It’s been a while since I’ve done one of these!

After the critically acclaimed maturity and sensitivity of Fargo, Joel and Ethan Coen pulled yet another switch by delivering a stoner crime comedy packed with profanity (it was as if Tarantino had followed Jackie Brown with Pulp Fiction, rather than the other way around). Set in Los Angeles, against the backdrop of the 1991 Gulf War, The Big Lebowski (1998) revolves around a middle-aged hippie who calls himself The Dude and who just wants to drink, get high, and bowl with his buddies… but inadvertently finds himself wandering through a Chandleresque detective story. A suitably meandering – and seemingly random – opening narration identifies this slacker protagonist as ‘a man for his time and place,’ which is droll both because he seems so far from the typical American gung-ho entrepreneur hero of the yuppie age and because almost everyone in the movie has their head in some other era (most notably the Dude’s closest friend, a loose-cannon vet who just won’t shut up about Vietnam). It’s perhaps a pointless – and probably endless – task to try to explain everything that makes The Big Lebowski so laugh-out-loud funny, but I’ll highlight the fact that it pushes one of my favorite Coen devices to hilarious extremes: in the Coens’ scripts, characters always have very personal speech patterns, but they also tend to pick up lines and expressions from each other, like in real life, which leads to many multilayered exchanges, including a priceless bit here where the pacifist Dude actually repurposes the words of George H.W. Bush!

With its perfect casting, bouncy direction, and eminently quotable screenplay, this has been my favorite Coen picture ever since I first saw it, at the time. Despite having read a couple of lukewarm reviews, I remember going into the theater with high expectations because I was such a fan of the Coen brothers and yet still being blown away by a movie where every single scene seemed pitched at my personal tastes and sense of humor. And I know I’m not alone: The Big Lebowski has become a veritable cult phenomenon and left more of a lasting, widespread mark on popular culture than any of the brothers’ remaining output (one of the weirdest manifestations of this was an amusing episode of the children’s superhero cartoon show Powerpuff Girls built almost entirely out of references to The Big Lebowski).

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice feels like an unofficial prequel to The Big Lebowski… Joaquin Phoenix plays a counter-culture detective in 1970 who could easily be a younger Dude. We also get another off-kilter narrator to go with the stoner protagonist wandering through an intricate California-based mystery. Both pictures are moody, semi-surreal comedies that get their humor less from clear punchlines than from amusing turns of phrase, quirky characterization, and creative cinematography. That said, Anderson has different ambitions. His script adapts a satirical novel by Thomas Pynchon, who crammed in every single conspiracy theory from the early seventies, thus capturing that era’s sense of paranoia and of crumbling dreams from the previous decade. Since Magnolia, Anderson has carved out a reputation as the auteur of heady, occasionally perplexing dramas (Punch-Drunk Love, There Will Be Blood, The Master, The Phantom Thread) – and you’d be forgiven for suspecting Inherent Vice fits the bill, given that many critics painted it as an impenetrable mess. However, while the super-complicated plot is indeed hard to follow in every detail, the story does make sense diegetically if you’re willing to put in the effort to figure it out (the clues are there, although the solutions to the various mysteries aren’t always explicit). In any case, even if you lose the thread of the narrative, you can still enjoy Inherent Vice as a trippy exercise in style, since each scene is peppered with delightful eccentricities and atmosphere. (In that sense, the film anticipates the carefree vibe of Licorice Pizza.)

The Big Lebowski and Inherent Vice would form a perfect triple-bill with Shane Black’s The Nice Guys, another hilarious dark comedy about a messed up LA detective, set in the late seventies. This one is much more frantic, though, with Ryan Goslin giving a particularly over-the-top performance as a horny private eye with loose ethics and a drinking problem. He is joined by Russel Crowe as a hired enforcer who seems to have it more together (scarily so, at times) and Angourie Rice as his plucky teenage daughter who steals every scene she’s in. Once again, the mystery plot is mostly a vehicle for having the protagonists bump into all sorts of oddball characters – from porn-producing activists to the fiercest contract killer to grace the screen in recent memory – although, like P.T. Anderson, Black also includes quite a few nods to the era’s political conspiracy thrillers, culminating in a cynical jab at the car industry.

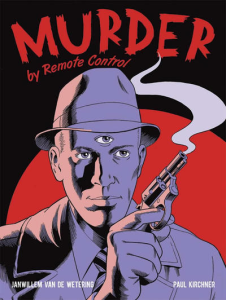

There are plenty of funny, labyrinthic crime comics laden with sex and drugs (for instance, in previous posts I recommended Stray Bullets and The Fix), but the magic of The Big Lebowski isn’t just about the story, the characters, and the jokes, but also, as mentioned, about the way the framework of an investigation organizes a series of bizarre encounters – and, yes, a couple of memorable full-on dream sequences. With that in mind, my final recommendation is the psychedelic graphic novel Murder by Remote Control:

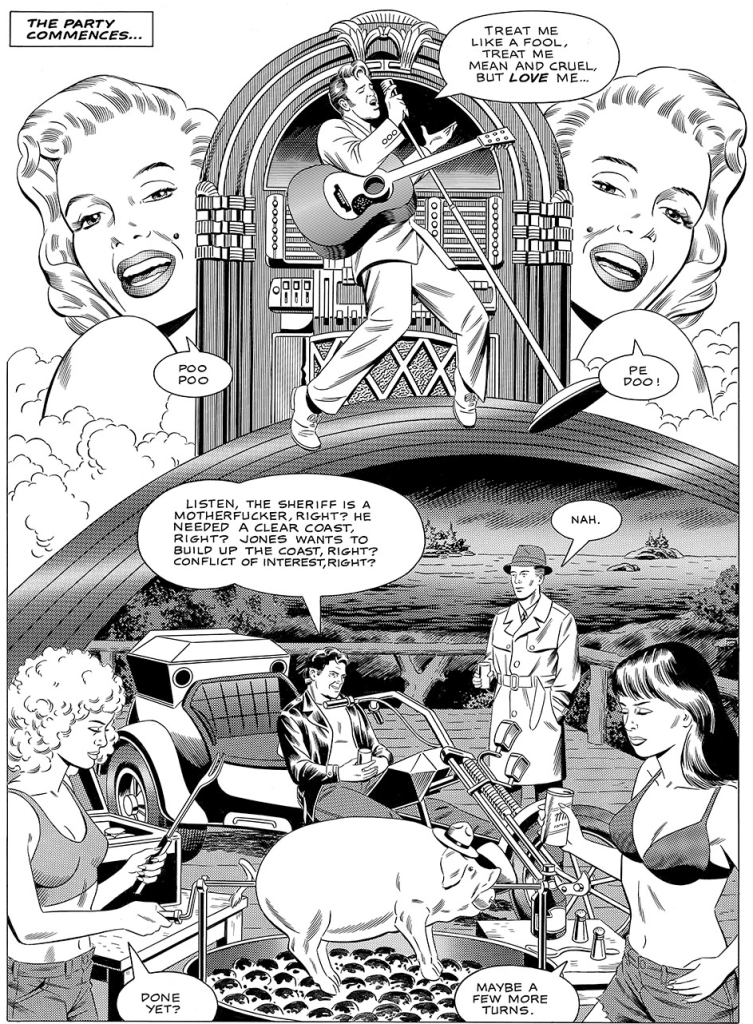

Originally published in the Netherlands in 1984 (and, in the US, in 1986), Murder by Remote Control is itself a cult object. With lavish artwork by Heavy Metal veteran Paul Kirchner and a baffling script by Dutch mystery writer Janwillem van de Wetering, this is a whodunit set in Maine, where Zen detective Jim Brady investigates the death of an oil tycoon killed by a toy plane – a premise that serves as the pretext for dreamy interrogation scenes with a row of idiosyncratic suspects.

Like many comics by European creators, Murder by Remote Control is a book about what the United States symbolizes, both explicitly (‘Let’s see what might happen if two of America’s great forces, the quest for productive success and the desire to enjoy the unspoiled environment, lock in mortal combat.’) and in the way the victim and each suspect embody cultural icons, from the motorcycle-riding rebel Joe McLoon to the retired Hollywood star Steve Goodrich (who, with his caretaker Erik van Heineken, seems straight out of Sunset Boulevard, even though he looks like Gary Cooper). Like in The Big Lebowski, we are treated to a tour of caricatural American archetypes, including yet another despicable chief of police. These figures aren’t necessarily complex, but they do paint a rich tapestry of associations linking disparate elements of US mythology.

The twist is that Jim Brady isn’t the Dude, but rather a tidy, focused investigator – or, as Joe McCulloch put it, the apparatus of investigation itself – who seems able to gaze into hidden depths of the suspects’ minds (I wonder if this inspired Fred Van Lente’s and Guiu Vilanova’s nifty Lovecraftian comedy Weird Detective). As a result, most pages feature surrealistic compositions, albeit rendered in an oddly naturalistic style that presents Brady’s visions as a linear prolongation of ‘reality.’ Kirchner’s hypnotic illustrations thus forge a peculiar path between a mystical and a parodic look.

(I strongly recommend Dover’s 2016 edition, which – unlike the previous version – not only reprints the work in its original size, but it also contains an introduction by Paul Kirchner looking back at the project’s origins and a great afterword by Stephen Bissette.)