If you read last week’s post, you know I’ve been discussing comics that expanded H.G. Wells’ classic novel The War of the Worlds.

Today I want to start with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Alan Moore’s and Kevin O’Neill’s fun series about a Victorian team of anti-heroes made up of old public domain characters. Much of LOEG’s second volume (originally a six-issue mini-series published in 2002-2003) revolved around Wells’ Martian invasion, which suited both the comic’s initial conception (digging up the origins of pulp fiction by reveling in turn-of-the-twentieth-century fantastic literature) and its political motifs (satirizing the monstrous side of the British Empire).

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #1

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #1

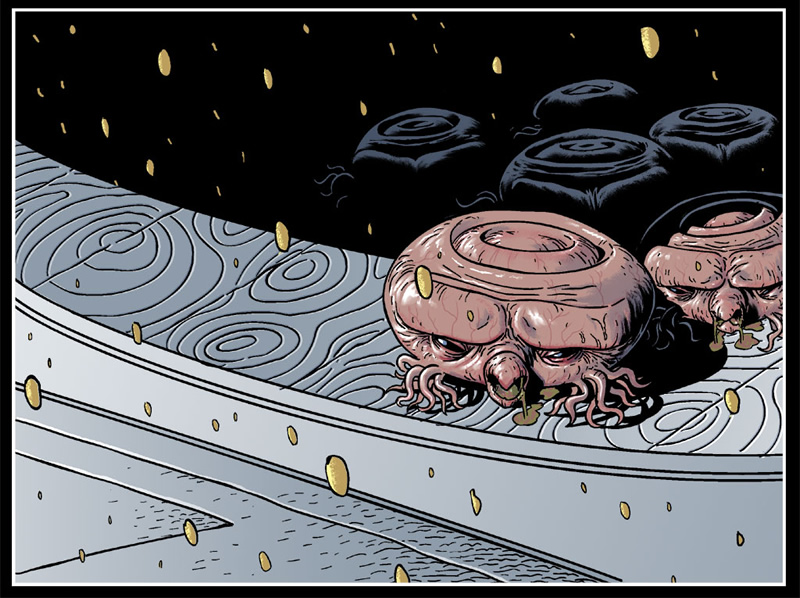

In line with the series’ notion of connecting disparate works into a single, intricate continuity, Moore and O’Neill integrated The War of the Worlds on a vast tapestry, kicking things off with a prelude on Mars that tied Wells’ novel to Edwin L. Arnold’s Lieutenant Gullivar Jones: His Vacation and to Edgar Rice Burrough’s Barsoom stories featuring John Carter. The whole thing may sound too esoteric, but O’Neill successfully brought it to life as an eerily dreamlike grand adventure through glorious splash pages like the one above.

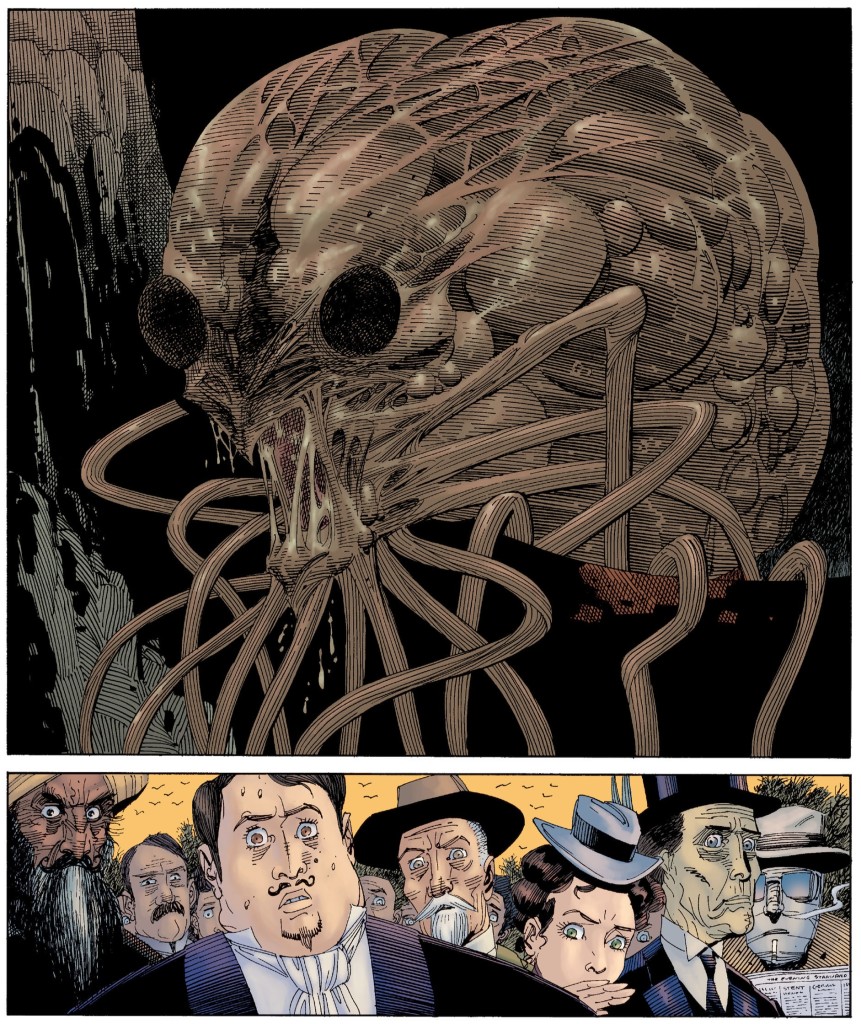

By the time we got to the second issue, the main action became deeply entangled with H.G. Wells’ narrative, albeit seen from the point of view of the protagonists of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. This applied both to peripheral details (even the newspapers headlines were taken from the book) and to key scenes like the expedition into the initial crater by Stent, the Astronomer Royal, closely depicting the lead-up to the first massacre. Some of the dialogue is reproduced verbatim – for example, we catch a glimpse of the original (unnamed) narrator’s conversation with his neighbor in one of the backgrounds (‘What ugly brutes!’).

And, needless to say, Kevin O’Neill hauntingly visualizes the Martians’ horrific looks…

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #2

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #2

That said, as usual with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (and contrary to what some critics say), we get much more than the mere pleasure of recognition across media.

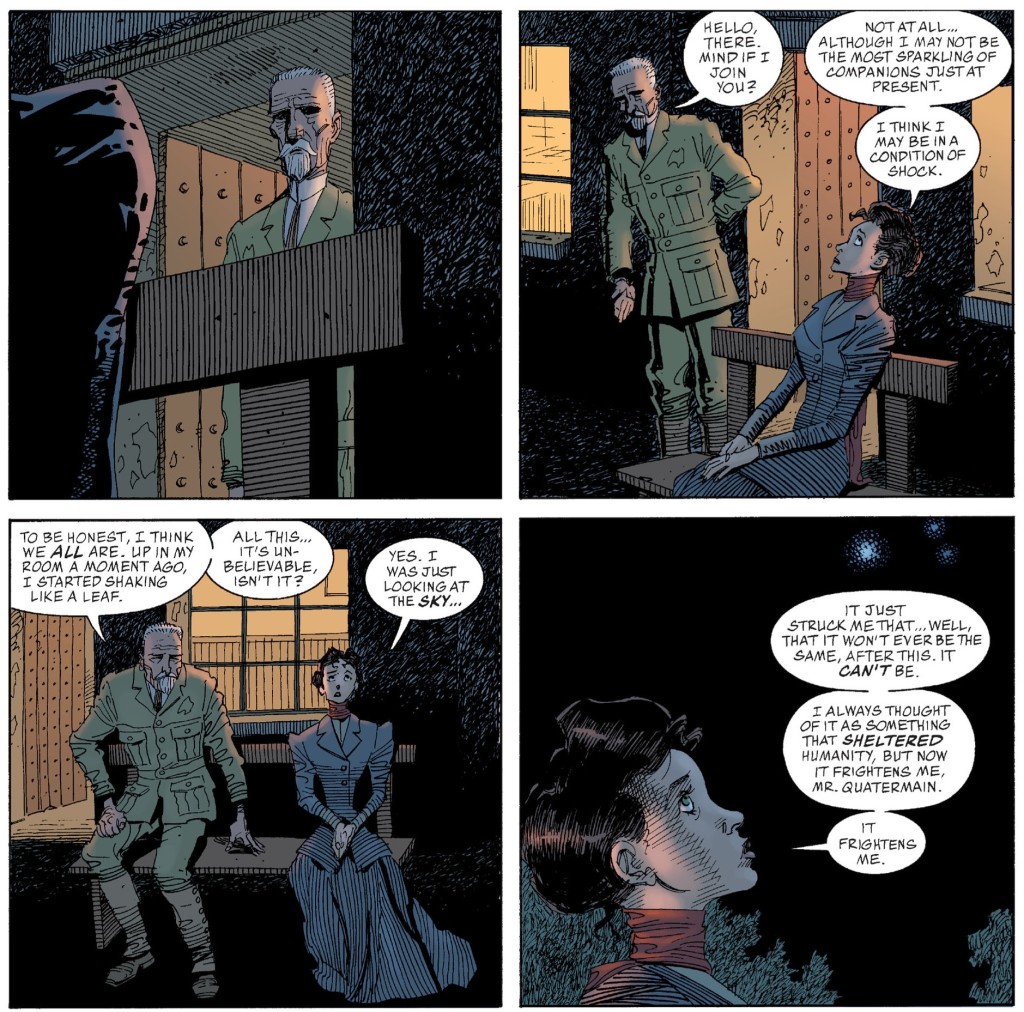

For one thing, Alan Moore is a master of characterization, so he skilfully milks the invasion’s dramatic potential by showing us how each of the protagonists would react to such a world-shattering turn of events. Besides fleshing out the series’ leads, Moore slows down the action just enough to convey the overall weight of the situation, thus recapturing the ‘lost innocence’ atmosphere that permeates H.G. Wells’ novel…

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #2

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #2

While shifting perspectives, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen reveals supposedly hidden aspects of the story. It turns out the shot that destroyed one of the tripods on the novel’s twelfth chapter was fired by Captain Nemo. The Martian red weed is then revealed to be an anti-submarine weapon (suggested by the Invisible Man) deployed specifically against the Nautilus.

Most notably, what ultimately kills the aliens is not a natural strain of bacteria, but a genetically engineered hybrid of anthrax and streptococcus designed by another H.G. Wells creation, Doctor Moreau, and deliberately fired against the Martians by the British forces. Bear in mind that this retcon doesn’t necessarily contradict the original text, whose subjective narrator presented the natural infection explanation as a mere hypothesis. Thus, Alan Moore applies to The War of the Worlds the kind of radical-yet-faithful revisionism he had previously applied to comics like Marvelman, Swamp Thing, and The Spirit (and even to the Joker’s Red Hood origin in The Killing Joke).

Thematically, though, this new version seems to go against the underlying spirit of Wells’ book, which rested on two humbling gestures. On the one hand, the text followed the perspective of marginal players on the sidelines, helplessly witnessing the main action without controlling it (this is where much of the horror stemmed from), unlike LOEG’s leads, whose choices shape the invasion’s final outcome. On the other hand, the point of Wells’ ending was precisely that the humans weren’t able to defeat the Martians – the subtle double meaning in the title was that the worlds at war weren’t just those of humans and aliens, thus subverting humanity’s sense of self-importance.

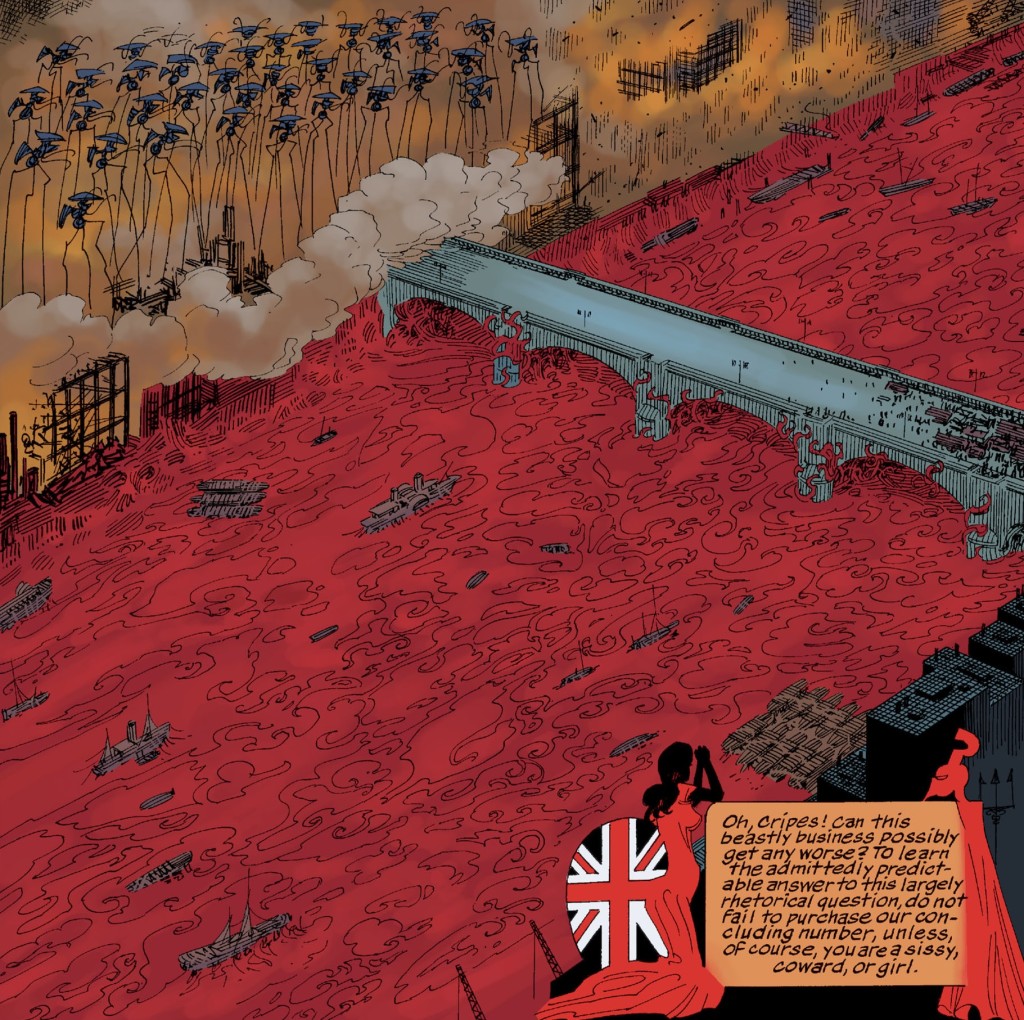

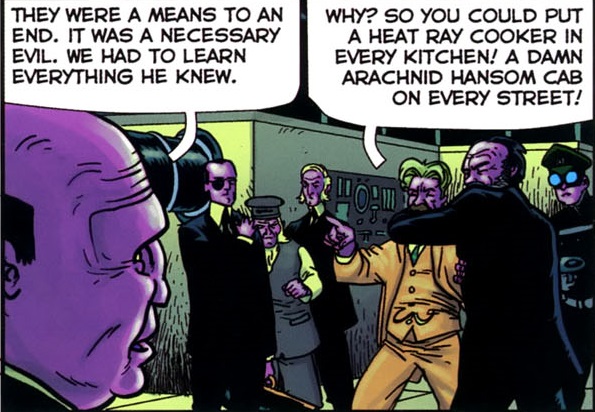

Regardless, I suppose you could argue that The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen’s reinterpretation does preserve some of the slant of the original work, since the revised story is itself an allegory about imperial ruthlessness. After all, not only do we see British authorities gleefully developing – and ultimately resorting to – biological warfare, but we get a taste of their cynical relation with public truth: ‘Officially, the Martians died of the common cold. Any humans died of Martians.’ Plus, as was typical of LOEG’s earliest volumes, every aspect of the comic seems designed to mock Victorian values, right up to each chapter’s closing blurbs…

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #5

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #5

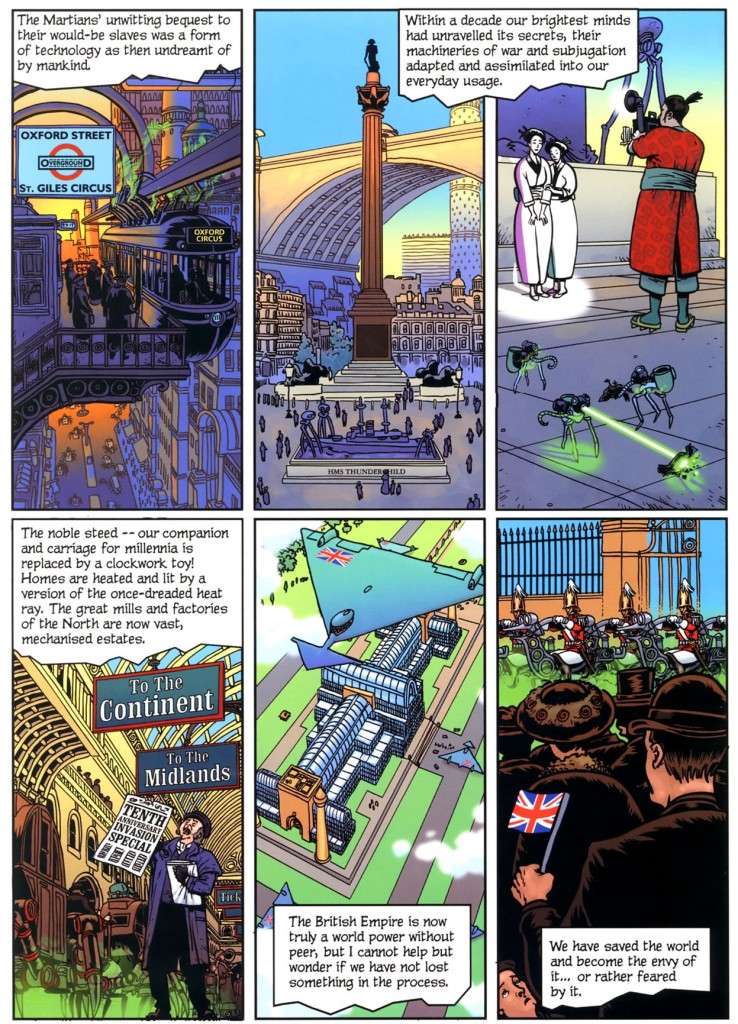

Around the time that this comic first came out, we got a different project expanding H.G. Wells’ seminal work – not sideways, like LOEG, but by moving forward chronologically in the form of a direct sequel, like Marvel had done in the seventies. Ian Edginton’s and D’Israeli’s Scarlet Traces was originally published online before being serialized, in 2002, in Judge Dredd Megazine #16-18 and later collected in a Dark Horse hardcover (more recently, the series and its sequels have also been collected by Rebellion). Set in 1908, this comic imagined the aftermath of The War of the Worlds in a way that departed from Wells’ hopeful ending – instead of humanity coming together and, humbled by its recent experience, tempering its arrogance with a more peaceful, progressive outlook, the Martians’ defeat renewed the survivors’ old sense of purpose… because it was just as easy to believe the aliens had been killed by microscopic bacteria than to see it as divine intervention, i.e. as proof that God was on our side.

Notably, unlike Amazing Adventures, which suggested that twentieth-century history had carried on in much the same way as in our timeline after the Martians’ failed invasion, Scarlet Traces assumes the world in general – and Britain in particular – has been profoundly shaped by those events, especially due to the encounter with alien technology. This is the starting point for a clever bit of speculative fiction, taking into account the turn of the century’s New Imperialism while also serving as a springboard for a bunch of nifty steampunk landscapes:

Scarlet Traces

Scarlet Traces

As you can see, like Kevin O’Neill, D’Israeli evokes a certain type of Victorian aesthetics while providing a distinctive visual style that is clear yet unrealistic (which is not to say that the depicted creatures and machinery aren’t carefully conceived, as demonstrated by the fascinating sketches at the end of the hardcover edition).

His interpretation of the Martians is strikingly different from O’Neill’s – as well as from Howard Chaykin’s and Manuel Garcia’s – while nevertheless managing to remain faithful to H.G. Wells’ description:

War of the Worlds (2006)

War of the Worlds (2006)

Likewise, Ian Edginton gets Wells’ voice but he doesn’t stick to mere pastiche. For one thing, the quaint prose is often interspersed with folksier dialogue. Moreover, rather than replicating the original’s formula by telling another war story, Edginton chose to open this new saga with a classic conspiracy thriller (a proven narrative device for exploring alternate realities). He also added multiple interesting layers of world-building, for example speculating that the sudden jump in terms of mechanization would take a particular toll on industrial Scotland, where the ensuing mass unemployment was bound to generate resentment.

In a move comparable to LOEG’s, despite subverting the spirit of The War of the World’s epilogue, Scarlet Traces stays true to H.G. Wells’ critique of the British Empire’s aggressive power and self-entitlement. The notion of a postwar nation deploying the technology of its former adversary also brings to mind the role of Nazi scientists in the United States after World War II – or, more generally, the public’s willingness (still today) to indulge in comfort and consumer goods with little regard for how they were produced…

Scarlet Traces

Scarlet Traces

Edginton and D’Israeli seem to have struck creative gold with this series, bringing to life a truly captivating timeline, visually as well as thematically. They followed it up with a straight-up adaptation of War of the Worlds and, in 2006, with a four-issue sequel, Scarlet Traces: The Great Game.

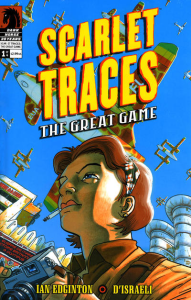

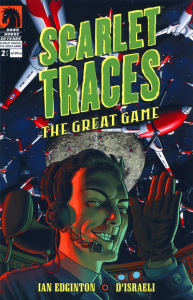

Building on the conclusion of the previous volume, this sequel jumped to the 1940s, when the British Empire was still at war with the Martians. By then, global technological superiority and the protracted armed conflict had unleashed the UK’s authoritarian impulses, to the point where Oswald Mosley was now Home Secretary and George Orwell was in an internment camp (a throwaway line that pays off with a neat visual cameo near the end). This time around, we followed intrepid photojournalist Charlotte Hemming as she investigated yet another sinister conspiracy. She was quite a charismatic character, even though, once again, the main attraction was the sheer process of gradually uncovering this world’s politics, society, historical deviations, and retro-sci-fi imagery…

Scarlet Traces: The Great Game #1

Scarlet Traces: The Great Game #1

Honestly, I’d say The Great Game makes for an even more satisfying read than the first Scarlet Traces. The political intrigue is sharper (even if you ignore the obvious nudges to the Bush/Blair era’s War on Terror) and D’Israeli delivers some stunning battle scenes on Mars and outer space. Plus, while not going as far as The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen’s nerdy obsessiveness, the book pays tribute to classic science fiction by sneaking in all sorts of subtle references to stuff like Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future and The Adventures of Tintin, not to mention H.G. Wells’ own The First Men in the Moon.

Hell, the covers smack of Dan Dare’s pulpy military space adventure vibe, combined with WWII posters:

After a lengthy hiatus, we finally got new Scarlet Traces comics in 2016, when they became a recurrent strip on the pages of 2000 AD. The first arc, ‘Cold War,’ which moved the action to 1968, revolved around a spy mission to Venus, still under Martian occupation (since the end of War of the Worlds). For all its populist, in-your-face allusions to topics like racism and the refugee crisis, though, the new iteration of Scarlet Traces essentially boiled down to a much more traditional fantasy adventure series (albeit with epic stakes), its plot a string of genre clichés ultimately elevated by D’Israeli’s eccentric, rubbery artwork and increasingly experimental colors.

That said, at least the ‘Home Front’ arc brought back Charlotte Hemming, which remained a joy to read about. Moreover, Ian Edginton and D’Israeli sure know to pander to their fanbase with a steady supply of (unobtrusive) geeky Easter Eggs…

2000 AD #2023

2000 AD #2023

As if all this wasn’t enough, Edgniton invited other people to play in this sandbox, editing a prose anthology last year with short stories by – among several others – fellow 2000 AD alumni Emma Beeby and I.N.J. Culbard. And we’ve been promised more Scarlet Traces comics soon!

At the end of the day, while I didn’t care for every single beat in the series, I can’t help but appreciate the overall Scarlet Traces saga, which has truly developed The War of the Worlds into a sprawling mythology populated with a richly diverse cast. In particular, the fact that – like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and even, in its own peculiar way, Don McGregor’s run in Amazing Adventures – the result has echoed and commented on the various conflicts humanity has gone through since 1898 seems like a logical extension of H.G. Wells’ own pacifist concerns.

Huh. I must admit I was kind of expecting for a reference to Roy Thomas’ ‘Superman: War of The Worlds’ Elseworlds book.

I was more interested in comics that work as proper sequels or spin-offs to the original novel rather than full-blown reimaginings…. But you’re absolutely right that I should’ve given a shout-out to Superman: War of the Worlds, if nothing else because of Michael Lark’s beautiful designs!