After a whole month looking at spy fiction, it’s only fair I give you my take on the latest summer blockbuster, the spy thriller Mission: Impossible – Fallout. I’ll do that in the next post, though. First, some words about the television show that inspired this movie franchise, which first aired on CBS all the way back in 1966…

It’s no secret that the ‘60s produced some of the coolest spy shows in TV history. Me, I have quite the soft spot for the noirish Hong Kong, but my favorite has got to be Mission: Impossible, the Bruce Geller-created series about an undercover organization pulling off risky, ultra-complicated assignments for the US government. They’re called the Impossible Missions Force, aka IMF, but unlike the other IMF (International Monetary Fund) they actually know what they are doing!

I see what may put some people off: the labyrinthine plots occasionally stretch viewers’ suspension of disbelief (at least if you think about them too hard) and the ironclad formula can get tiresome… With a few exceptions, each episode focuses on a different, autonomous mission, starting with a debriefing scene and ending with the successful completion of the assignment, so you can argue that there is never any real suspense about the outcome. Plus, since the agents’ personalities are kept to a minimum, the emotional stakes aren’t too high either. That said, there are still many layers of enjoyment to get from this show…

First of all, despite being firmly set in the world of espionage, the series essentially revolved around heists and cons. More than any other of the early episodes, ‘Operation Rogosh’ set the tone and firmly established M:I’s main appeal: to watch a group of grifters pull off imaginative, ambitious scams on foreign operatives and domestic criminals. The ruses often involved surreptitious break-ins (in ‘The Traitor,’ the IMF even recruited a contortionist, played by future Catwoman Eartha Kitt), stealing McGuffins, and all sorts of switcheroos. In other words, the stories were all capers at heart, even if sometimes spliced with other genres’ DNA (‘Trek’ has a spaghetti western vibe, ‘Zubrovnik’s Ghost’ is shot like classic horror, the two-parter ‘The Council’ at times feels like a gritty crime flick).

It’s a show about tradecraft. The point is not whether or not the IMF team will succeed, but how. Basically, you spend half the time trying to figure out their plan as it unfolds and then, when it hits a snag, you see them improvise a way to get things back on track. The big payoff usually comes in the form of ‘oh shit’ moments as the villains/marks realize they’ve been played – that there was no earthquake (‘The Survivors’) or they were not underwater (‘Submarine’) or in 1937 (‘Encore’) after all.

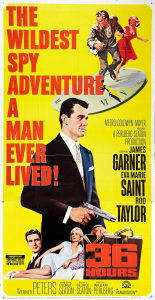

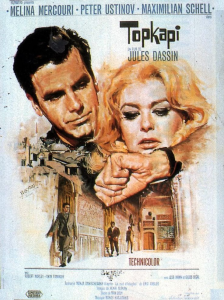

36 Hours, The Ipcress File, Topkapi, Alfred Hitchcock’s spy thrillers… the series’ influences shine through not just in terms of the type of left turns and cliffhangers it deploys, but in terms of style. Mission: Impossible (particularly the episodes directed by Leonard J. Horn) gets a lot of mileage out of offbeat camera angles, tense close-ups, and rhythmic jump cuts, not to mention Lalo Schifrin’s unforgettable soundtrack. In turn, the show probably inspired later films such as George Roy Hill’s The Sting, Spike Lee’s Inside Man, and Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s trilogy.

Speaking of films, although M:I can be seen as part of the tsunami of audiovisual spy fiction that followed the success of the first James Bond pictures, the show is definitely doing its own thing. It’s interested in straight-faced, cool-headed team work, not in a promiscuous, trigger-happy lone hero with licence to kill, a twinkle in his eye, and a quip for every occasion. Sci-fi gadgets, explosions, honey traps – those sometimes show up, but they’re hardly the norm. The biggest thrills take the form of carefully executed sleights of hand rather than wild action set pieces.

So yes, the whole thing is plot-driven and a bit cerebral. We know so little about the heroes that we are forced to focus on the missions themselves. The best writers (William Read Woodfields and Allan Balter) knew this, making sure that there was always at least one inventive concept to make each episode stand out, even when adhering to the policy of minimalist characterization. Every once in a while, you do get a small tweak to the pattern – by having one of the stars taken prisoner (including in the awesome ‘The Town’) or fall in love and jeopardize the mission (my favorite of this subgenre is ‘The Short Tail Spy’) – but those are minor exceptions. As a rule, then, why should we care about the characters?

One reason is how engaging the main cast can be as they smoothly shift from one fake identity to the next and then back to the concentrated expression of a specialist at work. While the IMF agents are ultimately interchangeable, it’s hard to deny the show hit a sweet spot in seasons 2 and 3, when Jim Phelps (Peter Graves) had already replaced the uncharismatic Dan Briggs (Steven Hill) as team leader yet the power trio of makeup artist/illusionist Rollin Hand (Martin Landau), versatile actress Cinnamon Carter (Barbara Bain), and tech wizard Barney Collier (Greg Morris) were all still around. By contrast, the last couple of seasons – 6 and 7 – were certainly the weakest in terms of acting (as well as in terms of scripts).

The other reason is the team’s adversaries. Sure, most villains weren’t too complex, either – they were given only enough psychological depth to enable them to go through the IMF’s sadistic traps and mind games (with the odd episode investing them with more nuanced motivations, like in ‘The Photographer’). However, they all had an arc and, for every guest actor who chewed the scenery, you had someone bringing in their A-game. Plus, they tended to be not only vain (the reason for their fall), but also quite cunning (making them a threat to the team’s plan), which was a joy to watch.

Again, this isn’t Bond’s fantasy world: rather than over-the-top rogues with goofy henchmen, we are mostly treated to petty, embittered bureaucrats and autocrats who’ll settle for much less than world domination. That said, some of the strongest episodes feature outstanding opponents who really push the IMF, like the brilliant investigator in ‘The Mind of Stefan Miklos’ (who seems like the other side’s equivalent of Jim Phelps) and the unpredictable hitman in ‘The Killer’ (who has no MO, choosing his methods at random and at the last minute, making his moves impossible to anticipate). Then again, ‘The Amateur’ entertainingly goes in the opposite direction, with a villain who is actually a nobody that just happens to cross paths with the IMF by accident (one of a handful of sleazy roles played by Anthony Zerbe).

‘Trek’ and ‘The Exchange’ (stills taken from Christopher East’s M:I episode ranking)

Another thing that captivates me is the series’ approach to the Cold War. In Mission: Impossible, most countries were either fictitious or unidentified, the USSR was referenced trough euphemisms (the opposition, the enemy), and during assignments abroad the actors feigned a loose foreign accent, so you didn’t really know which language they were supposed to be speaking. There were all these fuzzy locations beyond the ‘iron curtain’ with gibberish street signs and characters with generic, Eastern European-sounding names who called each other ‘comrade,’ but communism itself was rarely more than hinted at (as opposed to fascism, which was discussed quite explicitly in the excellent ‘The Legend’). At the end of the day, IMF missions were just about moving geopolitical chess pieces in order to secure US interests. What you were left with was the Cold War at its most abstract, as pure game theory removed from ideology and contextual specificities…

(In ‘Invasion,’ we do get a bleak glimpse at the annexation of the US by the European People’s Republic, but the focus is exclusively on a military tribunal, telling us nothing about the rest of society. In any case, it’s all an IMF simulation in order to trick a double agent, so, while the ensuing dystopia can be taken as a reflection of how the team envisioned their worst nightmare, it can just as easily be seen as a strategic distortion in order to get their way.)

Ironically, by privileging Hitchcockian suspense over world affairs, I’d say the show managed to both be more exciting and make a bolder statement than Hitchcock’s later forays into this territory (Torn Curtain and Topaz). In IMF’s paranoid reality, everything was smoke and mirrors – on the one hand, you had all these masters of disguise staging events to expose the pretenders in power; on the other hand, M:I normalized the idea that there was order underneath the chaos, that there was always someone behind the wall, or under a latex mask, pulling the strings… (Even today, if you check out the newspaper right after watching an episode, you’re bound to feel suspicious as you read about the latest scandals and diplomatic turnarounds.)

That’s why it’s so neat when the show sort of goes meta and has the IMF subvert the opposition’s own attempts at deception. In ‘The Carriers,’ the team (plus George Takei) pose as enemy agents while infiltrating a training camp for foreign spies in the form of a recreation of an all-American town… So on one level you get to see how the show’s writers imagined the communists imagined them. And on another level – within the story – you get to watch a bunch of US agents pretending to be Soviet agents who are pretending to be US agents (presumably, the IMF agents themselves previously went through a parallel sort of training, since they’re so good at passing off as commies). It’s all a bit mindboggling and a lot of fun, especially the scene where Rollin Hand is taught the American way to buy hotdogs!

There are a few more of those. ‘The Play,’ in which Cinnamon stages an anti-American theater production in a socialist country, is genuinely perverse, as the IMF’s plan consists of encouraging the premier’s propensity for censorship in order to get rid of an eager minister of culture. It’s an unusually funny entry, too, which both satirizes propaganda and works as a slick propaganda piece itself. Moreover, in ‘Action!,’ the team films an enemy director filming fake footage of US war crimes (presumably in Vietnam). Thus, exactly one year before the My Lai massacre, this fascinating episode suggested that anti-war documentaries could not be trusted and US covert operations, if anything, were bringing the truth to light!

‘Hunted’ and ‘The Reluctant Dragon’

All this brings me to the point that you can just as easily see the IMF as the bad guys. After all, they are a secret organization who regularly disrupts other countries’ regimes and, even if not pulling the trigger directly, often sets up assassinations. M:I has us rooting for them by giving them sympathetic assignments: they sometimes prevent terrorist attacks or go after Nazis, mobsters, and heroin dealers. Season 5 even features a couple of memorable episodes with missions against apartheid (‘Hunted’ and ‘Kitara’). However, anyone familiar with the history of American black ops cannot help but feel suspicious.

Not that the show stayed completely away from ambiguity. Curiously, one of the most openly political episodes, ‘The Reluctant Dragon,’ went out of its way to complexify the feelings of people in the Eastern Bloc (it also featured a rather callous scheme by Rollin). In 1970, when countercultural backlash had become inescapable, ‘The Martyr’ twisted things around by having the IMF incite a student revolution abroad (one of the agents even gave a full rendition of Bob Dylan’s The Times They Are a-Changin’). This nifty episode provocatively blurred the lines not just between American hippies and foreign communists, but also between the iconography of leftist rebellion and the tools of US imperialism (Barney used a funky medallion and a Marxist treaty on agrarian reform to counteract a truth-serum-based interrogation). More clumsily, ‘The Innocent’ tried a different response by having the team recruit a young conscientious objector.

Regardless, I’d argue the issue is more structural. Since only the IMF’s foes get character development, it’s hard to avoid at least a bit of empathy with them as we see them being methodically manipulated towards their downfall. For example, even though ‘Phantoms’ pulls off one of the show’s most effective depictions of a socialist authoritarian system, Luther Adler’s performance imbues his ageing dictator with such an engrossing mix of ruthlessness and vulnerability that his final humiliation comes across as somewhat touching and tragic.

Rather than undermine the premise, these are the sort of contradictory readings and emotions that make Mission: Impossible such a stimulating treat.