freezing instantly made a tiny cracking noise, like distant firecrackers, and a shower of crystals: each breath a snowstorm.”