John Ostrander has written more cool comics than most of his peers. Some of them feature Batman and other Gotham citizens, although those projects don’t always play to his strengths, since they tend to be short fill-ins or mini-series. Ostrander is usually at his best when doing long runs that allow him to redefine characters and show them growing through an evolving status quo, like he did with GrimJack, Firestorm, Hawkman, Martian Manhunter, and the Spectre. Nevertheless, overall Batman comics have been quite well served by Ostrander’s talent for expanding franchises in imaginative ways.

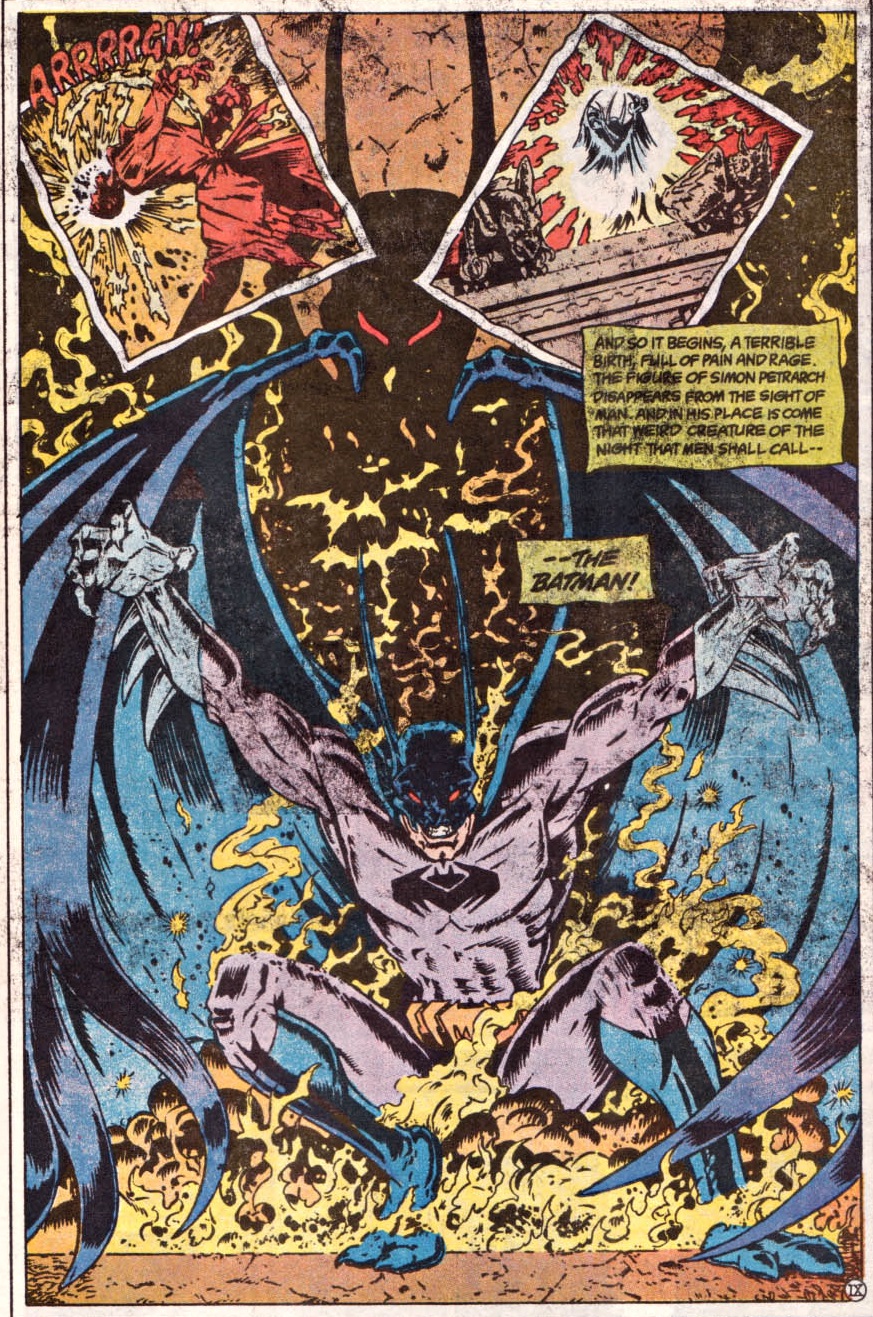

Before looking at his Batman-related work, let us consider what makes Ostrander such an engaging writer. Basically, he is a fabulous storyteller with a knack for world-building, sharp characterization, and forward momentum. His prose may not be as literary as, say, that of Alan Moore or Neil Gaiman – what with the occasional heavy-handed exposition and clunky dialogue – but he’s a master at exploring the implications of the characters’ more fantastical aspects and pitting them against each other in confrontations that reflect a broader clash of worldviews. And while Ostrander can do gritty realism when he feels like it, he can definitely do weirdness just as well:

GrimJack: Killer Instinct #3

GrimJack: Killer Instinct #3

In short, John Ostrander knows how to tap into the potential of existing concepts and build on them. He’s ultimately an old-school pulp author, in the best possible sense – reading his stuff often reminds me of why I fell in love with comic books in the first place. The reason for this is the fact that, although he sometimes weaves in darker subject matter, Ostrander is not ashamed of embracing even the goofiest source material and make the most out of what is there. In the case of superheroes, this means taking the genre’s most preposterous tropes (from the campy names and costumes to the operatic battles and outlandish twists) and just running with it.

You can see all this in Ostrander’s first work for DC, the 1986 company-wide event Legends. The premise of this crossover is that the sinister Darkseid convinces people to distrust the value of superheroes, including their simpleminded morality and questionable lawfulness. In a revealing turn, however, Darkseid isn’t able to persuade the children, who are pure of heart and, therefore, know that superheroes are cool. And John Ostrander damn well knows it as well!

Not that Ostranser’s works can be dismissed as childish. In fact, they often display adult sensibilities, drawing on current affairs, typically in the form of comics-à-clef (for example, The Spectre featured ill-disguised versions of O.J. Simpson and Kurt Cobain). Perhaps because of his background in Chicago’s Organic Theater Company, Ostrander has also proven apt at satire, whether in his black comedy anthology Wasteland (no, not that one) or in the amusing, Producers-style take on elections he did for GrimJack #8.

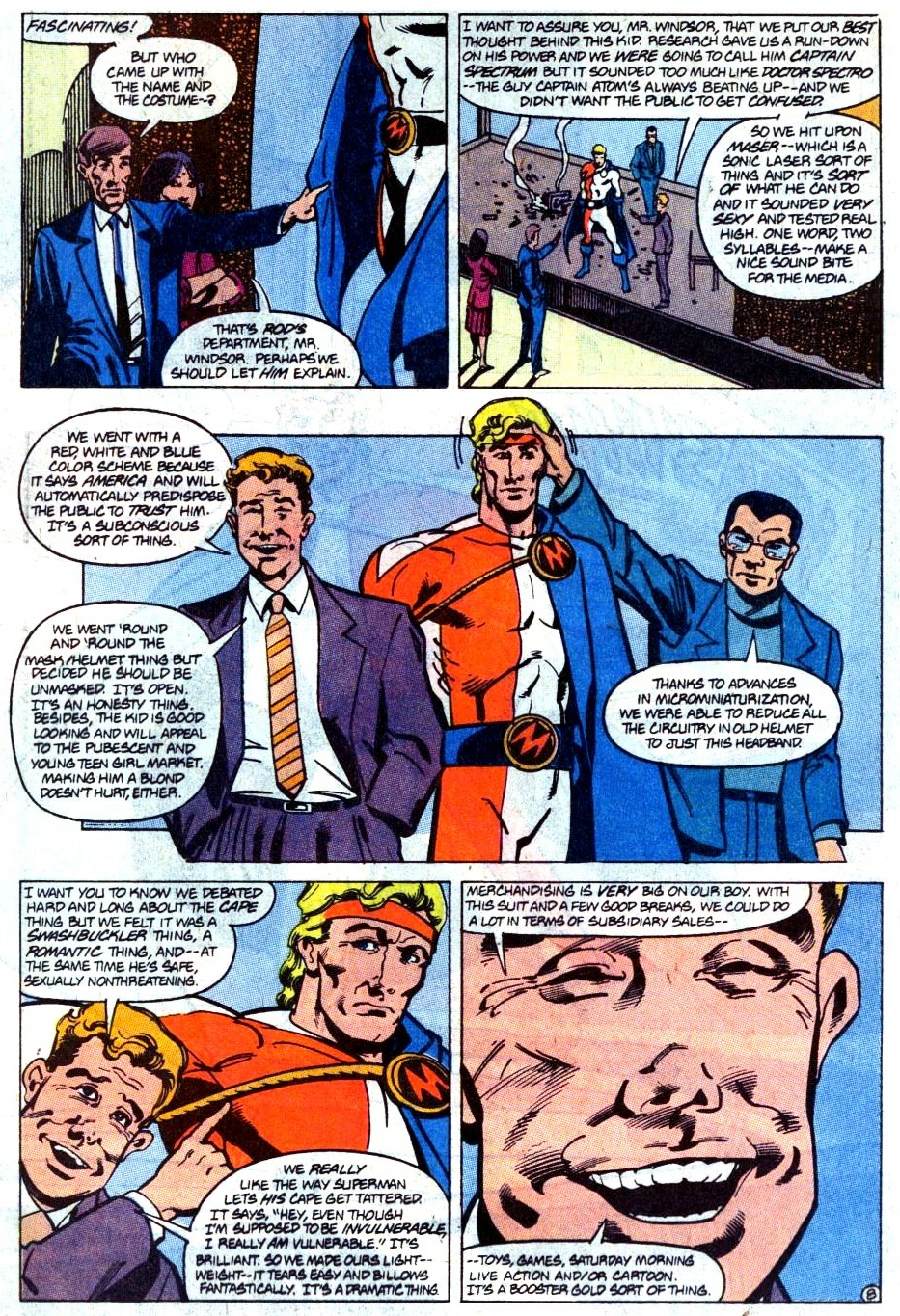

I still get a kick out of one of the subplots running across his DC series of the late ’80s, in which big corporations sought to develop their own brand of superheroes, called Captains of Industry:

Firestorm, the Nuclear Man #88

Firestorm, the Nuclear Man #88

So yeah, John Ostrander can be awesome. But does his Batman work live up to this? Well, not all of it…

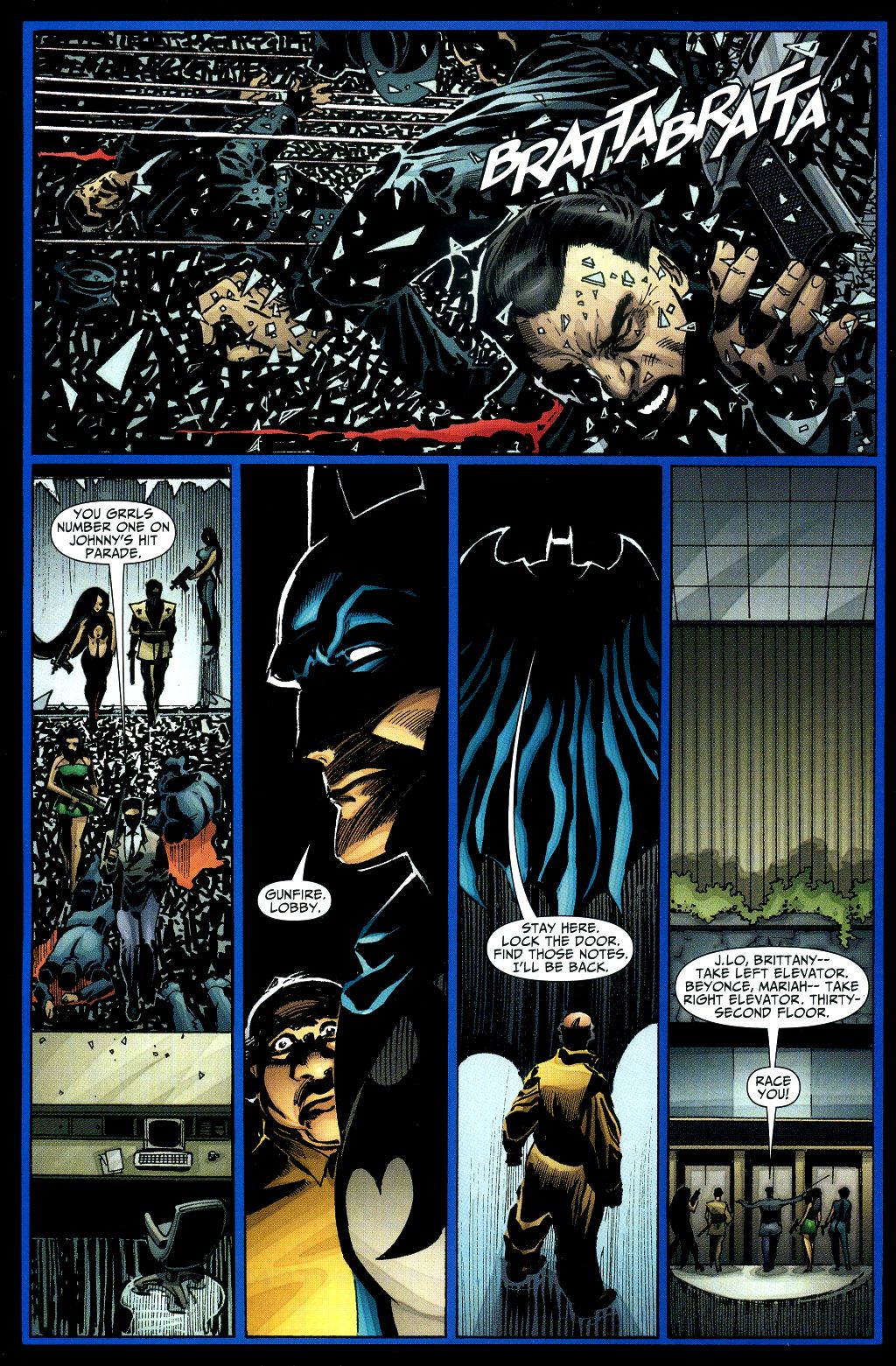

In an attempt to capitalize on Tim Burton’s Batman Returns, in 1992 DC released a couple of specials about the film’s villains. While Catwoman: Defiant is an unsung gem, Ostrander’s Penguin: Triumphant is bafflingly silly – it involves the Penguin going legit and moving into Wayne Manor, which could’ve worked as a sort of homage to the Silver Age, but instead it just comes across as dumb and contrived. ‘Lost Boys’ (Batman Annual #24) is a ghost story in England that somehow manages to be utterly uninteresting. Just as instantly forgettable, the fill-in arc ‘Grotesk’ (Batman #659-662) feels like a mercenary rehash of boring clichés, despite a quirky heist attempt by a Japanese singing gangster called Johnny Karaoke and his armed geishas…

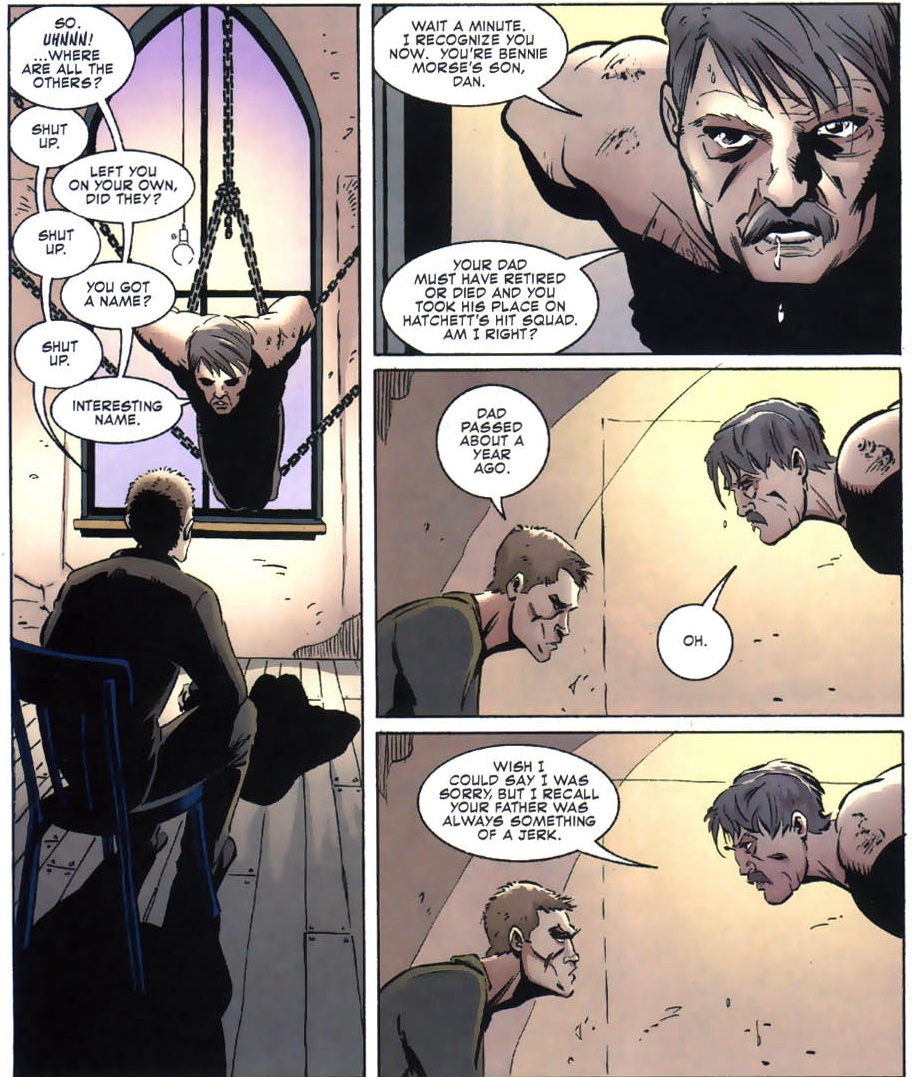

Batman #660

Batman #660

Moreover, John Ostrander wrote a pretty lame Catwoman arc during the No Man’s Land crossover. If that one has any redeeming feature, it’s the Tarantinoesque interactions between henchmen who are used to viewing big events from the sidelines…

Catwoman (v2) #72

Catwoman (v2) #72

(The next line is even more meta: ‘Prison shrink I had, doc by the name of Wertham, he always claimed the bat was a freakin’ weirdo an’ he just get a new Robin when one got too freaking old.’)

Fortunately, it isn’t all bad. Like I said, Ostrander tends to push forward whatever properties he touches. He enjoys playing with other people’s toys, frequently participating in crossovers, delving into older stories, reviving (and reinventing) forgotten concepts, tweaking continuity, and tying up other creators’ loose threads – in his comics, you can find, for example, a surprising follow-up to the epic finale of Grant Morrison’s Animal Man run (in Suicide Squad #58) and amusing throwbacks to the Justice League’s comedic era (Martian Manhunter #24, JLA: Incarnations #6). Moreover, nobody can accuse Ostrander of not contributing with plenty of toys of his own, having deeply enriched the DC, Marvel, and Valiant universes, not to mention the world of Star Wars.

Granted, his creations aren’t always successful, but there is such gusto in the way he keeps throwing new characters at the readers, often with an eye towards diversity, like in the cases of the gay barbarian Suu of Xoo, the African-American genius Mr. Terrific, and the Soviet half of Firestorm’s dual identity, Mikhail Arkadin (complete with a remarkably fleshed out Russian family). Notably, Ostrander has been responsible for populating the DCU with all sorts of regular people that are as interesting to read about as the superheroes, such as the psychiatrist Simon LaGrieve, the priest Richard Craemer, and the overweight White House hawk Amanda Waller, whose original version remains hands-down one of the most gripping black female characters in the history of mainstream comics.

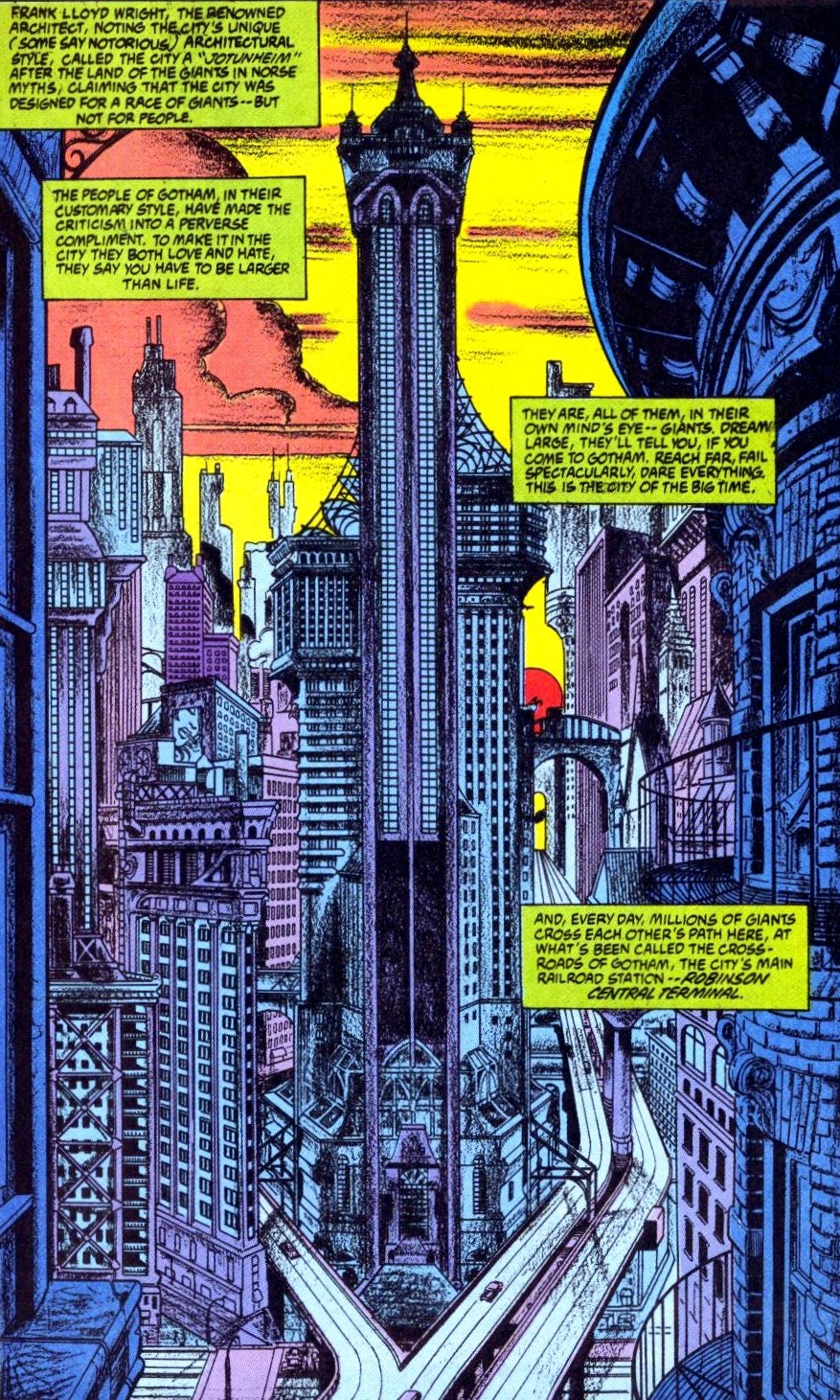

Along this line, Ostrander’s humanist touch and his flair for world-building led him to expand our perception of Gotham’s civilians and the everyday life of the city (one of my favorite topics). He did this through two Gotham Nights mini-series, elegantly illustrated by Mary Mitchell, that refreshingly moved the spotlight away from the Caped Crusader and his rogues’ gallery, focusing instead on the dreams and dramas of average Gothamites (most of whom aren’t psychopathic killers). The first mini, published in 1992, beautifully explored the city’s identity through interconnected street-level vignettes as well as through inspired musings at the beginning of each issue:

Gotham Nights #1

Gotham Nights #1

The second series, which came out three years later, is more plot-centric, even if it also features its fair share of Eisneresque melodrama. Gotham Nights II takes place at the Charles Paris Amusement Park (probably named after the classic Batman artist and inker), better known to Gothamites as ‘Little Paris,’ and it evolves into a whodunit about someone trying to kill the amusement park itself.

This wonderful comic shows John Ostrander’s continued interest in the non-powered, non-costumed inhabitants of superhero universes, coming up with a whole new cast (so you don’t need to have read the previous mini to appreciate this one). Notably, Gotham Nights II introduces the artistic neighborhood of Little Bohemia, home of eccentric sculptor Francesco Xavier, who almost feels like a Peter Milligan creation… Xavier and his two groupies get all the best lines in the comic:

Gotham Nights II #2

Gotham Nights II #2

Some of John Ostrander’s more Batman-centered work is equally praiseworthy, benefitting as it does from the fact that the man knows how to pen a damn crime yarn. Ostrander is one of those hardboiled liberals who gets a kick out of writing macho characters and slangy dialogue (plus, he’s arguably the king of badass one-liners). These traits are on full display in Detective Comics #622-624 (cover-dated October-December 1990), in which the Dark Knight investigates a serial killer who’s chopping up people with a machete and signing the crime scenes as ‘Batman.’

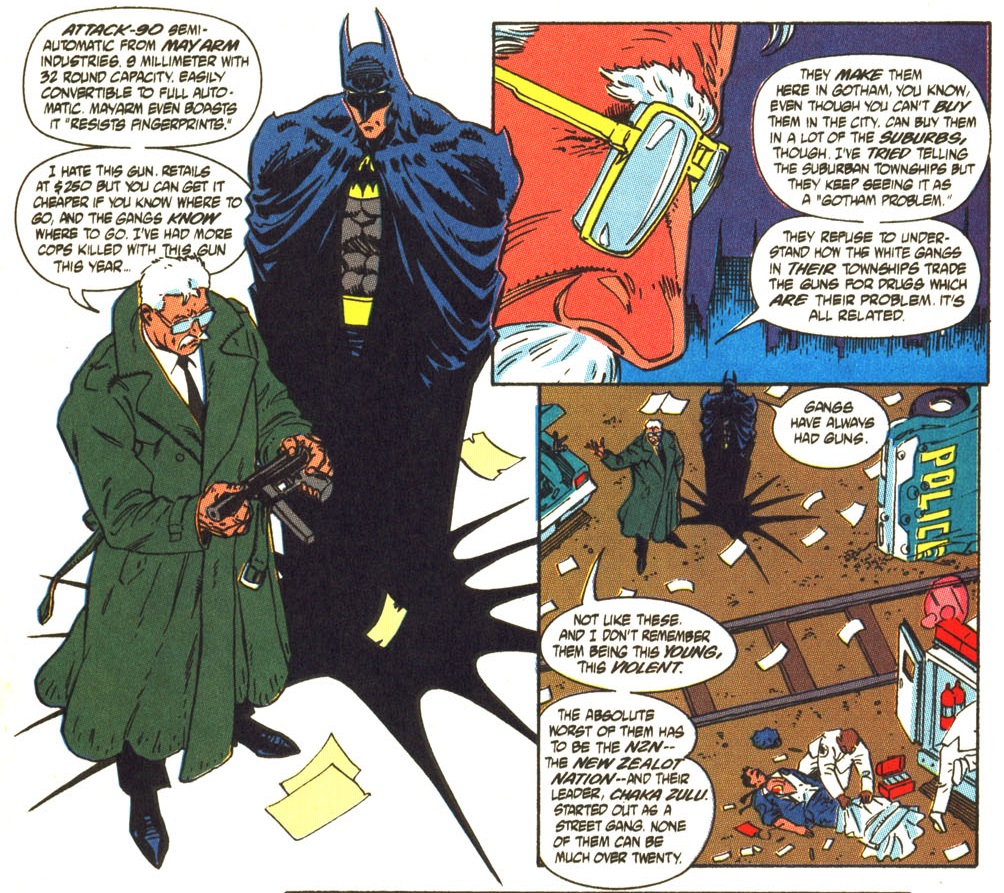

Ostrander’s crime genre credentials were mobilized for a different purpose a few years later. After the shooting of John Reisenbach, the son of Warner Brothers’ longtime marketing executive, DC’s editor-in-chief Jenette Kahn and vice-president Paul Levitz commissioned a benefit comic that, according to its backmatter, ‘would indict the proliferation of guns in this country and the ease with which they are used.’ Batman editor Denny O’Neil offered the job to Ostrander, who had once worked with an anti-gun organization. (You can read more about his views here.)

The ensuing one-shot, Seduction of the Gun, was published in 1993. While the militant agenda means that the comic does get a bit preachy at times (with people spouting detailed information about fire arms, legislation, and gun violence statistics), Seduction of the Gun is still a pretty solid crime story, stylishly illustrated by Vince Giarrano.

Seduction of the Gun

Seduction of the Gun

This should be no surprise: after all, like Alan Grant and Doug Moench (two other writers working on Batman comics at the time), John Ostrander had never shied away from hot political topics: his groundbreaking run in Suicide Squad was always on the cusp of international crises, Hawkworld was about a couple of (literal) aliens learning how to deal with the US system, the protagonist of Firestorm tried to stop the nuclear arms race and end African famine… Hell, just the previous year, Ostrander had been behind a provocative special issue of Blackhawk dealing with conspiracy theories! So, yes, Ostrander knew how to tell a tale that was both political and engaging, which is what he did in Seduction of the Gun: Batman gets a lot of badass moments as he goes up against street gangs and gun dealers, but this is no simple wish-fulfilment fantasy – the book brutally drives home the point that guns have consequences and no one is entirely safe from them.

With a similar gritty vibe, in the early 2000s Ostrander penned ‘Snap’ (Gotham Knights #43), a black & white short story about Batman’s urban legend status, as well as the taut thriller ‘Loyalties’ (Legends of the Dark Knight #159-161), set early in Batman’s career, when Jim Gordon’s Chicago past came back to haunt him…

Legends of the Dark Knight #160

Legends of the Dark Knight #160

‘Loyalties’ delivers not only plenty of action, with Batman engaging in a kickass motorcycle race through the streets of Chicago (where Ostrander is from), but also great character moments all around, as everyone’s loyalties are put to the test – and some break down, while others don’t. In particular, this three-parter works as a nice (retroactive) introduction to pre-Batgirl Barbara Gordon, a character that Ostrander has crucially fleshed out over the years.

John Ostrander’s history with Barbara Gordon brings me to another point. His greatest contributions to the Batman mythos involved taking existing characters and imbuing them with extra depth, as well as with a life beyond the shadow of the Caped Crusader, usually on the pages of his magnum opus: Suicide Squad. This is where Ostrander, together with his wife Kim Yale, turned the former Batgirl – who had been cruelly crippled in The Killing Joke – into the super-hacker Oracle (a transformation they later revisited in Batman Chronicles #5). Coming to terms with her disability, Barbara excelled at this role throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, when Oracle was one of my favorite DC characters. Along with Babs, all sorts of familiar faces who had passed through Batman comics – such as Bronze Tiger and Katana – found a new breath of life in Suicide Squad. Notably, Ostrander turned Deadshot from a superficial Batman villain into a genuinely complex and fascinating anti-hero (Ostrander further developed Deadshot’s background in a nifty 1988 mini-series, again co-written with Kim Yale).

Other rogues – from the Penguin to Poison Ivy – were given a chance to shine in Suicide Squad while undertaking ambiguous secret assignments for Washington, led by the conflicted Rick Flag. What made this series work so well was that the villains kept their personalities even as they were recontextualized as the protagonists – mixing The Dirty Dozen with the Iran-Contra zeitgeist, this was a gleefully cynical comic about fucked up black ops agents who hated each other and mostly moved in morally dubious areas of international politics. This is why my main frustration with the recent Suicide Squad movie wasn’t just that it was an ugly, largely incoherent mess, but also the fact that it ultimately turned into a story of friends-who-are-good-at-heart on a mission to save the world from purely evil supernatural forces (even the despicable Captain Boomerang ultimately has a change of heart and comes back to save the day, for some reason), thus missing what I most like about the comic.

The Dark Knight himself made some appearances on the pages of Suicide Squad, including memorable confrontations with Amanda Waller and Rick Flag. This is the other way in which Ostrander expanded Batman’s world – he powerfully connected Bats to the wider DCU by strengthening the ties between the Caped Crusader and other properties. Batman investigated Superman for murder (JLA 80-Page Giant #1) and played a key role in various Justice League adventures (like in the masterful JLA: Incarnations mini-series and in the fun Justice League Adventures #21, as well as in the sadly uninspired JLA Versus Predator). Hell, Batman even helped save Washington from an ape coup:

JLA: Incarnations #2

JLA: Incarnations #2

Ostrander and his regular collaborator Tom Mandrake also had the Dark Knight cross paths with the titular leads of their runs in The Spectre and Martian Manhunter. The former included a brilliant Joker tale, titled ‘A Savage Innocence,’ that tied into the series’ running theological themes by having Batman argue with the Spectre over whether or not the Clown Prince of Crime could actually be considered evil and accountable for his actions, since he was obviously insane, unable to distinguish right from wrong.

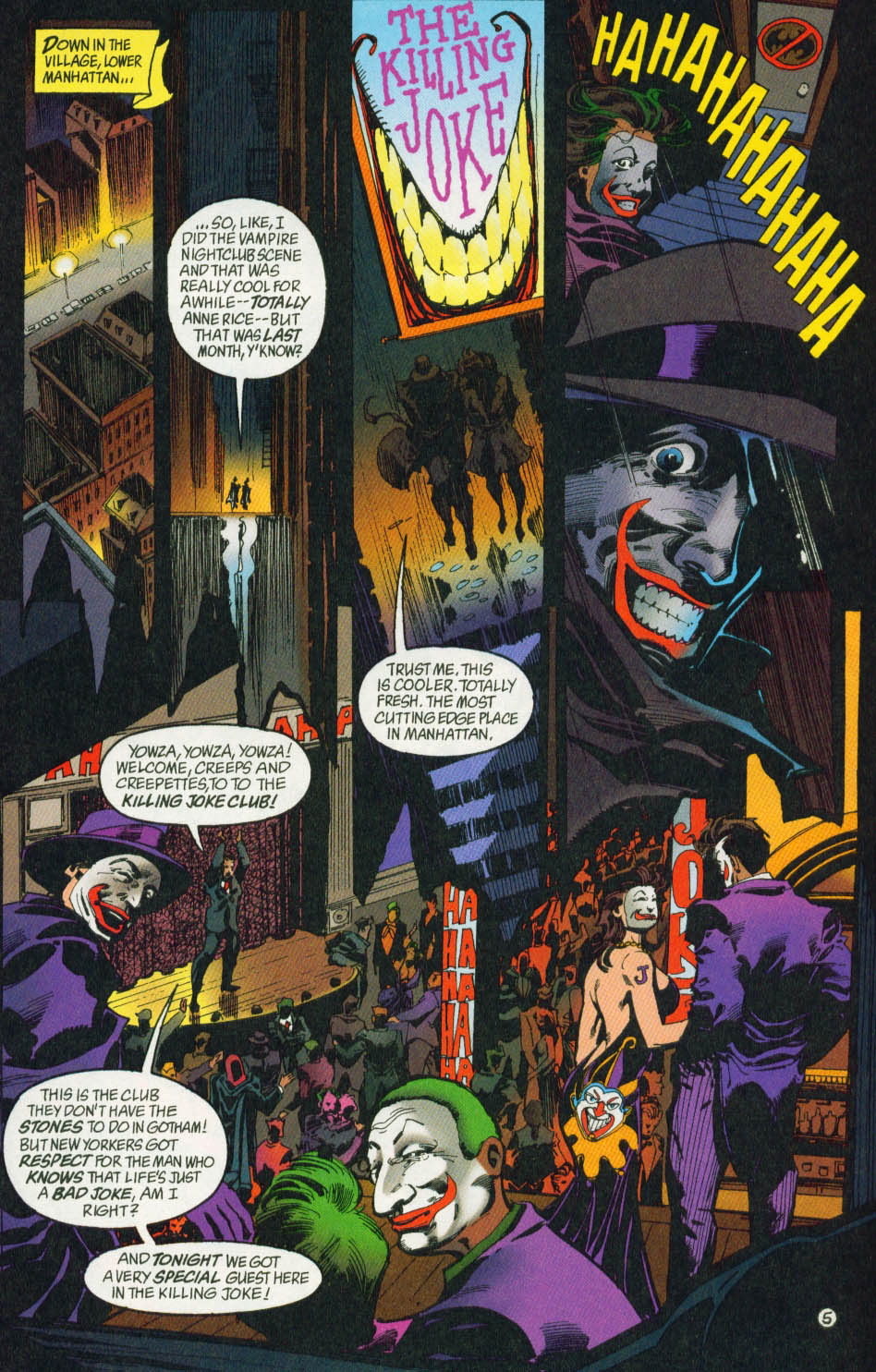

As a bonus, the issue showed us how the Joker’s reputation had affected the New York club scene:

The Spectre (v3) #51

The Spectre (v3) #51

This notion that costumed heroes and villains must have a wider cultural impact in their own world is something I find infinitely appealing. John Ostrander had already touched on it in the aforementioned Detective Comics #622-624. There, besides the neat detective story, we got a fun journey into metafiction, since the mystery tied into a comic-within-the-comic about the Dark Knight (because Batman is not trademarked in the DCU). The joke, of course, is that those comics would display a distorted image of the Dynamic Duo and the rogues’ gallery, envisioned by someone who had never actually met them for real. The sample pages, drawn by Flint Henry, are freaking out there…

Detective Comics #622

Detective Comics #622

Thus, although unfortunately John Ostrander was never given a long run in Batman comics – one where he could do for the Caped Crusader what he did for many other heroes – he has still managed to expand their scope, making readers feel like the Dark Knight is part of a larger universe out there, full of complicated characters living their own interesting sagas.