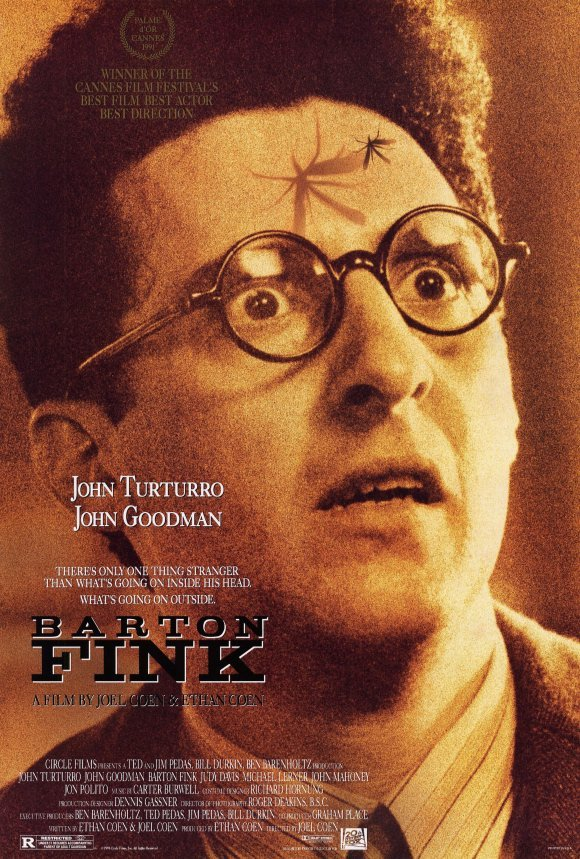

By 1991, Joel and Ethan Coen had done three very different pictures, but they all shared some connection to crime fiction, not to mention a fondness for labyrinthic plotting. With their next project, though, the Coen brothers truly defied everybody’s expectations…

Barton Fink is a period piece, set in 1941, about a leftist New York playwright who goes to Hollywood to work on a wrestling picture and ends up going insane (depending on how literally you read the film). The titular lead, so keen to speak for the people yet so blind to the rise of fascism and to the march to war, is masterfully played by John Turturro, who manages to combine innocence with arrogance, idealism with self-absorption. The other powerhouse performance is by John Goodman, who takes over the screen as Fink’s ‘average working man’ next-door neighbor in the hotel where much of the action takes place (one of the most haunting settings I can recall, from the peeling wallpaper to the sounds travelling through the pipes…). This duo helps ground the human drama among the increasingly intense, doom-laden atmosphere adorned with fanciful symbolism, whether religious (everything about the hotel is hellish), political (the situation in Europe is amusingly personified by a couple of LA cops), or psychological (constant references to missing heads and to the ’life of the mind’). Between the horrific hotel and the theme of writer’s block, there are evident parallels to The Shinning, especially in the surreal climax. Yet the Coens’ weirdest masterpiece – written when they were dealing with their own creative block, during Miller’s Crossing – carves out a very distinct mix of psychological horror and existentialist allegory about alienated artists, injecting it with a full-blown parody of the film industry.

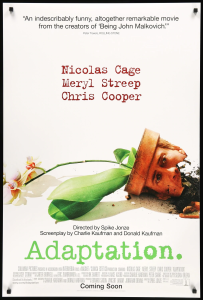

Written by Charlie Kaufman and directed by Spike Jonze, 2002’s Adaptation shares more than a few features with Barton Fink. For one thing, this too was an out-of-the-left-field follow-up to the creators’ previous collaboration, Being John Malkovich. As Kaufmann fictionalizes his own struggle to adapt a non-fictional book about flowers, we get yet another disjointed tale, unabashedly satirical and metafictional (including a couple of neat post-credits jokes), about a narcissistic screenwriter with an identity crisis who gets constantly interrupted by someone with whom he has an awkward relationship (in this case, both characters are played with impressive nuance by Nicholas Cage). The two films are pretty masturbatory, figuratively speaking, even if Adaptation is much more concerned with actual masturbation… The main similarity, however, is how original and ultimately unclassifiable each one is, breaking rules left and right and making one surprising choice after another, leaving it up to the viewers to decide what is real, what is not, and whether or not they should care.

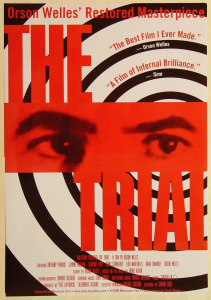

As far as recommendations go, the other obvious route would be to look back in time, rather than forwards, and point fans to the preceding lineage of brilliant self-reflexive comedies in which filmmakers dramatized their doubts about their work (Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels, Federico Fellini’s 8 ½, Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories). However, I’d rather highlight a movie that, while less thematically linked, is tonally much more similar to Barton Fink. Orson Welles’ The Trial adapts Franz Kafka’s classic novel about a bureaucrat who is told he’s under arrest and desperately tries to prove his innocence without even knowing what he’s being charged with. Nightmarish and absurdist, the film is pitched at the level of all those sequences in which Barton Fink appears lost in a world beyond his grasp – and not only does Anthony Perkin’s performance match Turturro’s hysteria, but most characters speak in the same kind of quick-paced, non-sequitur-heavy dialogue as the Coens’ various Hollywood types (the encounters with the cops, in particular, are remarkably close). Add to this The Trial’s pyrotechnic cinematography, extravagant set design, and the mood of encroaching totalitarianism and you can see why these two would make one hell of a double-feature!

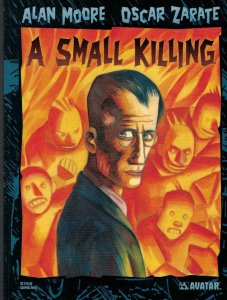

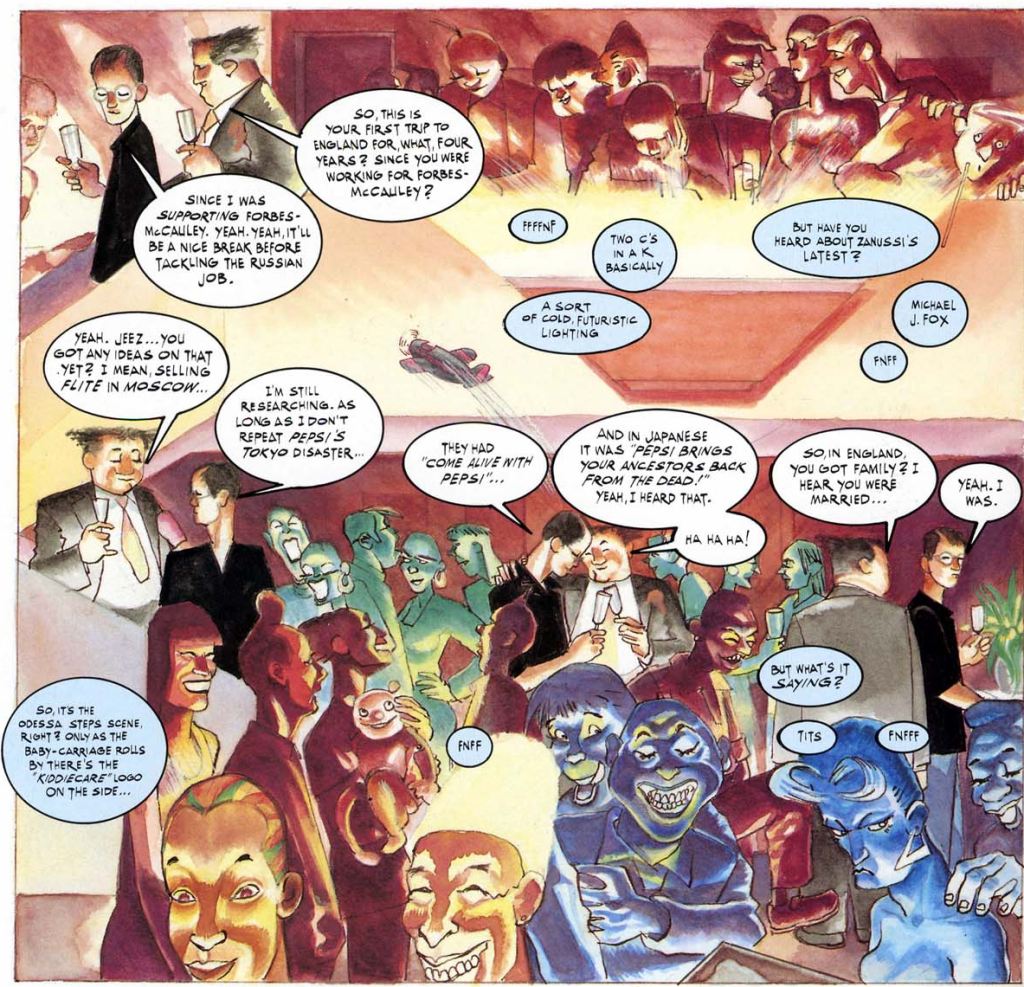

In comics, the closest equivalent I can think of is the 1991 graphic novel A Small Killing, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Oscar Zárate – who also did the idiosyncratic colors – about a British ad executive tasked with creating, not a wrestling picture, but a campaign for an American drink in a Russia increasingly open to western capitalism (in the twilight of the USSR).

A Small Killing

A Small Killing

As the protagonist, Timothy Hole, travels back to the country where he grew up, we follow his memories of past relationships and fading leftist idealism. Possibly my favorite Alan Moore comic – which I reread at least once every five years or so – this is an introspective character piece about growing old, but one intricately woven into larger politics, as Timothy embodies the yuppie culture of Thatcher’s Britain and, ultimately, the triumph of western imperialism in the Cold War… whose arrogance has gained a whole new light from today’s vantage point. (For the creators’ revealing take on the book’s underlying themes and background, I recommend reading the afterword ‘Anatomy of a Killing’ first published in Avatar’s 2003 edition.)

Technically, A Small Killing is as ingeniously formalist as any of Moore’s other masterworks from the late 1980s, with a tight structure (the chapters and flashbacks are organized through a specific progression, framed by the speed of different means of transportation) and plenty of symbolism, especially of compromised innocence/childhood (broken eggs, abortions, Lolita, etc). Yet the writing is witty enough to bury the techniques beneath the surface and Oscar Zárate’s art style is much looser than, say, that of Dave Gibbons or Brian Bolland, so the result feels more intimate, oneiric, and organic than Watchmen or The Killing Joke.

Besides the content, I’d argue the very significance of A Small Killing in the world of comics is comparable to Barton Fink. The book marks a moment in which several creators who had revolutionized genre narratives temporarily ventured – much like the Coens at the time – into a set of experimental, existentialist masterpieces about creativity and identity crisis, such as Neil Gaiman’s and Dave McKean’s Signal to Noise, Kyle Baker’s Why I Hate Saturn, or, a bit later, Grant Morrison’s and Jon J. Muth’s The Mystery Play, not to mention Peter Milligan’s and Duncan Fegredo’s Girl.