Last week I went to see Dune: Part Two, Denis Villeneuve’s epic about Afghanistan on an alien planet, which overcomes *some* of my reservations about the previous film. While the screen is once again filled with masses of anonymous blind followers/NPCs treated as mere cannon fodder by both their leaders and the filmmakers, we do get to finally meet a few non-elite people who eat and laugh and do things besides spouting ponderous bullshit about prophecies and bloodlines (although they do a lot of that, too). As far as sound and visuals go, the movie offers an impressive and immersive experience, with the focus largely shifting from imperial intrigue to the desert guerrilla, including some very exciting battles.

That said, the whole thing does come across like a slow-burn version of The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire…

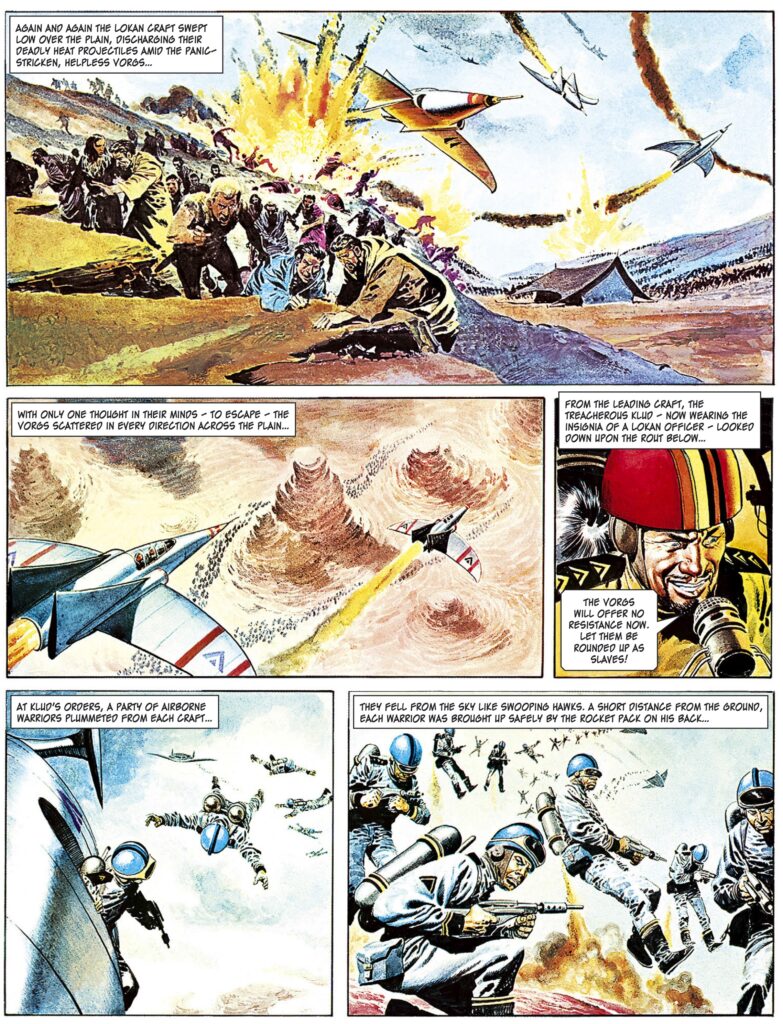

The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire: Volume 1

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve been having a blast reading the thick volumes collecting this saga, originally published in the UK in the 1960s and ‘70s. Like with Dune, much of the appeal derives from the stunning images, as the luscious painted artwork combines photorealistic pencils with psychedelic coloring. The stories aren’t very elaborated, although they do have a cumulative effect, gradually chronicling the development of a Roman-style empire on a distant planet, starting from a small tribe and building up to an interplanetary enterprise.

The series was originally published in very short installments (often just a couple of pages), so it moves at a frantic pace and the narration does plenty of heavy-lifting in terms of pushing the story forward, but even that works for me: it reads like those old legends where you get the gist of a story with varying degrees of detail, which further reinforces the feel of an epic passed down through generations… It’s like fast-forwarding through Games of Thrones, but with less sex and more spaceships.

Presumably there is some peace and prosperity between adventures, but by binge-reading these comics you get the impression that not a month goes by without the rulers getting manipulated by enemies or possessed by evil aliens. All we see is constant turmoil, with so many wars and invasions – not to mention so much back-stabbing and mind-control – that it’s a wonder the empire doesn’t immediately collapse, its masses either resentful or at least utterly confused by the elites’ erratic behavior.

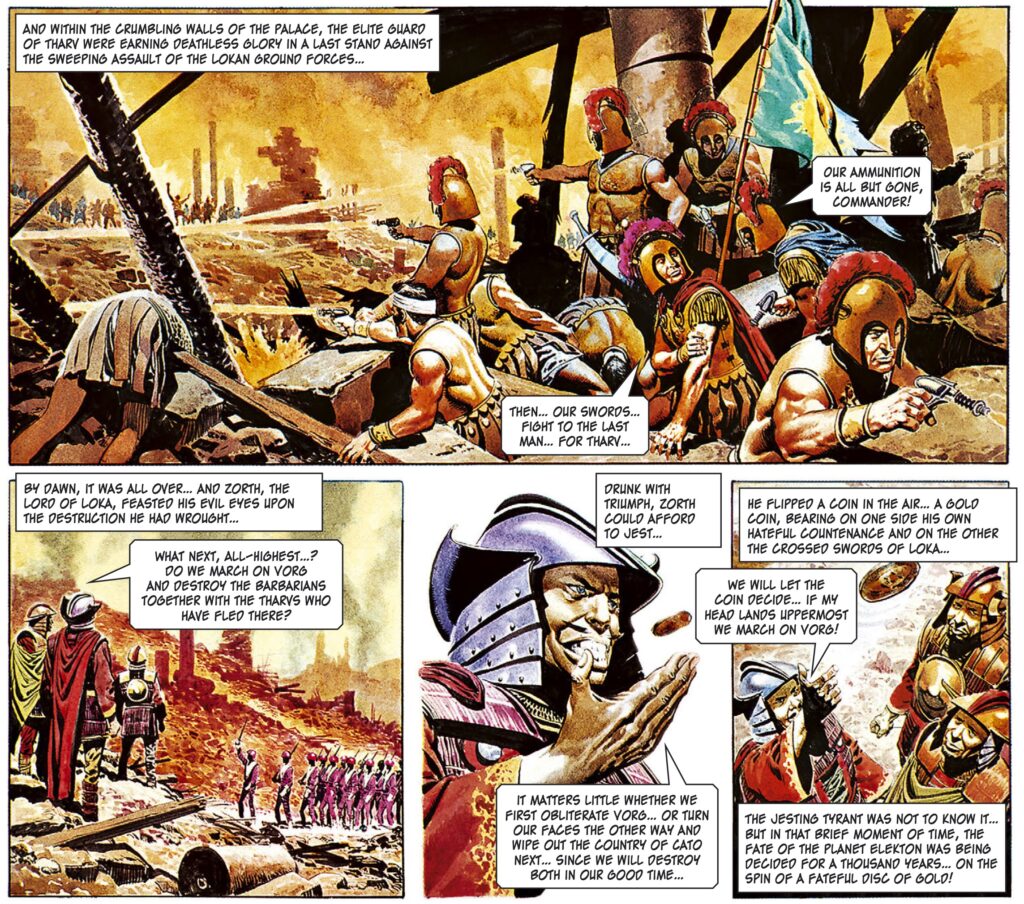

The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire: Volume 1

Given the imperial dimension, it shouldn’t surprise that this subgenre was so popular among British comics, whose Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future originally resembled an aspirational bastion of Englishness before becoming more of a cartoony parody in the likes of Peter Milligan’s 2017 mini-series (whose collection is cleverly titled He Who Dares, thus underscoring the military angle).

And just as yarns about space empires tend to fictionalize forms of colonialism and neo-colonialism, interplanetary war tales often turn into texts about anti-imperialist resistance. This is sometimes disguised by all the fantasy and, in the best cases, by original characterization that rises beyond mere allegory, but it’s such a blatant theme in most stories that you can hardly call it subtext. Still, there are very different ways of approaching this type of material (from the lighthearted thrills of The Midas Flesh to the metafictional satire of Six-Gun Gorilla, to highlight a few), each with their own implications.

If you want to find a pure treatment of the subject, look no further than the late 1970s, when British comics tended to be raw-as-hell and in-yer-face, so there was little ambiguity (or nuance) about the overall point…

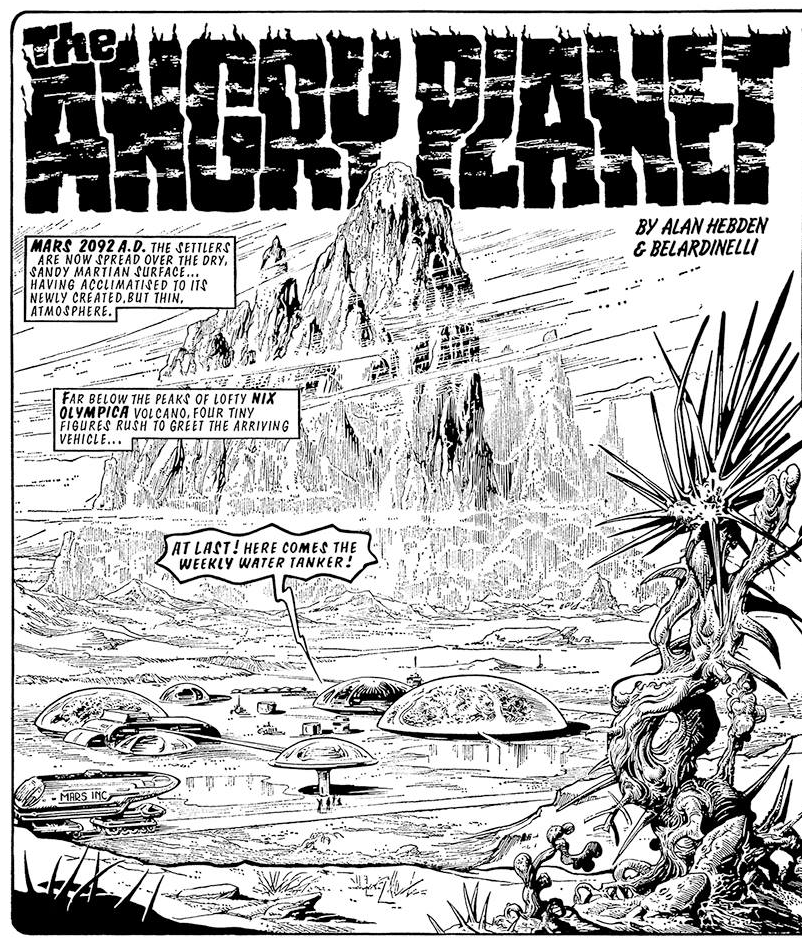

Tornado #1

Take, for example, The Angry Planet – originally published in the anthology Tornado and collected a few years ago by Rebellion and Hibernia – in which Earth’s relationship with Mars in 2092 is an obvious stand-in for the First World’s relationship with the Global South in the late 20th century. The main villain is a capitalist corporation – Mars Inc. – which mercilessly exploits the red planet’s resources while keeping the local population (i.e. Martian-born humans) in check through its monopoly of the water supply… until one of the farmers, Matt Markham, gets fed up with the whole thing and kickstarts an independentist armed struggle, his guerrillas compensating for the asymmetrical weaponry through creativity and their greater familiarity with the territory.

The series was written by Alan Hebden, a specialist in action-packed war comics (like Death Squad and Fighting Mann), and he seems to have simply transposed his research notes about Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara onto outer space. Since Hedben is more about bombastic cliff-hangers than psychological character development, the result is fascinatingly straightforward: you are left with a very surface-level metaphor, albeit peppered with the typical gonzo style of the era’s genre comics, including a tyrannical security chief called The Samurai and a pack of killer robot dogs called Dogroids. (In any case, if nothing else, Angry Planet would be worth it just for Massimo Belardinelli’s fabulous artwork, which instills every set piece with breathtaking visual wonder.)

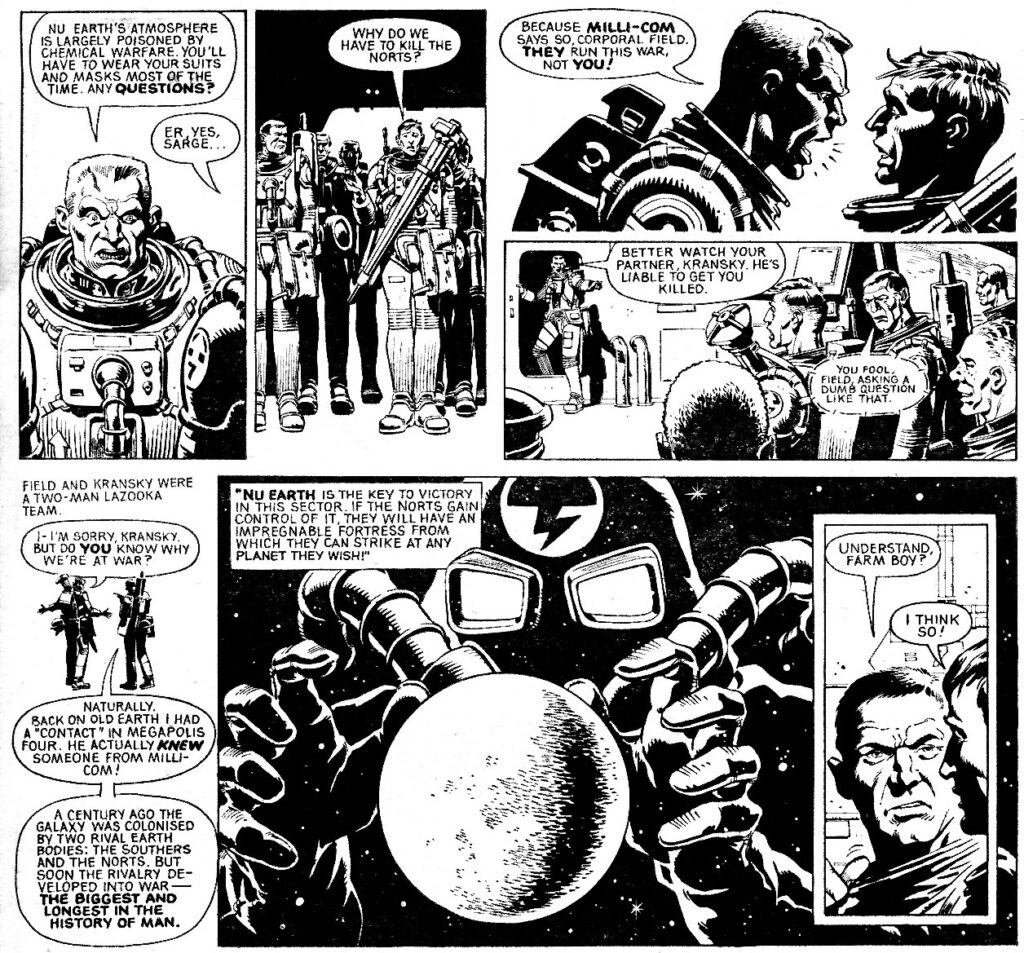

Soon after, another British comic proposed a more cynical take on the genre. Created by Gerry Finley-Day and Dave Gibbons, the original Rogue Trooper (serialized in 2000 AD in the ‘80s) followed a war of attrition between two human factions – the Southers and the Norts – on the planet Nu-Earth. The series loosely echoed different real-world conflicts and, on the whole, the Norts were more unabashedly despicable (which suggests a classic anti-imperialist indictment of the Global North), but the point was clearly that, at the end of the day, this was a war between imperialisms, where the main loser was the little guy (bear in mind that by the time the series entered its second year the UK was embroiled in a new conflict, the Falklands War).

2000 AD #239

That said, overall Rogue Trooper was more interested in warfare as entertainment than in any kind of direct analogy. Yes, its chemically devastated battlefield was a powerful post-apocalyptic vision and there were occasional statements about war, but the metaphors kept shifting from episode to episode. Combat action beats were intercut with 2000 AD’s propensity for surreal comedy and silly puns, including Nort poisoners infiltrated behind Souther lines, cheekily labelled ‘filth columnists,’ and a demented resistance cell with outrageous French accents that called itself the Napoleonic Complex (and which named a theater after the series’ protagonist: Moulin Rogue).

On the big screen, the approaches don’t tend to be either as ferociously revolutionary or as wildly iconoclastic, although Star Wars has notably gotten away with plenty of weirdness. That franchise has always had a political edge, whether it was A New Hope responding to the Vietnam War (with the Empire cast as the villain and the rebels as heroes) or Revenge of the Sith evoking the War on Terror (with Darth Vader paraphrasing George W. Bush as the democratic Republic turned to tyranny). Personally, I’m fond of the attempts to frame the conflict from a more street-level perspective, like in Rogue One and Solo – both those movies were pretty uneven (no doubt because of director/producer clashes) and featured some eye-rolling fan-pandering, but I dig how they fleshed out this galaxy from a lumpen POV. And then, of course, came the show Andor, which got it right at almost every turn, zooming in on the mixed feelings of the colonized as well as on the petty bureaucratic disputes of the fascist system.

That focus on the grunts fighting on the ground and not just on their leaders is what elevates some the coolest military science fiction in my book, even allowing it to get away with the complete dehumanization of extraterrestrial enemies, as in Aliens or Edge of Tomorrow. The former, by the way, immediately inspired a number of awesome comics.

Aliens: Nightmare Asylum

By contrast, Dune feels more like a throwback to The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire, with its earnest tone and macrolevel point of view. Surely, there is something provocative about the way Villeneuve’s films gear up viewers with a righteous liberation struggle against colonial oppression and exploitation while simultaneously dramatizing the tragic rise of warmongering religious fundamentalism, but I can’t quite decide whether the somber, straight-faced orientalist imagery ironically reinforces or undercuts the effect. On the one hand, you’d think the timing is right to complicate easy narratives about Ukraine or Palestine. On the other hand, the whole thing is still too clean, shying away from dealing with civilian casualties or from humanizing combatants (the latest film takes great advantage of the desert setting, as most fighters wear face masks, so we don’t witness their suffering or possibly conflicted emotions…). We’re invited to see them as generals do: disposable pawns in a larger game. In that sense, this Dune depressingly feels much in tune with the current acceptance of atrocities in the name of fantastical myths.