Given how bombastic and out-of-control the Batman series has become of late, I figure the time is right to revisit the concept of comics as manic, trippy escapades. When I suggested a bunch of Non-Batman balls-to-the-wall adventure comics earlier this year, I focused on recent books, but of course there is a long tradition of ambitious and exciting stories that mix wild action with genuinely mind-blowing ideas!

Here are some of the most over-the-top classics:

ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN

To sum up the plot of 1986’s Elektra: Assassin would be to do it a disservice. Surprising as it may seem, it’s not really the orgiastic combination of ninjas, spies, demons, cyborgs, mind control, ultra-violence, and Cold War politics that makes this comic such an incredible ride. It’s mostly the way the story is told, with overlapping stream-of-consciousness narration and flashbacks frantically discharged onto the page by Bill Sienkiewicz’s unmistakable, impressionistic watercolors. If Frank Miller’s aggressive writing style has always bordered on parody, Sienkiewicz’ caricatural art nails the series’ extravagant satire while making every page a delight to look at.

In a way, Elektra: Assassin is the high point of the explosion of creativity its authors underwent in the ‘80s – there are traces of Miller’s Ronin and hints of Sienkiewicz’s Stray Toasters, but it outmatches any of those works in terms of freewheeling experimentation. Hell, as far as sheer exuberance goes, this book makes Frank Miller’s Batman comics from that era appear tame and uninspired in comparison!

Elektra: Assassin

Elektra: Assassin

Sadly, the adventures of Elektra Natchios never reached the same heights again. Frank Miller returned, with his own impressive pencils, in Elektra Lives Again. Chuck Austen, Scott Morse, and more recently Mike Del Mundo have all approached the character with relatively unconventional art. In the early 2000s, Greg Rucka wrote his signature hardass-broken-woman type of yarn. Robert Rodi and Sean Chen did a fun run after that. Yet no one has been able to beat Assassin’s awesome closing punchline.

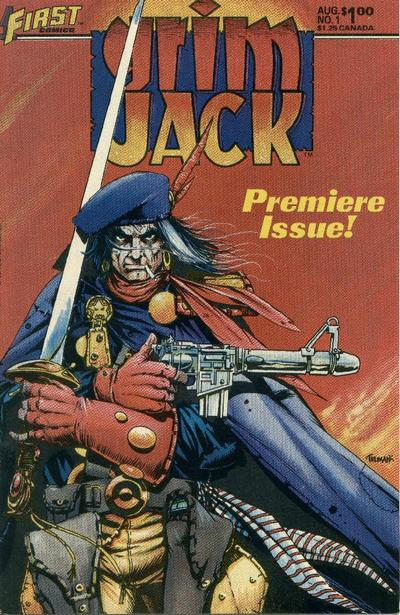

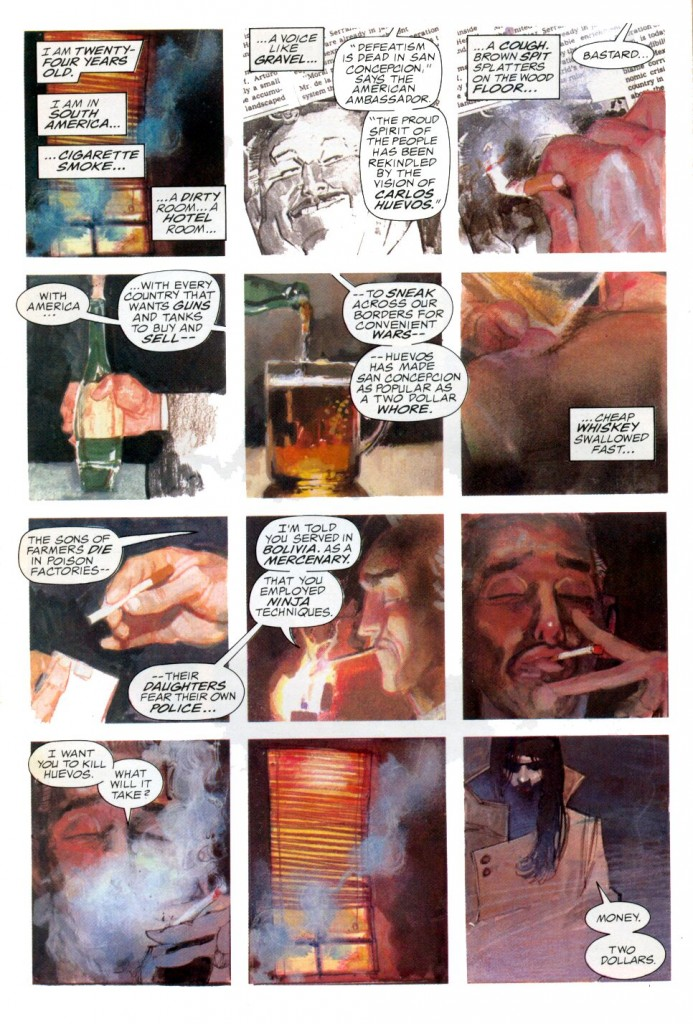

GRIMJACK

Name your favorite pulp genre and you’re likely to find it somewhere on the pages of this comic. Not only is John Gaunt, aka Grimjack, a mercenary/hardboiled detective/war veteran/ex-cop/ex-gladiator, he operates out of the pan-dimensional city of Cynosure, an intersection between all dimensions where each block has a distinct atmosphere (complete with its own physical laws). This formula allows the series to freely combine all sorts of tropes and aesthetics, from cyberpunk to western to sword-and-sorcery mayhem. There is even some subversive comedy around Cynosure’s ultra-capitalist system in which, at one point, the only ones with legal rights are corporations! (‘An individual had rights if the family could afford to incorporate – the parents were CEO and Chairperson and the children were considered assets. Marriages were as much mergers as anything else.’)

Created by John Ostrander and magnificently brought to life by Tim Truman’s stark designs, it’s hard to believe GrimJack was one of their first professional comic works. Ostrander and Truman hit the ground running, already displaying the bravado that would make them the masters of smart action stories, thanks no doubt to editor Mike Gold, the man behind some of the eighties’ most badass runs, including Grell’s Green Arrow, O’Neil’s The Question, and Kupperberg’s Vigilante (not to mention indie classics like Jon Sable Freelance, Badger, and American Flagg!). Indeed, I wonder why this series isn’t as widely remembered as some of those…

In particular, fans of Ostrander’s tough-as-nails dialogue will have a field day:

Grimjack #7

Grimjack #7

As usual with John Ostrander, he was not afraid to drastically shake up the status quo every once in a while, including radical changes to the protagonist and his city. The changes were mirrored by visual shifts – starting in issue #31, art duties were taken over by Tom Mandrake (who would go on to illustrate many other great series written by Ostrander) and then in #55 by Flint Henry, whose wonderfully detailed draftsmanship was quite a contrast to Mandrake’s sketchy artwork.

To top it all off, Grimjack owned Munden’s Bar, a surreal joint for lowlifes of all species (think Mos Eisley cantina), and hung there between missions. This bar got its own quirky, long-running backup feature, mostly co-written by Ostrander and Del Close, with art by a veritable who’s who of cartoonist geniuses (plus a barrage of background cameos and sight gags). In fact, looking at each issue’s credits section, it’s amazing how much first-rate talent was involved in this series across the board.

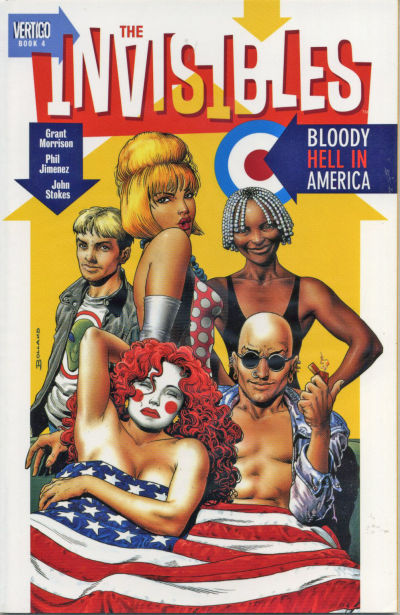

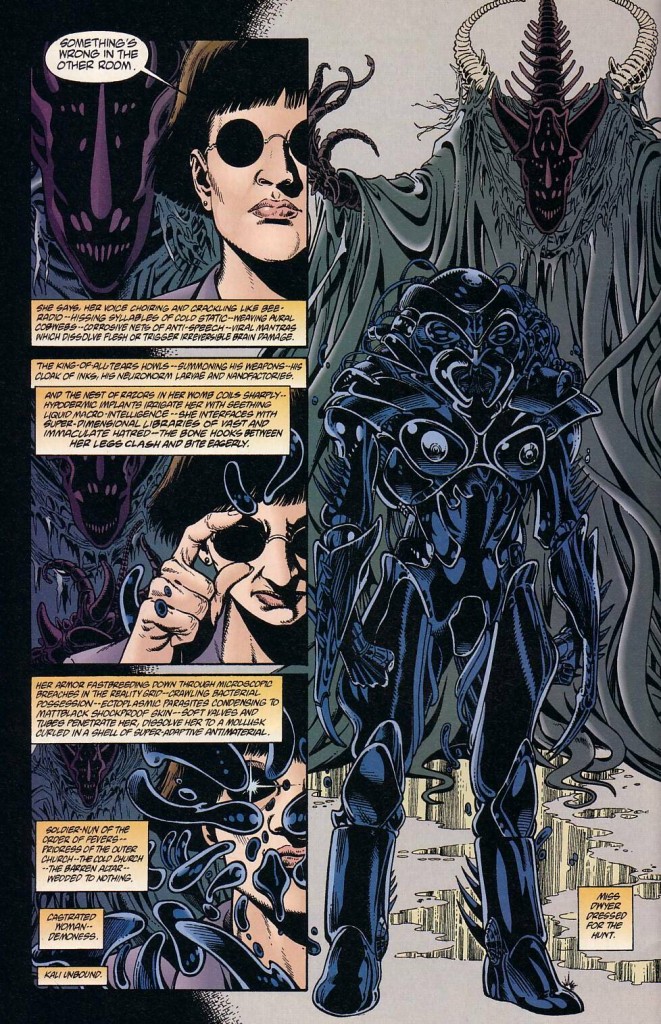

THE INVISIBLES

The Invisibles seems to have a mixed reputation as both one of the coolest comics ever and as a confusing, esoteric acid trip that’s largely impenetrable even by Grant Morrison’s standards. In fact, for all the crazy magic, sex, sci-fi, and metafiction, this can be seen as quite a straightforward series about a secret organization struggling against the forces of oppression. It’s just that the villains happen to be inter-dimensional alien gods who have enslaved humanity. And the heroes are a ragtag team made up of a teen vandal, a futuristic witch, a transgender Brazilian sorcerer, and a former policewoman called Boy, initially led by the charismatic super-assassin King Mob. Oh, and parts of the story hinge on time-travelling, the ghost of the Marquis de Sade, and the severed head of John the Baptist.

A cult comic if there ever was one, Morrison’s magnum opus is a fascinating modern fantasy saga full of poetic, existential musings. Early on, one character lays it out: ‘Your head’s like mine, like all our heads; big enough to contain every god and devil there ever was. Big enough to hold the weight of oceans and the turning stars. Whole universes fit in there! But what do we choose to keep in this miraculous cabinet? Little broken things, sad trinkets that we play with over and over.’

To be sure, The Invisibles is tonally all over the place, but the fact that it’s such a disjointed mess actually fits in with the series’ rebellious themes. The first book features a beautifully written conversation between Lord Byron and Mary Shelley that wouldn’t look out of place on the pages of The Sandman. The series then turns into a terrific horror title in line with the Vertigo house style of the time, before going full throttle into apocalyptic science fiction mode and culminating in a transcendental mindfuck. As if this wasn’t enough, the artists kept changing, each with a wholly distinct style, ranging from Jill Thompson’s elegant pencils to Philip Bond’s adorably blocky linework, with a huge chunk done in Phil Jimenez’ glossy hyper-realism.

The Invisibles #19

The Invisibles #19

With its in-your-face, anti-authority attitude and violence and energy and drugs, this is also one goddamn punk comic. Although spliced with New Age mystical mumbo-jumbo, The Invisibles’ anarchist spirit of conspiracy theories and counter-culture terrorism channels the Sex Pistol’s rage-against-whatever posturing and Banksy’s street art while anticipating Anonymous’ technoactivism. At the same time, the series still combines enough thought-provoking layers to encourage multiple readings and ambiguous interpretations, as Morrison sneaks in touching character moments and subplots – like in the brilliant issue ‘Best Man Fall,’ which zooms in on a henchman’s complex, multifaceted life before he’s killed by King Mob.

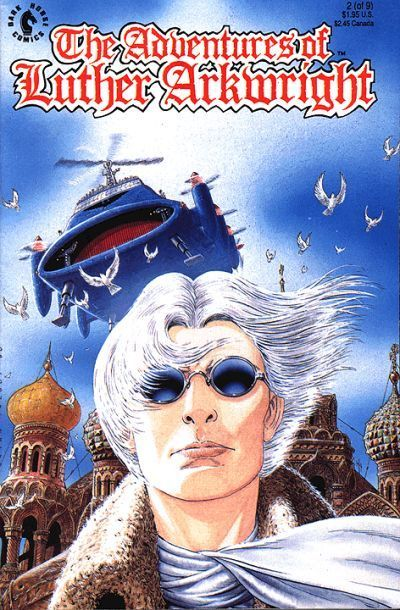

THE ADVENTURES OF LUTHER ARKWRIGHT

Only slightly less psychedelic and messed up than The Invisibles, Bryan Talbot’s The Adventures of Luther Arkwright follows a secret agent with psychic powers who fights the sinister Disruptors across parallel universes. It’s above all a work of gritty speculative fiction, as most of the action takes place in an alternate Earth where the monarchy lost the English Civil War, so Talbot designs a detailed dystopia ruled by Puritan dictatorship. The first chapters are a bit rough, with fragmented flashbacks and non-linear storytelling illustrated by experimental black & white artwork, but the narrative gradually becomes more focused towards the end (although not before a series of brain-melting splashes where the main character dies and apparently fucks all of creation before being resurrected, more powerful than ever).

As dense and challenging as The Adventures of Luther Arkwright can be, it’s also an absorbing read. During the climax, in Cromwellian London, Talbot throws everything at us, including a bloody revolution, a ticking time bomb, a childbirth, a military invasion by the Russians and the Prussians, a trans-dimensional invasion by the Disruptors, and an ancient cosmic doomsday device that threatens the entire multiverse.

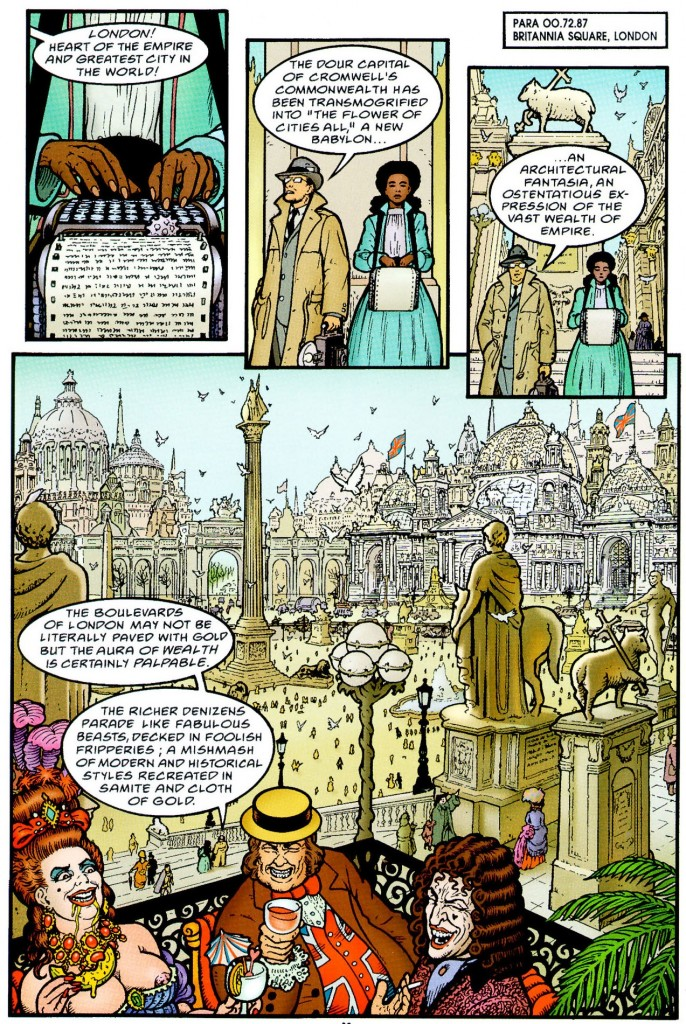

That said, I think I still prefer the sequel, Heart of Empire or The Legacy of Luther Arkwright, which is a deranged take on imperial epics like Quo Vadis and Star Wars:

Heart of Empire

Heart of Empire

Set two decades after the events of the original and focusing on the surviving cast, Heart of Empire paints a complex tapestry of political and telepathic intrigue over a luscious-looking proto-steampunk world ruled by debauched royalty. Bryan Talbot thus secures his place in the long line of sci-fi comics writers who have ingeniously reimagined British imperialism, such as Peter Milligan in Tribal Memories, Warren Ellis in Ministry of Space, and Ian Edginton in Scarlet Traces (a neat sequel to H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds).

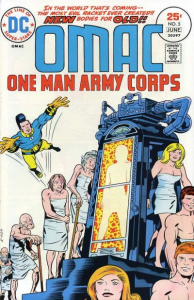

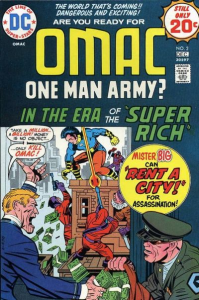

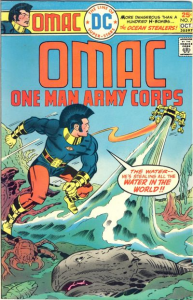

OMAC: ONE MAN ARMY CORPS

First published in 1974, the short-lived OMAC: One-Man Army Corps takes place in what the typically hyperbolic narration keeps calling ‘THE WORLD THAT’S COMING!’ On the one hand, these are nightmarish visions of the future by an artist engaging with issues like war, technology, alienation, and consumerism. On the other hand, that artist is Jack Kirby, so the result revolves around Buddy Blank, a harmless employee of Pseudo-People, Inc. who is transformed into a super-soldier with a blue mohawk via remote-controlled hormone surgery done by a sentient space satellite called Brother Eye. Also, at one point he fights with a monster that looks like a flying octopus on top of Mount Everest.

This series allegedly came about in order for Jack Kirby to fulfill his quota of 15 pages per week at DC. (Yes, 15 pages per week!) Kirby wrote, penciled, and edited the comic, which means it’s packed with bizarre visuals, awkward dialogue, and all sorts of throwaway ideas springing from his notoriously effervescent mind. In the first pages alone, we are introduced to the nameless officers of the Global Peace Agency, who conceal their faces with cosmetic spray so that they can represent any nation, and to the Psychology Section of Buddy’s company, where employees can take out their frustration by burning cars or kicking lifelike mannequins in the butt. And that’s all before our hero is assigned ‘test parents’ by the computer of the Social Engineering Division…

Make no mistake: reading OMAC is a far-out experience. Seriously, the only reason this isn’t the most insane futuristic comic ever is because at the same time Kirby was also working on the post-apocalyptic Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth, which is essentially a feverish version of Planet of the Apes!

OMAC’s initial run lasted for only 8 issues, but it was of course a matter of time before someone revisited Kirby’s baffling creation. In 1991, a prestige mini-series expanded Buddy Blank’s saga, further cranking up the science fiction by adding serpentine time-travel paradoxes. This project was handsomely written and illustrated by John Byrne, who approached it with straight-faced restraint and grit yet didn’t resist the chance of throwing the storyline into high gear by pitting OMAC against Adolf Hitler (because comics).

In 2011, Dan Didio and Keith Giffen fully rebooted OMAC and placed it in DC’s New 52 continuity. They tried to recapture the same feel of riotous action, but while Giffen’s art could match the dynamism of the King of Comics, the series’ uninspired stories sadly remained quite far from the surrealist spark of the original. To be fair, not even the folks at Batman: The Brave and the Bold managed to do justice to Jack Kirby’s imaginative concepts, although they sure came closer.