Welcome back to Gotham Calling’s ongoing list of notable films that gave an audiovisual expression to the Cold War (previous installments here and here). This time around, many of my choices are less explicit, as by the mid-1950s sci-fi horror became one of the key genres to tap into growing nuclear panic (especially following the testing of the powerful H-bomb).

That said, as the Cold War expanded geographically, you also get increasingly different settings – and different national cinemas filming the conflict’s impact from a more personal, close-to-the-ground perspective. The movies I selected this time, apart from being interesting on their own, are also meant to illustrate this wider contrast.

21. Godzilla (Japan, 1954)

Last time, we finished with Animal Farm – and this time we’ll start with a couple of very different animal-based allegories (‘animallegories’). The most influential monster picture of all time posits a blatant indictment of nuclear weapons. The original Godzilla is so moody (not least because of the music), downbeat (despite the cathartic appeal of destruction), and disturbing (if you look at it from the perspective of then-recent Japanese traumas) that you wouldn’t have expected this somber horrorfest to spur a franchise with such kid-friendly connotations.

22. Them! (USA, 1954)

In this Hollywood contribution to the ‘creature feature’ subgenre the symbolism is less straightforward, reflecting the double fear of homegrown radiation and of attacks on domestic soil by an enemy that cannot be reasoned with… and which can only be fought if all national institutions play their part. I’ve previously expressed my fondness for Them! here.

23. I Live in Fear (Japan, 1955)

A Tokyo businessman is so fearful of the hydrogen bomb that he tries to move all of his family (including a couple of mistresses and illegitimate children) to Brazil. I Live in Fear offers an intriguing snapshot of 1950s’ Japan (rather different from Godzilla!), courtesy of Akira Kurosawa’s restless camera and mise-en-scène…

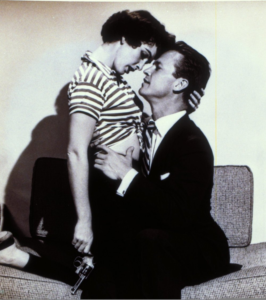

24. Kiss Me Deadly (USA, 1955)

Another recurring recommendation in this blog… Loosely adapting a hardboiled detective novel by Mickey Spillane, Kiss Me Deadly both subverts the source material and injects a whole new conspiracy angle that firmly ties the story into the nuclear era.

25. Piagol (South Korea, 1955)

Refusing to accept the 1953 armistice, a North Korean unit engages in a mountain-based guerrilla and gradually self-destructs in this very gritty war movie, whose terse style and ingenious cinematography make the most out of the rugged landscape. Piagol would be interesting enough as a twisted South Korean depiction of the recent (and, technically, ongoing) enemy… What makes it an even more stimulating historical object is the fact that the film was initially banned because the Seoul authorities considered that it overly humanized the communists, so the director had to add a patriotic flag to the final shot to get it approved.

26. The Prisoner (UK, 1955)

The Prisoner delivers a cerebral, Kafkaesque nightmare in the form an unnamed dictatorship where a cardinal accused of treason has an enthralling battle of wills against his interrogator. While touching on key points of Western indictments of the Eastern European regimes (political persecution, psychological torture, anti-clericalism), the film actually turns into a smart character study, not least because of Alec Guinness’ nuanced performance.

27. Sky Without Stars (West Germany, 1955)

Sky Without Stars pulls at your heartstrings through a love story in divided Germany, as seen from the West. It works powerfully on both literal and allegorical levels: more than the communist system itself, the main source of (individual and national) tragedy are all the different borders keeping people apart. Manipulative, yet affecting.

28. A Berlin Romance (East Germany, 1956)

A Berlin Romance pulls at your heartstrings through a love story in divided Germany, as seen from the East. With its young protagonists searching for their place in the world, whether in West or in East Berlin, this is arguably the most sensitive of a brief surge of productions – made in the context of de-Stalinization – observing and even criticizing the GDR’s shortcomings (albeit still expressing faith in socialism). Manipulative, yet affecting.

29. China Gate (USA, 1957)

Linking up Asia’s conflicts, this bonkers adventure has veterans from the Korean War join the French Foreign Legion in 1954 Indochina in order to keep up the good fight – with the help of a sultry smuggler called Lucky Legs. China Gate is so brazenly anti-communist, colonialist, and committed to domino theory that it has to be seen to be believed (the opening narration alone is an entire treaty!), its melancholic ending coming across as even more tragic once you consider what lays ahead. That said, this utterly glorious mess is yet another gem written and directed by Sam Fuller, whose visceral style means that every shot is bombastic and, every time you think you have the film figured out, it’s bound to surprise you in some way (like when Nat King Cole starts singing the movie’s theme song among a village’s ruins, or when Lee Van Cleef shows up as a loquacious schoolteacher-turned-warlord praising Ho Chi Minh and dreaming of working in Moscow…). Seriously, this could be a companion piece to the first arc of Fury MAX: My War Gone By! Plus, like many of Fuller’s pictures, it revolves around an idiosyncratic examination of racism.

30. Enemy from Space, aka Quatermass 2 (UK, 1957)

Like giant monsters, 1950s’ extraterrestrial threats (especially depersonalization narratives) are often read as a quintessential manifestation of Cold War anxieties on screen, so I had to include at least one entry into this emblematic cycle. My pick is this sequel to the – also pretty awesome – cult classic The Creeping Unknown (aka The Quatermass Xperiment). Enemy from Space revisits – and expands – the original’s premise about an alien menace, now with an added conspiracy threat that puts a very British spin on Invasion of the Body Snatchers: as argued by Matthew Jones, if US sci-fi produced metaphors about communism infiltrating small communities, here the villains seem to represent the mole-ridden UK establishment, which in the climax is pitted against a mobilized working class.