All kinds of people have written Batman stories. Not just people: even Snoopy has done it. But one author has the particularity of having written both the most critically acclaimed Batman comics of all time, and the most universally reviled.

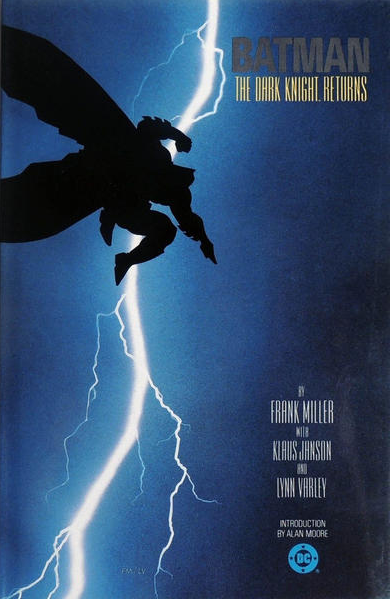

Frank Miller first became, inarguably, one of the most influential voices in the evolution of Batman with 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns (DKR).

Together with Watchmen, DKR brought mainstream attention to adult-oriented superhero deconstructionism, kick-starting decades of grim & gritty copycats. And just like Watchmen, it remains a gripping read after all these years – and one that can appeal even to those who are not fans of the genre – because of how well-crafted and ‘modern’ it feels (if unabashedly rooted in 1980s’ angst). However, both works are even more powerful if you’re familiar with their background.

Together with Watchmen, DKR brought mainstream attention to adult-oriented superhero deconstructionism, kick-starting decades of grim & gritty copycats. And just like Watchmen, it remains a gripping read after all these years – and one that can appeal even to those who are not fans of the genre – because of how well-crafted and ‘modern’ it feels (if unabashedly rooted in 1980s’ angst). However, both works are even more powerful if you’re familiar with their background.

In the case of DKR, the book redefined the depiction of Batman to such a degree that it is easy to miss how groundbreaking it was. Although a handful of creators in the previous 15 years had given the Caped Crusader an increasingly somber tone, he remained a fundamentally underwritten character. More importantly, Frank Miller’s approach stood in stark contrast to Batman’s incarnation in the campy 1960s TV show that was still quite resonant in popular imagination. Instead of a simple, goofy, friendly, masked Adam West, we got this man:

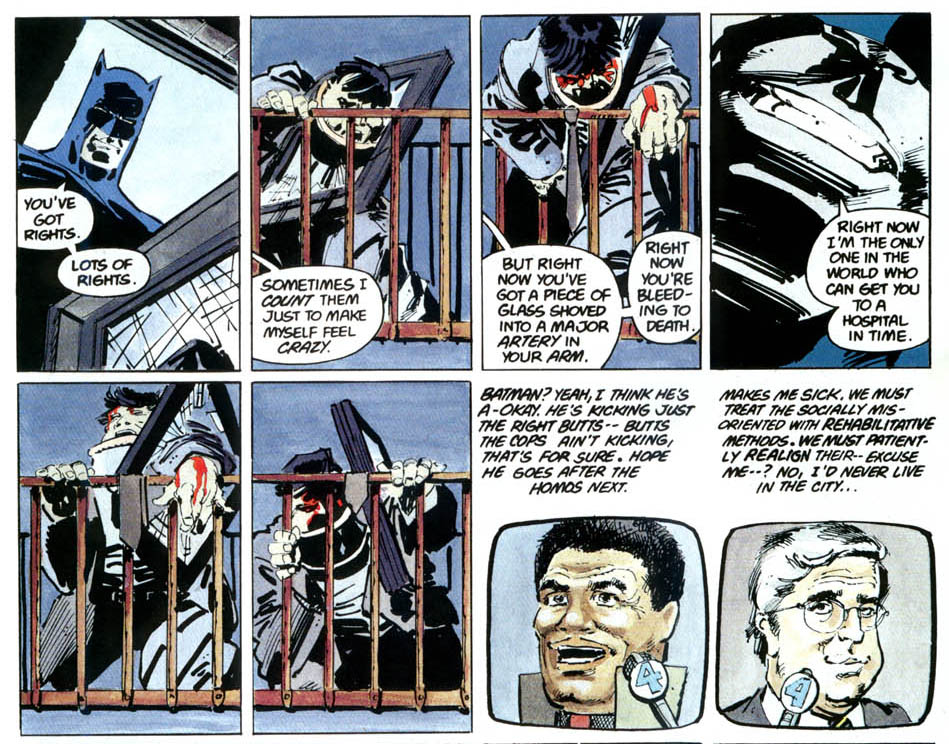

In the opening pages of DRK, we meet an old, mentally unstable Bruce Wayne, who retired his Batman persona and now drowns it in alcohol. Soon, we see him back in his suit and back in the street beating up punks, because that’s how you deal with midlife crisis… It’s not that Miller engaged with the psychological and ideological implications of Bruce’s compulsion in a particularly sophisticated way, but the fact that he addressed them to such an unprecedented extent was gratifying enough. More than condone or mock Batman’s actions, DKR gleefully rubs in our faces how cool and satisfying and at the same time problematic our infatuation with this nutjob can be.

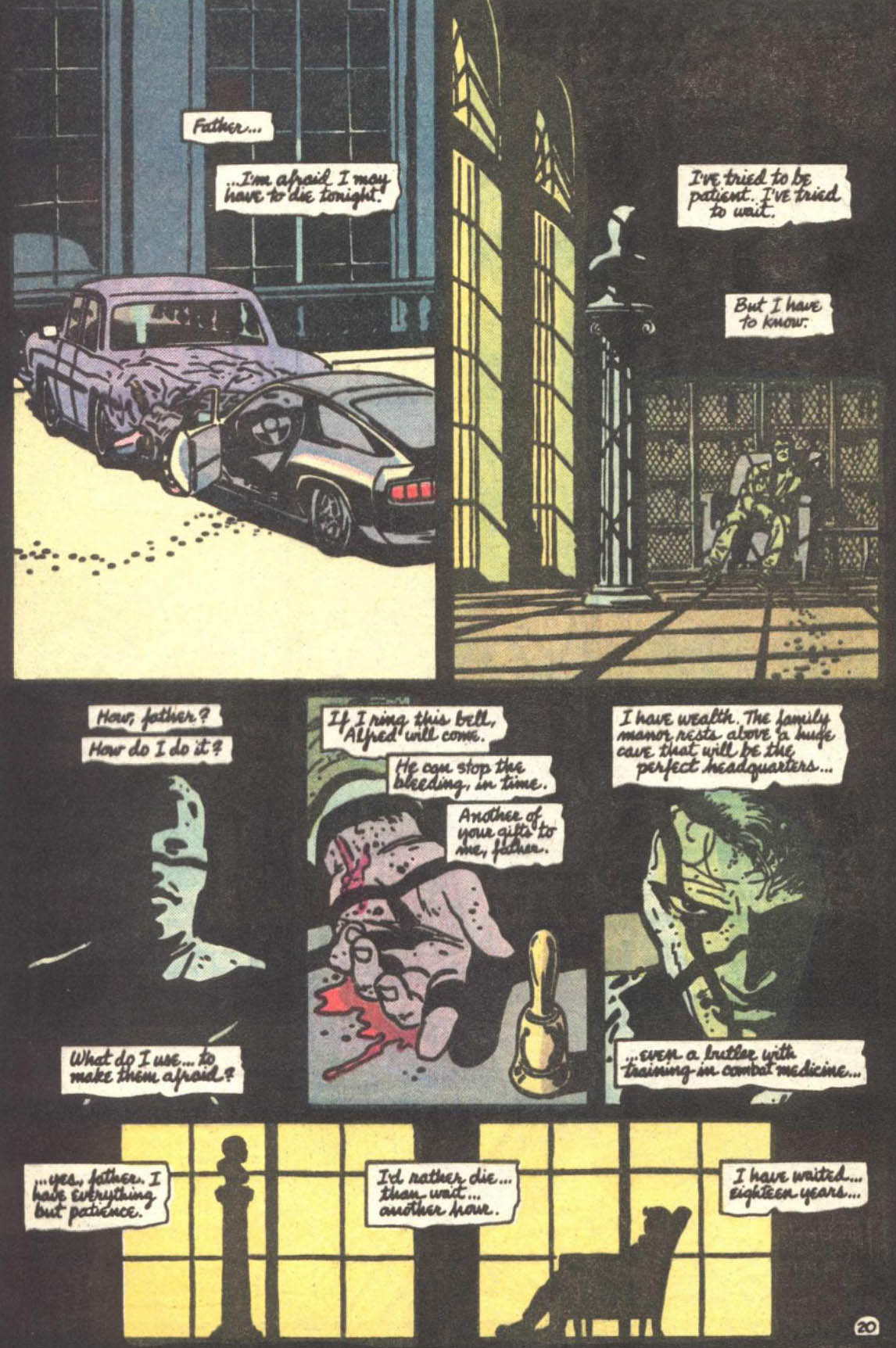

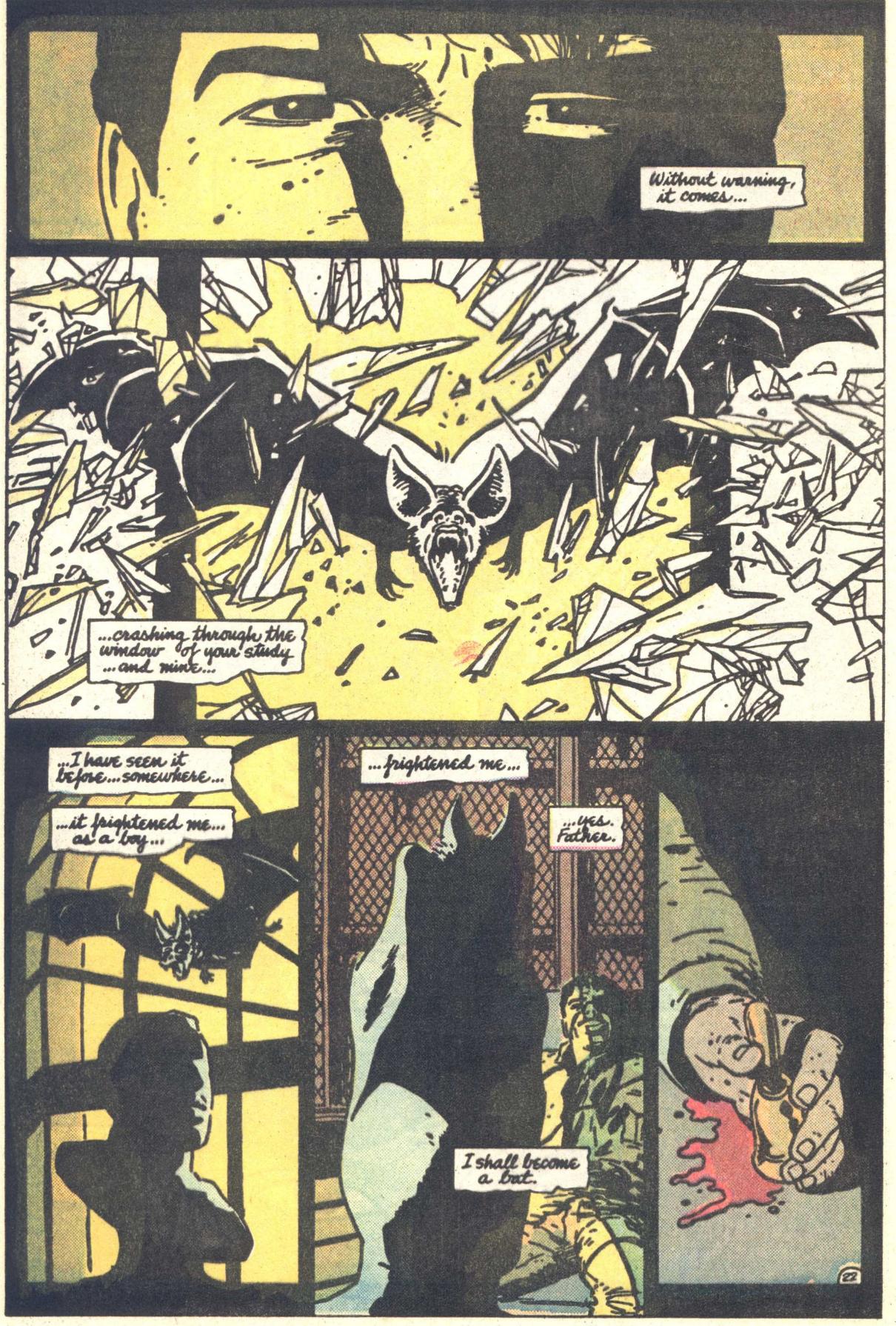

And it’s not just the taboo of treating the Dark Knight this way, it’s the notion that a Batman comic can be drenched in contradictory politics and graphic violence. It’s the catharsis, after decades of bat-and-mouse games, of reading the final showdown between Batman and the Joker, in a fight to the death. It’s the whole ‘this ain’t your daddy’s funny pages’ attitude that Miller brilliantly encapsulates with in-your-face visual touches like using the traditionally harmless batarangs as razor blades or revisiting the moment Bruce Wayne first decided to become Batman as he saw a bat flying through an open window… in DKR, when Bruce decides to once again don the cape and cowl, we see a bat break through the damn glass!

And it’s not just the taboo of treating the Dark Knight this way, it’s the notion that a Batman comic can be drenched in contradictory politics and graphic violence. It’s the catharsis, after decades of bat-and-mouse games, of reading the final showdown between Batman and the Joker, in a fight to the death. It’s the whole ‘this ain’t your daddy’s funny pages’ attitude that Miller brilliantly encapsulates with in-your-face visual touches like using the traditionally harmless batarangs as razor blades or revisiting the moment Bruce Wayne first decided to become Batman as he saw a bat flying through an open window… in DKR, when Bruce decides to once again don the cape and cowl, we see a bat break through the damn glass!

DKR punched Batman comics in the balls and they’ve been in its awe ever since. The image of pearls falling during the Waynes’ murder has become a recurrent visual cue. The notions that Batman is a psychopath and that he can kick Superman’s ass have been taken for granted by many creators. Offhand allusions to Jason Todd’s death and to Commissioner Gordon’s wife Sarah were treated as canonical for a while, even though it was obvious DKR could not belong to then-current continuity (if nothing else because of the collapse of the Soviet Union). And of course there’s Jim Starlin’s and Bernie Wrightson’s The Cult – to quote the always quotable Joe McCulloch, if ‘Frank Miller’s book is the big tough dog with the bowler hat in the Looney Tunes, [The Cult] is the jumpy little dog that races around and does nothing but tell it how completely fucking awesome it is.’

And yet, dated as the book is, it’s not just respect and nostalgia keeping it alive, the truth is that DKR has not completely lost its edge. Foreshadowing, callbacks, overlapping conversations, and multiple intertwined narrative strands give the story a sense of grand scale. Plus it’s full of energy and unrelenting escalation, from the initial summer heat wave to the final near-WWIII nuclear winter. Batman goes up against Two-Face in the first chapter, a mutant gang in the second, Joker in the third, and finally Superman himself in the apocalyptic climax!

That’s right, a mutant gang. The whole thing is packed with grotesque imagery while tapping straight into the eighties’ Zeitgeist of out-of-control violent crime, Reaganomics, and New Age psychobabble (Arkham Asylum is now Arkham Home for the Emotionally Troubled). It’s like a Batman-shaped Jello Biafra song, as Miller throws around the kind of absurdly dark humor he would later bring to the script of Robocop 2.

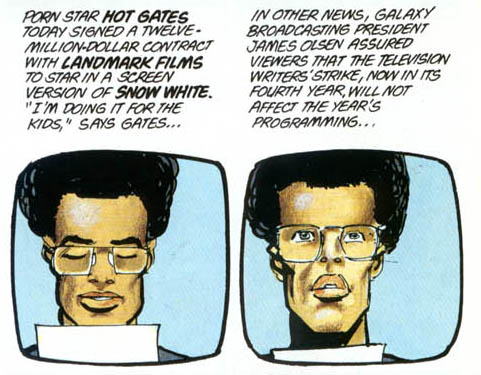

All of this is enhanced a thousand-fold by Frank Miller’s pencils, Klaus Janson’s inks, Lynn Varley’s colors, and John Costanza’s letters. So much of that sense of grand scale I was talking about comes from information-heavy pages, often crammed with as many as 16 panels at once, including loads of talking heads on TV screens… and not only do Miller and his crew pull this off as highly readable, they use it to build up tension before each of the book’s unforgettable splash pages. Take, for example, the way Batman’s return is gradually revealed while keeping him mostly off-panel:

It’s these pages upon pages of shadowy hints and claustrophobic panel grids that lend such pathos to the Dark Knight’s inevitable full-page entrance:

It’s these pages upon pages of shadowy hints and claustrophobic panel grids that lend such pathos to the Dark Knight’s inevitable full-page entrance:

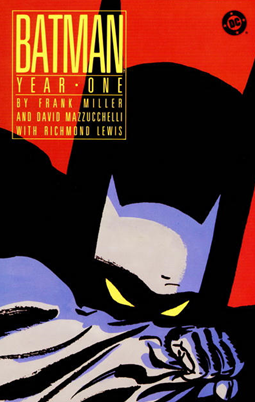

You’d think DKR would be impossible to top. However, according to the latest poll at Comics Should Be Good, Frank Miller’s follow-up project may be even more beloved. In 1987’s Batman: Year One, Miller – this time with David Mazzucchelli on art duties – told the beginning of the Dark Knight’s career, effectively setting up much of the tone and continuity Batman comics would follow for the next two and a half decades.

You’d think DKR would be impossible to top. However, according to the latest poll at Comics Should Be Good, Frank Miller’s follow-up project may be even more beloved. In 1987’s Batman: Year One, Miller – this time with David Mazzucchelli on art duties – told the beginning of the Dark Knight’s career, effectively setting up much of the tone and continuity Batman comics would follow for the next two and a half decades.

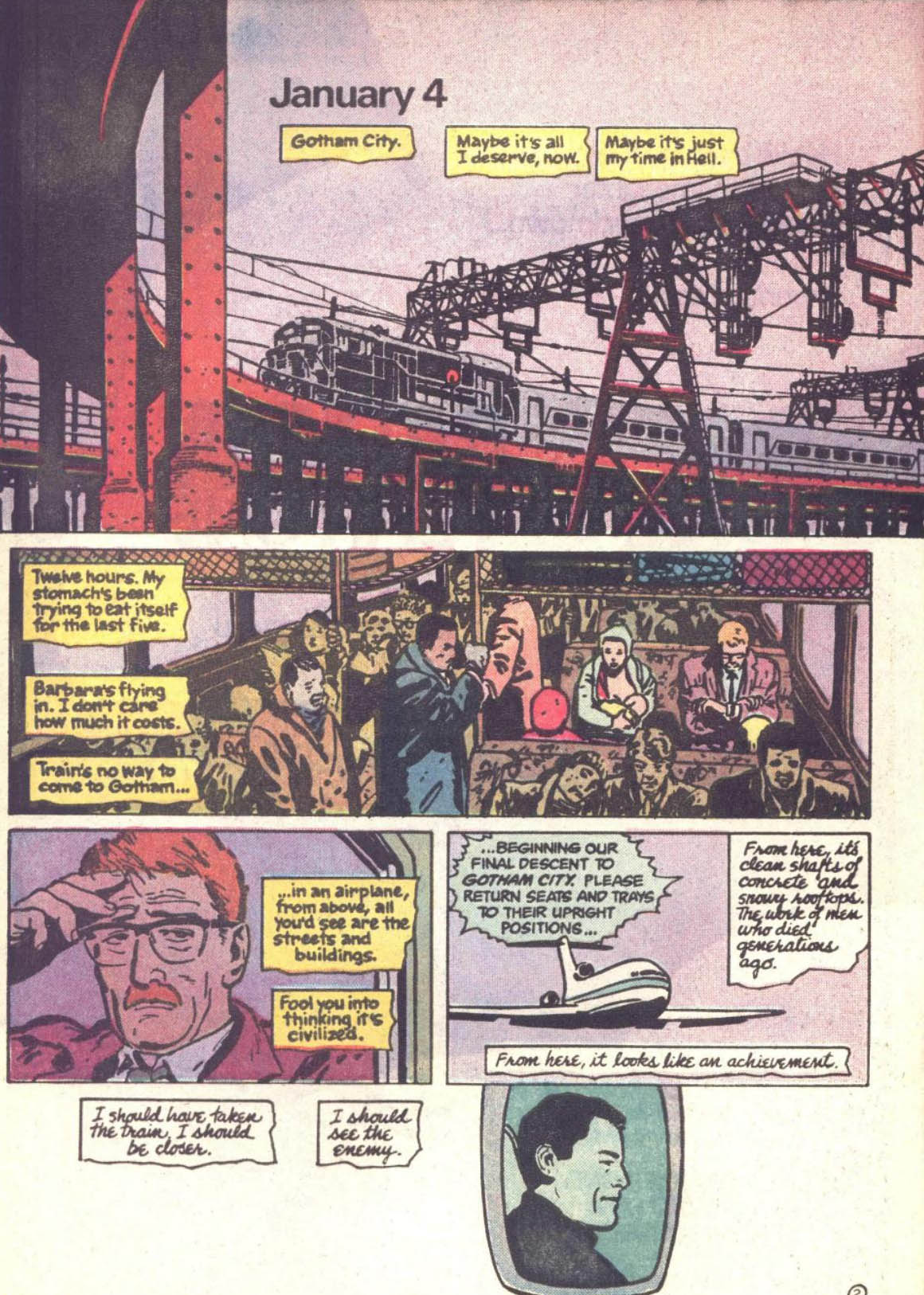

Starting with a young Bruce Wayne’s return to Gotham after having trained around the world, the book covers the roughly one-year period in which Bruce develops his Batman identity, giving us a glimpse of his learning curve as he first tackles the city’s organized crime and rampant corruption. Composed mostly of short vignettes intercut with a few long sequences, Year One is more character study than conventional plot. In an inspired decision, we don’t just get to follow Batman’s growth, but that of Lieutenant James Gordon, who is almost as much a main character as Bruce. Both are fighting for (and against) the city, but one from outside the law and the other from within, one from a position of privilege and the other under constant threat – until they finally join forces when they realize they can hardly trust anyone but each other… It’s a fascinating parallel, and one that is made clear from the opening page:

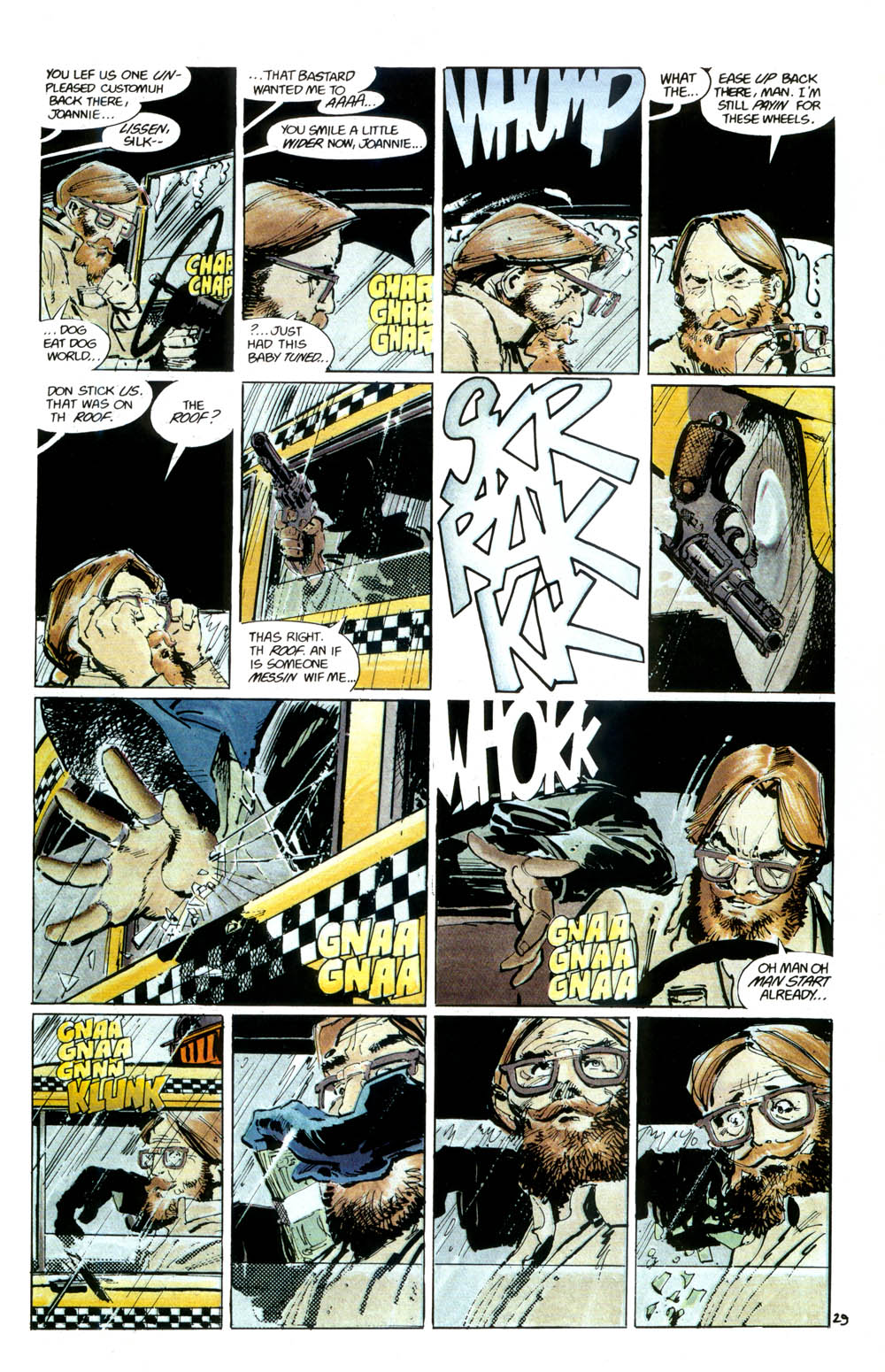

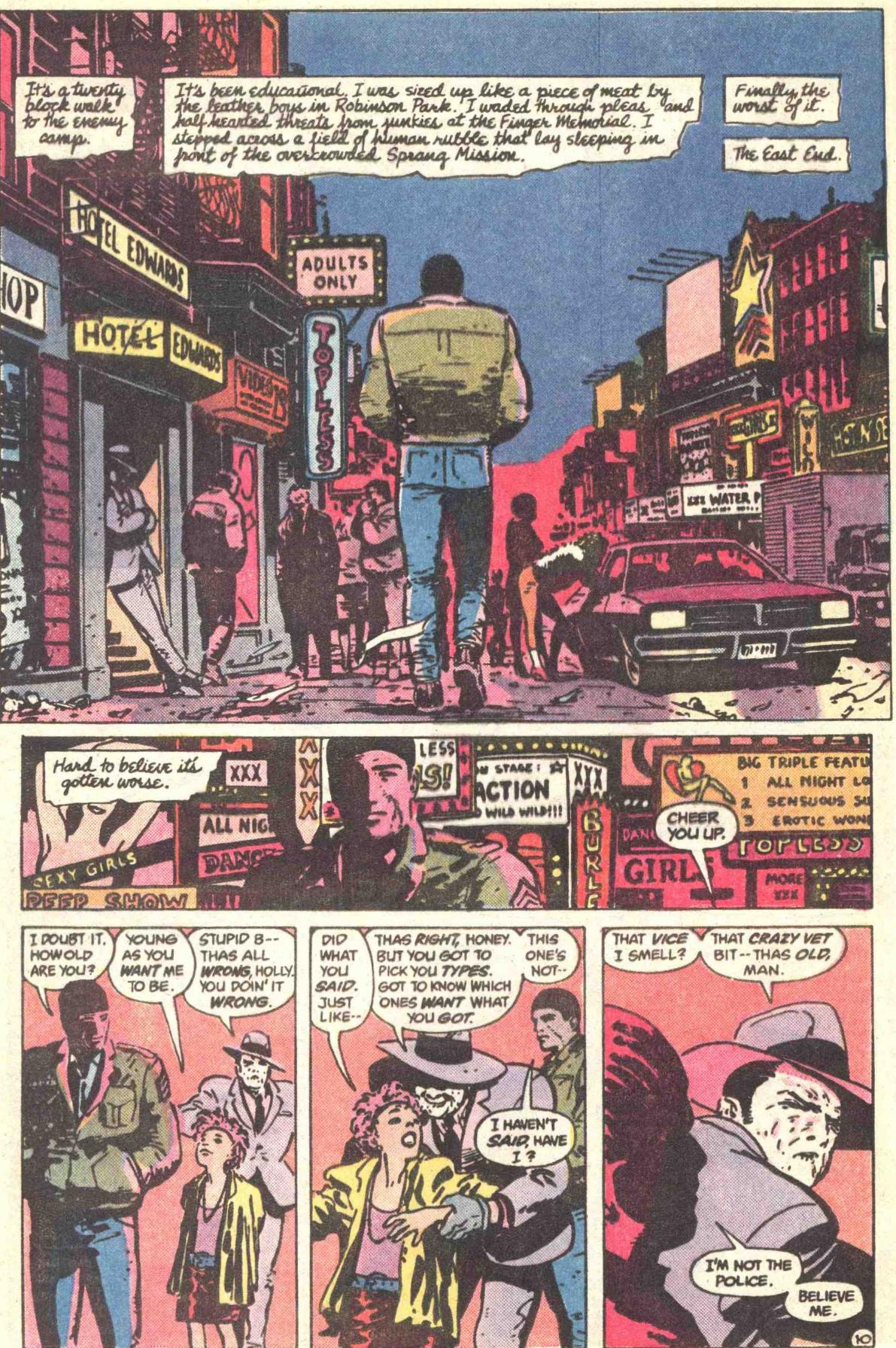

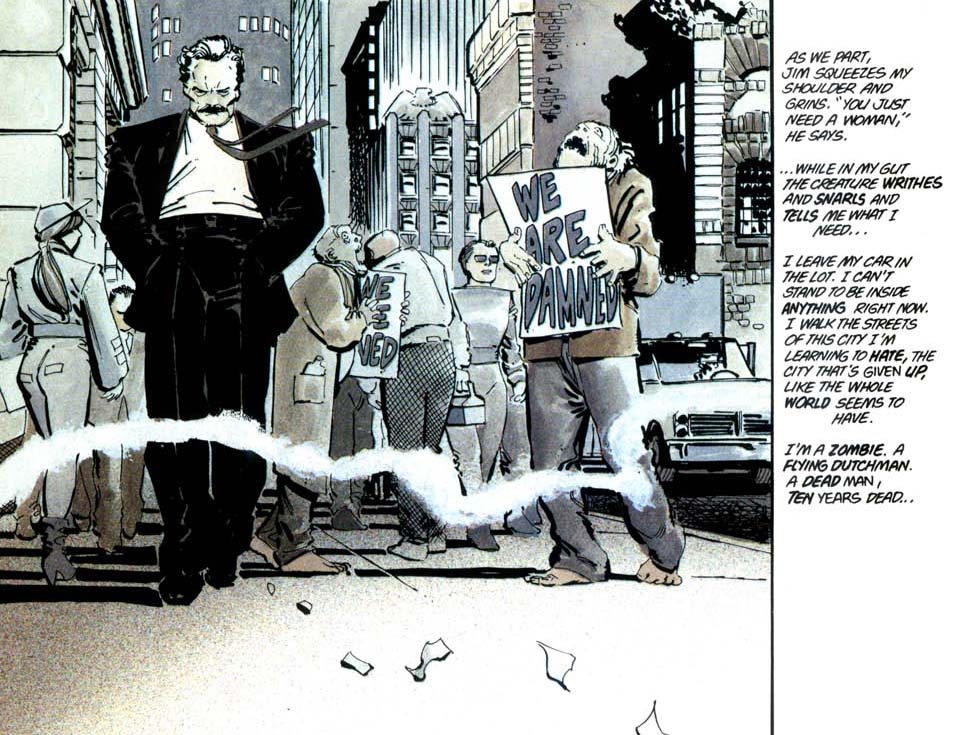

The atmosphere is markedly different from DKR, not least because of Mazzucchelli’s grounded artwork (with moody colors by Richmond Lewis). This is by far the most realistic take on Batman, certainly more than the Christopher Nolan movies, which it heavily inspired. Year One reads like a hardboiled crime story that could make Dashiell Hammett proud, albeit one where a central character sometimes wears a mask with pointy ears. Gotham City is as seedy as it gets – I dare you to spot all the Taxi Driver riffs on this page:

The atmosphere is markedly different from DKR, not least because of Mazzucchelli’s grounded artwork (with moody colors by Richmond Lewis). This is by far the most realistic take on Batman, certainly more than the Christopher Nolan movies, which it heavily inspired. Year One reads like a hardboiled crime story that could make Dashiell Hammett proud, albeit one where a central character sometimes wears a mask with pointy ears. Gotham City is as seedy as it gets – I dare you to spot all the Taxi Driver riffs on this page:

That’s Bruce Wayne disguised as a veteran in his first crime-fighting outing, about to get his butt handed to him… his massive screw-up in this sequence leads to Year One’s most seminal scene:

That’s Bruce Wayne disguised as a veteran in his first crime-fighting outing, about to get his butt handed to him… his massive screw-up in this sequence leads to Year One’s most seminal scene:

In a direct echo of DKR, the bat that inspires Bruce doesn’t merely fly through an open window, like in Batman’s classic origin…

In a direct echo of DKR, the bat that inspires Bruce doesn’t merely fly through an open window, like in Batman’s classic origin…

This is the end of the first chapter (originally published as the issue Batman #404) – in the following three, things get even more intense, as Batman and Gordon are continuously put to the test, physically and psychologically. In the end, they carve out a small niche of honesty in Gotham City, but there’s clearly still a lot to be done.

This is the end of the first chapter (originally published as the issue Batman #404) – in the following three, things get even more intense, as Batman and Gordon are continuously put to the test, physically and psychologically. In the end, they carve out a small niche of honesty in Gotham City, but there’s clearly still a lot to be done.

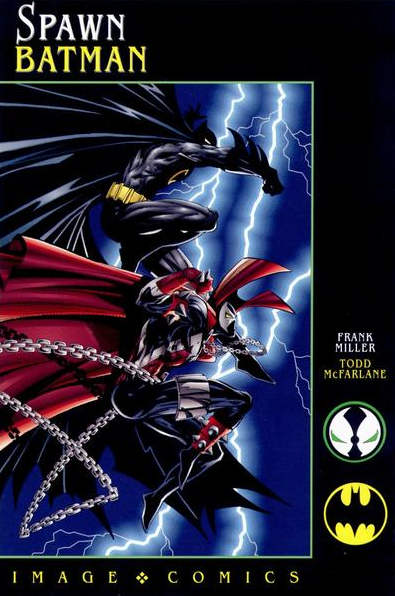

Having left his indelible mark on the Dark Knight, Frank Miller moved on to other projects. It took until 1994 for him to first revisit the character, with the Spawn/Batman one-shot:

In this intercompany crossover drawn by Todd McFarlane, Batman grudgingly teams up with Image Comics’ homeless, amnesiac, demonic anti-hero Spawn. There is some mindless plot involving cyborgs with decapitated human heads, but the comic’s mostly just Batman and Spawn being jerks to each other, leading up to a fun punchline. Although the cover shamelessly tries to make it look like a follow-up to DKR, the breadth and gravitas of the former are completely lacking. It would be another 7 years before a proper sequel showed up:

In this intercompany crossover drawn by Todd McFarlane, Batman grudgingly teams up with Image Comics’ homeless, amnesiac, demonic anti-hero Spawn. There is some mindless plot involving cyborgs with decapitated human heads, but the comic’s mostly just Batman and Spawn being jerks to each other, leading up to a fun punchline. Although the cover shamelessly tries to make it look like a follow-up to DKR, the breadth and gravitas of the former are completely lacking. It would be another 7 years before a proper sequel showed up:

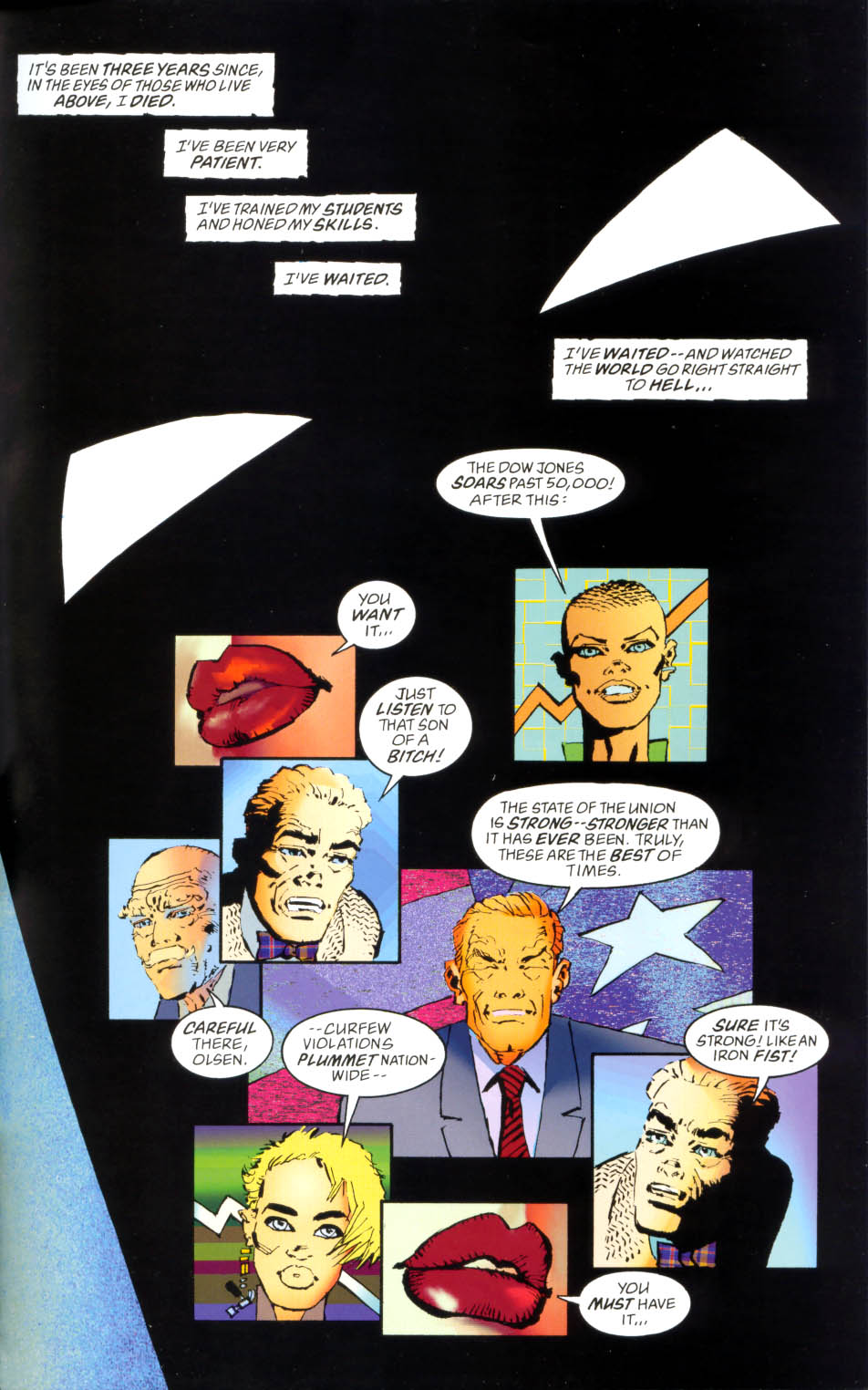

If The Dark Knight Returns was a manifestation of 1980s’ Cold War cyberpunk nihilism, The Dark Knight Strikes Again channeled late 1990s’ hyper-sexualized satirical exuberance. To put it in Carpenter terms, if DKR was Escape from New York, then DKSA was Escape from LA. On top of the newscasts (from many diverse, thematic channels, including bizarre anchors such as naked women, manga cartoons, and Alfred E. Neuman), now we got bombarded with misogynistic adverts, a ‘superhero chic’ fashion trend, a computer-generated President of the United States, and an overload of swearing and pop culture Easter eggs.

If The Dark Knight Returns was a manifestation of 1980s’ Cold War cyberpunk nihilism, The Dark Knight Strikes Again channeled late 1990s’ hyper-sexualized satirical exuberance. To put it in Carpenter terms, if DKR was Escape from New York, then DKSA was Escape from LA. On top of the newscasts (from many diverse, thematic channels, including bizarre anchors such as naked women, manga cartoons, and Alfred E. Neuman), now we got bombarded with misogynistic adverts, a ‘superhero chic’ fashion trend, a computer-generated President of the United States, and an overload of swearing and pop culture Easter eggs.

DKSA is kind of a mess, but a glorious one. Once again, threats follow one after the other without letting go: there’s a tyrannical government, an asteroid headed for Earth, rumors of an alien invasion, Lex Luthor, Brainiac, and the return of the Joker – and that’s before the planet somehow gets sucked by a giant energy matrix. Make no mistake, we’re unapologetically in superhero fantasy territory, the book populated by outlandish versions of DC characters such as the Atom, the Question, Green Arrow, Green Lantern, and Plastic Man, not to mention countless cameos. With his tongue firmly lodged in his cheek and apparently burning with revolutionary fervor, Miller throws all sorts of iconoclastic images at the reader, from Wonder Woman and Superman having sex in space to Batman beating up the Secretary of State and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

DKSA is kind of a mess, but a glorious one. Once again, threats follow one after the other without letting go: there’s a tyrannical government, an asteroid headed for Earth, rumors of an alien invasion, Lex Luthor, Brainiac, and the return of the Joker – and that’s before the planet somehow gets sucked by a giant energy matrix. Make no mistake, we’re unapologetically in superhero fantasy territory, the book populated by outlandish versions of DC characters such as the Atom, the Question, Green Arrow, Green Lantern, and Plastic Man, not to mention countless cameos. With his tongue firmly lodged in his cheek and apparently burning with revolutionary fervor, Miller throws all sorts of iconoclastic images at the reader, from Wonder Woman and Superman having sex in space to Batman beating up the Secretary of State and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

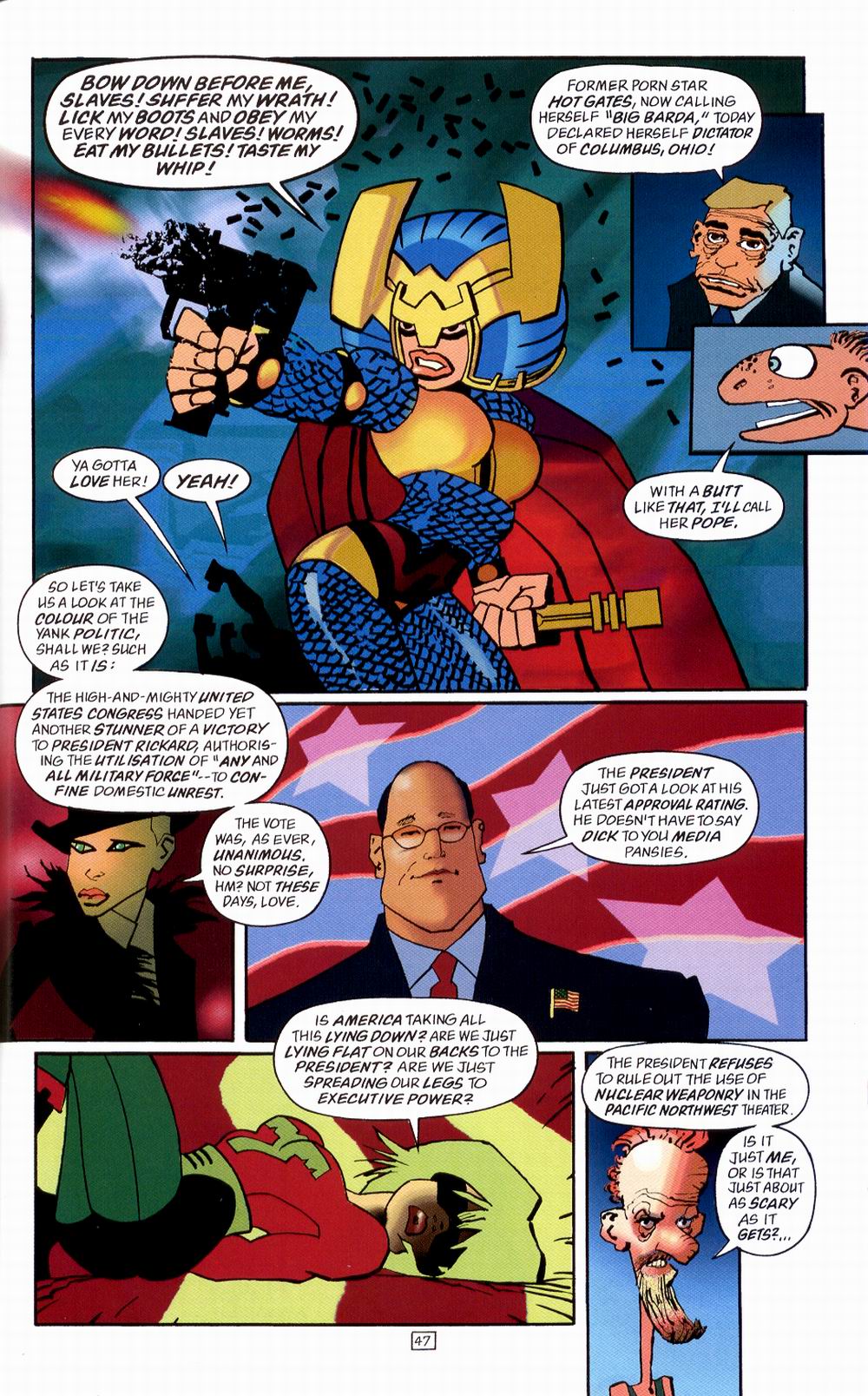

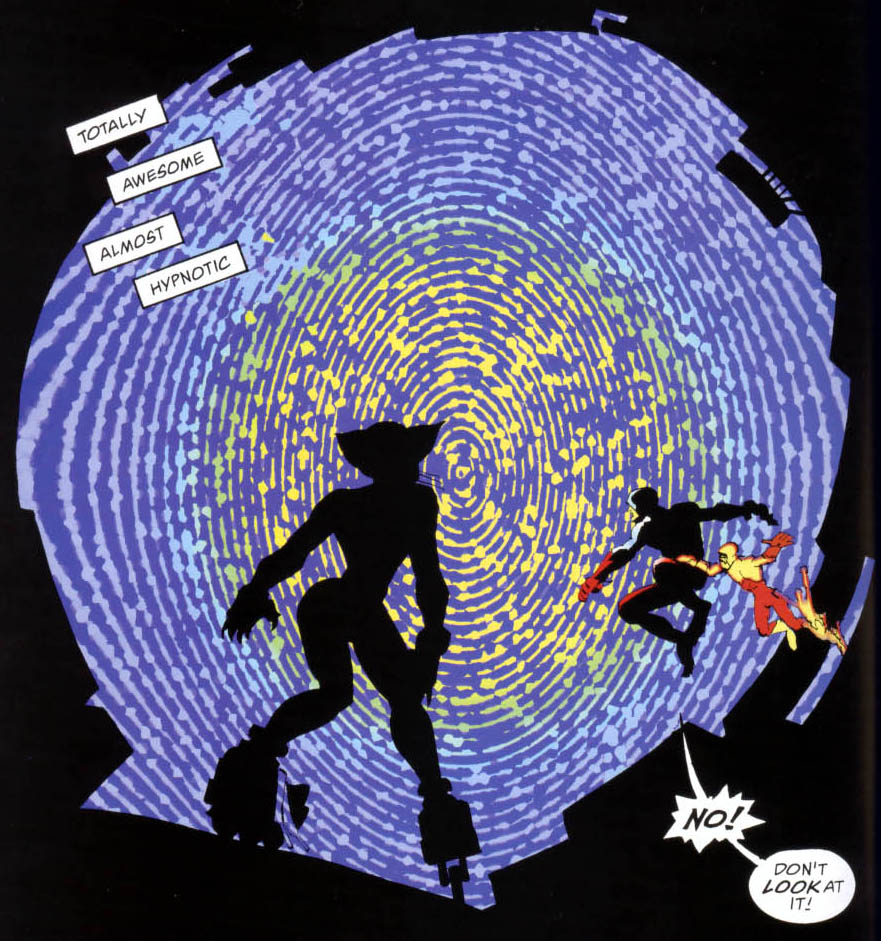

Frank Miller’s art keeps up with the new attitude, delivering psychedelic layouts and bow-before-me double-page spreads. Like in DKR, Miller slowly builds up the Dark Knight’s entrance, this time waiting until the end of the first chapter, almost 80 pages into the book, before he lets us gaze at Batman’s ugly mug (everyone is ugly in this comic, which suits it just fine). Art-wise, though, it’s as much Lynn Varley’s show as it is Miller’s. The book looks like a blinding neon-light. Varley saturates it with bright colors, pixilates strategic bits, and creates dazzling effects as in the sequence where Batman’s army releases the Flash (who for years had been kept running in a wheel to provide electricity for a third of the country).

Frank Miller’s art keeps up with the new attitude, delivering psychedelic layouts and bow-before-me double-page spreads. Like in DKR, Miller slowly builds up the Dark Knight’s entrance, this time waiting until the end of the first chapter, almost 80 pages into the book, before he lets us gaze at Batman’s ugly mug (everyone is ugly in this comic, which suits it just fine). Art-wise, though, it’s as much Lynn Varley’s show as it is Miller’s. The book looks like a blinding neon-light. Varley saturates it with bright colors, pixilates strategic bits, and creates dazzling effects as in the sequence where Batman’s army releases the Flash (who for years had been kept running in a wheel to provide electricity for a third of the country).

While many panned DKSA, it still has a significant cult following. The same can’t be said for Frank Miller’s next big Batman project – and no, I’m not referring to the movie screenplay where Miller interestingly reinvented Bruce Wayne as an underprivileged vigilante who lives in the ghetto and gets called Batman because his signet ring leaves a bat-shaped mark when he punches criminals.

While many panned DKSA, it still has a significant cult following. The same can’t be said for Frank Miller’s next big Batman project – and no, I’m not referring to the movie screenplay where Miller interestingly reinvented Bruce Wayne as an underprivileged vigilante who lives in the ghetto and gets called Batman because his signet ring leaves a bat-shaped mark when he punches criminals.

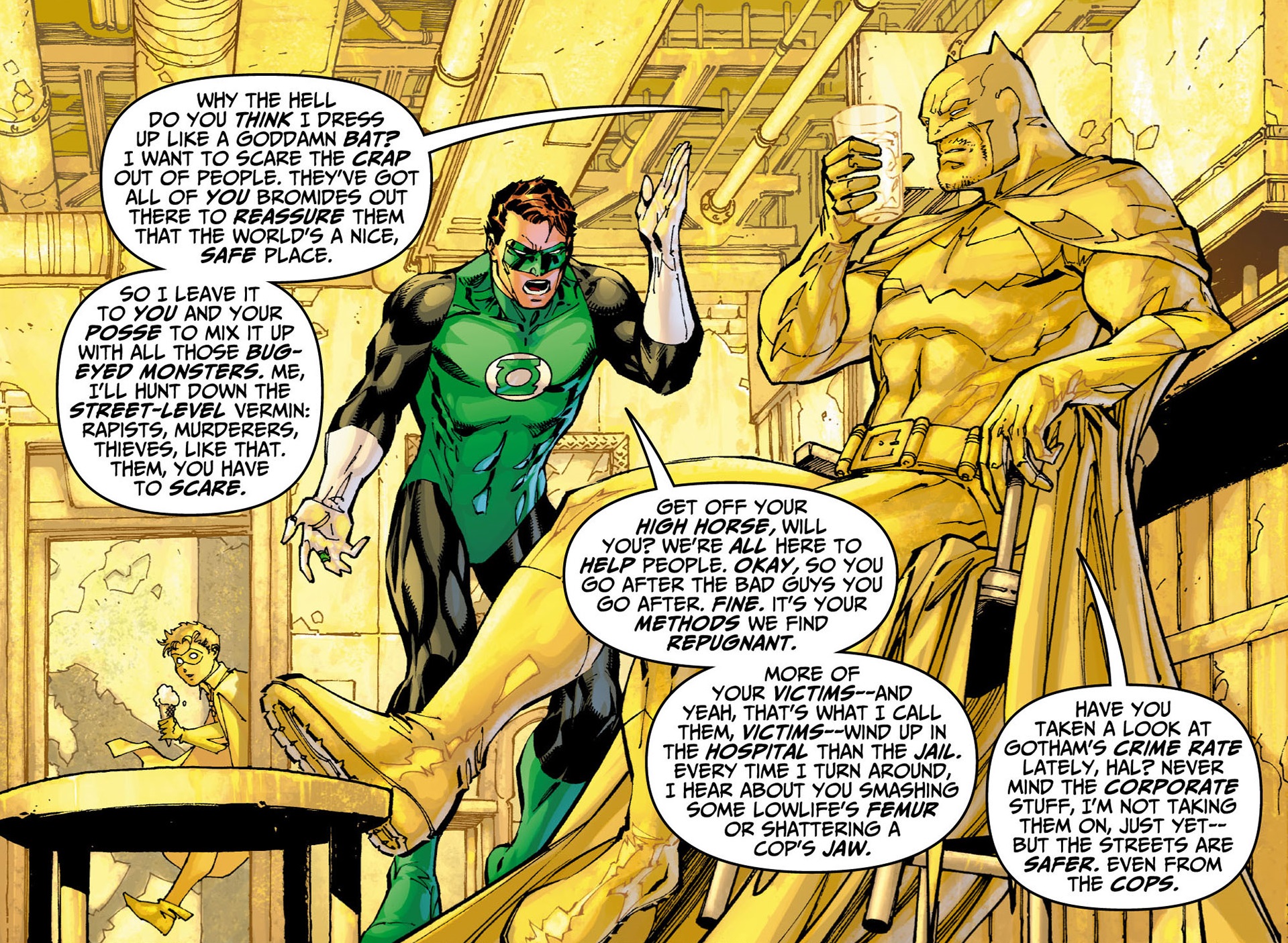

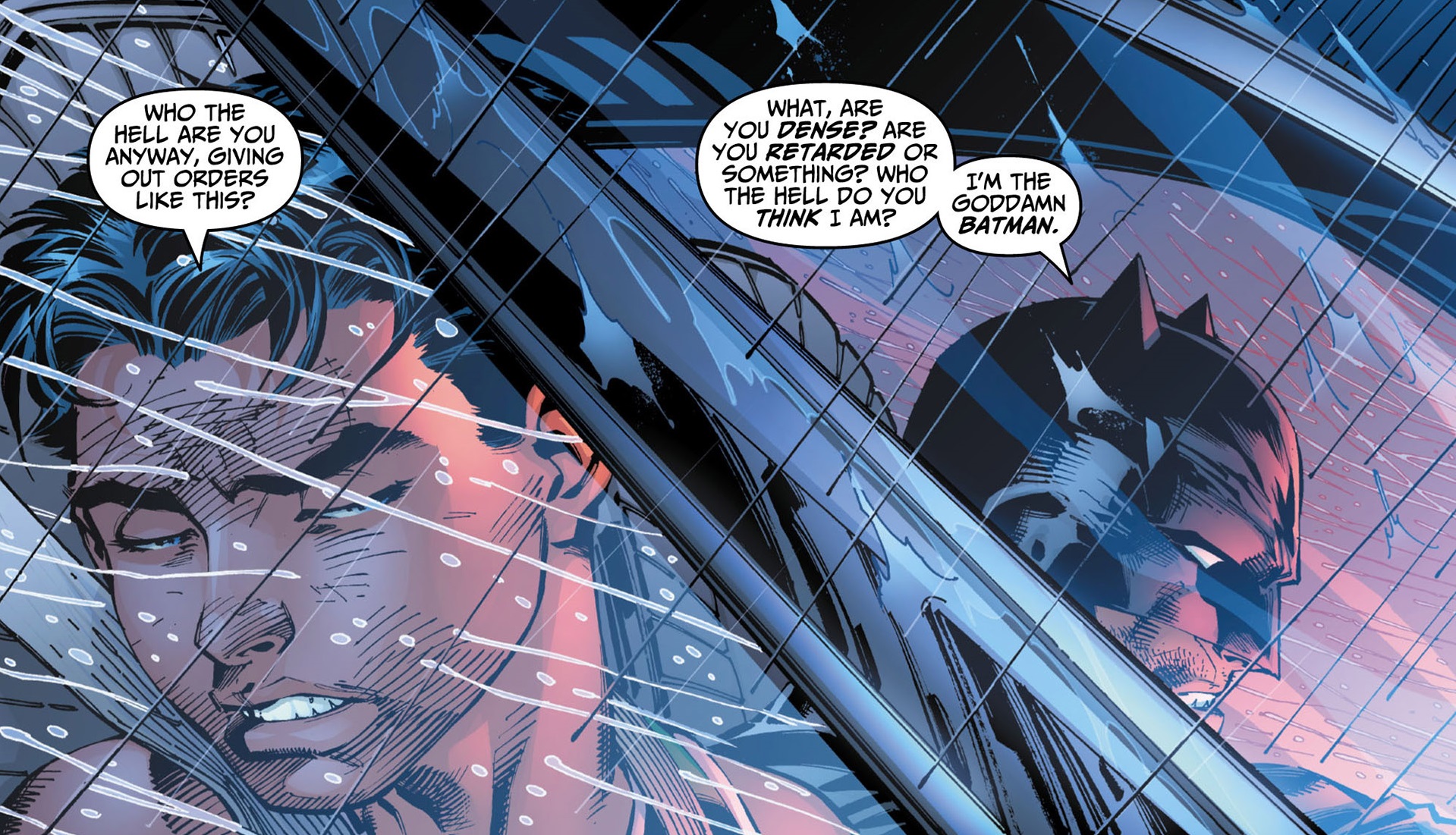

All Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder tells the story of how the Dark Knight first took Robin (Dick Grayson) under his wing. This Batman is an unlikable douchebag, a fully-formed egomaniac, and a sadist. His version of tough love consists of leaving Dick – hours after the kid’s parents were murdered – to sleep on the Batcave’s floor, encouraging him to hunt and eat rats to survive… Among all the physical and verbal abuse, Batman delivers what instantly became the comic’s most infamous passage:

In what I assume is Frank Miller’s idea of a provocation, the expression ‘goddamn Batman’ keeps coming up, as if to encourage a drinking game… Like the Dark Knight, the other characters in All Star (there are many, as Miller keeps enlarging the cast without doing anything interesting with them) are all assholes, including a hyperbolically man-hating Wonder Woman that sounds like an anti-feminist caricature. The only redeeming approach to this comic is to take it as a mean-spirited joke at DC’s expense (think Garth Ennis, on a bad day) – there’s no way the scene where Batman paints himself yellow to face Green Lantern (whose powers don’t work on yellow things) is not being played for laughs on some level, despite the stern dialogue:

It’s not just the dialogue that’s terrible – the endless internal monologues, with their awful badass-wannabe staccatos, seem to come out of abandoned first drafts for Frank Miller’s much cooler, film noir-pastiche series, Sin City.

It’s not just the dialogue that’s terrible – the endless internal monologues, with their awful badass-wannabe staccatos, seem to come out of abandoned first drafts for Frank Miller’s much cooler, film noir-pastiche series, Sin City.

As for the art, by Jim Lee (pencils), Scott Williams (inks), and Alex Sinclair (colors), there is a lot to be admired here, but it is too conventional to express Miller’s eccentricities. The comic is full of boring superhero poses and objectified women (Sin City also fetishizes female bodies, of course, but at least there Miller’s use of negative space and high-contrast black & white creates a distinctly atmospheric visual style, while All Star is straight-up cheesecake of the blandest brand).

And finally there is 2011’s Holy Terror. This started as Frank Miller’s pet project about Batman fighting Osama Bin Laden, an overtly propagandistic tale in line with those World War II comics where mainstream superheroes punched Hitler in the chin. After DC dropped the project, Miller ended up doing a graphic novel featuring an obvious ersatz-Batman called the Fixer (as well as thinly veiled versions of Gotham City, Catwoman, and Commissioner Gordon).

Holy Terror was widely bashed with (deserved) accusations of Islamophobia, reinforced by Frank Miller’s chauvinistic interviews at the time. Not even Miller’s impressive, expressionistic art renders the comic less painfully unreadable. I guess I could live with the tastelessness of a superhero story about Al-Qaeda or with the discomfort over the book’s war-mongering politics were it not for its crude bigotry and no-nonsense, irony-free delivery:

Holy Terror was widely bashed with (deserved) accusations of Islamophobia, reinforced by Frank Miller’s chauvinistic interviews at the time. Not even Miller’s impressive, expressionistic art renders the comic less painfully unreadable. I guess I could live with the tastelessness of a superhero story about Al-Qaeda or with the discomfort over the book’s war-mongering politics were it not for its crude bigotry and no-nonsense, irony-free delivery:

So what went wrong? How did the most respected Batman author of the eighties turn into such an inept, maligned creator? There are two tempting answers.

So what went wrong? How did the most respected Batman author of the eighties turn into such an inept, maligned creator? There are two tempting answers.

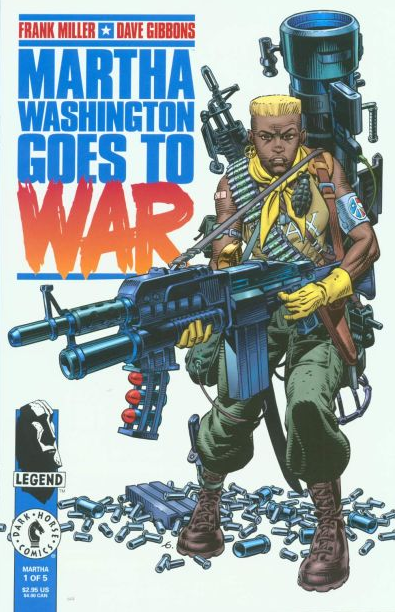

One is to regard Frank Miller’s Batman work as part of a broader creative decline throughout his career. In the ’80s, everything Miller touched turned to gold, such as his two celebrated runs on Daredevil and respective spinoffs – especially the insane masterpiece that is Elektra: Assassin. His ’90s portfolio, although less ambitious than in the previous decade, includes plenty of strong work: Hard Boiled, The Man Without Fear, Sin City, even 300 is not too bad. In the 21st century, though, Frank Miller’s voice has become a parody of macho posturing and faux-noir tropes. The laughably bad movie The Spirit (written and directed by Miller) seems like an Airplane-style spoof of Sin City. You can blame this trajectory on Miller running out of steam or go into more personal territory and read it as a result of his devotion to Objectivism, which took away the postmodern ambiguity of his early work. Regardless, no series illustrates this (d)evolution better than Martha Washington: the original 1990 mini-series was a very cool futuristic satire, which was followed by a bunch of solid-yet-dispensable sequels with gradually diminishing returns until a pompous, jingoistic finale in 2007’s Martha Washington Dies one-shot.

Another interpretation is that Frank Miller’s voice hasn’t changed that much, but Batman comics have (to a great degree, precisely because of Miller’s original impact). Writing the Dark Knight as a quasi-Charles Bronson loose-cannon vigilante in a violent and sleazy world was relatively shocking, innovative, and thought-provoking in the mid-1980s, but certainly no longer in the 2000s, where such a depiction has become the norm. Miller’s recent work is just another drop in the ocean of comics featuring an arrogant, lunatic Batman, albeit a particularly unpleasant one to read. His latest stuff does seem to be trying to outdo the competition by raising the level of cruelty, but perhaps the most rewarding way to approach it is to regard it as a commentary on the state of the art – by presenting Batman as an unsympathetic Dark Knight-on-steroids, these comics can serve to either denounce the dangers of this power fantasy if taken to a logical extreme or to refreshingly mock its self-importance. Either way, I’m not sure Frank Miller has been informed…

Another interpretation is that Frank Miller’s voice hasn’t changed that much, but Batman comics have (to a great degree, precisely because of Miller’s original impact). Writing the Dark Knight as a quasi-Charles Bronson loose-cannon vigilante in a violent and sleazy world was relatively shocking, innovative, and thought-provoking in the mid-1980s, but certainly no longer in the 2000s, where such a depiction has become the norm. Miller’s recent work is just another drop in the ocean of comics featuring an arrogant, lunatic Batman, albeit a particularly unpleasant one to read. His latest stuff does seem to be trying to outdo the competition by raising the level of cruelty, but perhaps the most rewarding way to approach it is to regard it as a commentary on the state of the art – by presenting Batman as an unsympathetic Dark Knight-on-steroids, these comics can serve to either denounce the dangers of this power fantasy if taken to a logical extreme or to refreshingly mock its self-importance. Either way, I’m not sure Frank Miller has been informed…

One day I’ll make myself read all of Miller’s non-Batman work to have a proper frame of reference for the sheer lunacy of All-Star (and by extension Holy Terror). That day is not today.

Anyways, in terms of story I’ve long favored Year One, but in structure I’ve always found DKR more compelling. The 4X4 grid makes it almost like reading a big book of Doonesbury strips, which perhaps makes all the political soapboxing less obnoxious that it’d be otherwise…

Found this post by chance, searching for a picture of the last page of Year One chater 1 (the bat entrance through the glass), as reference for a colleague.

What a great reading! Not only that, I also feel less alone in finding the [mis]adventures of Mr. Frank Miller depressing. He was my favourite artist at the time, and slowly creeped into a bad vaersion of his own page filling head-characters.

Thank you for a great writeup!