I won’t drift too far away and too often, but this year I want to widen the blog’s scope every once in a while. With that in mind, let’s shift gears for a bit and talk about John le Carré’s series of spy novels featuring the fictitious British counter-intelligence department known as the Circus.

When I say ‘shift gears,’ I mean it: not only are these not comic books, they are deliberately removed from the kind of pulp adventure sensibilities that inform most of the material I usually cover on this blog. John le Carré (who was himself an MI6 operative in the early 1960s’ West Germany [edit: In the previous decade, he had also worked for MI5.]) specializes in consciously anti-James Bond narratives, deglamorizing the UK’s secret services and complexifying the Cold War’s murky morality while privileging descriptions and long dialogues over violence, gadgets, and babes. It’s all perfectly personified by the recurring character of George Smiley, a middle-aged, overweight, cerebral agent, cuckolded by his wife.

Part of the reason I love these books so deeply is precisely the satisfaction of reading a sophisticated, revisionist take on the adolescent fantasies I grew up with (similar to what it felt like to first read Watchmen having grown up on much more naïve superheroes, or what it must feel like to read Criminal after a steady diet of Sin City). Another part has to do with the fact that, as a fan of superhero comics, I’m a sucker for sprawling, intertextual world-building. It’s not just that the Circus novels share characters – it’s that the focus keeps shifting in interesting ways, with one book’s lead sometimes turning up as a supporting player in another book, or a plot turn shedding new light on a previous story, or George Smiley’s evolution throughout the decades (including the weight of his marriage, always looming in the background) becoming increasingly symbolic of changing geopolitics…

George Smiley is a major player in John le Carré’s first couple of novels, 1961’s Call for the Dead and 1962’s A Murder of Quality. The earlier one – in which Smiley looks into the suicide of a Foreign Office civil servant whom he had recently interviewed for a routine security check – introduces a handful of recurring characters, including Smiley’s wife Ann Sercombe, his right-hand man Peter Guillam, Inspector Mendel, and the concept of the Circus department (so-called because it operates out of Cambridge Circus, in London).

Le Carré was still finding his voice, though, and these efforts are still a far cry from later outings. He clearly already knew that he wanted to take a very different path from Ian Fleming’s power fantasies. Lacking Bond’s virile demeanor and glamour, George Smiley is first introduced with this merciless description: ‘Short, fat, and of a quiet disposition, he appeared to spend a lot of money on really bad clothes, which hung about his squat frame like skin on a shrunken toad.’ Yet le Carré wasn’t yet sure what to do with his creation… At this stage, he was heading more in the direction of detective fiction: as the titles suggest, both books involve murder investigations and seem to be setting up Smiley as another quirky sleuth in the long tradition of British mystery literature, his counter-intelligence background serving as a new spin on the Sherlock Holmes/Hercules Poirot type of lead.

A Murder of Quality doesn’t even have much to do with espionage – it’s just an amusing little Agatha Christie-like whodunit set around an English boarding school in the small town of Carne, which serves as a springboard for some pointed social commentary about the British class system (without ever becoming a full-on trenchant satire of the UK’s elite education, a la Tom Sharpe’s Porterhouse Blue). Readable yet forgettable, the book is certainly not mandatory except for die-hard le Carré completists, even if the writing can be quite witty at times:

“Fielding began talking, pontificating rather, with an air of friendly objectivity which he knew Hecht would resent.

‘When I look back on my thirty years at Carne, I realize I have achieved rather less than a road sweeper.’ They were watching him now – ‘I used to regard a road sweeper as a person inferior to myself. Now, I rather doubt it. Something is dirty, he makes it clean, and the state of the world is advanced. But I – what have I done? Entrenched a ruling class which is distinguished by neither talent, culture, nor wit; kept alive for one more generation the distinctions of a dead age.’

Charles Hecht, who had never perfected the art of not listening to Fielding, grew red and fussed at the other end of the table.”

Fortunately, John le Carré soon came into his own with a couple of thrillers that turned the spy genre on its head, 1963’s The Spy Who Came In from the Cold and 1965’s The Looking Glass War. They were set in the same world – George Smiley played small (if crucial) roles in both of them – but operated on a whole other field by providing a bleak yet human glimpse into Cold War intelligence operations. The prose style was also different, with The Spy Who Came In from the Cold written in a much sharper, hardboiled tone, perfectly suited to its gripping, tightly plotted, twist-filled tale of double-crosses revolving around a divided Germany (where the Berlin Wall had recently gone up).

It was a huge leap: The Spy Who Came In from the Cold isn’t just John le Carré’s breakthrough novel, it’s an absolute classic. In turn, The Looking Glass War was an unpopular follow-up, probably because le Carré pushed realism and cynicism to a new level by focusing on an obsolete military intelligence department struggling to remain relevant in the latest political context. Everything about it was imbued with a devastating sense of doom, including descriptions such as this one:

“There are houses which have got the better of their occupants, whom they change at will, and do not change themselves. Furniture vans glide respectfully among them like hearses, discreetly removing the dead and introducing the living. Now and then some tenant will raise his hand, expending pots of paint on the woodwork or labor on the garden, but his efforts no more alter the house than flowers a hospital ward, and the grass will grow its own way, like grass on a grave.”

The Looking Glass War ultimately boils down to an ill-conceived mission carried out by a bunch of pathetic, petty, fallible men driven by misplaced nostalgia in a world that doesn’t really care about them. Me, I love it: this was John le Carré taking genre deconstruction to the extreme, before turning towards reconstruction in the following Smiley novels.

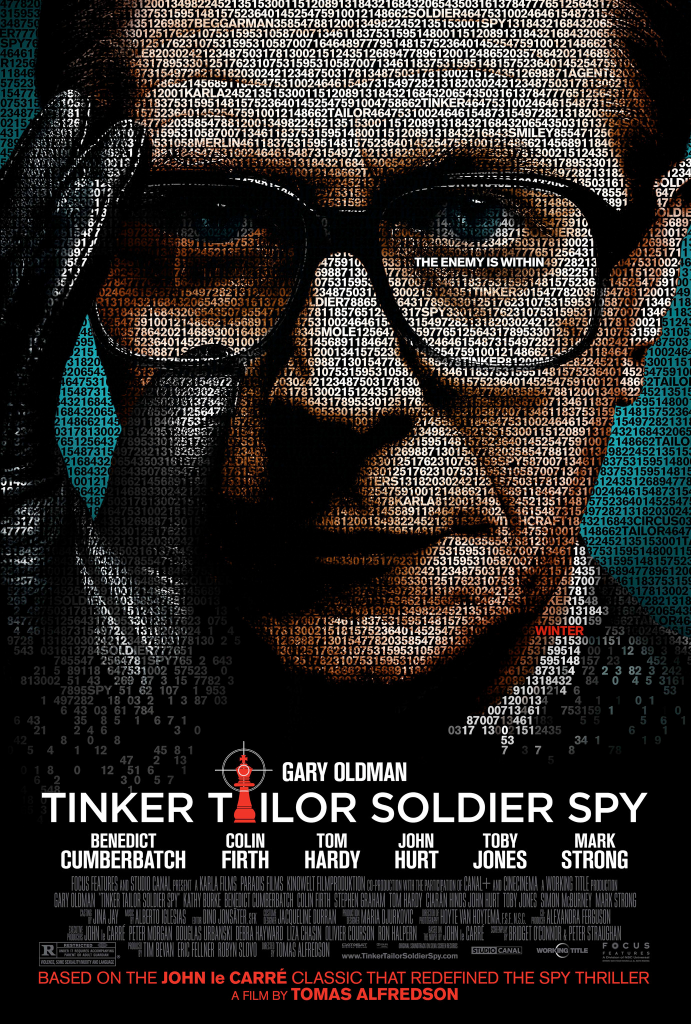

After moving away from the Circus for a couple of books, le Carré came back with a vengeance in 1974’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, his most acclaimed masterpiece. Even though the novel brought George Smiley back to the forefront and it was structured like a mystery, this was no mere throwback: in fact, it told a whole other kind of whodunit, with Smiley hunting a mole at the Circus, clearly inspired by Kim Philby (the real-life double agent who had betrayed John le Carré’s MI6 cover). Above all, le Carré’s writing had matured substantially by then – rather than pushing readers along, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy expects them to attentively and laboriously engage with each character and process (like a true operative would). The book takes a lot of seemingly boring situations, jargon-heavy conversations, and a super-complex plot, told at a glacial pace, and somehow manages to be incredibly absorbing and touching, beautifully merging global and personal stakes.

This book inaugurated a new phase in John le Carré’s body of work, his novels growing in terms of cast, scope, literary ambition, and word count. It was followed by two page-heavy sequels done in the same style – 1977’s The Honorable Schoolboy and 1979’s Smiley’s People – forming the ‘Karla trilogy,’ which revolved around George Smiley’s geopolitical chess games with his Soviet counterpart, Karla. Rather than a one-man show, the series was packed with well-developed figures that often took the spotlight. Notably, self-destructive journalist Jerry Westerby, who had been a supporting character in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, went on to become the protagonist of The Honourable Schoolboy (which was largely set in Hong Kong and war-torn Vietnam). Like the best examples of continuity, these links expand rather than limit readers’ enjoyment… Ultimately, most Circus books can work for themselves, it’s just that they work even better if you read them in order: the twist in The Spy Who Came In from the Cold is even more powerful if you’ve read Call for the Dead beforehand; the revelation of the mole in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is addressed in the books that followed; Smiley’s People’s moving dénouement feels like a kind of inversion of The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, once again set at the Berlin Wall.

The best work I’ve read about John le Carré, Michael Denning’s Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller, points out that reading the Circus novels as a whole one can discern not just an interesting narrative, but also a fascinating ideological development, as the series keeps recontextualizing George Smiley’s position in the grand scheme of things: ‘So behind the similar narrative structures of each book is a kind of narrative across the books, a narrative of ever larger Russian dolls, and of ever smaller and less powerful roles for Smiley. Smiley descends the hierarchy of information from the cold executioner of the Circus, the shadowy figure at the end of the tale who epitomizes absolute bureaucratic knowledge, to the middle-ground hero of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy who embodies a unified knowledge of the fragmented puppets against that of the total organization, and finally, in The Honourable Schoolboy, to a puppet himself.’

Alec Guinness in Smiley’s People

On the big screen, Martin Ritt turned The Spy Who Came In From the Cold into a stylish, suitably downbeat slice of noir in 1965. The following year, Sidney Lumet was less successful with The Deadly Affair – an adaptation of Call for the Dead – which cheapened the source material with more violence and a less subtle approach to George Smiley’s and Ann Sercombe’s couple dynamics (although I’m pretty sure the film inspired a key twist in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, where le Carré took an idea from that adaptation and handled it more elegantly).

On television, the Circus novels’ heavily bureaucratic, politically savvy, counter-Bond take on spy fiction was an obvious inspiration for the awesome show The Sandbaggers. Even the original Mission: Impossible TV series, which – with its fictitious countries, outlandish plots, and minimalistic characterization – sounds like it would fall on the opposite end of the genre’s spectrum, showed a possible influence from le Carré in a few grounded, somber episodes (‘The Reluctant Dragon,’ ‘The Diplomat,’ ‘Nicole’). Another high point was the BBC’s low-key adaptations of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) and Smiley’s People (1982), starring Alec Guinness as George Smiley.

At their best, these films and shows captured the Circus series’ cold, dour mood, yet I still miss the richness of John le Carré’s prose. The truth is that, besides the refreshing pleasure of revisionism and the geeky appeal of intricate continuity, the other reason I enjoy the hell out of these books has to do with the writing. Le Carré is a master of nailing melancholic characterization, fleshing out each cast member into a well-rounded individual. He also has a knack for dialogue, knowing when to play it cool with functional, insinuating exchanges and when to hit you with a powerful line. (‘Do you know what love is? I’ll tell you: it is whatever you can still betray.’)

That said, from the point of view of identity politics, I should point out that the cast is not very diverse, even if the series came to include increasingly nuanced portrayals of homosexuality over the years. Among the few female characters who stand out, my favorites are the recurring alcoholic Russian analyst Connie Sachs, A Murder of Quality’s Ailsa Brimley (who has a touch of Miss Marple), and Maria Andreyevna Ostrakova, the Soviet émigré in Paris who kickstarts the events of Smiley’s People.

As the Cold War drew to an end, John le Carré did a trio of novels that further expanded his universe while also playing around with form, continuously stretching his writing muscles. 1989’s The Russia House was the first book of the lot with a first-person narrator, namely Harry Palfrey, a legal adviser to the British secret services. It’s a wonderful read, with a fact-checking operation serving as a pretext to engage with the Perestroika-era USSR in a tale that is at once political and romantic. Initially, it may not seem like it belongs in the Circus series, but one of the supporting characters, Ned, then shows up as the narrator of 1990’s The Secret Pilgrim, which resembles an essay anthology framed around a set of lectures by George Smiley. In turn, Palfrey reappears (in a secondary role) in 1993’s The Night Manager, le Carré’s first proper post-Cold War entry and the closest he has come to a ‘boys’ own’ adventure yarn.

While I’m not a big fan of the clichéd The Night Manager, I can’t sing enough praise about The Secret Pilgrim, which could’ve been a perfect coda to the Circus series (and to the Cold War itself). It is also the main exception to what I said about the books mostly working as self-contained works – The Secret Pilgrim is certainly not the best place to start right away, as it’s full of spoilers about the other Circus installments (as well as Russia House) and it hits you harder the more familiar you are with George Smiley. That said, it’s a brilliant book with some of the best spy short stories ever written this side of Jorge Luis Borges’ ‘The Garden of Forking Paths.’ It’s certainly worth reading after you’ve checked out at least a couple of le Carré’s previous novels.

As for John le Carré’s subsequent output, it belongs to a whole new phase, consisting of unrelated standalone thrillers that tend to be less ideologically complex, denouncing imperialism in a (comparatively) more straightforward way. They’re not bad, but they do pack less of a punch than the Circus novels. For one thing, the characters (even the most psychologically rich ones) are not as memorable, except perhaps for the charismatic protagonists of The Tailor of Panama and The Mission Song.

Meanwhile, most adaptations have been instantly forgettable, with the honorable exception of Tomas Alfredson’s film Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), which edited down John le Carré’s story into a visual puzzle that works as quite an eccentric piece in its own right. (Honestly, despite focusing on American gangsters rather than British spies, the closest thing to a screen version of le Carré’s signature blend of high politics and intimate drama, with an intricate, languidly told tale full of seasoned professionals talking in tradecraft-informed shorthand, was last year’s The Irishman, by Martin Scorsese.)

Finally, in 2017 John le Carré delivered a 21st century epilogue to the Circus series with A Legacy of Spies, his best novel in over a decade. If le Carré’s Cold War phase was mostly about the ambiguity of the oppressors and the later stuff about empathy with the oppressed, A Legacy of Spies intelligently combined the two perspectives in the form of a parliamentary enquiry into the sacrificed pawns of the Cold War… And not just any pawns: precisely the ones le Carré had written about early on, as the current-day investigation allowed us to visit the background of The Spy Who Came In From the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, thus making the book simultaneously a sequel and a prequel to those novels (even if the guilt-ridden Peter Guillam makes for an unreliable narrator).

Unlike most prequels, which basically fill in unnecessary backstory and often cheapen the original work, A Legacy of Spies actually illuminates and interrogates the other stories. It’s not a shameless nostalgia trip – in fact, the book manages to be quite topical, dealing with our collective memory of the Cold War against the background of the War on Terror, not to mention the Brexit zeitgeist. It’s also one hell of a read: it includes one of the tensest escape sequences from the GDR I’ve ever come across and, because a lot of it is told through official reports, you have to keep reading between the lines and decipher what is not being said.

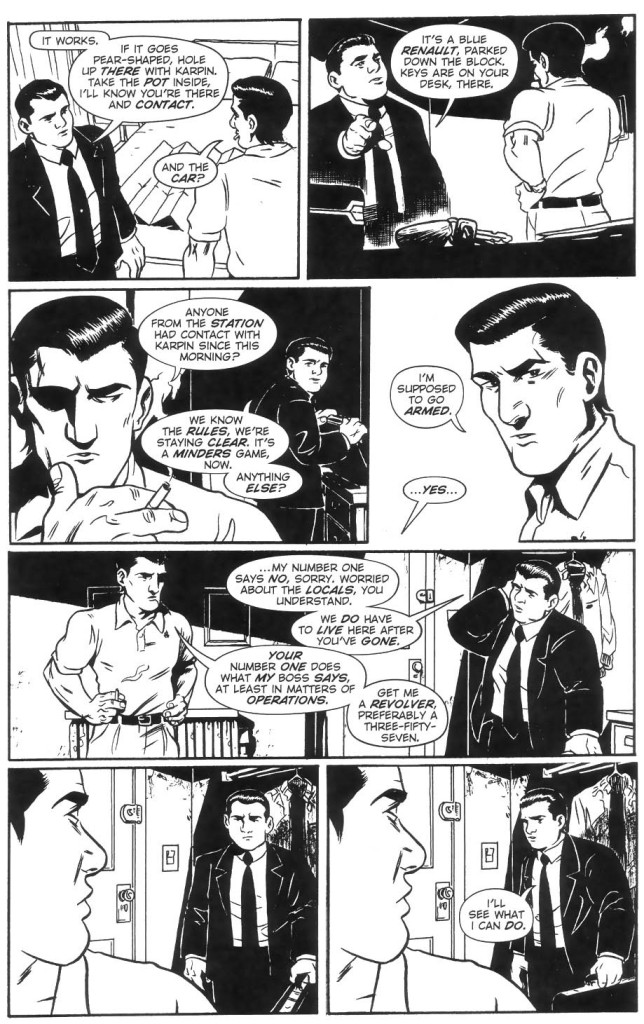

In comics, nothing quite compares to the dense texture of John le Carré’s work. Nevertheless, some creators have pleasingly sought to emulate his grounded approach to the genre, most notably Antony Johnston in the Coldest City/Coldest Winter graphic novels (whose tone has absolutely nothing to do with the campy film adaptation, Atomic Blonde) and Greg Rucka in the Queen & Country series, which even includes a three-issue spin-off set during the Cold War:

Queen & Country: Declassified #2

Queen & Country: Declassified #2

So, assuming I’ve convinced you to give the Circus series a try, what are the obligatory reads? The first novel, Call for the Dead, is the obvious starting point for completists, but if you just want a quick sample of John le Carré’s talent, then I recommend going with The Spy Who Came In From the Cold: it’s one of the most influential books in the whole genre and it works really well on its own (in other words, the plot doesn’t require you to be familiar with Smiley’s previous adventures, it’s just that those who’ve read Call for the Dead will get a special kick out of what happens to a certain supporting character). Or you can jump straight into le Carré’s magnum opus: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, which is more demanding (yet rewarding) than its predecessors, but it doesn’t expect you to have read what came before. Choose any of these and let yourself get lost in the meanders of British espionage. Spy yarns will never feel the same again.