If you read last week’s post (or just this post’s title, really), you know I’ve been looking at some of the many, many depictions of sex workers in Batman comics. This week, let’s focus on the sinuous paths of two of them.

Catwoman #1

Catwoman #1

Frank Miller first linked Catwoman to prostitution in his 1986 opus The Dark Knight Returns, where an older Selina Kyle runs an escort business, but that’s an imaginary tale set in a possible future. Batman: Year One’s reboot, published the following year, was a more radical move, taking a colorful mainstream character who had been a part of popular culture since 1940 and giving her a sex worker background even as this version of her was expected to continue to star in upcoming comics. You may find it tasteless and inappropriate or perhaps a clever extrapolation of the fetishistic imagery that had already been built into the character over the years (the tight outfit, the dominatrix whip…) – especially since Julie Newmar’s sexy performance in the 1960s’ Batman TV show – but in any case it was a sure mark of that moment in time, in the late eighties/early nineties, when DC began to toy with the idea of gearing even its silliest properties towards adults (a trajectory that would soon lead to their Vertigo imprint). Seriously, this was a time when you could compare a random Batman issue with the latest sleazy crime novel (like Gerald Petievich’s Shakedown, just to name a nifty one) or with the VHS of a gritty action movie (something like, say, Dwight H. Little’s Rapid Fire) and they would have more in common than not.

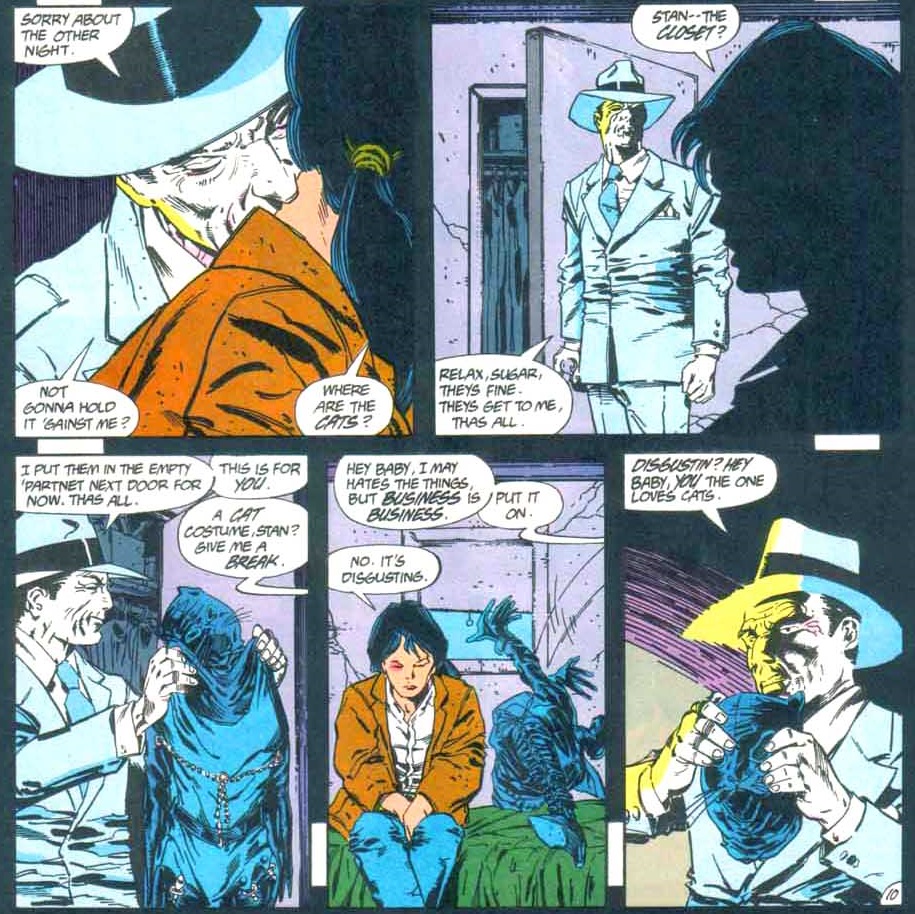

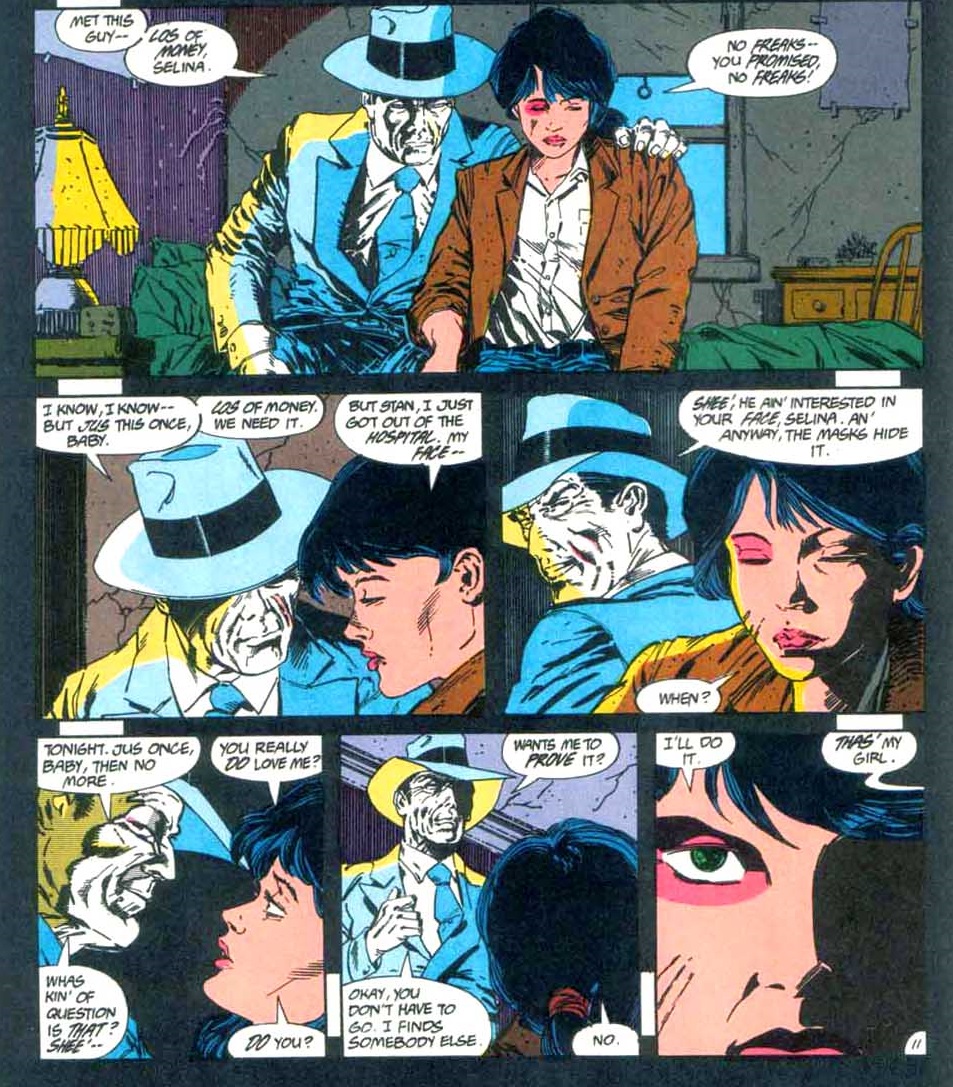

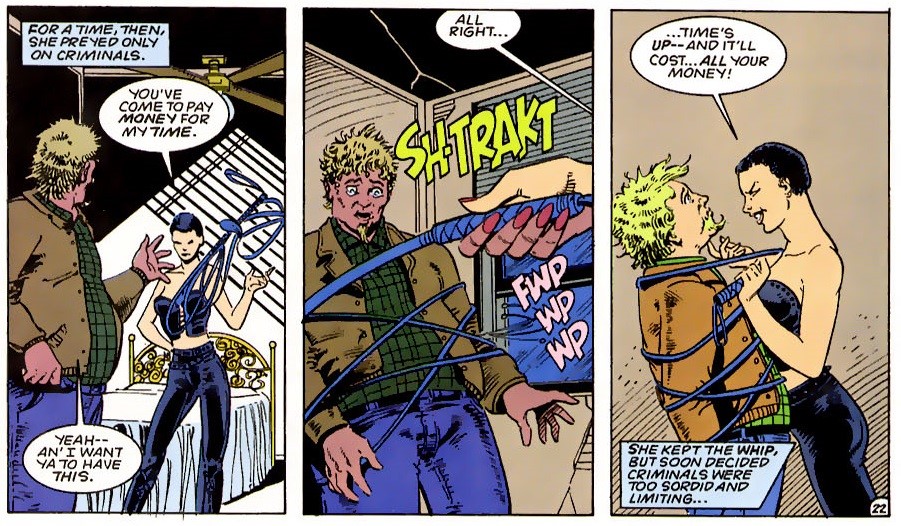

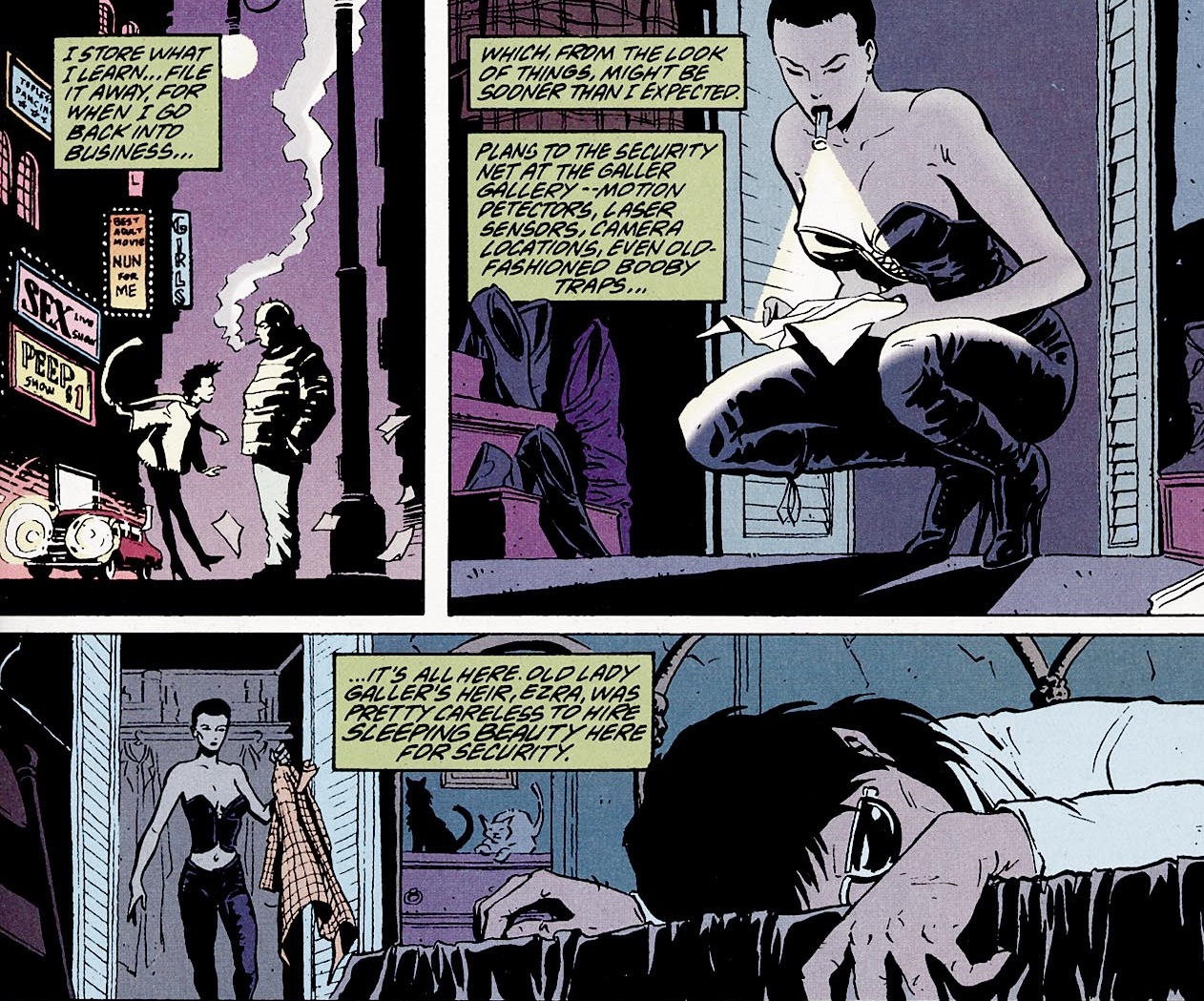

Mindy Newell ran with this in her Catwoman mini-series (later collected as Catwoman: Her Sister’s Keeper). Stan the Pimp was the main villain of the piece, now retconned as a key figure in Catwoman’s origin, even down to her costume choice (as shown above). If Miller had chosen to present Selina as an empowered prostitute (sort of anticipating the self-reliant sex workers of his Sin City, years later), Newell began by emphasizing the manipulative, abusive relationship with Stan. This backstory gave a new context to the cool, confident character we know and love, as we learned that Selina had moved from a vulnerable position – and from feeling uncomfortable and threatened by kinky bondage – into a dominant, independent woman who took no shit (and who literally killed Stan). In other words, Catwoman wasn’t just strong; she was hardened by life. Her attitude towards the patriarchy in general and towards Batman in particular, like the way she used and embraced her sexuality (including her S&M look), gained a new meaning once you considered where she came from and what she was rebelling against:

Catwoman #1

Catwoman #1

Not everyone agreed with the change, at least at DC. When shaking up the DCU’s continuity through 1994’s Zero Hour crossover, editorial sought to retcon this aspect of Selina Kyle’s past. I’m guessing they were driven by a puritan mindset, typical of large corporations and mainstream commercial ventures, but there is a feminist case to be made in either direction. Catwoman was one of the few prominent female characters in DC’s roster at the time (she got her own ongoing series in 1993), so I can see why they didn’t want to reinforce pop culture’s traditional reduction of women to victims and/or sexual objects (the Madonna-whore dichotomy). Then again, empowering a former sex worker could be a progressive statement as well, using this iconic figure to tell the story of a woman who defines herself beyond her sexual history (or traumatic past).

Writer Doug Moench turned the whole prostitution thing into a front, part of a scam, which fit in with the classic motivations (i.e. robbing stuff) of this notorious cat thief…

Catwoman (v2) #0

Catwoman (v2) #0

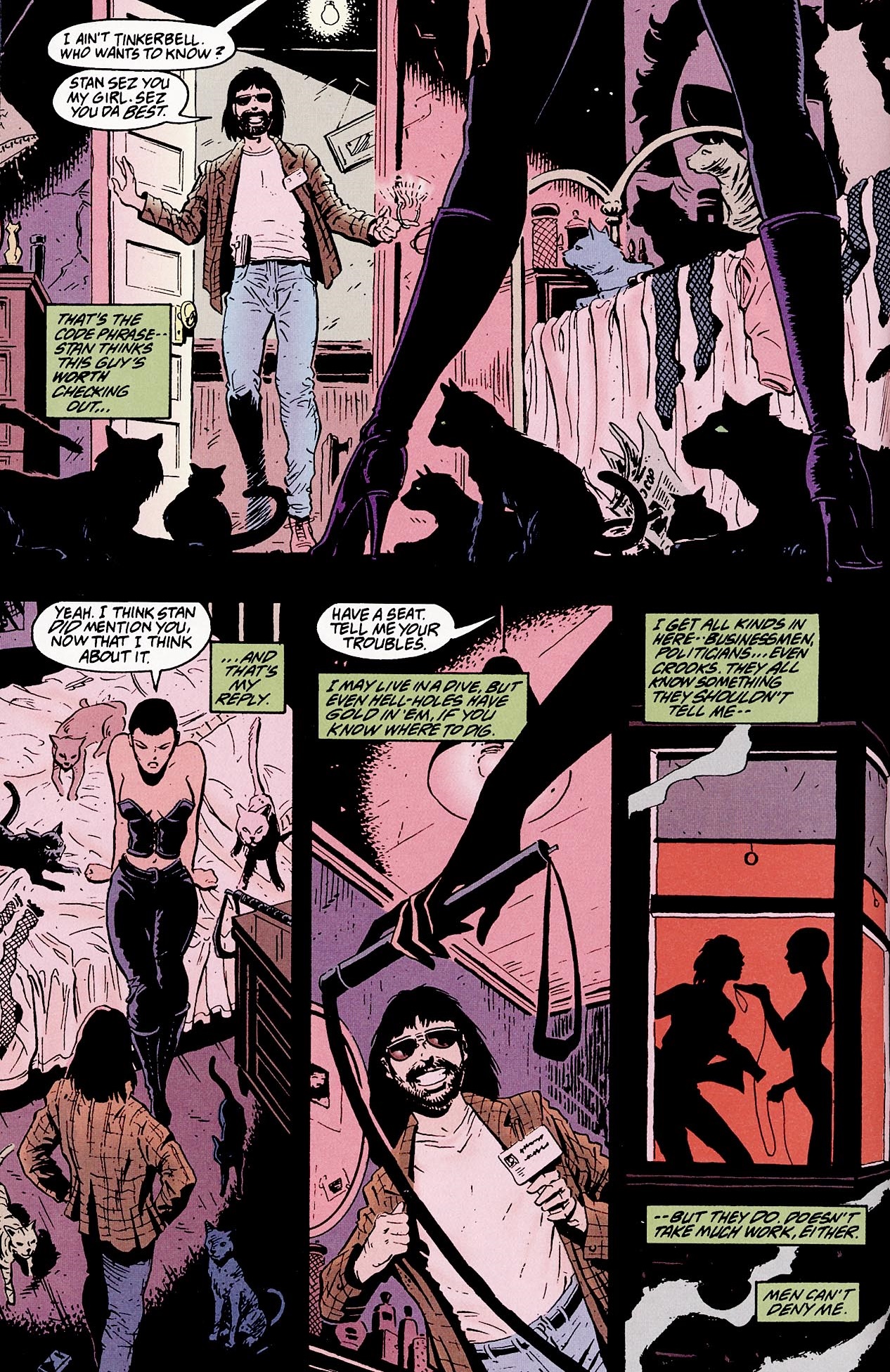

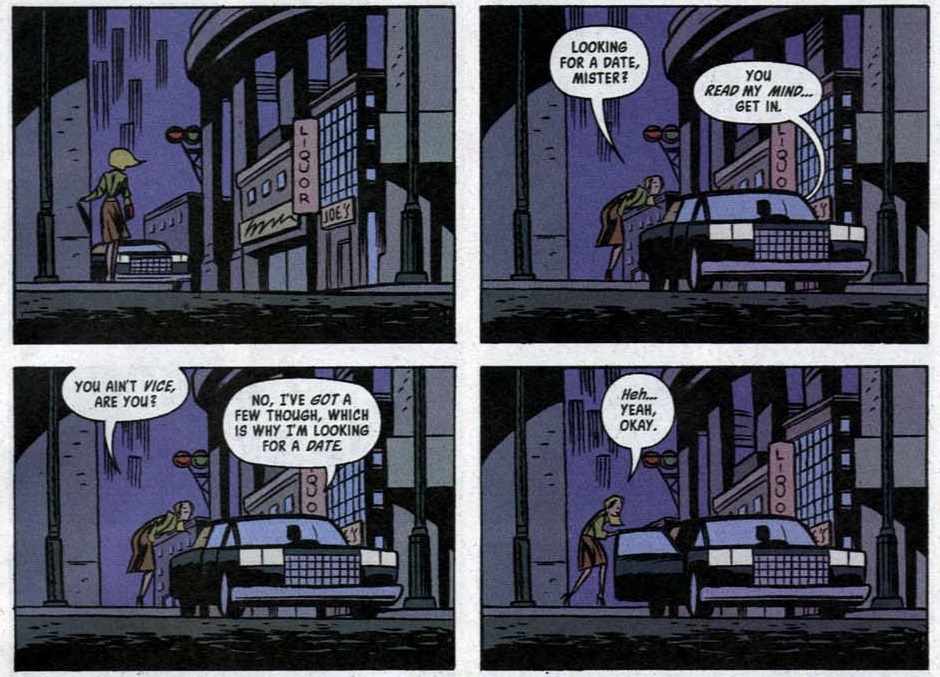

Just a year later, though, Jordan B. Gorfinkel muddied things up in an ambiguous ‘Year One’ flashback where Selina – while in hiding, trying to drop off the cops’ radar – did appear to have had a working arrangement with Stan the Pimp. Looking back, this was an era when the notion of badass women aggressively weaponizing sex was all over mass media (from Basic Instinct and The Last Seduction to GoldenEye), perhaps as a response to third-wave feminism. Indeed, increasing Selina’s agency, the implication now seemed to be that she had sex with clients, but she was more in control and ultimately exploiting them, rather than the other way around:

Catwoman Annual #2

Catwoman Annual #2

While I don’t think Catwoman *needed* this background (and most present-set comics ignored it anyway), it aligned well with the character. Whether as a villain or as an anti-hero, she was meant to have an ambiguous morality that didn’t match conventional values. The contrast with Batman’s black-and-white worldview has always been a key part of their relationship, as they constantly have to negotiate their attraction with their conflicting ideologies.

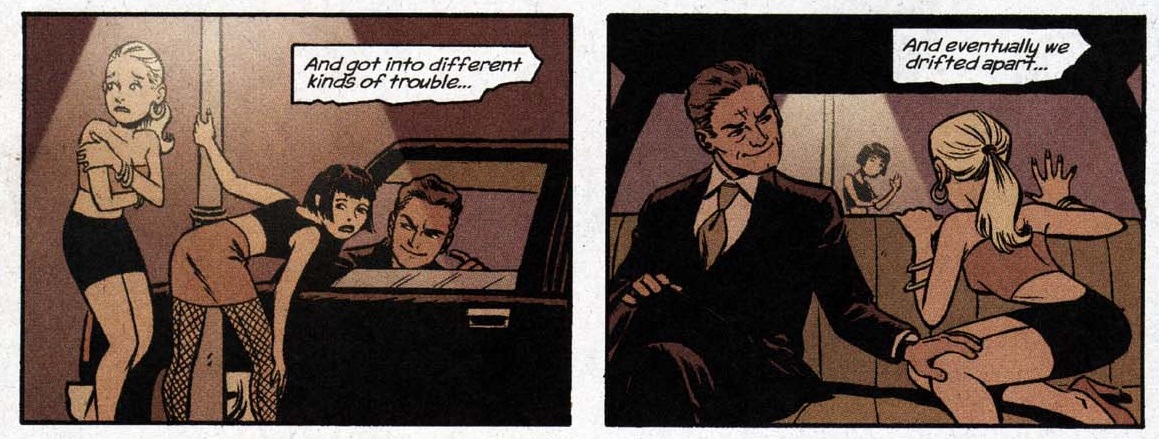

Perhaps Ed Brubaker and Darwyn Cooke felt the same. In 2001, they brought back much of the continuity of Catwoman: Her Sister’s Keeper in a big way, including the prostitution angle. In fact, sex work – like drugs – was a major theme in Brubaker’s whole Catwoman run, starting on the very first pages of the earlier issues…

Catwoman (v3) #2

Catwoman (v3) #2

The murder of streetwalkers like the one above convinced Selina Kyle to become a vigilante herself, protecting Gotham’s East End, particularly the sex workers when they were threatened by their clients or by the cops. Since neither Batman nor the authorities paid enough attention to these people, Catwoman took it upon herself to compensate for society’s prejudices, no doubt motivated by her own experience when she was younger.

Hell, as it turned out, when she was much, much younger:

Catwoman (v3) #12

Catwoman (v3) #12

While Catwoman’s posture towards sex workers wasn’t necessarily condescending, she was nevertheless critical of their way of life. Ed Brubaker’s run was as grim as they come, presenting a decadent, uninviting picture of this milieu. Indeed, one villain in particular was a traumatized former child prostitute motivated by revenge against Selina, whom she blamed for having previously failed to acknowledge her pain.

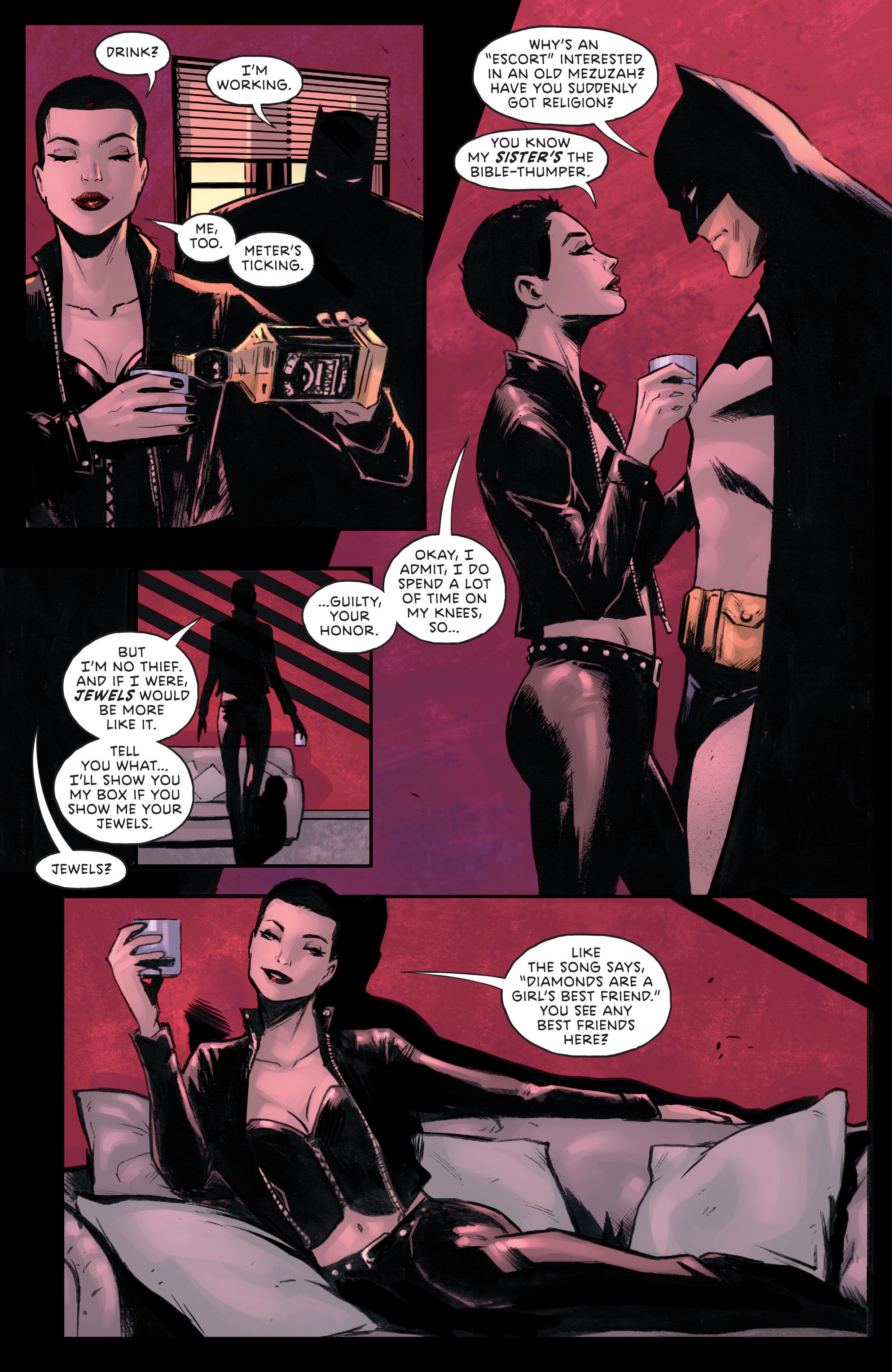

In turn, when Mindy Newell wrote a short sequel to Her Sister’s Keeper – which came out last year – she approached the topic in a much more lighthearted, non-judgmental way, complete with fun, campy dialogue:

Catwoman 80th Anniversary 100-Page Super Spectacular

Catwoman 80th Anniversary 100-Page Super Spectacular

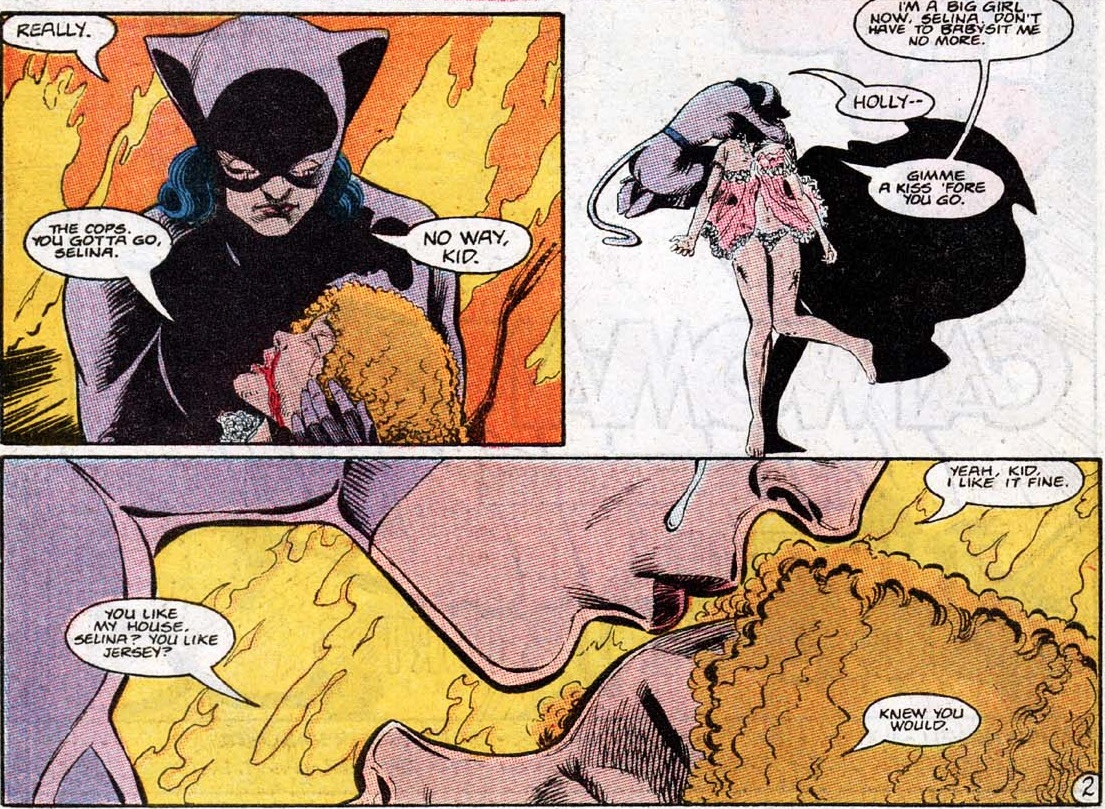

For a relatively less ambivalent portrayal of prostitution, we turn to the case of Holly Robinson, Selina Kyle’s 13-year-old street colleague in Batman: Year One, who seemed to have a sort of Stockholm syndrome towards their mutual pimp. One of the most disturbing aspects of that book was the naturalization of Holly’s condition, with even Selina seeming pretty much indifferent to her companion’s age, even if she did make a point of bringing Holly with her when they left the business:

Batman #406

Batman #406

Mindy Newell stuck to this characterization in Catwoman: Her Sister’s Keeper. Selina was clearly protective of Holly Robinson, but she wasn’t too concerned about the possible traumatic effects of their previous job, to the point where she casually used the kid’s looks and reputation to set up a bait…

Catwoman #2

Catwoman #2

At the end of that mini-series, however, Selina’s sister – who was a nun – took Holly into a convent while Selina went on to pursue her criminal career as Catwoman. This led to one of my favorite character moments, which finally acknowledged the impact of Holly’s messed up childhood and the fact that transitioning into a new life was probably not going to be a smooth ride:

Catwoman #4

Catwoman #4

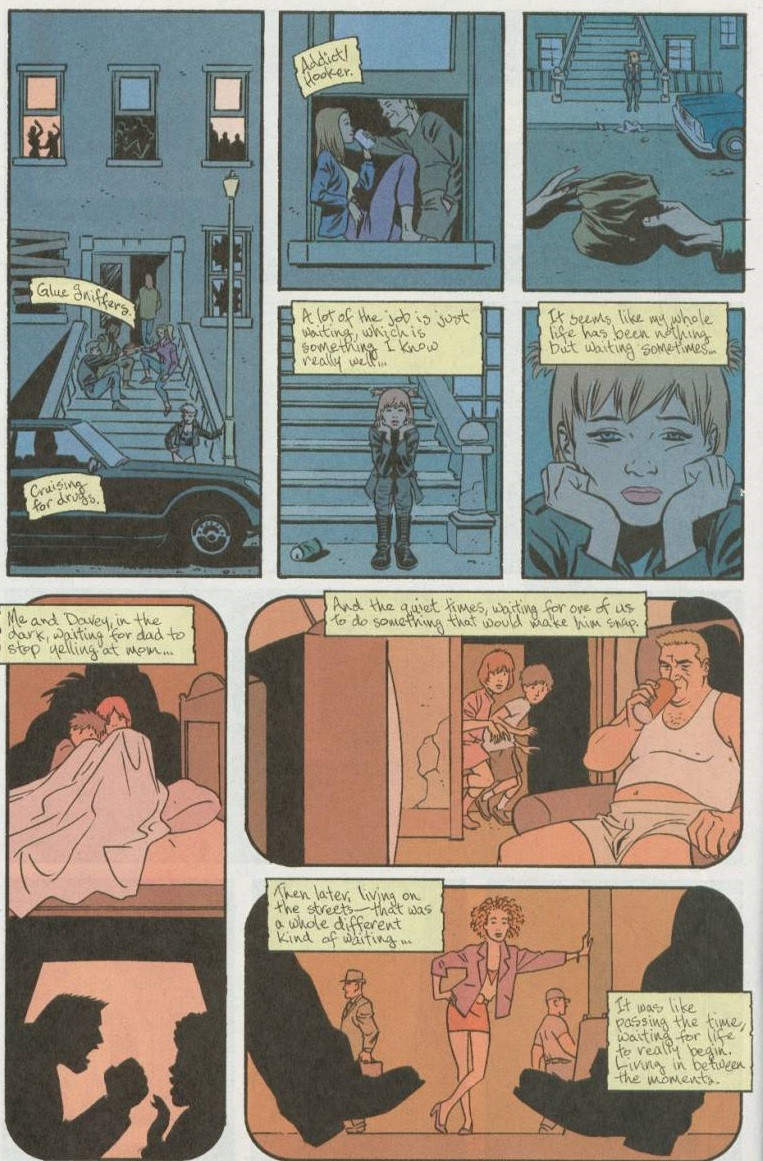

Curiously, the previous year (1988) had seen the publication, in Action Comics Weekly, of a brief Catwoman run where Mindy Newell had already shown us what lay ahead for Holly Robinson. Set years later, in the then-present (as opposed to Her Sister’s Keeper, which ran parallel to Batman: Year One), this run featured an older Holly who seemed relatively well-adjusted to a bourgeois lifestyle, having married a rich guy and moved to Jersey.

Unfortunately, she was a minor female supporting character in a comic, so you know what that means…

Action Comics Weekly #613

Action Comics Weekly #613

The fact that Holly died in a little-known installment of a weekly anthology published in the late eighties didn’t prevent Ed Brubaker from bringing back the character in 2002, alive and with a different life path since she had last been seen in Her Sister’s Keeper (he amusingly addressed this inconsistency in a metafictional two-page story from Catwoman Secret Files and Origins). In Brubaker’s version, Holly, now around 20 years old, was back to working the streets in Gotham’s East End, having left the convent (as retroactively foreshadowed in the scene from the previous scan) and drifted through a life of drug addiction.

Because Selina didn’t want anyone she cared about to be working on the street, she hired Holly to assist her in her vigilante mission instead, paying her to merely pretend to be in the life while actually acting as Catwoman’s eyes and ears on the ground. Throughout this run, Holly grew into an increasingly rounded and extremely likable character. Issue #6 is particularly impressive, dealing with the way Holly juggles being a recovering addict and hiding her secret gig as Catwoman’s sidekick from her girlfriend.

Catwoman (v3) #6

Catwoman (v3) #6

As it happened time and time again, mainstream comics proved unable to deal with such a rich character in a realistic way, so it was a matter of time before Holly Robinson received the superhero treatment: she went on to temporarily take over Catwoman’s mantle and later was trained to be one of Granny Goodness’ Female Furies before briefly receiving the powers of Diana, the Goddess of the Hunt. Good for her.

All in all, female prostitution has had a substantial presence in Batman comics, not just as a recurring visual feature of Gotham City’s landscape, but also as part of some of the franchise’s major works and character arcs. And while a lot of it is pretty clichéd, I’m glad that at least some sex workers have been allowed to grow into multifaceted cast members who aren’t reduced to this one aspect of their lives.