This is the latest installment of Gotham Calling’s 12-part journey through Cold War cinema (if you’re only joining us now, you can find the previous installments here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). It’s also probably the most eclectic of the lot, both in terms of international scope and in terms of sheer range of styles, including various independent productions.

If there is one common element is that by the time we reach the 1970s films generally become way more crowded, dirtier, and revolted against the world that the Cold War has created. For all the talk of superpower détente and Eurocommunism (with some Western European communist parties rejecting the USSR’s model and embracing moderate social democracy), these are angry times, as Vietnam, Watergate, and authoritarian/revolutionary/counter-revolutionary politics linger in the background of practically every one of these films.

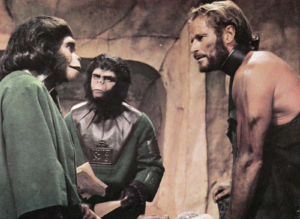

81. Planet of the Apes (USA, 1968)

Charlton Heston plays a misanthropic astronaut who both regains and re-loses faith in humanity when he finds himself stranded on a planet ruled by chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. Cold War themes (especially McCarthyism) are all over the unapologetically pulpy Planet of the Apes, but they reach a peak in the deservedly iconic ending.

82. The Joke (Czechoslovakia, 1969)

Through flashbacks, we come to know the story of a man punished back in his student days for a jokey remark on a postcard… and his present-day revenge plot. Although completed already after Warsaw Pact troops had crushed Czechoslovakia’s process of liberalization, The Joke is a clear product of the ‘Prague Spring’ that preceded the 1968 invasion, offering a scathing look at hardline communists and the regime they put in place, with occasional touches of black comedy. Based on a Milan Kundera novel, the critique isn’t subtle, but the central performances are generally understated and the direction quite enthralling, with acidic irony provided by clever cross-cutting between eras.

83. Z (France/Algeria, 1969)

Z’s thinly fictionalized account of the growing strength of anti-communist military officers in Greece is a testament to the power of cinema, as director Costa-Gravas turns detailed, often technical discussions into an engrossingly gritty, dynamic, and spellbinding political thriller.

84. Bananas (USA, 1971)

An absurdist parody about a doofus from New York who inadvertently gets embroiled in a Latin American revolution, Bananas now feels like an odd fossil not only from the Cold War, but from a seemingly distant era when Woody Allen was widely beloved, artistically daring, anarchically political, and very funny. Like all of his early slapstick farces (i.e., pre-Annie Hall), this is pretty much a naughty live-action cartoon where the laughs are quite hit-and-miss – and while there aren’t as many hits as in some of the others, it picks up momentum in the final stretch. In any case, the refreshingly carefree way Allen turns Che, Castro, Hoover, Third World repression, CIA-backed conflicts, and the trial of the Chicago 7 into silly surrealism (much like he did with the Nixon administration in the TV mockumentary Men of Crisis: The Harvey Wallinger Story, pulled from the schedule at the last moment by a fearful PBS) earns Bananas a place on this list, despite the occasional cringe. (Bananas also features Sylvester Stallone’s first appearance on the list… Needless to say, you will see him again!)

85. Punishment Park (USA, 1971)

In response to the escalating anti-Vietnam War protests, President Nixon decrees a state of emergency based on the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950, enabling the federal authorities to round up members of the counterculture and send them off to the desert where they serve as practice for the police and the National Guard. Set in a (slightly) alternate history but shot in an impressive cinéma vérité style (complete with long stretches of improvisation by non-professional actors), Punishment Park is another amazing fake documentary by Peter Watkins, this time encapsulating the political polarization in the US.

86. State of Siege (France/Italy/West Germany, 1972)

Tupamaros’ kidnapping of the Brazilian consul in Uruguay and of an official of the US Agency for International Development serves as a springboard to expose the CIA’s dirty history of backing anticommunist coups and violent repression across Latin America. Despite the overlapping topic, tone-wise this is the flipside of Bananas. More concerned with conveying macro-structures than with zooming in on individual psychologies, State of Siege is shot in the same dry, procedural style as Z – in fact, once again, this could’ve succumbed under the exposition-heavy polemic format were it not for Costa-Gravas’ absolutely gripping direction. (In turn, David Miller’s attempt to do a Costa-Gravas-like semi-documentary thriller about the JFK assassination, 1973’s Executive Action, sorely lacked this directorial verve.)

87. The Crazies (USA, 1973)

Young George Romero had a keen instinct for socio-politically charged horror. In The Crazies, he tapped into the era’s paranoia about government cover-ups, had the arms race literally drive people insane (and/or make them sound insane, thus furthering the motif from Europe ’51 and The Spies), and made small-town America a target for the kind of military intervention deployed abroad. Shot with hand-held camera immediacy (back before this became a cliché) and lots of shouting, the result is a phenomenal, intensely disturbing, and frenzied ride of a movie.

88. The Spook Who Sat by the Door (USA, 1973)

There aren’t many blaxploitation movies about the Cold War, but boy does The Spook Who Sat by the Door make up for the rest of the lot. In the satirical first act, the CIA reluctantly agrees to train a black man as part of a cynical PR campaign. Then, in the incendiary rest of the film, he repurposes the company’s playbook of dirty tricks to kickstart an insurrection at home, trying to force the US authorities to choose between fighting African Americans at home or the commies overseas! Apparently, the result was so controversial that the movie was suppressed for years, although it eventually resurfaced and gained a new recognition.

89. The Front (USA, 1976)

This dramatization of the 1950s’ blacklist made such an impression on me when I was a teen that I still appreciate it despite the didacticism and liberal sentimentality, especially two unforgettable performances: Woody Allen as a despicable yet charming lumpen and Zero Mostel as a star comedian falling from grace, the latter’s eager overacting heartbreakingly hiding a crushed soul. The film fulfills two functions on this list. First, since those involved in the production had themselves been blacklisted (including Mostel), there is an autobiographical layer that makes this an authentic-ringing document of the McCarthyist era, for once zooming in on the less glamorous milieu of New York network television rather than on Hollywood. Secondly, The Front shows how far the US had come since the ‘50s: the so-called Cold War consensus – and the blacklist itself – now such a thing of the past that the HUAC’s tactics could be exposed directly, albeit timidly… This is still a rather understated, personal account of an impactful systemic issue, perhaps out of fear/awareness that the American public wasn’t yet interested in fully confronting the sins of the recent past, hence the choice of using Allen’s selfish schmo as the POV character (which actually makes the movie both more interesting and wryly amusing, giving us an ambiguous, flawed protagonist rather than a romanticized victim).

90. Illustrious Corpses (Italy/France, 1976)

The investigation of a judge’s murder takes a police inspector, slowly but surely, into a tour of conspiracy theories against the backdrop of Italy’s ‘years of lead’ (when the far-left Red Brigades waged a campaign of armed struggle) and ‘historic compromise’ (when the reformed Communist Party made an alliance with the right-wing Christian Democracy). Very deliberately paced and mostly shot through wide angles that underscore the characters’ relative smallness and vulnerability to larger forces at play, Illustrious Corpses is a Pakula-worthy masterwork of paranoid cinema, albeit with a fascinating Italian slant, provocatively subverting Gramsci’s famous line: ‘To tell the truth is revolutionary.’