After another season of Game of Thrones, my mind has been on sword and sorcery. I still think the series’ most engaging contributions to this genre take place on the edges of the adventure stuff, as the characters count the dead bodies and figure out how to rule the cities they’ve conquered. Yet those aspects have increasingly taken a back seat to fan service: the last seasons gave us a clearer board game structure and a greater emphasis on epic battles, as well as the apparent introduction of widespread teleportation (with everyone now able to conveniently cross huge distances in a single day or night). To be fair, Game of Thrones was never about outright dismissing genre conventions as much as it was about expanding their horizons. If anything, this TV show has bred new life into traditional fantasy elements from the start, embracing them with the straight-faced earnestness of Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood and a level of unabashed glee that seems almost reminiscent of Robert E. Howard’s prose, something I didn’t think was possible after Terry Pratchett spent decades brilliantly parodying those tropes to death.

Sure, Game of Thrones was quite deconstructionist compared to, say, the Lord of the Rings movies (not least because of the very different source material). At the end of the day, however, a large chunk of it still revolved around sandal-wearing, swashbuckling muscular knights and scantily clad babes fighting supernatural threats in a miscellaneous composite of past eras and legends. In part, the show pulled this off by taking itself extra seriously, raising the levels of grim psychological and physical violence, coming up with diverse ways of raping, castrating, and viciously slaughtering most of the cast (the same strategy used by the DC Extended Universe). Yet GoT also did it through intricate plotting, witty dialogue, nuanced characterization, and a handful of truly shocking anti-climaxes.

For those previously unfamiliar with the genre, Game of Thrones has proven that you can tell complex, thought-provoking stories using sword & sorcery tropes. For me, though, it has been a pleasant reminder of how much fun these tropes can be in the first place. After all, those backroom scenes with people forging new strategic alliances, petty betrayals, and power-hungry conspiracies are great precisely because they take place in a world of dragons and zombies, not in spite of it!

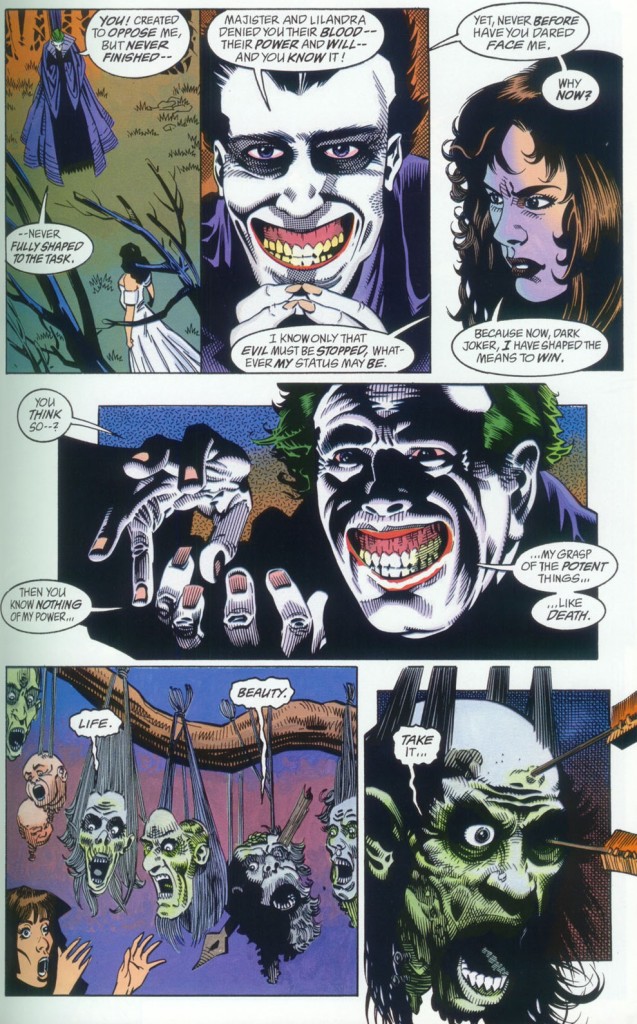

With that in mind, I decided to revisit the various Elseworlds comics in which Batman was reinvented as a hero of sword & sorcery adventure, going back to 1993’s Dark Joker – The Wild. Set in a mystical, proto-medieval land, that one-shot imagined the Clown Prince of Crime as an evil wizard and the Dark Knight as the feral, winged son of the deceased sorcerers Majister and Liandra, now on a brutal quest with the help of a mysterious woman with magical powers.

This wasn’t Doug Moench’s most inspired script: the setting and mythology were so abstract and convoluted that it was hard to engage with the story as anything more than a sequence of haunting images… Fortunately, Kelley Jones and John Beatty were in charge of the art, with Les Dorscheid doing the colors, so those images were pretty fucking impressive:

Dark Joker – The Wild

Dark Joker – The Wild

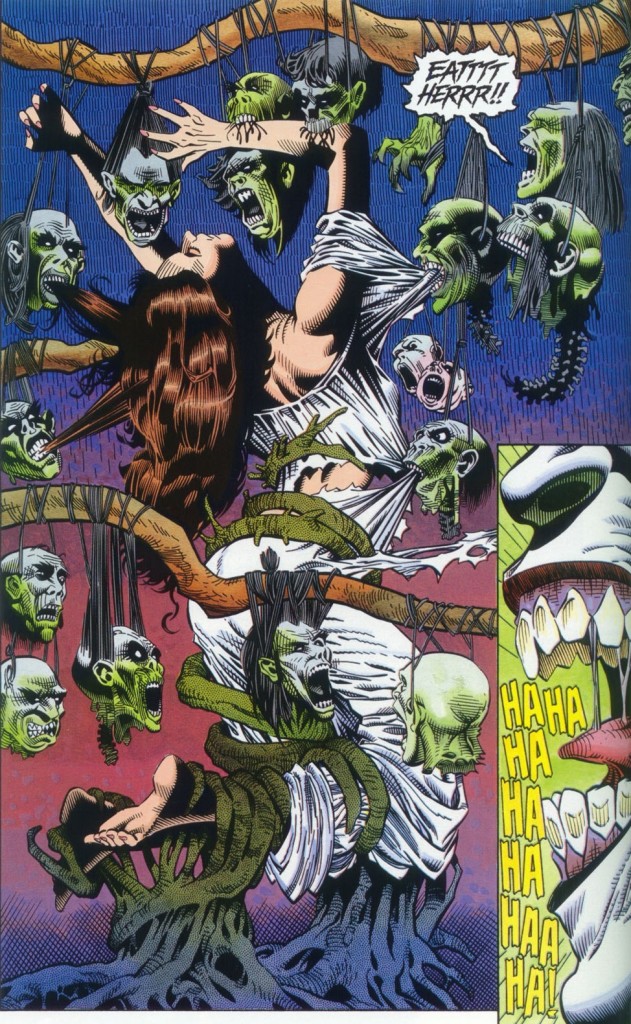

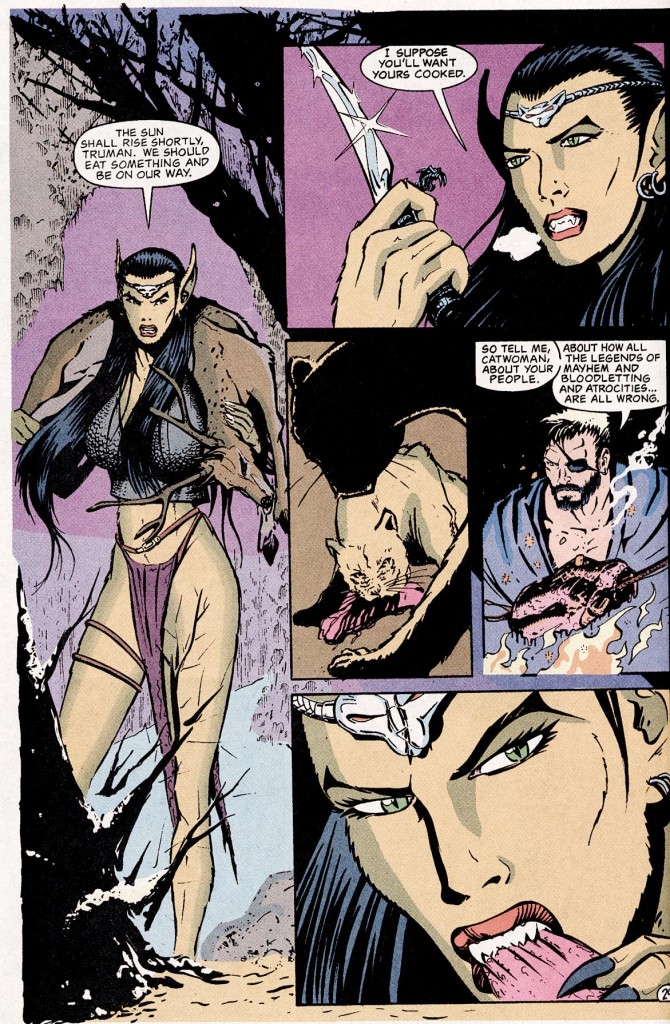

In terms of writing, I much prefer the following year’s ‘The Last Man’ (Catwoman Annual #1), penned by Christopher Priest, a smart author who a decade earlier had already sought to bring greater emotional complexity to the Conan comics. This issue, part of DC’s strand of Elseworlds annuals that year (which also gave us a pirate Batman and a samurai Robin), takes place in an alternate 1275 AD, after the emperor of Augustonia declared war on the House of Selene, accused of idolatry, witchcraft, murder, blasphemy against the church and state, consuming the flesh of infants, and drinking the blood of martyrs. The war is carried out by the emperor’s son, the Batman-looking Timon, Vicar of the House of Lords, determined to slay the wicked savages.

After facing the fierce leader of the House of Selene – Rä’s al Ghül, the Cat-Man – Timon is rescued by his foe’s fur-covered daughter, slowly coming to terms with the fact that perhaps you shouldn’t believe everything you hear about other cultures, nor should you pass harsh judgement before making an effort to understand them. In other words, after setting the stage for a formulaic confrontation, the comic shakes things up by exposing the manly hero as a bigoted brute and his righteous crusade as essentially rooted in blind obedience.

Like Game of Thrones, though, ‘The Last Man’ seems less interested in defying the genre than in crafting a satisfying yarn within its boundaries. Priest has fun with the pompous speeches (‘May the Devil and his minions feast on your entrails.’) and fake religious logic (‘Selenes are no higher than rats or carrion! They have no souls and no sure welcome in paradise! You should be grateful such lack of humanity bars you from eternal damnation as well!’). He also creates a fine character dynamic between these versions of Batman and Catwoman/Talia, as they grow innevitably closer while journeying together…

Catwoman Annual #1

Catwoman Annual #1

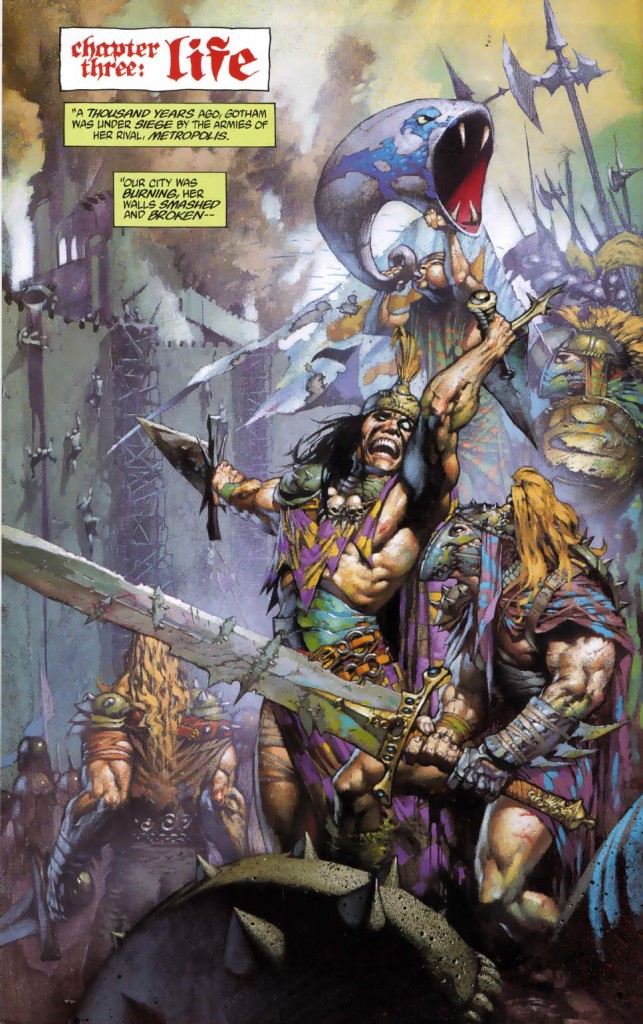

In 1996, we got a batch of this kind of tales thanks to another conceptual link running through DC’s annuals – under the banner ‘Legends of the Dead Earth,’ each issue told a story from the point of view of a post-Earth future in which DC’s characters had become misremembered legends. In practice, the stunt just meant that we got a bunch of Elseworlds comics, yet this time around more creators chose to go with the sword & sorcery route for the Batman-related books…

Dennis O’Neil and Barry Kitson did it in ‘Night’s Fall’ (Azrael Annual #2), which included an interesting fantasy retelling of the ‘Knightfall’ crossover, but it was sadly lost among the series’ usual barrage of bulky art, groan-inducing dialogue, and nonsensical plotting. By contrast, at the time Alan Grant wrote two outstanding takes on the genre: ‘King Batman’ (Shadow of the Bat Annual #4) and ‘Executioner’ (Legends of the Dark Knight Annual #6).

The former, smoothly drawn by Brian Apthorp and Stan Woch, is narrated by a being at the end of the universe who is recording ‘thought-images’ directly onto subatomic particles in the hope that one day, in a new universe, someone will somehow find his message and decipher it. He identifies himself as ‘the end result of a myriad of evil thoughts and countless evil deeds’ – in other words, he was the one responsible for Evil’s triumph and the subsequent destruction of the universe… And now, as he relives the path that brought him here, he wonders if he can still change history by mentally pushing quantum node points.

This is just the framing device, though. The main story actually involves an army of lizard-people mounted on dinosaurs, led by the ruthless Ophos Arkayos, who has been conquering Earth:

Shadow of the Bat Annual #4

Shadow of the Bat Annual #4

Arkayos’ army is about to invade Nu-Gotham, where the lizards can access launch pads and take their war into space. In his way stands the city’s king, who is also a hero inspired by and modelled on the Caped Crusader. At first, King Batman seems to be little more than a slight variation of the original, albeit one armed with a photonic flash that can disrupt villains’ memory, bringing all of their evil to the attention of their conscious mind at once. Alan Grant, however, has a few more tricks up his sleeve, so he manages to provide a number of neat twists.

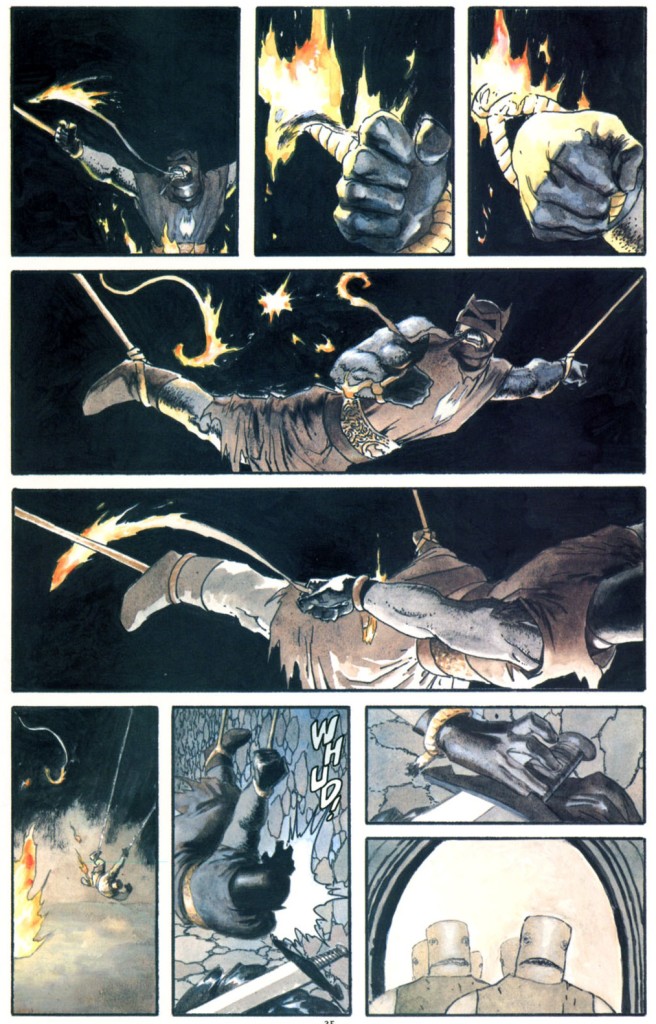

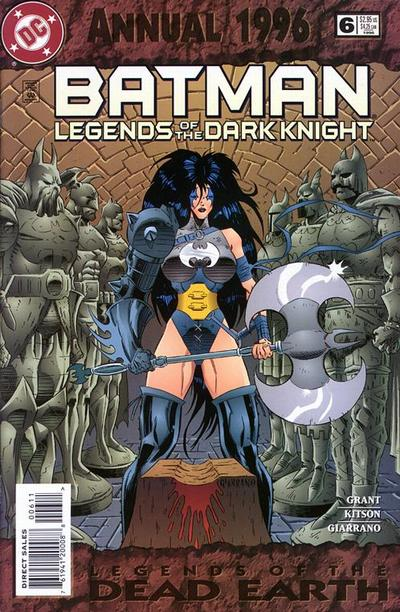

‘Executioner’ has even more of a sci-fi vibe, yet with enough medievalism thrown in to justify its inclusion here. It concerns a society in which Batman is the hereditary title of the official executioner, killing in the name of the law and thus practically eradicating crime from this version of Gotham. In fact, the story takes place on another planet, five hundred years after humans crash-landed on it and founded this civilization (so the palace is decorated with allusions to other DC heroes, like the Flash, Green Lantern, and Superman). When the latest Batman kills himself, his daughter, Kathy Kane, takes over the mantle, but while looking into the motives behind her father’s suicide she uncovers a sinister conspiracy that sheds new light upon the city’s law enforcement strategy.

Alan Grant shares plot credits with Barry Kitson on this one, but the art is by Vince Giarrano, who – like Kitson – has a propensity for exaggerated costumes and female busts, encapsulating some of the worst excesses of the ‘90s. As a result, his Kathy Kane looks like a Huntress dominatrix role-playing game:

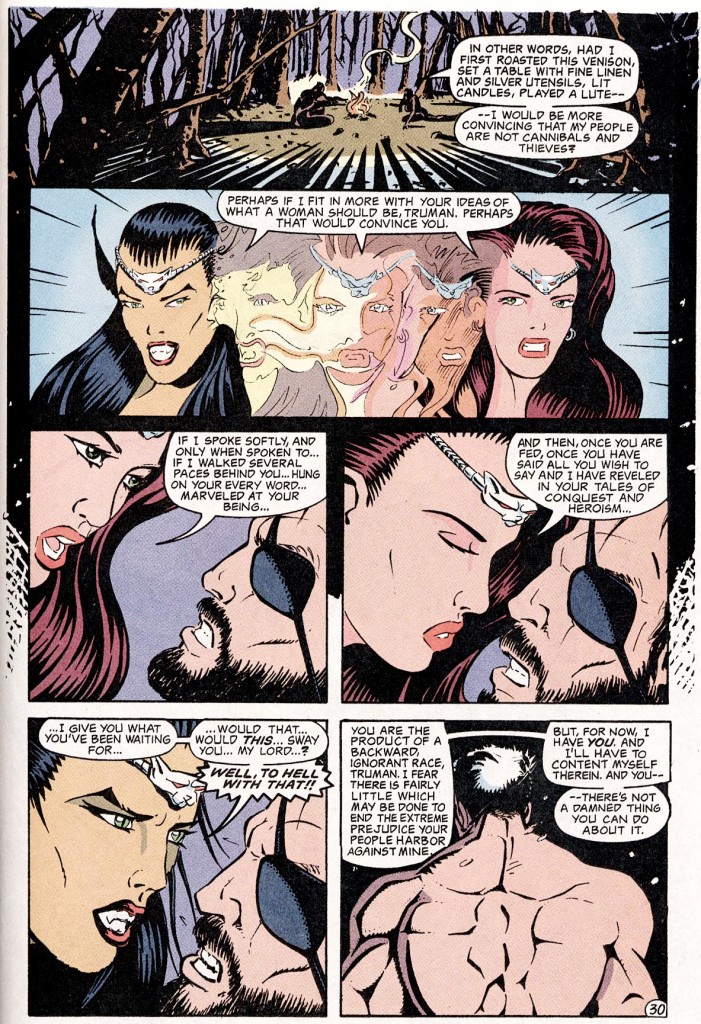

Grant returned to the idea of combining Batman iconography with fortress cities, old-fashioned cloaks, and contradictory time references in the one-shot Batman & Demon: A Tragedy. The book’s high concept is basically a fusion between the characters of Bruce Wayne and Jason Blood – Bruce believes he is allergic to moonlight (owing to an orbital eccentricity, the moon shines full every night in this Gotham), but he is in fact unknowingly hosting Etrigan, the rhyming bat-demon, who goes around slashing criminals during nighttime. It’s a violent gothic tale that lives up to its title, finishing on a poignantly tragic note.

This time around, the illustrations are by Jim Murray, who comes up with jaw-dropping designs for Poison Ivy as a sexy alchemist, Killer Croc as a scary gang boss, and Catwoman as a badass occult fighter. Murray seems to be suitably channeling Frank Frazzetta’s classic covers for pulpy paperbacks and hard rock albums:

Batman & Demon: A Tragedy

Batman & Demon: A Tragedy

Finally, a couple of Elseworlds specials reimagined Batman as a British knight in the Middle Ages, caught between wizardry and chivalry. Bob Layton’s and Dick Giordano’s two-part Dark Knight of the Round Table drew on Arthurian legend and featured some interesting characterization by showing Bruce of Waynesmoor driven by thirst for vengeance against both Mordred and Arthur Pendragon. However, burdened with pedestrian art and storytelling – including exposition-heavy dialogue – the resulting comic was pretty much a mess (and not even a fun mess, like Guy Ritchie’s King Arthur: Legend of the Sword!).

More successfully, Mike W. Barr (the writer of Camelot 3000) penned the clever graphic novel Dark Knight Dynasty, in which three iterations of the Caped Crusader battled the immortal Vandal Savage in the past, present, and future. The past sequence, painted by Scott Hampton, follows the trial of the knight templar Joshua of Wainwrigth, who tells a fantastic story about a magical castle in 1222 AD… And, because this is a Batman comic by Mike Barr, you can bet there is at least one sequence with our hero ingeniously escaping from a deathtrap:

Dark Knight Dynasty

Dark Knight Dynasty

(Still, it doesn’t beat the final third of the book, in which Batman’s descendant fights Vandal Savage in outer space, with the aid of a monkey Robin!)

All in all, I guess the main lesson is that, no matter how much you twist Batman as a character, you know that sooner or later he is going to end up loudly kicking someone in the face:

Dark Joker – The Wild

Dark Joker – The Wild

Shadow of the Bat Annual #4

Shadow of the Bat Annual #4

NEXT: More kicks in the head.

I’ve been reading quite a bit of Sword-and-Sorcery stuff lately, mainly in preparation for my entry into Discworld (yeah yeah, I know it’s not necessary and the parody-heavy books aren’t anyone’s favorites, but whatever). Some of it is better than others, but I haven’t found anything I’d bother rereading yet.

Oh man, Legends of Dead Earth… IMO, it’s quite possibly DC’s most craven attempt at cashing in on Gaiman’s Sandman, by way of turning it into a big summer crossover (or the closest thing that could also try to mimick the Story-About-Stories concept). Inevitably, I find the framing device of each annual more interesting than the actual story, though that might just be because I’m in my “What comes after humanity’s died? And other morbidities” phase.

I hadn’t thought about it, but you’re dead right… ‘Legends of the Dead Earth’ was totally part of DC’s ‘Sandmanization’ phase!

As for Discworld, if you’re looking for an on-ramp, I recommend Guards! Guards! or any of the ones mentioned at the end of this