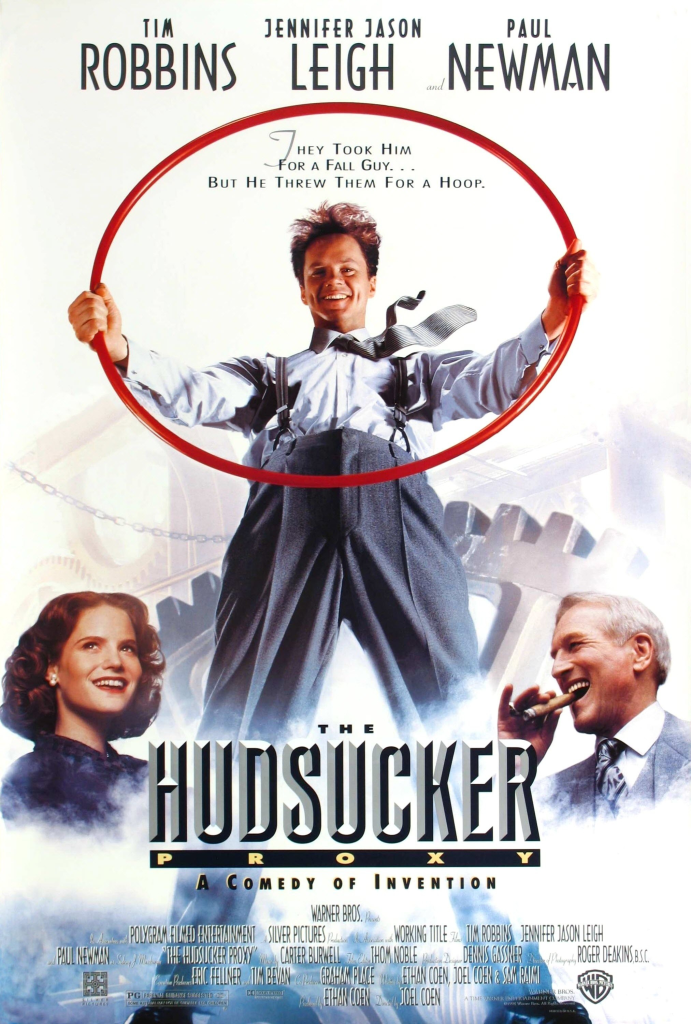

For their fifth film, Joel and Ethan Coen went back to the slapstick tone and rhythm of Raising Arizona, once again channeling the Looney Tunes, only this time around blended with the flavor of old Hollywood screwball comedies about big business and world-weary, wisecracking reporters, complete with a romantic subplot. Set in an overblown version of 1958 New York City, the uproarious The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) sees clumsy mailroom clerk Norville Barnes (a wide-eyed Tim Robbins) suddenly get promoted to president of a large corporation as part of the board’s ploy to manipulate their stock price. You can perhaps imagine where the farce goes from there (although I doubt you’ll anticipate the climactic fistfight!), but the movie’s joy lies, above all, in the surrealist way the Coens depict capitalism at work, from the Modern Times-like frenzied masses of the mailroom at the – literal and symbolic – bottom of Hudsucker Industries to the grotesque executives chomping fat cigars at the top (led by a gleefully machiavellian Paul Newman) and all the departments in-between, connected by pneumatic tubes and a crowded lift. None of this is subtle and it’s not meant to be: the Coen brothers (co-writing with Sam Raimi, who lent them some of his manic energy) have basically given life to an outrageous editorial cartoon… although, to be fair, it looks less exaggerated every day.

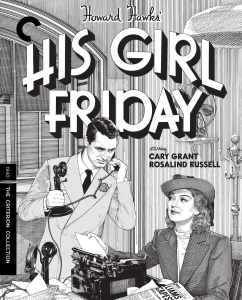

Given that you could accurately begin to describe The Hudsucker Proxy as Executive Suite meets Christmas in July and One, Two, Three (with a dash of The Producers), there are plenty of links to explore when searching for related films, especially once you factor in the aesthetic influence of Metropolis and Brazil. If I was to recommend just one of the Coen brothers’ sources of inspiration, however, my vote would go for 1940’s His Girl Friday, whose chain-smoking, fast-talking atmosphere blatantly informed the newsroom scenes and whose protagonist Hildy Johnson was lifted for THP’s most charismatic character, workaholic newspaperwoman Amy Archer (Jennifer Jason Leigh nails the same mix of intelligence and confidence, with a touch of sentimental confusion). When he was not directing dramas about male comradery, Howard Hawks usually made comedies about the battle of the sexes, so here he took a witty play about the ludicrous, heartless extent the press was willing to go for a sensationalist story and added an extra layer: Johnson’s former editor is also her former husband, who tries to manipulate her into both getting back to journalism and getting back to their marriage. Inevitably, there are curious choices that come with a production made so long ago (the news story being investigated involves a white man sentenced to death for shooting a black cop), but the overall cynicism about media, politics, and gender expectations remains shockingly recognizable – and damn funny! Hawks’ direction is less exhibitionist than the Coens’, but the pace is just as relentless, with the leading ex-couple – enthusiastically played by Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant – spouting quippy dialogue at a speed that is bound to make you dizzy.

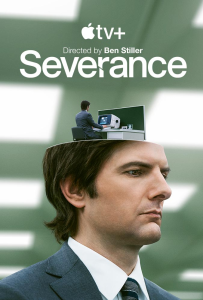

In terms of more recent works that seem to follow in The Hudsucker Proxy’s footsteps, there are also several strong candidates, from the labor-rights satire Sorry to Bother You to the absurdist BoJack Horseman (whose final seasons also feature a hilarious version of Hildy Johnson). Yet, like last time, I’d rather highlight a less obvious relative… It’s not BoJack, but it’s a TV series as well (the creativity and production values on the small screen have come to match those of cinema, so it doesn’t feel like a cheat). Although not as wacky as the Coen brothers’ film, Severance, created by Dan Erickson, also involves a surreal, retro-looking company and plenty of morbid humor, not to mention an ultra-stylish direction (courtesy of Ben Stiller and Aoife McArdle). The show’s premise concerns a procedure that allows workers to radically split their consciousness between their office and non-office existence, effectively creating a double personality, which you could take as either an allegory about alienation or as an alternative to a world in which the division between private and professional life seems increasingly blurry. Apart from the social resonance of the fantasy of separating – or conciliating – these two sides of life, the concept serves as a springboard for thoughtful science fiction, exploring the psychologies and imagining the logistics and ramifications that would surround such a technology. While melancholic rather than frantic – and certainly more emotionally invested in its characters – Severance thus offers its own bizarre, visually daring, over-the-top take on the ruthless power dynamics of the corporate model. (Plus, it co-stars Coen regular John Turturro.)

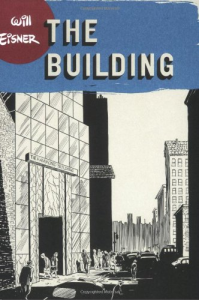

In turn, the graphic novel I chose this time is not a comedy, but it is pitched at a Coen-esque level of expressionism…

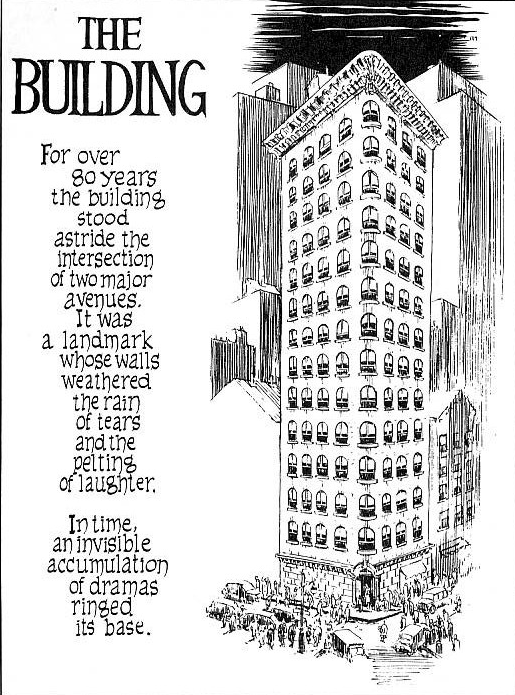

One of The Hudsucker Proxy’s most memorable features is its lavish set design, with most of the film built – narratively, thematically, and visually – within and around a huge skyscraper that shapes the characters’ lives as they move through the various floors and offices (and frequently jump or fall out of windows). Taking as a starting point the notion that such edifices, ‘barnacled with laughter and stained by tears,’ cannot help but ‘somehow absorb the radiation from human interaction,’ The Building sets out to capture some of the ‘invisible accumulation of dramas’ ringed at the base of another NYC skyscraper. Written, drawn, and lettered in Will Eisner’s signature melodramatic style, the book reflects the veteran creator’s later-life concern with chronicling the personal sagas of the ‘invisible people’ that made up the crowds of New York throughout the 20th century. In turns bittersweet, nasty, and uncompromisingly devastating, The Building at first appears to be an anthology of four powerful tales, but they’re all brought together at the end through a venture into magic realism that wouldn’t feel out of place in the Coens’ movie.

(Originally published as a single piece in 1987, The Building has also been collected along with other great comics in the hardback Will Eisner’s New York: Life in the Big City.)