Man-Bat isn’t one of the most inspired concepts in Batman comics. Taking to the extreme the notion that great villains are an inversion of the heroes, Man-Bat’s name is a literal reversal of Batman’s… As for his origin, it’s just another retread of the old Jekyll and Hyde formula, as zoologist Kirk Langstrom takes a bat-gland extract and ends up becoming a bat-like mutant.

Still, I have a certain fascination for the pre-Crisis version of Man-Bat. He’s neither your regular Batman foe nor your regular Batman ally… He is basically a deranged asshole who hangs around Gotham City and unintentionally makes everyone’s life miserable, thus ushering in a strand of stories that aren’t your regular Batman adventures.

Detective Comics #400

Detective Comics #400

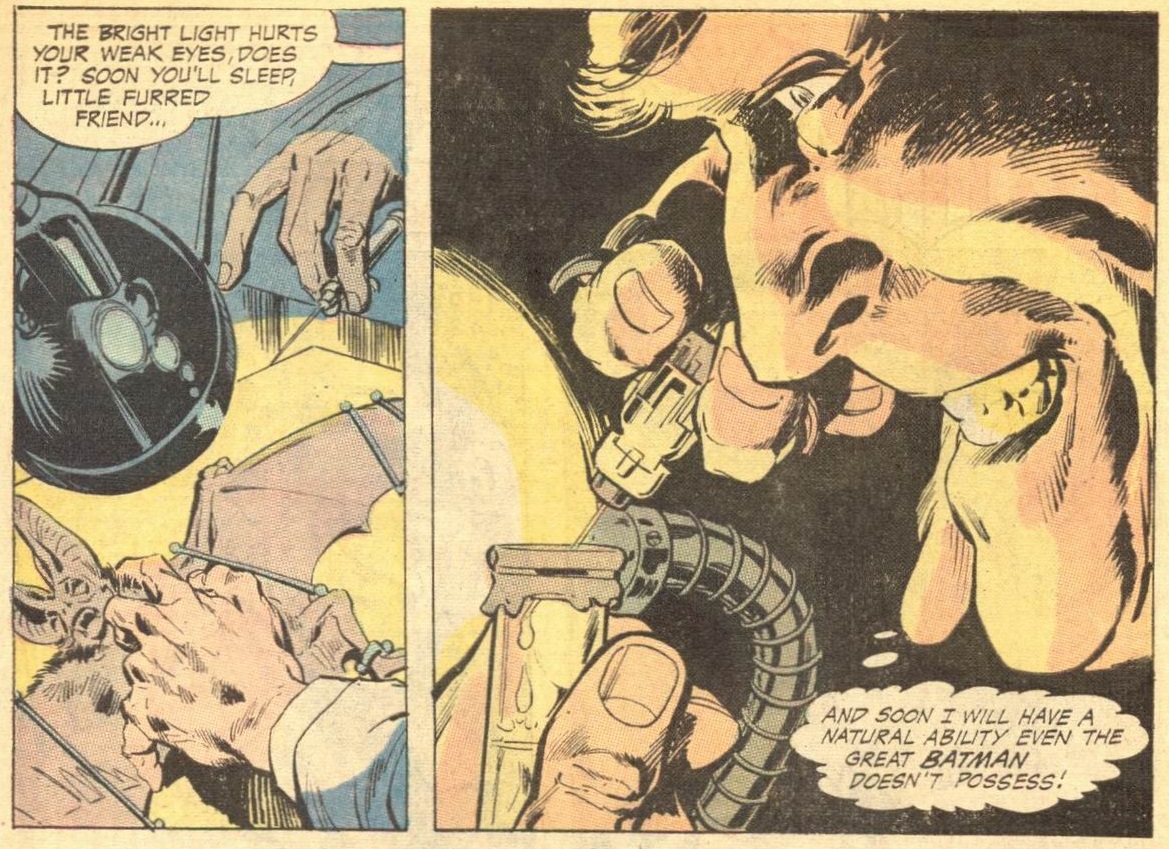

To be sure, as simple and stupid as the concept of Man-Bat may sound, his debut in Detective Comics #400 (cover-dated June 1970) was actually quite neat… Yes, a lot of the story’s success derives from the excellent decision to have Neal Adams illustrate it (with inks by Dick Giordano). With the possible exception of Bernie Wrightson, no one could have come up with such a great monstrous design and infused the art with the required gothic atmosphere to sell this idea. Adams gave the material a classy treatment from the very first page, introducing a Kirk Langstrom who resembled Peter Cushing’s mad scientist in Hammer’s Frankenstein film series (which, in the previous year, had released its most macabre installment, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed).

To Frank Robbins’ credit, he doesn’t just write a horror story about a man physically transforming into a monster, nor is he satisfied with the parallel between a man who inadvertently looks like a bat and a man who deliberately chose to look like one, even if that is obviously there as well:

Detective Comics #400

Detective Comics #400

That first story involves the Blackout Gang – a gang of thieves who operate in the dark and in total silence with the help of “light intensifier” goggles, foam-soled shoes, and ultra-sonic cutting tools. Sure, they’re a convenient plot device to give Man-Bat a chance to show off his sonar, but they also help unfold a kaleidoscopic mirror house effect. Everyone in the story seems to be trying to emulate bats. Add to this the collection of giant papier-mâché bats at the Gotham Museum of Natural History where we first meet Langstrom (and where he later hides) and you have a comic in which the man/bat motif resonates in every single page.

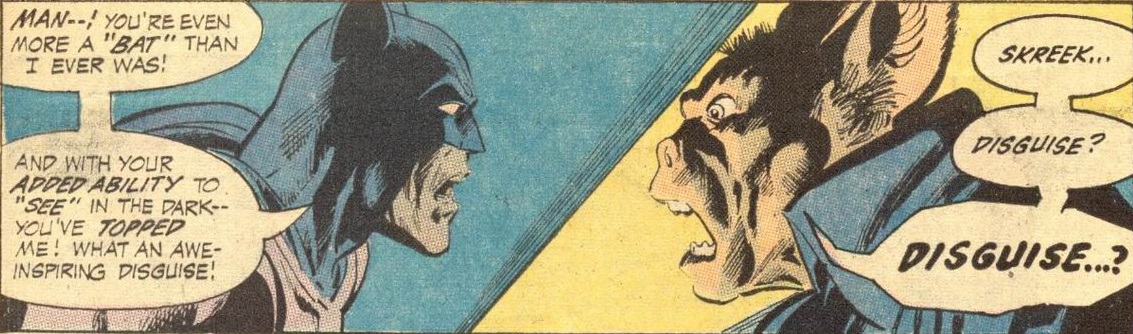

Following up on this introduction, Detective Comics #402 and #407 round up the character’s initial storyline. This trilogy establishes practically all of the main elements of the Man-Bat mythos. The second part pits Batman and Man-Bat against each other as Langstrom completes his transition into a winged creature, losing his humanity psychologically as well as physically. The third part expands the role of Kirk’s fiancée, Francine Lee, who sacrifices her own humanity to be with her mutated lover, giving the saga even more of a gothic tragedy flavor.

This issue also provides one of the best replies to the age-old wedding tradition of asking guests if anyone sees fit why the marriage should not be consummated:

Detective Comics #407

Detective Comics #407

On the one hand, Batman’s role may come across as particularly reactionary – since Kirk Langstrom consciously refuses to stop being Man-Bat and Francine’s sacrifice is put in terms of her losing her ‘human beauty,’ the Caped Crusader’s main problem seems to be merely that the couple look like inhuman beasts. Francine would thus appear to be much nobler, as she is willing to accept Kirk in spite of his deformity.

On the other hand, even if haphazardly, the story does suggest that the cost of turning into Man-Bat is not just ugliness, but insane rampage as well. This crucial point is better developed in later instalments, starting with the Langstroms’ next appearance, in the suitably titled ‘Man-Bat Madness,’ now under Frank Robbins’ own stylized pencils.

Detective Comics #416

Detective Comics #416

The link between loss of conventional beauty and murderous rage is a classic Batman motif, also seen in villains such as Two-Face and Clayface. Robbins himself used this motif to great effect in ‘Man in the Eternal Mask’ (Detective Comics #409), about a disfigured killer out for revenge not only against the one he blames for his mutilation but against the art that immortalized his previous looks and that now torments him as a reminder of his loss (the tale finishes with a twist on The Portrait of Dorian Day, as the killer attacks his beautiful portrait and is ultimately defeated by it).

But, again, Man-Bat is a different sort of beast. Kirk Langstrom’s madness does not derive from his revolt at having been turned into a monster – after all, no matter how unintentional it was, the transformation was completely self-inflicted, so there is no one to blame but himself. For the most part, Kirk just comes across like a jerk.

It doesn’t help that he is the worst husband ever. As if it wasn’t bad enough that he keeps turning into a monster and is responsible for his wife turning into one as well, in ‘Man-Bat over Vegas’ he is even willing to shoot Francine just to solve the latest Man-Bat outburst:

Detective Comics #429

Detective Comics #429

Frank Robbins’ final Man-Bat story was ‘King of the Gotham Jungle!’ (Batman #254), which threw the character in a different direction. Rather than a curse that turns him mad, Kirk Langstrom’s latest transformation is treated as a deliberate attempt to become a crime-fighter, with Kirk remaining perfectly lucid in his Man-Bat form and the Dark Knight accepting him as a crime-fighting ally.

This status quo leads to ‘Bring Back Killer Krag’ (The Brave and the Bold #119), in which Kirk competes with Batman to capture a mob hitman hidden in a Caribbean fortress (ruled by a dictator who calls himself ‘the Black Napoleon’). Like many of the best issues of The Brave and the Bold written by Bob Haney, this one is packed with fun, wild ideas – the duo faces everything from armed guards to an angry shark, vampire bats, and voodoo executions, building up to an awesome climax in which the Dark Knight himself takes the bat-gland serum!

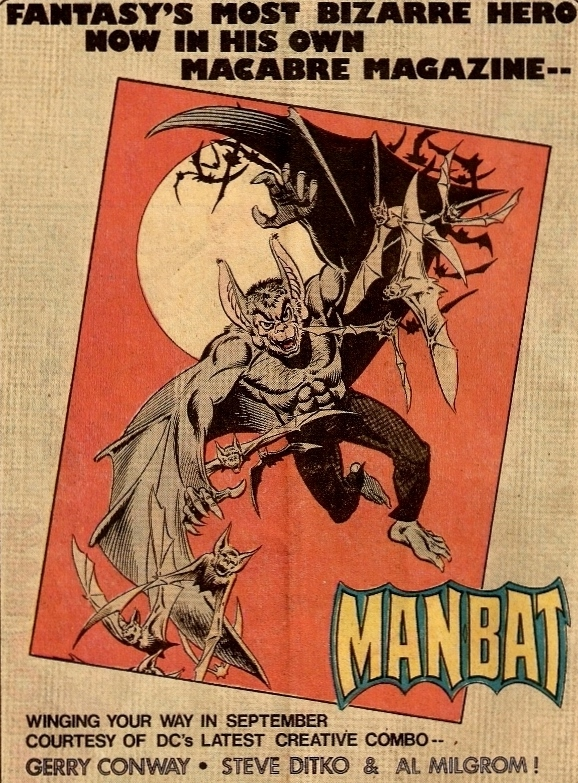

That was followed by a short-lived attempt at a solo series…

…but clearly the world wasn’t ready. The series lasted for two issues before being wrapped up as a backup feature in Detective Comics.

The Langstroms then moved to New York City. Always the horrible husband, Kirk still tried to pursue his Man-Bat crime-fighting career, living precariously on voluntary rewards by grateful citizens, even though his wife was expecting a child. In his defense, Man-Bat did develop a superpower that was as absurd as it was convenient, namely the ability to pick up on the ‘mental radiation’ of criminals (supposedly triggered by their desire and determination to commit a crime). Oh, and he totally fought a guy called SNAFU!

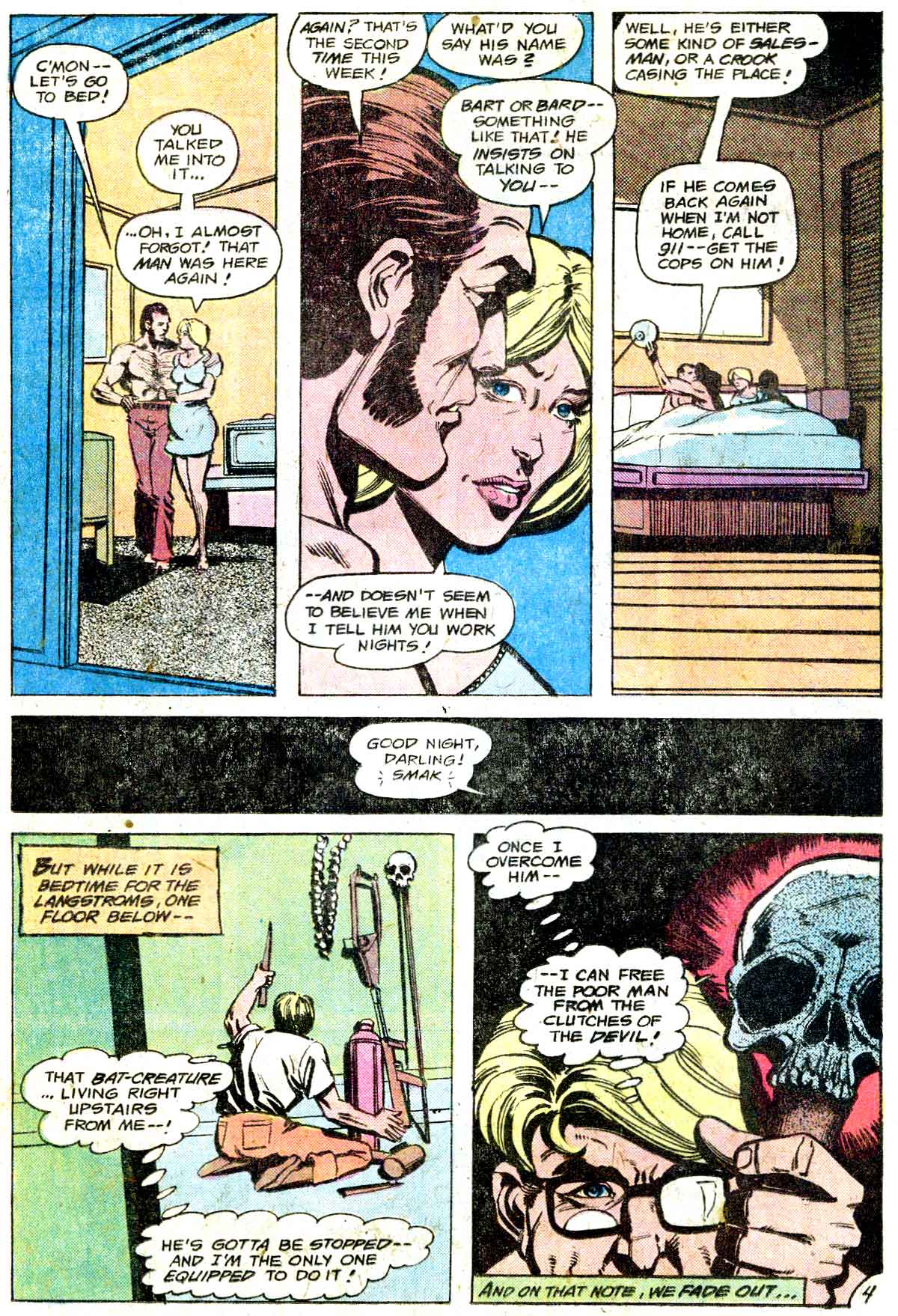

As if it wasn’t enough that Kirk treated his wife so poorly, he also drove his downstairs neighbor insane. Literally:

Batman Family #14

Batman Family #14

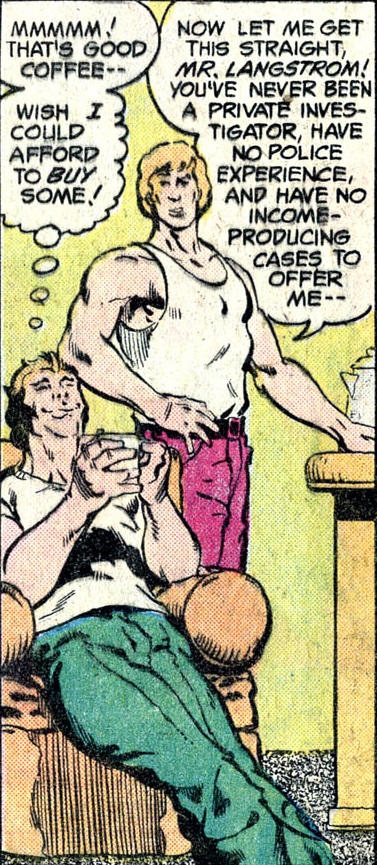

Soon, the deadbeat Kirk Langstrom partnered up with private detective Jason Bard, although not without some convincing:

Batman Family #20

Batman Family #20

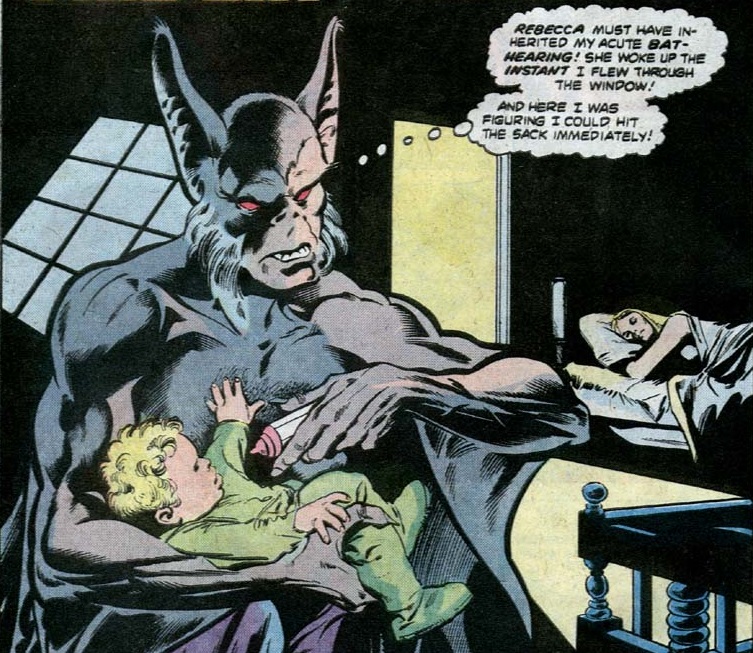

Meanwhile Kirk’s poor daughter, Rebecca Elizabeth Langstrom, is suspected of being a latent demon child (Batman Family #17). Even after that mess is cleared, she turns out to be quite the unhealthy baby, having inherited oversensitive hearing from her parents, which doesn’t let her sleep. And as a father, Kirk brings all the understanding you’d expect from him…

Detective Comics #485

Detective Comics #485

Always one for common sense solutions, Kirk steals a bunch of illegal drugs (banned by the FDA due to dangerous side effects) and hires the dodgiest ‘no-questions-asked’ doctor he can find to fix his daughter’s condition (The Brave and the Bold #165). When Batman wisely prevents him from administering the drugs (which on top of everything else have been contaminated with highly toxic bacteria) to the child, Kirk turns his anger against the Caped Crusader, even after Rebecca gets cured with the help of Superman (DC Comics Presents #35).

Indeed, by the time we get to the early 1980s, Kirk is even more of a mess. Having screwed up the proportions in his own bat-gland formula, he actually forgets his daughter is cured and so he attacks Batman in a completely misguided act of revenge for her supposed death, although not without first engaging in some old-school domestic violence:

Batman #342

Batman #342

Batman finally fixes everything. The Caped Crusader houses Francine when she has a breakdown and confronts Kirk with his live daughter, so that he is shaken out of the Man-Bat state.

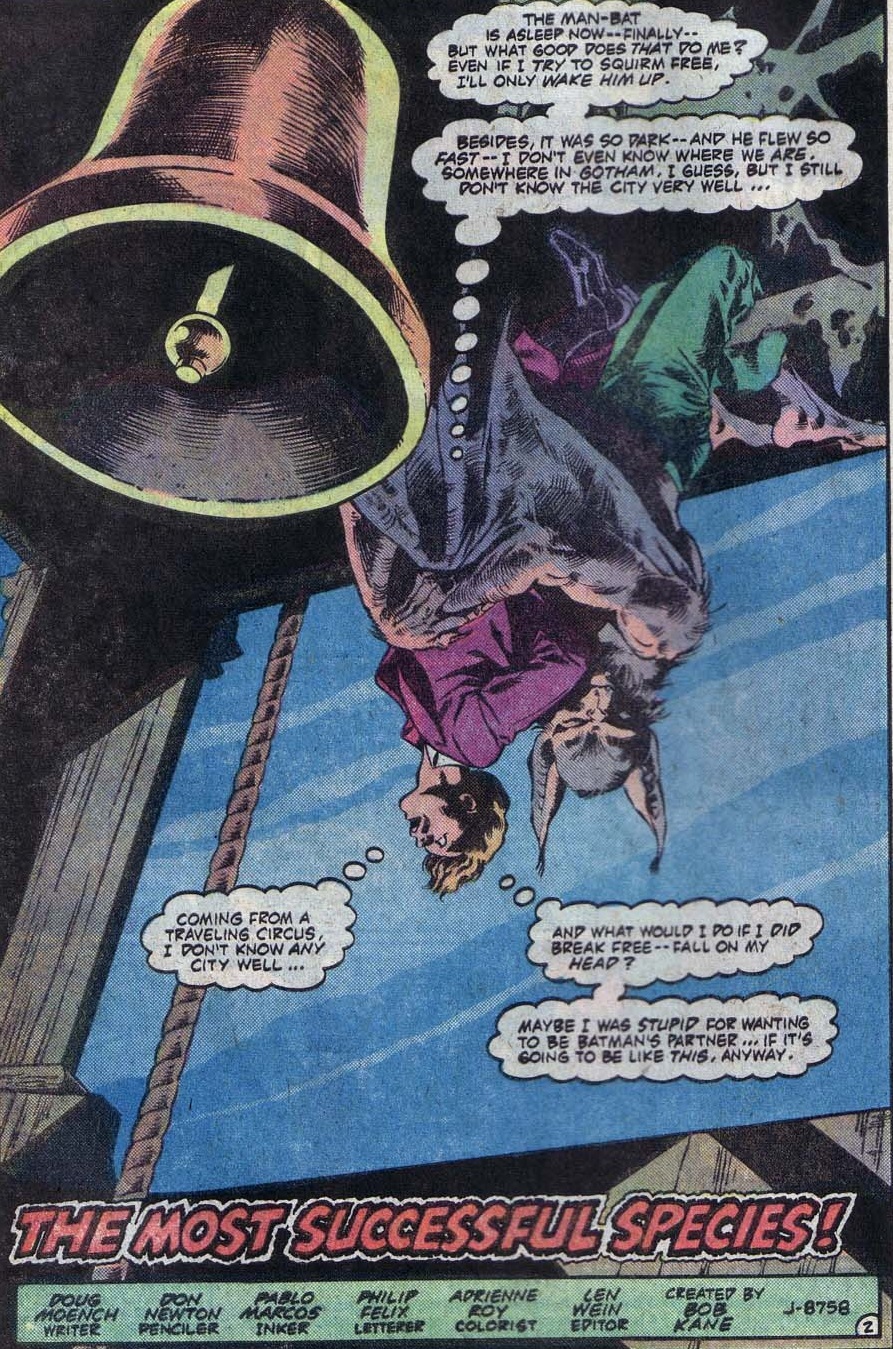

Not long after that, though, the idiot forgets to take his medication and goes on *yet another* vengeance quest for his not-dead daughter, this time kidnapping the closest thing to Batman’s son he can find: Jason Todd, the second Robin. Kirk tries to turn the poor boy into a bat, which leads to this creepy splash page:

Batman #361

Batman #361

The latter is not a bad comic – the art is highly atmospheric and Doug Moench, always one for symbolism overdose, works in a bunch of factoids about bats. He also uses Kirk Langstrom’s family fixation to contrast and develop Bruce’s own fatherly relationship with Jason. However, it is ultimately the same story we’ve seen before over and over again, with Kirk going berserk and Batman injecting him with some antidote in the end.

In theory, this was the last pre-Crisis confrontation between the two. If I’m not mistaken, it would take about a decade for Man-Bat and Batman to meet again in the comics (outside of the Batman Adventures line, that is). However, when Moench revisited the character in 1996 (in Batman #536-538), even though that three-parter was technically set in post-Crisis continuity, the Langstroms’ depiction sure felt like a throwback…

This time around, Kirk gets feral fever because a weird phenomenon has been stretching the night time. Well, the fact that he gets hopped up on hard drugs probably doesn’t help… Anyway, Kirk beats up Francine (again), goes on a rampage in the Gotham night (devouring an alley cat in the process), and then flies off to the North Pole. In the Arctic, Kirk runs into a secret government operation to develop an electromagnetic death-ray, in a typically paranoia-infused Moench twist. It’s a pretty terrible story all around, but of course the main attraction is seeing Man-Bat drawn by the übergothic Kelley Jones:

Batman #536

Batman #536

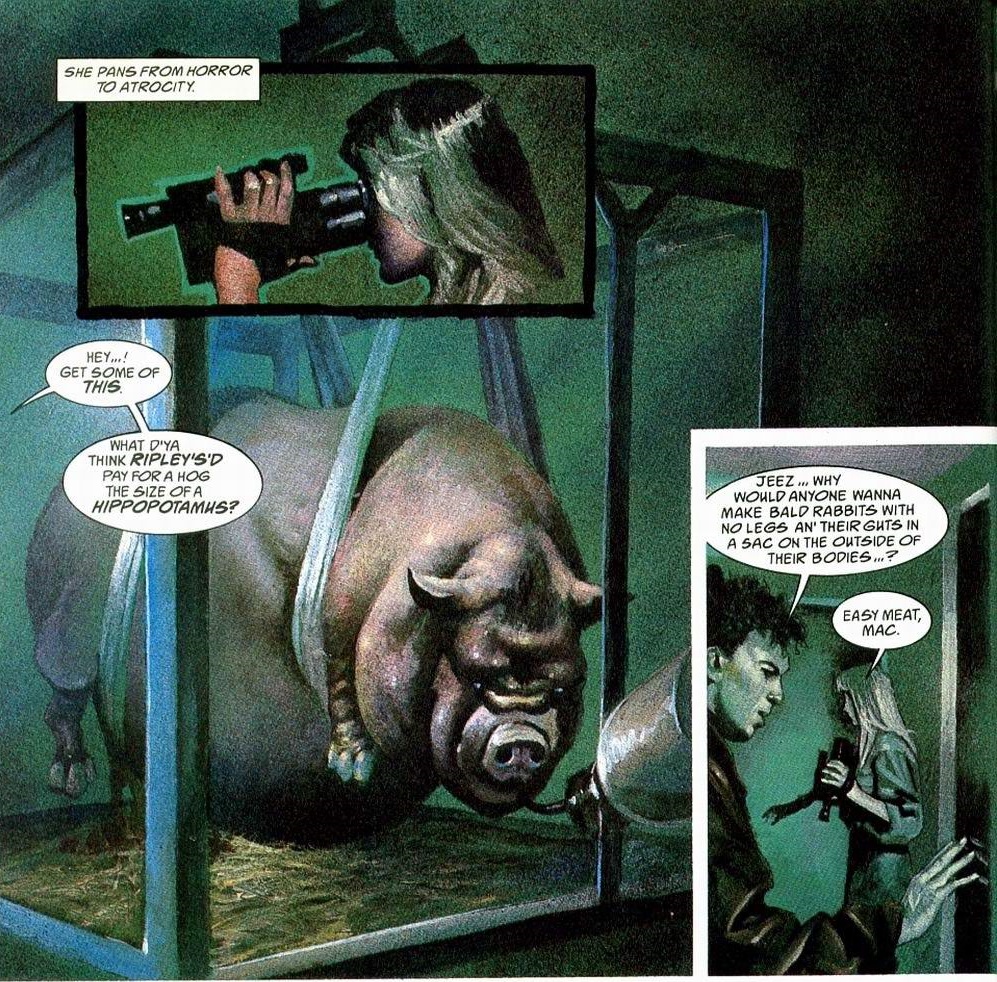

Speaking of writers shoehorning their agenda into Man-Bat comics that are illustrated by eccentric artists: around this time, DC also published Jamie Delano’s and John Bolton’s Manbat, a mini-series about an eco-activist called Marilyn Munro (seriously) who stumbles upon Kirk and Francine Langstrom, now exiled in the desert. Increasingly frustrated with humanity’s environmental crimes and always one for poorly thought out solutions, Kirk has decided to engineer a new species to replace humans.

Delano brought to Manbat the same kind of poetic prose and in-yer-face politics that he had perfected in his runs on Hellblazer and Animal Man, taking advantage of Bolton’s flair for the grotesque in this indictment of vivisection:

Manbat

Manbat

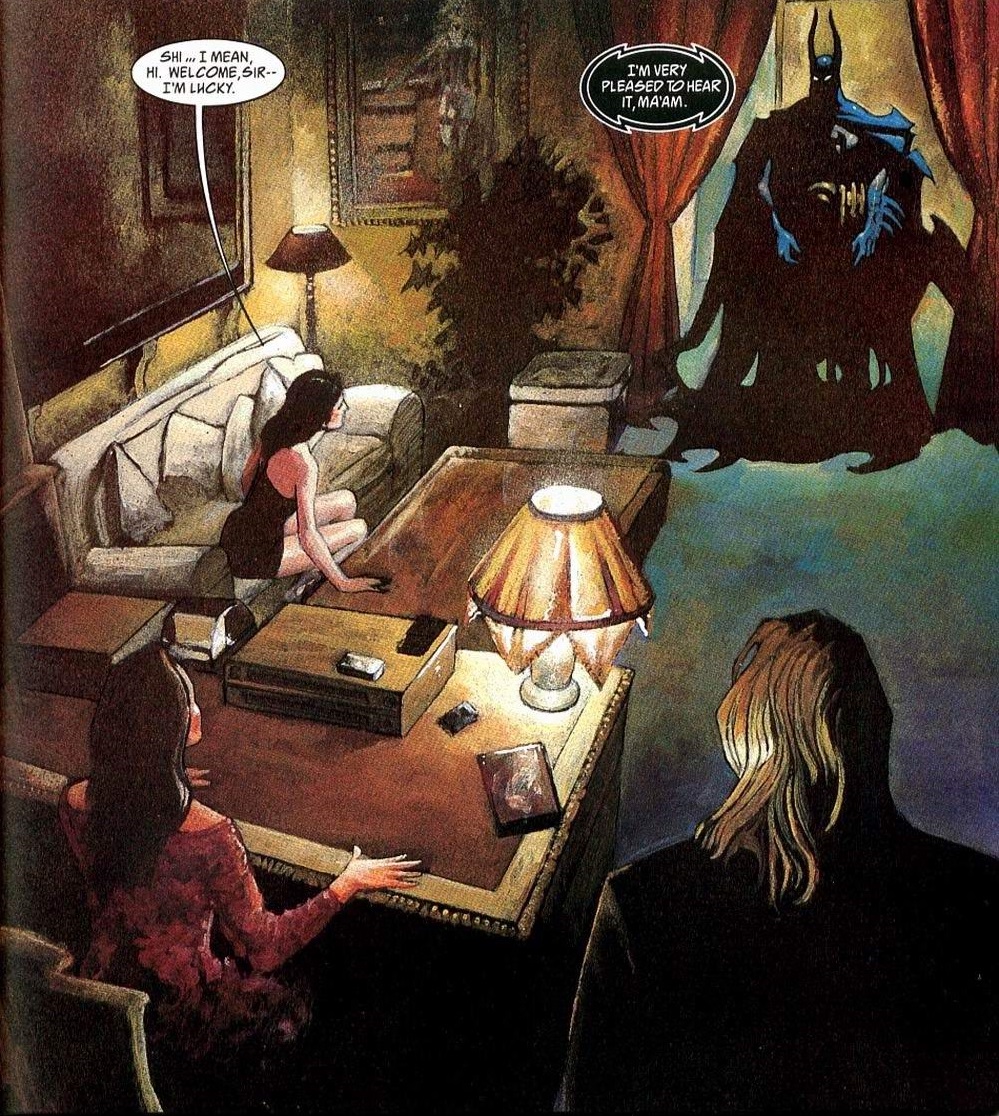

DC labeled Manbat an Elseworlds tale, but it reads more like a sequel to the old stories, showing a logical evolution of the Langstroms (as long as you ignore the fact that they once had a daughter called Rebecca). What really makes this comic worthy of an out-of-continuity sticker is the fact that, even for modern Batman standards, the Dark Knight comes across like a hilariously authoritarian douchebag:

Manbat

Manbat

In fact, the defining reboot of Man-Bat in the post-Crisis continuity was wisely assigned to writer Chuck Dixon, an expert in streamlining and updating old concepts. In Legends of the Dark Knight Annual #5, Dixon efficiently remade the first couple of Man-Bat stories, making Kirk much more likeable in the process. Instead of a mad scientist, Kirk was now more of a tragic figure from the start – a deaf workaholic experimenting with bat genetics in order improve people’s hearing. He was still somewhat of a jerk to Francine (who was now given a scientific background herself), but that became a less prominent feature.

It’s this new Man-Bat that you find in ensuing comics (except for that Moench three-parter). Dixon reintroduced him as a regular supporting character, first in an issue of the anthology Showcase ’94 and then in a 1996 Man-Bat mini-series. They were both illustrated by Flint Henry, who, true to form, drew Man-Bat as the most disgusting creature you can imagine…

Kirk Langstrom has continued to be reinvented and he is still somewhat of a wild card in Batman’s corner of the DCU (albeit not always an interesting one). In those pre-Crisis years, though, when Gotham wasn’t populated with all that many recognizable characters beyond Commissioner Gordon, the Batman family, and the rogues’ gallery, I find it fascinating to follow the parallel adventures of this deluded loser who just keeps screwing up.