The 1970s were a great time for the Caped Crusader, even if, looking back, we did miss out on the chance to see Batman with a turtleneck or Catwoman with an afro (problem solved). After the kitsch of the ’60s and before the grit of the ’80s, creators seemed to have found a firm balance between a Batman that was dark enough to be cool without yet being an ultraviolent psychopath. The outlook was perfectly captured by artists like Neal Adams, Bob Brown, Irv Novick, and Jim Aparo, who gave the character realistic proportions and a gothic cape and cowl. In terms of writing, Denny O’Neil and Frank Robbins deserve a lot of credit for this tonal shift. A few weeks ago, I spotlighted O’Neil, still fondly remembered as one of the greatest Batman writers of all time. History has been less kind to Frank Robbins.

There are several reasons for this. For one thing, although Robbins would go on to write some truly solid stuff in the 1970s, he didn’t start off that way. In 1968, when he replaced Gardner Fox in Batman and Detective Comics, Robbins didn’t immediately move away from the camp of the TV show (which had just been cancelled), particularly regarding the incessant wordplay… Seriously, in Batman #205, an unrelenting kick-ass action issue if there ever was one, I counted 25 playful puns and 14 amusing alliterations (personal favorite: referring to Batman as ‘fearless ferret’).

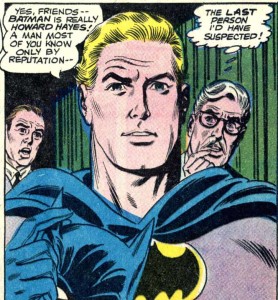

While Novick and Brown gave the stories a hard-edged look from the onset, some of Frank Robbins’ earlier scripts are firmly tongue-in-cheek, including some gloriously goofy romans à clef. In ‘Batman’s Big Blow-Off!’ a beatnik newspaper pushes the Caped Crusader into revealing his secret identity, so he convinces an obvious Howard Hughes stand-in to be used as a front.

Batman #211

Batman #211

Things get even more out of control when the ersatz-Howard Hughes gets jealous of Batman’s popularity, undergoes intensive martial arts training, and damn near kills the Dark Knight in order to take his place!

If you think this is out there, it probably means you haven’t read ‘Dead… Till Proven Alive!’ where Batman and Robin investigate the urban legend that Paul McCartney died in 1966 and was secretly replaced by a lookalike… At one point, the Dynamic Duo tries to find out the truth by getting the Beatles to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to Alfred and then comparing voice-recordings.

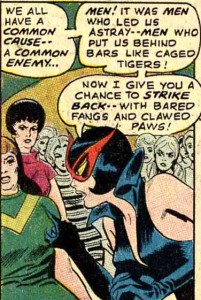

Frank Robbins was certainly fond of incorporating contemporary references in his work – a zanier version of Law & Order’s ‘ripped from the headlines’ – yet the Zeitgeist did not always manifest itself in the ways you’d expect. Take the women’s rights movement. In ‘The Case of the Purr-Loined Pearl,’ Catwoman recruits female ex-cons into her gang with the promise of getting revenge against the men in their lives…

Batman #210

Batman #210

The result, however, is that Catwoman forces her new partners to undergo an intensive workout and sauna program in order to be slim enough to fit into a tight, sexy costume, just like hers, so that they can serve as distraction while she steals a shiny pearl!

And then there is ‘Batman’s Marriage Trap!’ where some male crooks come up with the most mesmerizingly misogynous plan ever:

Batman #214

Batman #214

In order to screw up Batman’s nightly activities, the crooks literally spend a million dollars on advertising and create a women’s NGO demanding that the Caped Crusader get married – what the gang leader respectfully refers to as a ‘chick-harassing strategy.’ This leads to Batman being chased by a massive demonstration of female protesters who accuse him of promoting singlehood:

Batman #214

Batman #214

As if kick-starting a whole grassroots movement wasn’t already an overelaborate stratagem, trust me, in the end the crooks’ actual plan manages to make even less sense…

If Denny O’Neil was the hippy-looking liberal writer who at the same time as scripting Batman was also telling social awareness stories with Green Arrow explaining racism to Green Lantern, Frank Robbins – in his mid-fifties by then – seemed genuinely concerned, if not confused, about the values of the flower power generation. In ‘Take-Over of Paradise,’ an activist gang barricades itself on a high-rise to demand low-cost housing. Batman proudly stands up for the ‘establishment,’ grumpily arguing that the protesters are ‘grown men – in a man’s world! And they play the games with civilized rules – or suffer the consequences!’ The story does reflect divergences between well-meaning protesters and those willing to kill to achieve their aims, but in the end the main villain is revealed as a ‘femme lib’ girl, out to take over the gang and show her partners what a female leader could do.

This is just one of many stories pitting Batman – as well as Robin and Batgirl, in Detective Comics’ backup features – against out-of-control members of the younger subculture. However, in ‘Freak-Out at Phantom Hollow,’ Frank Robbins does acknowledge the intolerance faced by long-haired hippies in small town America, unsubtly comparing their plight to the witch hunts of 300 years ago.

Another reason Robbins didn’t reach O’Neil’s status is that his contributions to the Batman mythos were not as enduring…

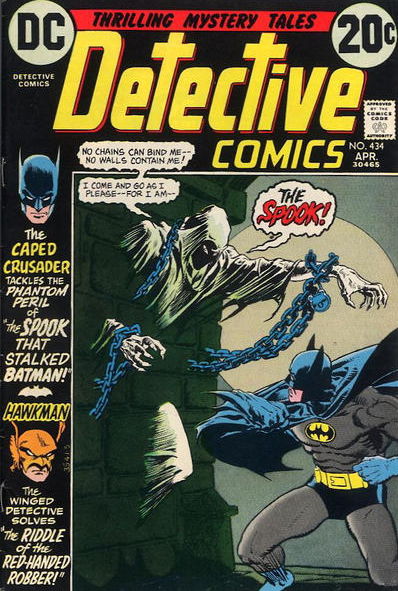

Frank Robbins’ most remarkable recurring villain was the Spook, an escape artist extraordinaire who charged criminals for helping them break out of jail. The Spook made very few appearances post-Robbins – ironically, the ‘Houdini of the Crime-World’ served one of the longest sentences, finally being released on parole in 2003 (in Gotham Knights #46). Pathetically, he later ended up decapitated by Batman’s ten-year-old son.

Frank Robbins’ most remarkable recurring villain was the Spook, an escape artist extraordinaire who charged criminals for helping them break out of jail. The Spook made very few appearances post-Robbins – ironically, the ‘Houdini of the Crime-World’ served one of the longest sentences, finally being released on parole in 2003 (in Gotham Knights #46). Pathetically, he later ended up decapitated by Batman’s ten-year-old son.

As for the Ten-Eyed-Man, a war veteran security guard who mistakenly blames Batman for his blindness, has his optic nerves reconnected into his fingertips so that he can see through his hands, and hijacks an airplane across the world in order to take his revenge on the Caped Crusader in the depths of the Vietnamese jungle – well, for some reason most writers just didn’t know what to do with this character!

Only Man-Bat continues to find a semi-regular presence in the comics, yet he still gets much less exposure than, say, the O’Neil-created Ra’s and Talia al Ghul… This is not surprising, given that the al Ghul clan has the potential for twisted family dramatics around an interesting emotional triangle and stories in which the whole world is at stake, while Man-Bat is essentially just another variation on The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, albeit a visually interesting one:

Detective Comics #400

Detective Comics #400

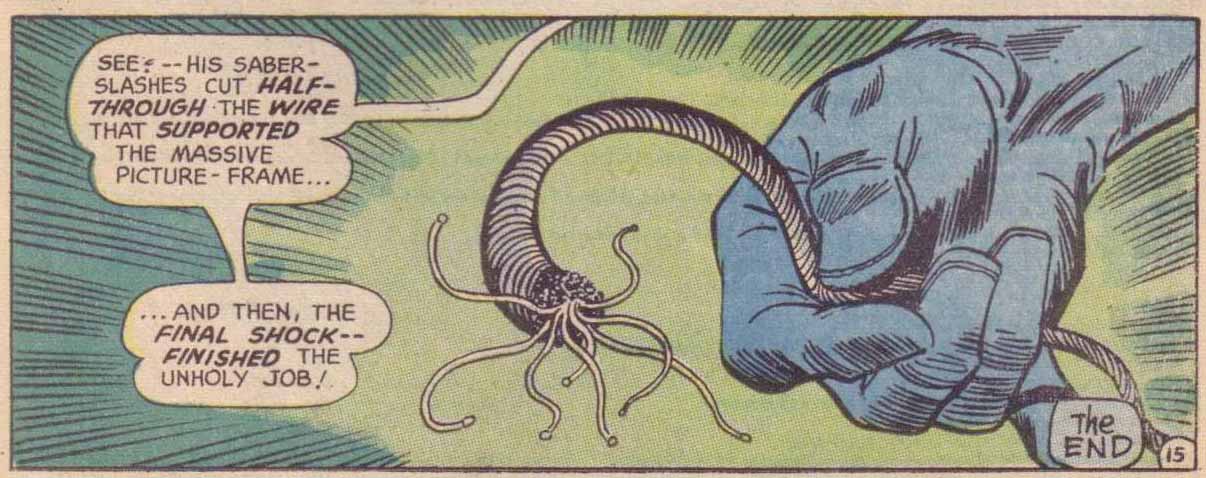

Finally, there’s the fact that Frank Robbins didn’t have Denny O’Neil’s knack to stick the landings. O’Neil usually found a perfect, poetic note to serve as punchline, whether it was Batman writing the year of the villains’ death on their tombstones in ‘The Secret of the Waiting Graves’ or a Holocaust survivor impaling himself next to the Star of David in ‘Night of the Reaper!’ In turn, more often than not Robbins was still explaining his plot twists until the very final panel…

Detective Comics #409

Detective Comics #409

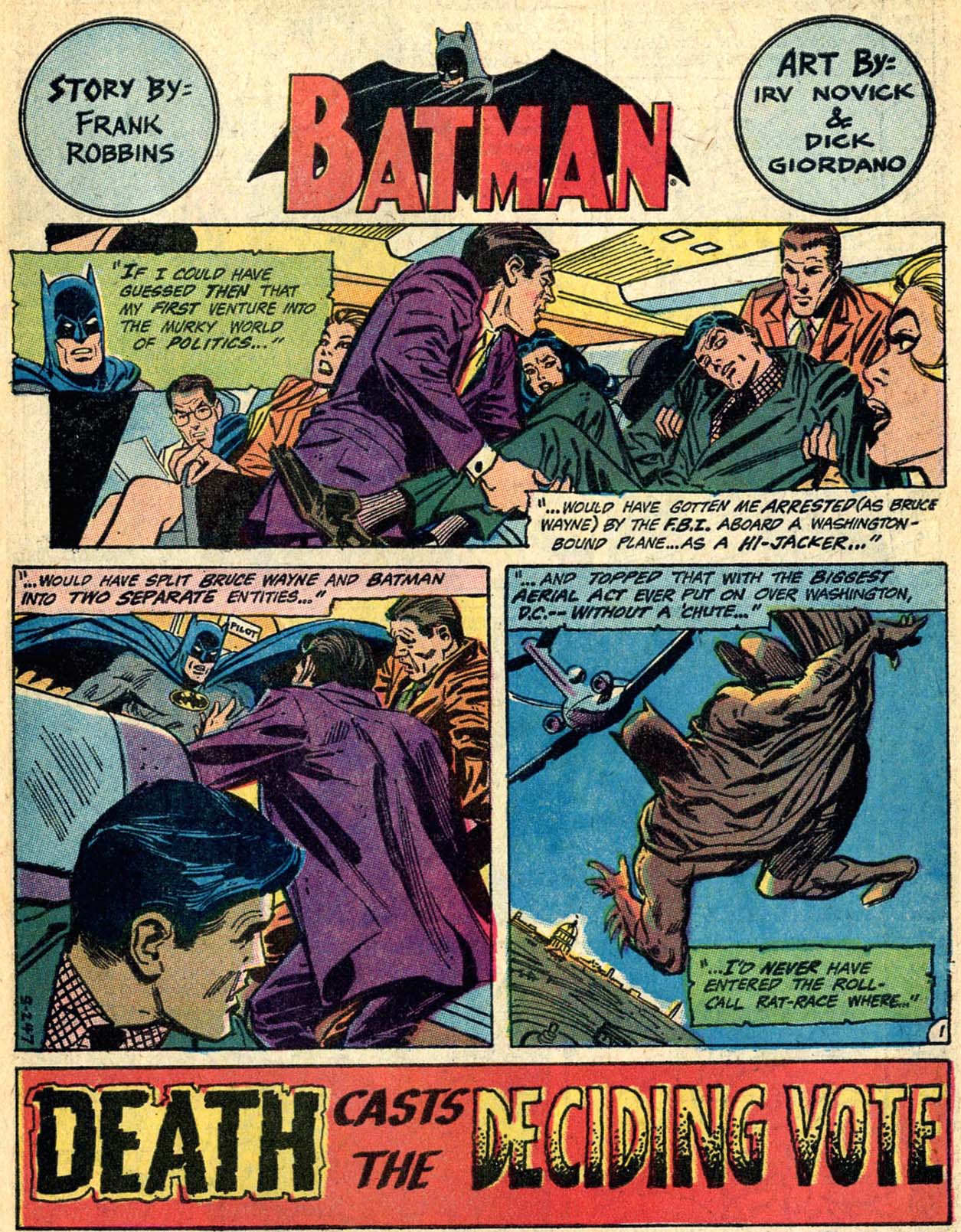

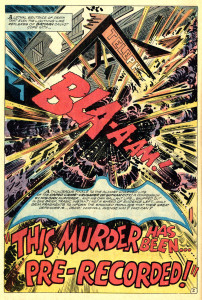

Nevertheless, the truth is that Frank Robbins wrote many fun stories. While he may have sometimes rushed the endings, he did have a skill for slam-bang openings, grabbing the reader from the start:

Batman #219

Batman #219

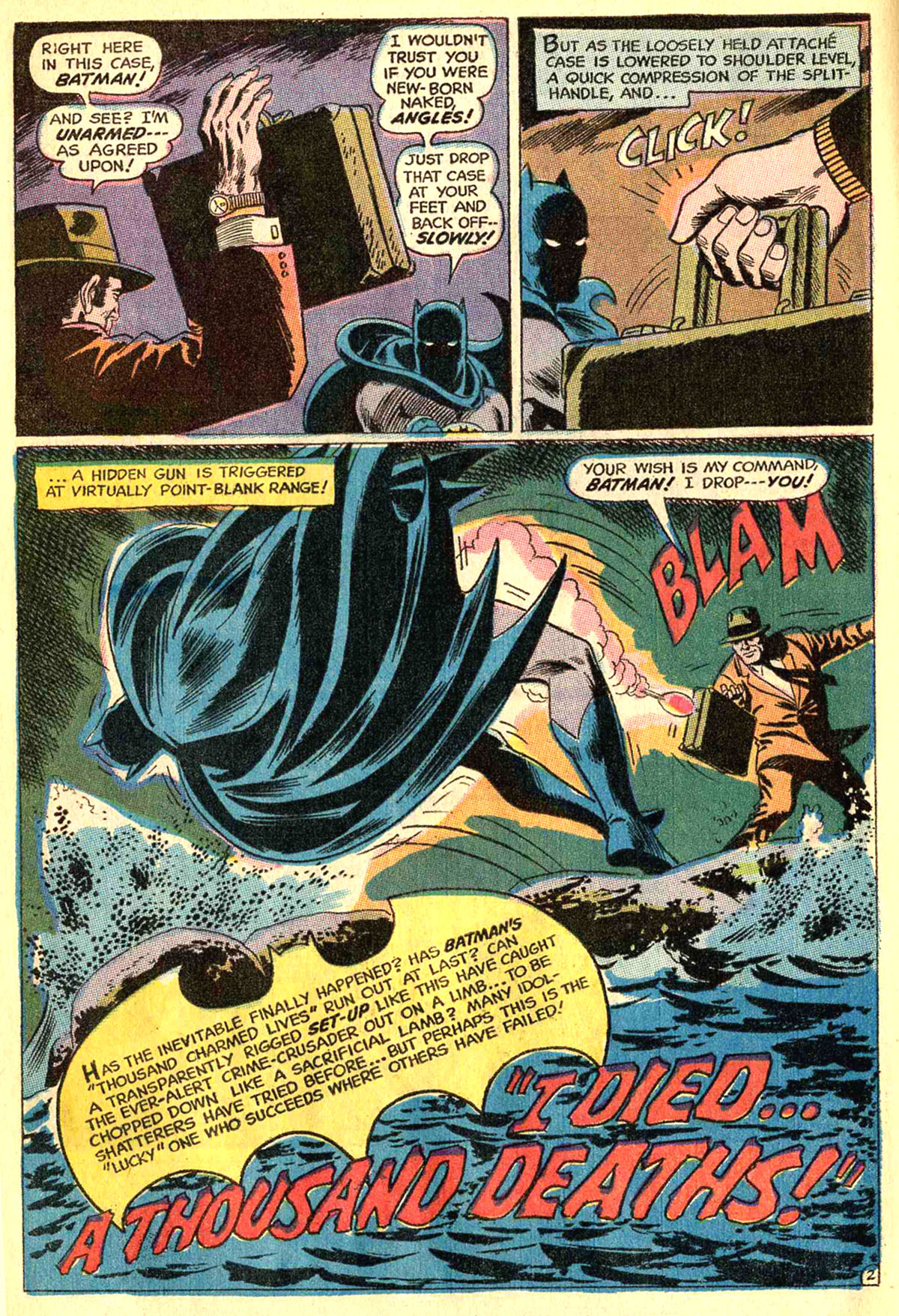

One of his trademarks was to shamelessly appear to kill Batman on the title pages:

Detective Comics #392

Detective Comics #392

Batman #204

Batman #220

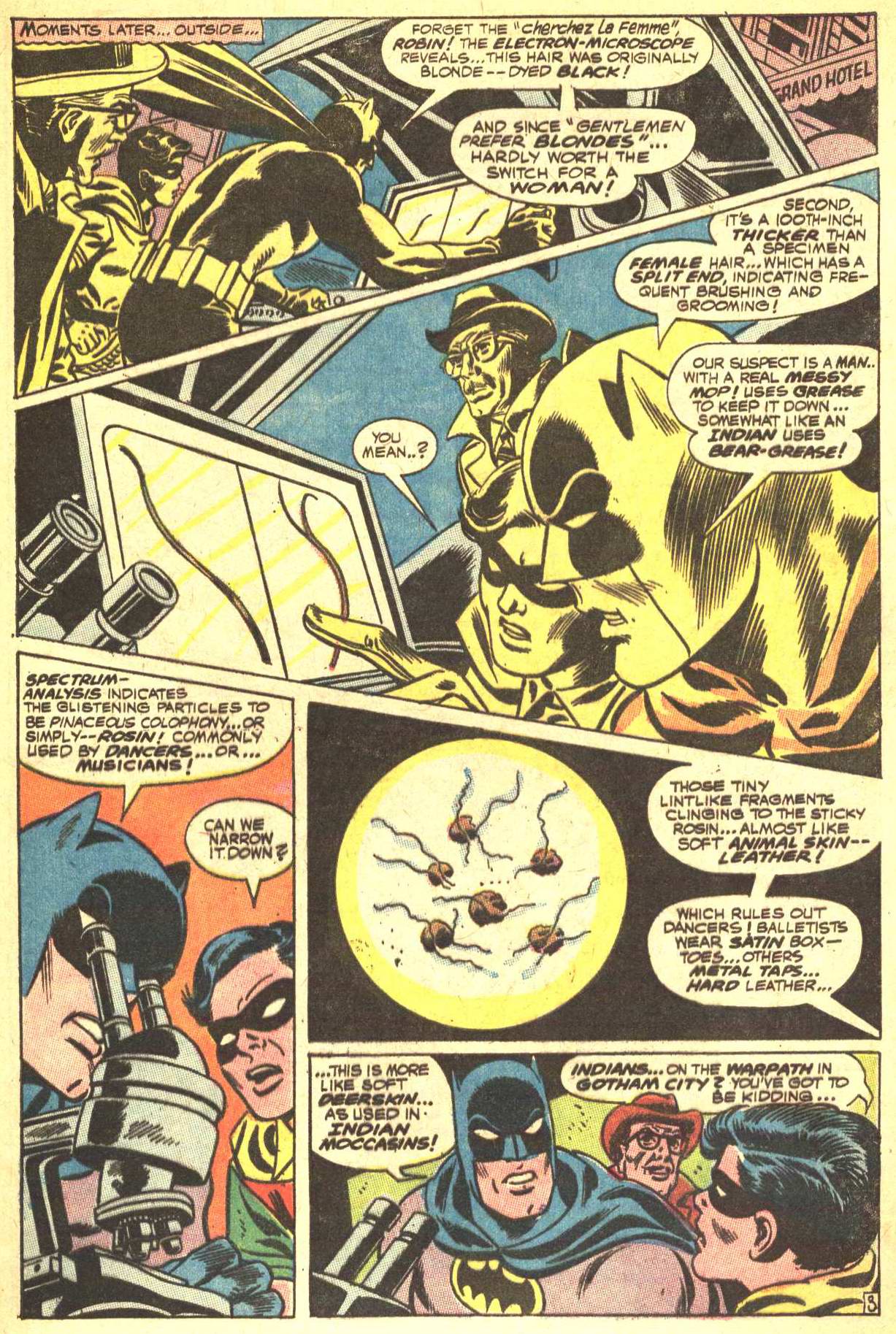

What’s more, Frank Robbins really played up the World’s Greatest Detective angle. Robbins’ warped imagination came up with creative crimes – and while these were not always realistic, the clues given to the reader were fair. Even his most conventional mystery tale, ‘Legacy of Hate!’ (a well-executed whodunit set in an apparently haunted castle where a ghostly knight is out to kill Bruce and a bunch of far-removed Wayne relatives), finishes with a twist that sets it apart from mere Scooby Doo-esque shenanigans.

Batman’s methods can be a bit unusual – such as in the underrated ‘Challenge of the Consumer Crusader,’ where he pretends to be the victim’s ghost in order to extract a confession from a suspect – but hey, the guy dresses up like a bat, so we already knew that he had an idiosyncratic approach to crime-fighting. Regardless, you can find plenty of clever detective fiction in these comics. This is not just true for Robbins’ later output, which increasingly consisted of straight up, gloomy crime stories. In one way or another, from early on even his wackiest scripts tended to include some kind of surprise reveal as well as advanced deductive reasoning…

Batman #206

Batman #206

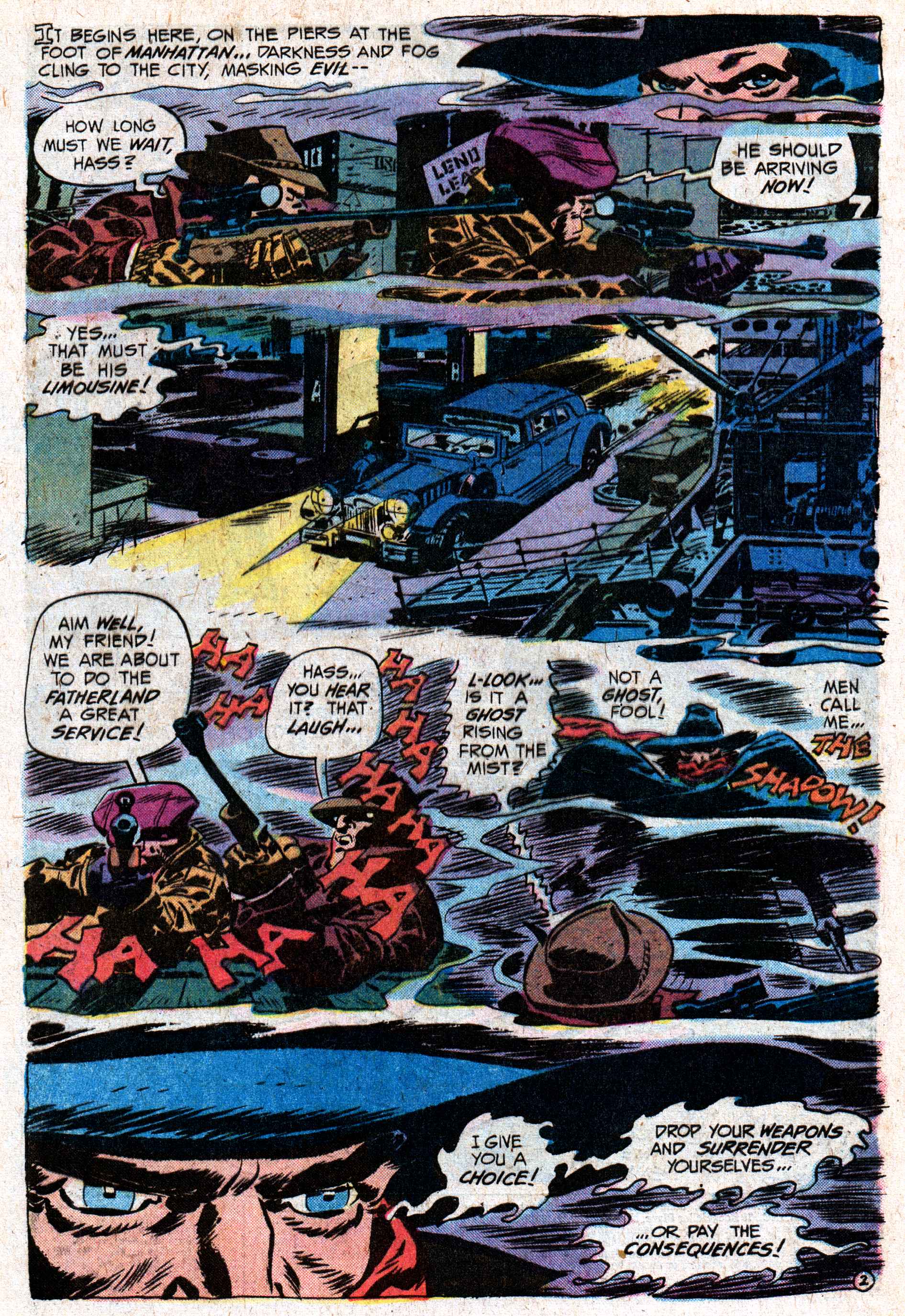

Robbins also illustrated a few of his comics. He was great at it, with a pre-Darwyn Cooke angular style and feathery linework evocative of 1950s’ cartoon advertisement. As an artist, Robbins’ high point is perhaps the truly moody visuals he produced for a number of issues of the Denny O’Neil-scripted version of The Shadow:

The Shadow #5

The Shadow #5

Robbins’ art was of course strikingly different from the mainstream Batman artists of the time, whose figures were comparatively much more photorealistic. However, his noirish pencils fitted perfectly well with somber crime stories, such as the cat-and-mouse antics with a methodical killer in ‘Forecast for Tonight… Murder,’ or the hardcore race riot and Attica-like prison revolt of ‘Blind Justice…Blind Fear!’

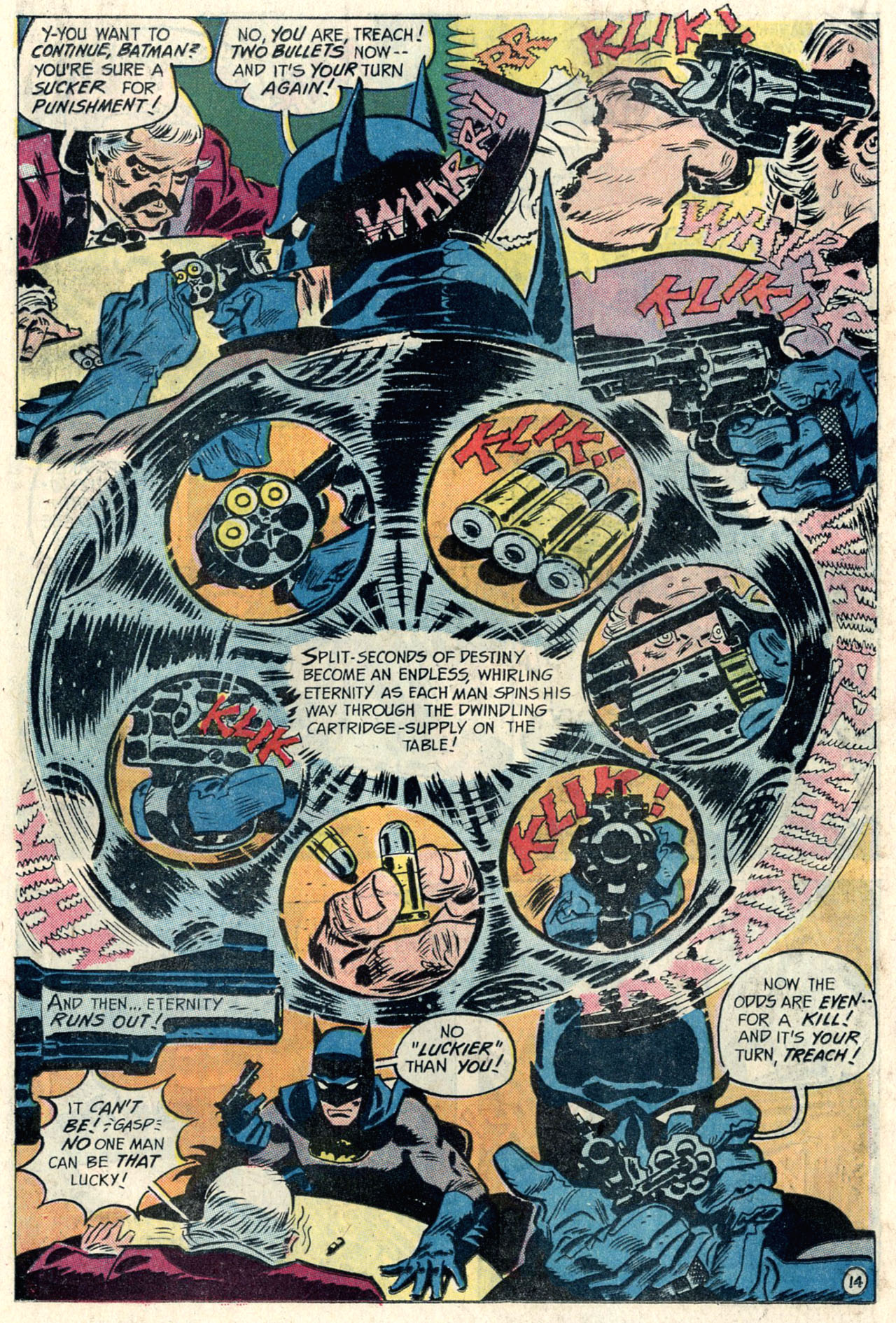

For my money, Robbins’ greatest accomplishment was ‘Killer’s Roulette!’ The issue starts with the world’s unluckiest cat burglar: first he bumps into an armed victim, then he realizes the man he intended to rob has committed suicide over gambling debts, and then Batman barges in. As if things weren’t bad enough, the burglar takes the dead man’s gun and tries to shoot the Dark Knight – always a bad idea. Soon Batman finds himself investigating a gambling network, leading up to one badass game of Russian roulette:

Detective Comics #426

Detective Comics #426

Frank Robbins’ work may have had ups and downs, highs and lows, and may not always have been on the right side of history. But every time I look at this page, all is forgiven.

He was writing and draw Batman before O’Neal/Adams, it was his work that first brought maturity to Batman.

I’m late to the party but I really enjoyed this article. I had The Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told as a kid. I’m a huge Neal Adams fan so Robbins’ art didn’t appeal to me at the time. I’ve really grown to love his style over the years. Pre-Darwyn Cooke is the best description of his art that I’ve heard. Great article!