Ed Brubaker is one of the most critically acclaimed comic book writers of the 21st century. Heavily influenced by crime fiction and by the superhero revisionist turn of the 1980s, he has continually sought to imbue American comics with a greater degree of realism, psychological depth, decompressed pace, and adult content like sex and drugs (played not for outrageous shock value, but with a generally tasteful sensibility that treats them as important elements in many people’s lives). You can see a quest for maturity and respectability all over his fan-favorite runs on Daredevil and Captain America, not to mention in his collaborations with Sean Phillips for Icon and Image Comics (most notably the neo-noir series Criminal), whose backmatter often includes additional articles on cinema and literature. While other popular creators from the last couple of decades – like Brian K. Vaughan and Rick Remender – tend to target smart, iconoclastic teens, Brubaker seems to be going for a slightly more pretentious crowd for whom comics should be taken as seriously as the kind of films and novels discussed on the back of his books.

I love much of Ed Brubaker’s work, especially the period pieces The Fade Out and Pulp, along with the spy series Velvet and Sleeper. However, while I certainly share several of his references (from film noir and mystery yarns to heist thrillers and espionage), I don’t think his style always does justice to the material at hand. This definitely applies to his uneven stint on Batman comics in the early 2000s.

Detective Comics #784

Detective Comics #784

Having proven his potential with a handful of indie crime comics and Vertigo projects, in 2000 Ed Brubaker, then in his early thirties, was brought in to write Batman, starting with issue #582 and sticking around – with a brief interlude – until #607 (he then carried on for another couple of years, until 2004, writing various other books for the Batman line). I know I’m going against the grain on this one, but I think this initial run displays many of Brubaker’s most frustrating tics as a writer without the redeeming features of his later works.

He started off on the wrong foot with the very first arc (‘Fearless’), which revolves around a new character who is supposed to be both a very close friend of Bruce Wayne (even though we never heard of him) and a brilliant criminal mastermind (with an ultra-clichéd and superficial origin). We learn all this from the explicit narration, but neither of those things is convincingly conveyed within the story, so that when we eventually learn this guy has figured out Batman’s secret ID and when we see Bruce willing to go over the edge for him, it doesn’t feel earned at all… It’s not as if you can’t compellingly establish high emotional stakes about new characters in a brief tale (see, for example, The Batman Adventures #27) or even quickly create a memorable, larger-than-life villain (see Gotham Adventures #49 or the debut of most of Batman’s classic rogues, really), but as far as I’m concerned these issues fail to sell the drama among all the rush. And as if that weren’t enough, they also introduced the super-assassin Philo Zeiss, who turned out to be one of the most uninteresting rogues to ever cross the Dark Knight’s path!

It doesn’t help that the whole run was illustrated by Scott McDaniel, whose dynamic, cartoony pencils hardly match Ed Brubaker’s introspective, relatively down-to-earth tone. Such awkward marriages can occasionally produce something special, but in this case the mismatch simultaneously undermined Brubaker’s literary quality and restrained McDaniel’s visual virtuosity…

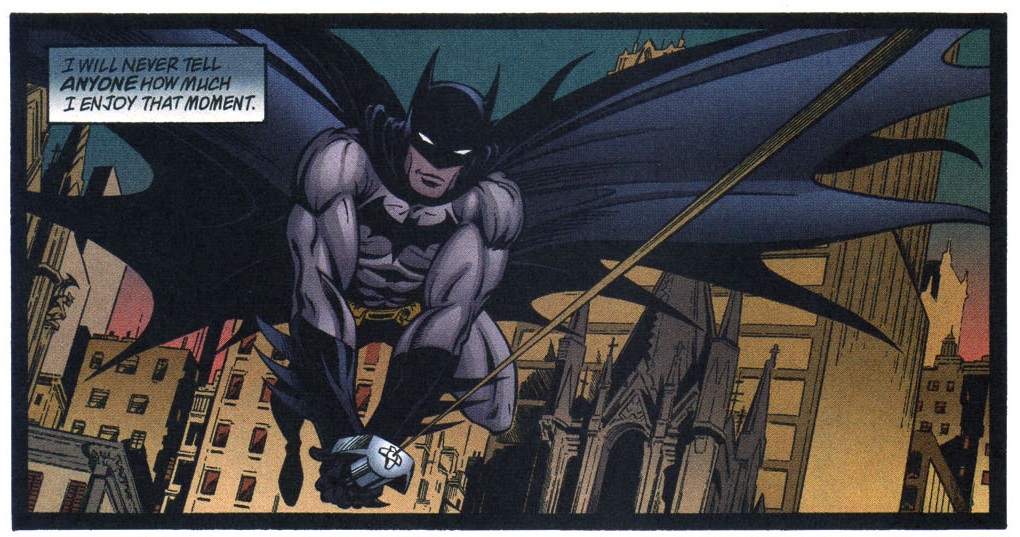

Batman #601

Batman #601

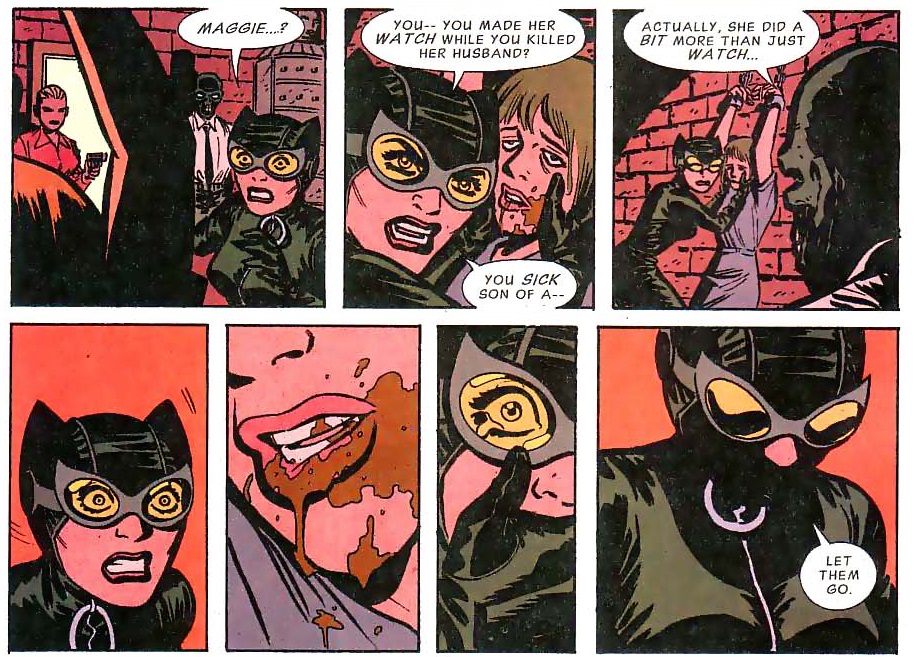

(Brubaker’s final issues on Catwoman suffered from a similar problem, with Paul Gulacy’s sleazy, highly sexualized drawings annihilating any sense of subtlety or sophistication from the script…)

When I see panels like the one above, I’m struck by the lack of fun and imagination, getting very little in return. Perhaps you could get away with something this witless if it was specifically designed to highlight Batman’s desperation and sense of urgency, but this excerpt is not a from a deeply personal mission… The scene isn’t in contrast to the Dark Knight’s usual attitude or to the series’ standard storytelling approach – rather, it is representative of a peculiar era, immediately after Denny O’Neil retired as editor, when Batman comics mostly did away with playfulness and instead pushed bleakness as far as it could go.

And yet, these were still mainstream DC products, so you had this constant sense of dissonance… For instance, on the one hand, the stories were full of rape and prostitution; on the other hand, the swear words continued to be %#&@ing censored.

I wonder if Ed Brubaker himself eventually had the same realization, at some point.

Catwoman (v3) #5

Catwoman (v3) #5

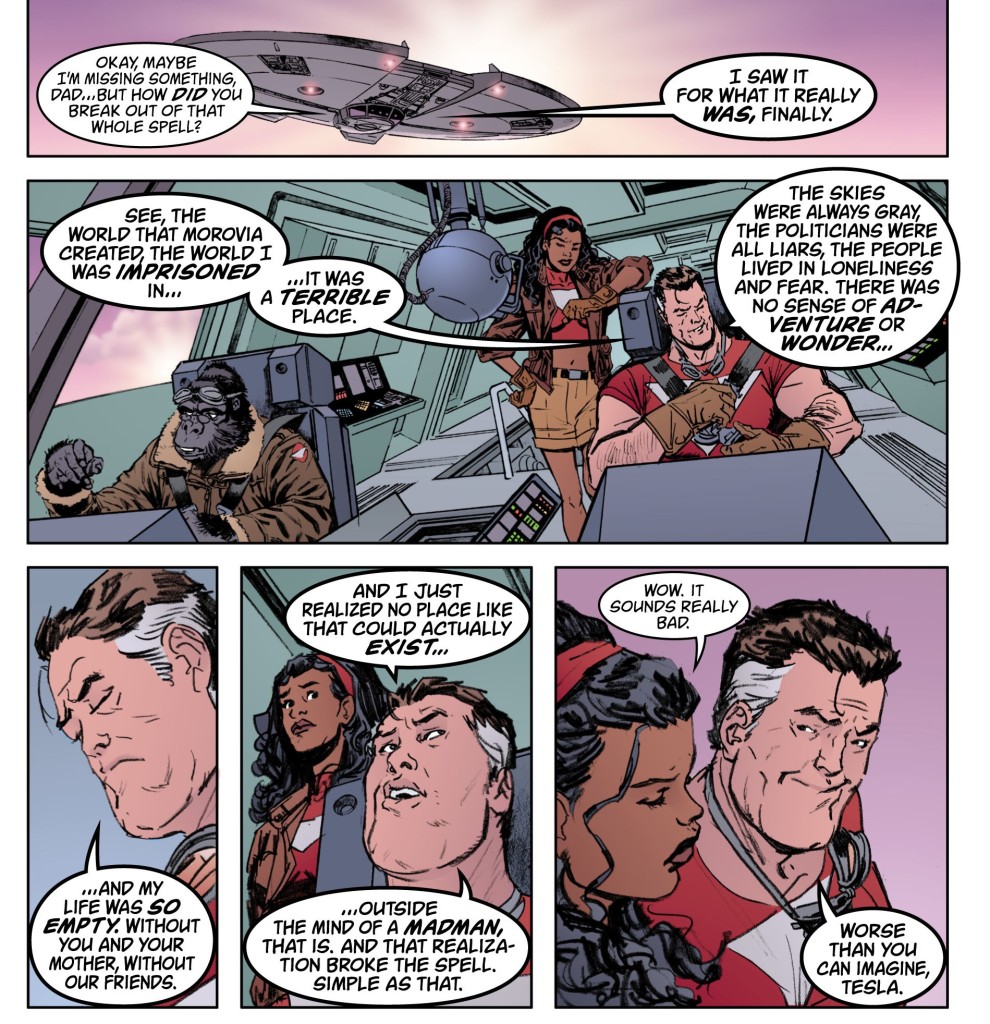

Looking at his 2004 two-parter ‘The Terrible True Life of Tom Strong’ (Tom Strong #29-30), it reads like a meta-epilogue – if not necessarily an outright mea culpa – of Brubaker’s downbeat work on Batman.

In a variation of a familiar story (whose formula harkens at least as far back as Batman’s own ‘Mask’), the square-jawed hero Tom Strong wakes up in a world where it turns out he is actually a delusional loser who has been fantasizing about his alter ego all along. His new reality, then, is akin to ‘our’ reality, i.e. one where costumed crimefighters are pathetic rather than heroic (and where the laws of physics and complex sociopolitics render their exploits impractical and ultimately unethical), or, better yet, akin to the reality simulated in grim-and-gritty revisionist superhero narratives. Brubaker’s script presents such revisionism as not only unpleasant and evil (it’s part of a villain’s masterplan), but also as at odds with the very essence of this type of stories… to the point where Tom Strong is able to see through the hallucination by realizing he just doesn’t fit in such a damned harsh world:

Tom Strong #30

Tom Strong #30

Whether the ‘mind of a madman’ comment above referred to Tom Strong’s creator, Alan Moore (whose quintessential revisionist text, Marvelman, is also riffed on in this comic), or whether it was meant as a self-referential allusion, it perfectly encapsulated the attitude presiding over Ed Brubaker’s then-recent Batman work.

In his defense, that attitude matched the zeitgeist, both in the actual United States of the W. Bush era (especially the post-9/11 obsession with terrorism, torture, and surveillance) and across the DC Universe. After all, there was a kind of audition in 2000, with Ed Brubaker and Brian K. Vaughan penning brief Batman arcs and the editors then picking the former over the latter for the role of regular writer. Vaughan (who also went on to do a pretty nifty Tom Strong fill-in issue, by the way) delivered ‘Close Before Striking,’ ‘Mimsy Were The Borogoves,’ and the short story ‘Skullduggery,’ all of them very cool tales that openly embraced the quirkiness of the Caped Crusader’s world (they’ve been collected in the book False Faces). Yet DC was clearly looking for something less whimsical at the time… They chose Brubaker, who, besides showing little interest in colorful rogues with offbeat motivations (except, I grant it, for Santa Klaus), kept coming up with villains whose defining feature was their *lack* of feelings, particularly pain and fear (he later returned to this motif in Daredevil).

It’s not that Brubaker can’t write superhero stories that take full advantage of the genre’s more unabashedly fantastic elements (he did so, quite neatly, in WildStorm’s Sleeper and The Authority: Revolution); it’s more like he set out to prove these could be vehicles for straight-up crime drama… His contemporary character-defining run on Catwoman, for example, is full of references to – and depictions of – drug abuse and underage sex work that are not exploitative so much as genuinely committed takes on these matters. At its best, the result can be touching and even heartbreaking, as it sincerely engages with topics such as substance addiction in a way that feels at least partially autobiographical.

At its worst, though, we ended up with this:

Catwoman (v3) #16

Catwoman (v3) #16

Perhaps Ed Brubaker thought this was going to be his only chance to write the sort of hardboiled fiction he cared for, so he just ran with it. Fortunately, since then his commercial success and the evolution of the editorial field have allowed him to move on to projects where he got to explore his interests through his own creations rather than impose them on franchises about spandex-wearing heroes with goofy names (even if he did use some of that freedom to do an R-rated riff on Archie).

Or perhaps it was a familiar, lingering adolescent will to prove once and for all that comics aren’t ‘just for kids.’ You could still feel this in later works – in Criminal: The Deluxe Edition, Brubaker wrote: ‘I often get asked why we haven’t collected these articles [from the issues’ backmatter] in the trade paperbacks, and my usual answer is that you don’t get to the end of a crime novel and find a bunch of articles by the author’s friends about 70s crime movies or Noir films from the 40s and 50s.’ It’s sad that the desire to emulate the ideal of a (presumably more grown-up and respected) prose novel actually means limiting what a graphic novel can provide, so I was glad to see Criminal‘s hardcovers eventually ended up collecting Brubaker’s articles as extras (although not those by his friends, as he explains, in order not to profit further from personal favors).

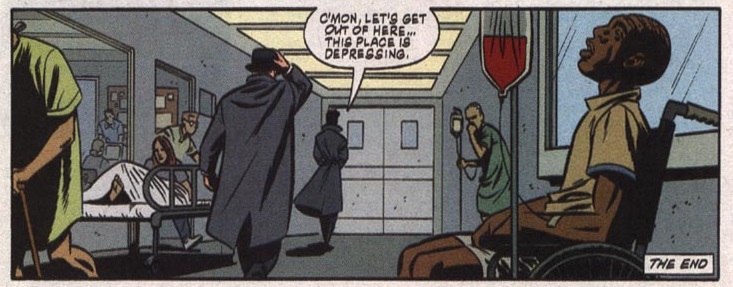

To be fair, Batman comics do have an umbilical connection to violent crime and, in any case, they have historically been eclectic enough to accommodate wide-ranging genre hybridity, so Brubaker’s approach did not always feel off-the-mark. His reboot of the Joker’s origin, the one-shot The Man Who Laughs, is a gripping thriller. His two arcs on Detective Comics – ‘Dead Reckoning’ and ‘Made of Wood’ – are right up my alley in terms of building mysteries around the specific cast and different elements of the DCU (this is also the kind of thing Jeph Loeb had recently gone for in the shockingly successful arc ‘Hush,’ but Brubaker’s approach is much, much more elegant). The Elseworlds yarn Gotham Noir, which reimagined the Dark Knight’s world through the lens of a film noir set in 1949 – starring James Gordon as an alcoholic private eye – tells a satisfying, character-driven whodunit that works by itself (although, naturally, it’s even more fun if you spot the intertextual winks to the Batman mythos).

Gotham Noir’s seedy atmosphere, in particular, seems perfectly suited to the specific pulp traditions being evoked…

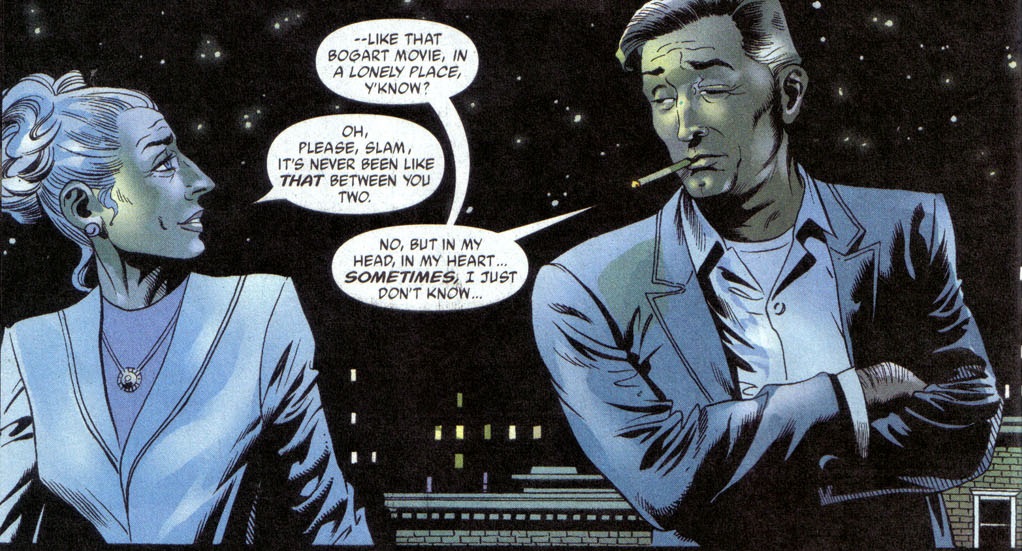

Gotham Noir

Gotham Noir

That said, I do have other problems with Ed Brubaker’s writing. The main one has to do with his tendency to tell rather than show… Now, I don’t buy into the notion that there is only one correct way to craft a narrative: as much as comics are a visual medium, words are certainly a part of it, so text can be a perfectly acceptable (even powerful) way to convey information or stimulate emotion. However, Brubaker tends to talk down to readers, spelling out every story beat, every inner conflict, even every major symbol, as if wanting to make absolutely sure we all understand how clever the story is. I suppose he could be going for complicity: perhaps his fans do feel cleverer themselves as they get the sense nothing is escaping their grasp (after all, Alison Bechdel does the same in her acclaimed autobiographical comics, so this is clearly a respected approach). Regardless, while Brubaker’s most enjoyable books have toned down this tic, it was all over his Batman and Catwoman runs, especially in contrast to the scripts of other creators in the contemporary Bat-Family series, like Kelley Puckett and Greg Rucka.

Even an incredibly wordy writer like Brian Michael Bendis manages to leave something for the readers to interpret. When he introduced a new love interest for Matt Murdoch in his Daredevil run, for instance, Bendis did it in a way that resonated with the character’s origin… It was hardly subtle, but at least he trusted fans to work out the symbolism and engage with its implications. In turn, when Brubaker followed him, the subtext became text:

Daredevil (v2) #64

Daredevil (v2) #64

(In Brubaker’s defense, this whole issue is framed like a tribute to old-school romance comics, so this could be a parody of corny writing…)

As you can no doubt tell by now, I have a very hit-or-miss relationship with Ed Brubaker’s output. I get the sensation I’ve grown up loving the same crime films and novels that inspired him, but his writing doesn’t always transcend the memory of those works. Hell, sometimes I feel more stimulated by the essays on the back of Brubaker’s books about his genre influences – like his piece on Out of the Past in Criminal #2 – than by the actual stories he writes!

Catwoman (v3) #37

Catwoman (v3) #37

More often than not, however, Ed Brubaker can truly deliver, so let’s finish by focusing on that side of his work.

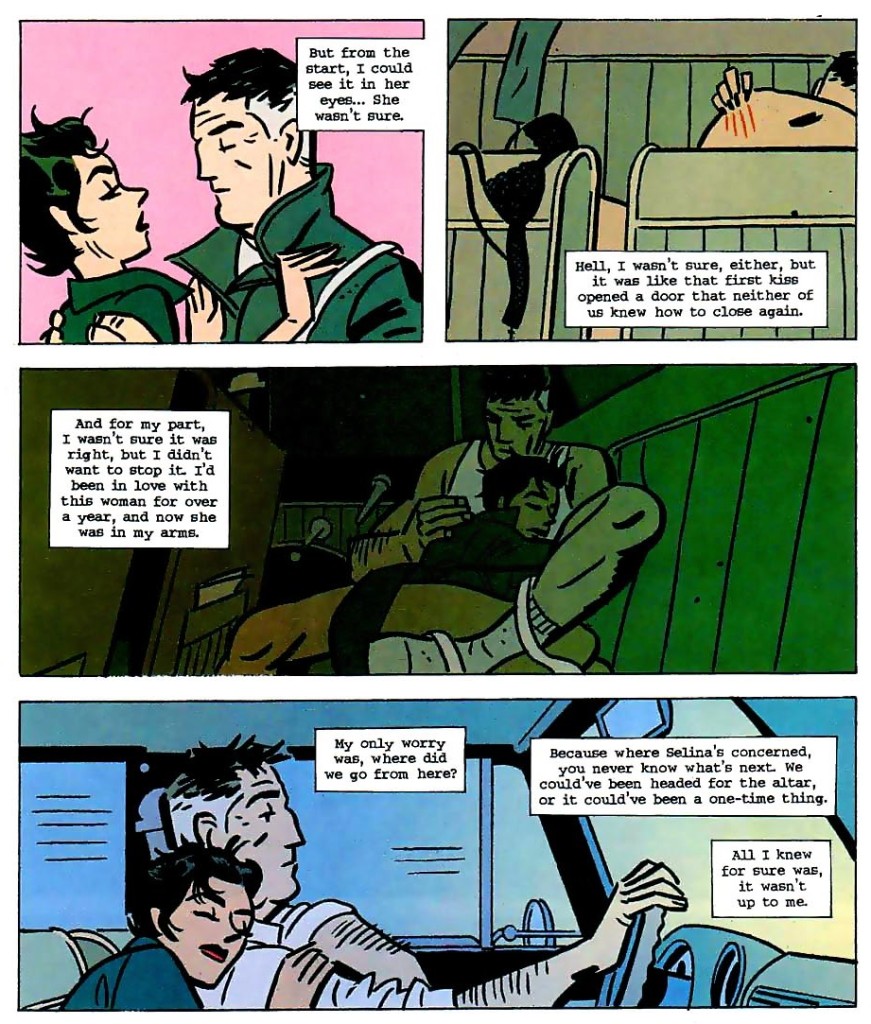

At the end of the day, Brubaker did contribute with at least two entries for the pantheon of greatest Gotham-set comics. One of them is the aforementioned run on Catwoman (at least before going downhill in its final year). For all its flaws and missteps, that seriers did reach an outstanding emotional intensity, fleshing out an extensive – largely female – cast that it’s hard not to care about. I am particularly fond of the romance between Selina Kyle and the aging private detective Slam Bradley, as well as the one between Holly Robinson and her lover Karon, full as they were with the uncertainties, ambiguities, and contradictory feelings of so many real-word relationships between broken adults who’ve been around the block.

It showed how effectively Brubaker could reframe the expectations for this kind of comic when given the right creative partners, namely artists like Cameron Stewart and Javier Pulido:

Catwoman (v3) #17

Catwoman (v3) #17

(On a meta level, the devastating thing is that what doomed this relationship were invisible editorial forces way beyond the protagonists’ control…)

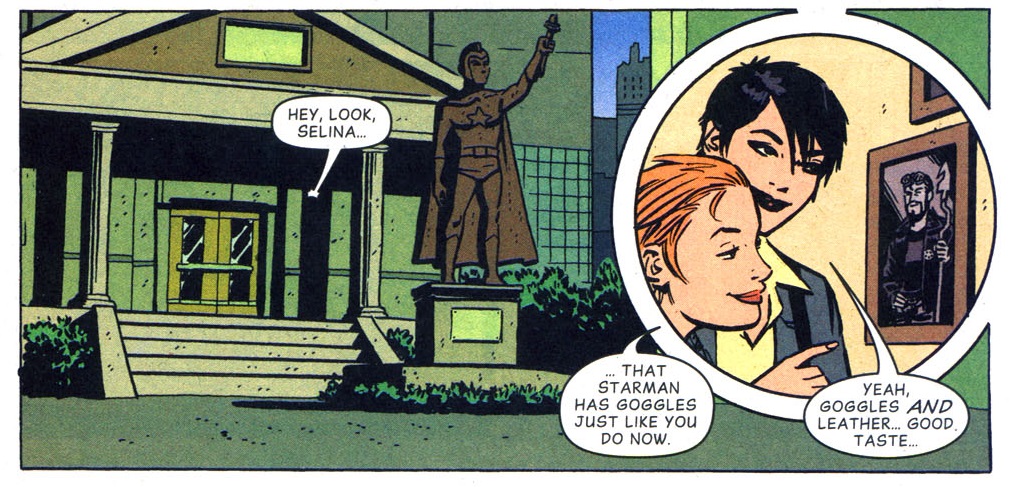

Like I said, over time Ed Brubaker’s writing appeared to have grown less ashamed of the fact that these were mainstream superhero comics and more willing to bask in the lighter side of the source material. This culminated in the wonderful Catwoman arc ‘Wild Ride,’ where Selina and Holly take a road trip through the DCU’s America. A love letter to this shared universe, ‘Wild Ride’ saw Brubaker briefly interrupt his depressing chronicles of Gotham’s drug trade to play with continuity, with series’ interconnections, and with other creators’ fun ideas, as the duo hit places such as Keystone City (home of the Flash, where Catwoman gets involved in a high-tech heist), St. Roch (DC’s version of New Orleans), and Opal City (the setting of James Robinson’s Starman, whose hip tone had probably inspired Brubaker’s own run on Catwoman in the first place).

Catwoman (v3) #23

Catwoman (v3) #23

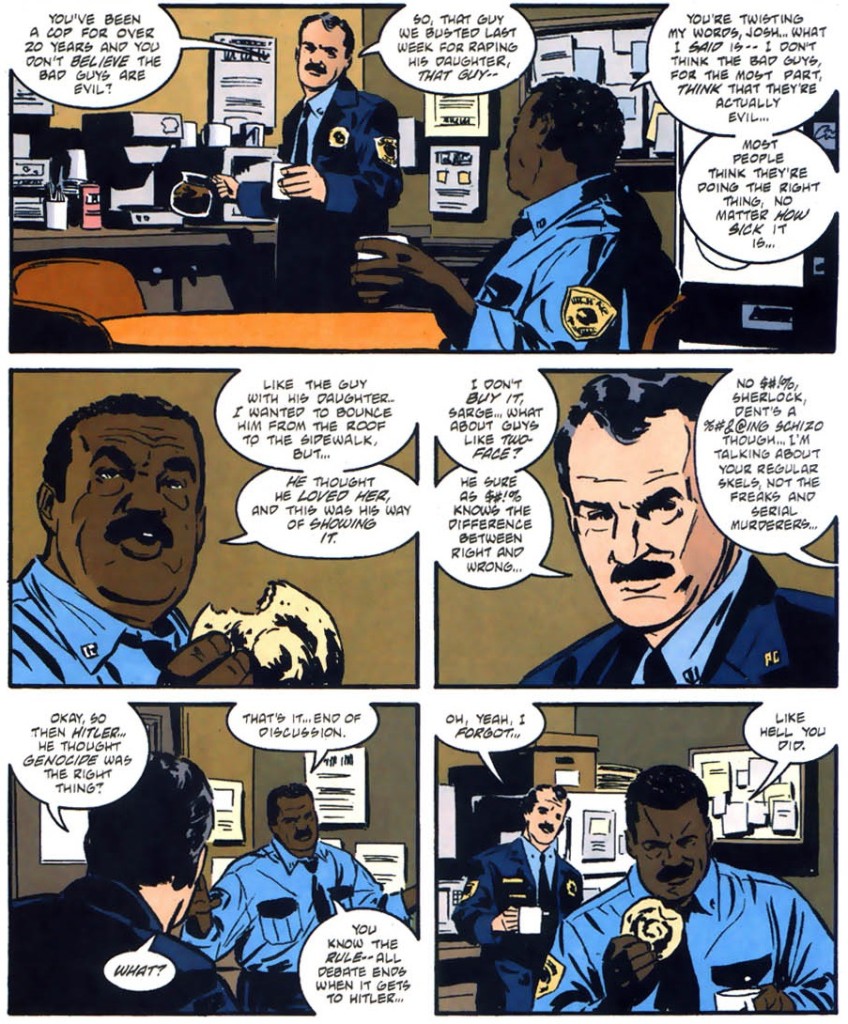

His other major contribution was Gotham Central, a police procedural set in the titular city that achieved the best of both worlds. On the one hand, it was an intelligent crime series about cops trying to operate in a corruption-riddled department – a classic set-up that isn’t exactly unrealistic (it’s not a big leap from Gotham to the Baltimore of We Own This City). On the other hand, every storyline had a couple of jarring reminders that they were also operating in a place with costumed criminals and vigilantes (whose strangeness was eerily reinforced by the deadpan artwork). GC dug into the everyday lives of regular people inhabiting the periphery of the Dark Knight’s adventures while figuring out the practicalities of policing in Gotham… For example, a civilian organization had to temp out an employee to the Major Crimes Unit so that they could have an outsider switch on the Batsignal (thus asking for Batman’s aid without officially endorsing his actions).

Ed Brubaker penned the stories about the day shift, Greg Rucka the did the ones about the night shift, and every few arcs they worked together on a joint investigation. Their styles merged surprisingly well, so that it isn’t always clear who wrote what. Crucially, Brubaker reined in his most annoying tendencies, like the (over)explanatory ‘voice-overs’ (except for issue #11), going for Rucka’s more cinematic dialogue & action storytelling approach, which resulted in some of the best work in his career. Seriously, his arc ‘Motive’ is up there with Scene of the Crime and The Fade Out as a near-perfect mystery comic… Likewise, the first issue of ‘Life is Full of Disappointments’ is a prodigy of narration-free characterization and understatement.

Plus, it was here that Brubaker wrote some of my all-time favorite Gotham moments, seamlessly incorporating the city’s idiosyncrasies into low-key conversations about good and evil:

Awesome article, as always. Thanks.

I’m not the biggest Brubaker fan either. I’m of the mind that Batman comics are litmus tests for comic writers: if you can’t write a good Batman comic, there’s not much hope for the rest of your work. I think I checked out the first few issues of his Batman run and wasn’t impressed with the urban legend take, or the return of Lew Moxon and another girl from Bruce’s past *yawn. I wasn’t impressed with Sleeper, which felt very early 2000s edgy, trench coat-cool. His work also often feels very cliche. I’m a much bigger fan of Rucka’s, even though he has his own tics.