The previous post in Gotham Calling’s tour of Cold War cinema had plenty of films about the conflict’s expansion to the Third World. Today’s installment extends the same motif, but it also gradually engages with one of the consequences of these new fronts, namely the collapse of détente and the re-escalation of the nuclear threat, especially after Ronald Reagan came to power. Once again, these are pessimistic times and you can see it on the screen.

91. Apocalypse Now (USA, 1979)

It took a few years for Hollywood to dare imagine the battlefields of the Vietnam War, an event whose scars on the US were literal (thousands of dead, maimed, and traumatized soldiers), social (deeply divided public opinion, with massive anti-war protests and a flourishing counterculture), national (large-scale military defeat and ethical loss of the heroic image earned in WWII), and geopolitical (discrediting the ‘domino theory’ that had justified fighting Vietnamese revolutionaries in the first place). When the gates opened, though, they flooded cinema with countless war movies, including a bunch of highly regarded masterpieces chronicling the American experience of the conflict (albeit with little to say about the Vietnamese perspective), from The Deer Hunter to Full Metal Jacket. None of them, however, had an impact comparable to Apocalypse Now’s immersive, psychologically haunting river journey towards Cambodia, politically ambiguous as it is (2001’s Redux version added a bit more historical context). Despite the fact that Francis Ford Coppola shot the whole thing like a trippy spectacle full of grotesqueries – or, more likely, precisely because of this – the film has firmly established much of the imagery, soundtrack, and lingo associated with this conflict ever since (‘Charlie don’t surf!’).

92. The Life of Brian (UK, 1979)

Along with spy thrillers and science fiction, sword & sandal epics were the other big genre that loudly splattered Cold War rhetoric across the screen, staging spectacular revolts against the state tyranny of ancient Roman and Egyptian dictators who opposed religious freedom, ranging from Cecil B. DeMille’s bluntly anti-communist biblical blockbusters to the leftist revisionism of Spartacus (a production that ended up playing a significant role in ending the Hollywood blacklist). I left out those movies as too allegorical (even though Ten Commandments opens with DeMille directly explaining the themes to the audience), but I can’t resist including the more openly anachronistic The Life of Brian, which mercilessly mocks that strain of religious cinema (and religion itself) as well as Middle Eastern conflicts and the sort of New Left terrorism seen in La chinoise. Indeed, even though it’s set in the 1st century, Monty Python’s classic comedy – about a man born in the stable next door to Jesus Christ’s – did much to popularize a very contemporary take on revolutionary politics… At the time, it pissed off conservatives, but nowadays its iconoclastic resonance has probably shifted, as the film memorably makes fun of radical movements (‘Judean People’s Front?! We’re the People’s Front of Judea!’), anti-imperialism (‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’), and identity politics (‘I’m not oppressing you, Stan. You haven’t got a womb.’).

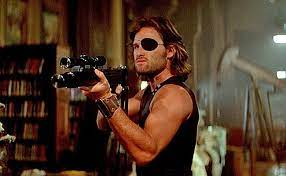

93. Escape from New York (USA, 1981)

The first of two 1981 dystopias that instantly defined pop culture’s vision of a hellish future, Escape from New York is set in 1997, when not only has the Cold War turned hot, but the whole of NYC has become a huge maximum security prison populated by gangs and madmen. This is where the hilariously badass inmate Snake Plissken is assigned with a mission that may make or break world peace… Yep, although made in the USA, this movie feels straight out of a 2000 AD comic!

94. The Road Warrior, aka Mad Max 2 (Australia, 1981)

A little over two decades after On the Beach, we get another tale about the aftermath of nuclear war set in Australia… and this time with even more car action! Probably the most influential post-apocalyptic movie ever, The Road Warrior revolutionized the subgenre by approaching it as a neo-western (complete with gay biker punks in lieu of Indians) where scavengers fight to the death for petrol in a lawless wasteland. Besides spawning a whole sub-industry of schlocky Italian B-movies (I have a special fondness for The New Barbarians/Warriors of the Wasteland), The Road Warrior got a sort of sequel (the continuity in this series has always been pretty loose) a few years later, Mad Max beyond Thunderdome, which was almost as iconic and arguably even weirder, but nevertheless similar in style, so I’m keeping that one off the list to make room for more diverse material… And yes, these films weren’t the first to relocate western tropes to a dystopic future, but none of what came before had a comparable impact. (That said, I’m pretty sure 1975’s The Ultimate Warrior did inspire the most infamous scene from Batman’s ‘Ten Nights of the Beast.’)

95. First Blood (USA, 1982)

The ultimate Vietnam-War-comes-home movie (an omnipresent theme from the very first scene), First Blood is both a raw, exhilarating action fest (with traces of horror in the forest sequences) and a shockingly powerful dramatization of a fucked up generation of drafted men taught to kill and sent abroad to inflict and suffer violence, only to come back to a society that despised them. The film is less balanced than the source novel, but it’s even farther apart from the jingoistic, militaristic sequels – those who only know the latter will no doubt be surprised by the politics of this first Rambo picture, with its ferocious indictment of homegrown small-town intolerance, of a despotic and sadistic police force, and of the traumatic impact of war.

96. Born in Flames (USA, 1983)

As mentioned in a previous post, along with all the dystopias where the Cold War just escalated until breaking point, there were also films that imagined alternative futures where political confrontation evolved in more original ways. The starting point for the punk feminist sci-fi/agitprop Born in Flames is that a ‘war of liberation’ turned the US into a socialist democracy ten years ago, but women and minorities continue to (literary) fight for their rights. Writer-director-producer Lizzie Borden delivers a guerrilla filmmaking tour de force as well as well as an inventive revolutionary polemic with an ending that has only grown in shock value… and an awesome soundtrack!

97. Under Fire (USA, 1983)

The Nicaraguan Revolution as seen from the perspective of three US journalists deciding how neutral they can remain. Yes, this is one of those Hollywood dramas where bloody real-world conflicts are put in the service of stories mostly focused on the problems of white North-American leads (which, I suppose, is itself symptomatic of the kind of Cold War mindset that saw much of the globe as supporting players in Washington’s crusade). That said, on top of being intelligently written and acted, Under Fire does convey a compelling, Graham Greene-esque sense of place and history. Plus, it’s hard not to see in this liberal film looking back at 1979 a response to the counter-revolutionary US policy towards Nicaragua implemented in the meantime, by the Reagan Administration.

98. WarGames (USA, 1983)

Trying to hack the latest computer game, a teenager stumbles into a military AI program and accidentally kicks off World War III. This is the kind of 1980s’ fun, smart teen adventure celebrating consumerism in the guise of rebellion that was later emulated by Stranger Things – and while the dated technology now lends it a retroactive/nostalgic charm, it also works as an efficient sci-fi thriller engaging with classic themes of the genre (human vs artificial intelligence) along with more topical issues about whether a nuclear war is winnable and whether game theory can prevent or escalate conflict (sure enough, just a few months after the film’s premiere, NATO’s Able Archer war game was apparently misinterpreted by the Soviets and brought the world once again to the brink of thermonuclear war).

99. Nineteen Eighty-Four (UK, 1984)

For the purposes of this list, you might think earlier adaptations of George Orwell’s dystopia would be more interesting, as they played up the obvious parallels with Stalinism (especially the 1956 version, secretly funded by the CIA). Yet this is my favorite take on the material: like Moore & O’Neill in The Black Dossier, writer-director Michael Radford returned 1984 to 1948, complete with postwar rubble and food rationing, resulting in an impressively grimy, rusty-looking, and significantly faithful – despite the somewhat ambiguous closing shots – rendition of the source novel (itself a foundational Cold War text). Sure, the notion that a continuous state of war empowers authorities to control and oppress citizens was still topical in the eighties, but, more than just another allegory about – existing or potential – totalitarianism, this Nineteen Eighty-Four feels like a period piece set in a retro-futuristic alt history where Orwell’s specific nightmares of atomic conflict and rise of authoritarian rule in Britain did immediately take place (which, in turn, perfectly suits the theme of mass media controlling the past).

100. Red Dawn (USA, 1984)

A different type of dystopia. The opening text offers a right-wing nightmare scenario: ‘Cuba and Nicaragua reach troop strength goals of 500,000. El Salvador and Honduras fall. – Green Party gains control of West German parliament. Demands withdrawal of nuclear weapons from European soil. – Mexico plunged into revolution. – NATO dissolves. United States stands alone.’ After this, Red Dawn doesn’t waste much more time establishing its preposterous premise: the Soviets, Cubans, and Nicaraguans invade the US, so the North Americans get to demagogically play the underdog as a group of high-school teenagers engage in guerrilla warfare against the occupiers, turning the nightmare into a libertarian wet dream. If I didn’t know about John Milius’s fascistic politics, I’d assume he had written and directed this schlockfest as a deranged parody of US jingoism and Cold War alarmism… Regardless, the film never fails to make me laugh! (This ridiculous tale of small-town armed resistance remains the ultimate wish-fulfilment fantasy of alt-right militias, having even led to an uninspired Obama-era remake, with North Korea as the new villain).